The presence of extraglandular manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome opens a wide debate in the field of neurology, where the association or similarity with multiple sclerosis and optical neuromyelitis spectrum raises the need for better markers, among which anti-aquaporin 4 antibodies have gained more relevance. Likewise, the technique for measuring these autoantibodies, carried out in serum and in cerebrospinal fluid, is useful for diagnosis and prognosis. The following is a case of Sjögren’s syndrome without sicca symptoms, with unilateral optic neuritis.

La presencia de manifestaciones extraglandulares del síndrome de Sjögren abre un amplio debate en el campo de la neurología, en el cual la asociación o similitud con la esclerosis múltiple y el espectro de la neuromielitis óptica plantea la necesidad de mejores marcadores, dentro de los cuales los anticuerpos contra la acuaporina 4 han ganado mayor relevancia. Así mismo, la técnica para la medición de estos autoanticuerpos, su realización en suero y en líquido cefalorraquídeo son de utilidad para el diagnóstico y el pronóstico. A continuación, se presenta el caso de un síndrome de Sjögren sin sicca que cursó con neuritis óptica unilateral.

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by dry symptoms, autoantibody production, and lymphocytic infiltration of exocrine glands. However, organ involvement different than those related to sicca symptoms, as an extraglandular manifestation of the disease, is generally underestimated.1–3 It has been described that extraglandular manifestations may precede sicca symptoms as the initial manifestation of SS.4,5

On the other hand, the association of SS with other autoimmune diseases (AD) (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, autoimmune thyroid disease, autoimmune hepatitis, and others not so frequent, such as multiple sclerosis) is well known and described for which the term polyautoimmunity has been used to refer to the association of two or more ADs in an individual, which differs from the concept of overlapping syndromes.1,2

We present a case that is part of the current debate on the presence of optic neuritis as an extraglandular manifestation of SS or the association of SS with neuromyelitis optic spectrum (NMOSD).

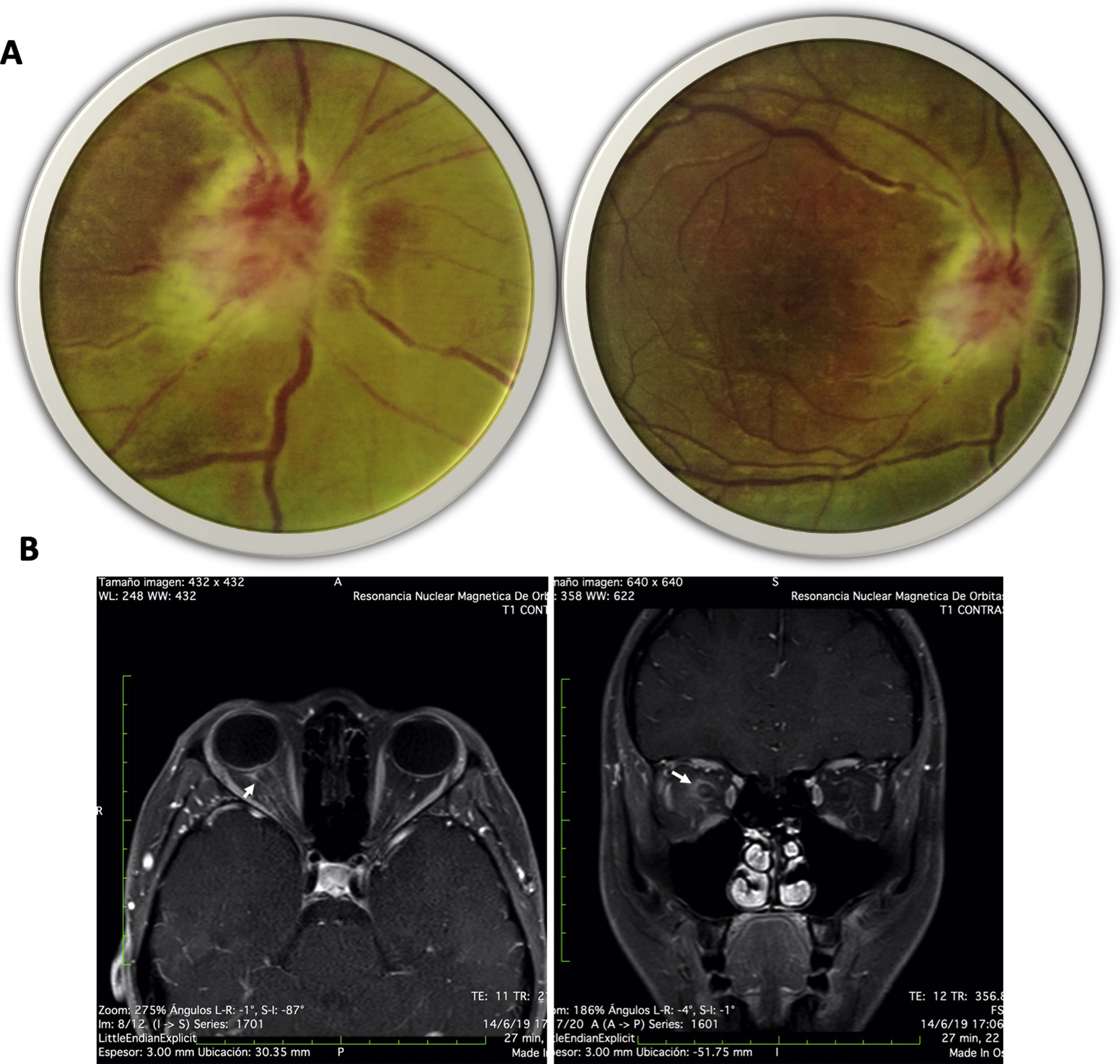

Case presentationA 20-year-old female from a rural area, with no relevant past medical history, presented to the emergency department with a 15-day evolution of stinging pain in the right eye, intensity 10/10, variable, photophobia, and blurred vision. General physical examination was unremarkable. The ophthalmological evaluation revealed Marcus-Gunn pupil in the right eye, counting-fingers visual acuity, with findings in the fundus (Fig. 1A) suggesting right eye (RE) neuroretinitis. Therefore, infectious etiologies (viral, bacterial, and parasitic) were ruled out (Table 1).

(A) Fundus image of the right eye: right optic disc with poorly defined edges, edematous, intumescent characteristics, flame epipapillary microhemorrhages, excavation of 0; there is evidence of effacement of the edges of the disc, areas of periphlebitis affecting the posterior pole and peripapillary retinal edema with some yellowish infiltrates in the posterior pole. (B) Contrasted MRI of orbits, T1 sequence with gadolinium in axial (right) and coronal (left) slices; enhancement of the optic nerve and sheath is evident (arrows).

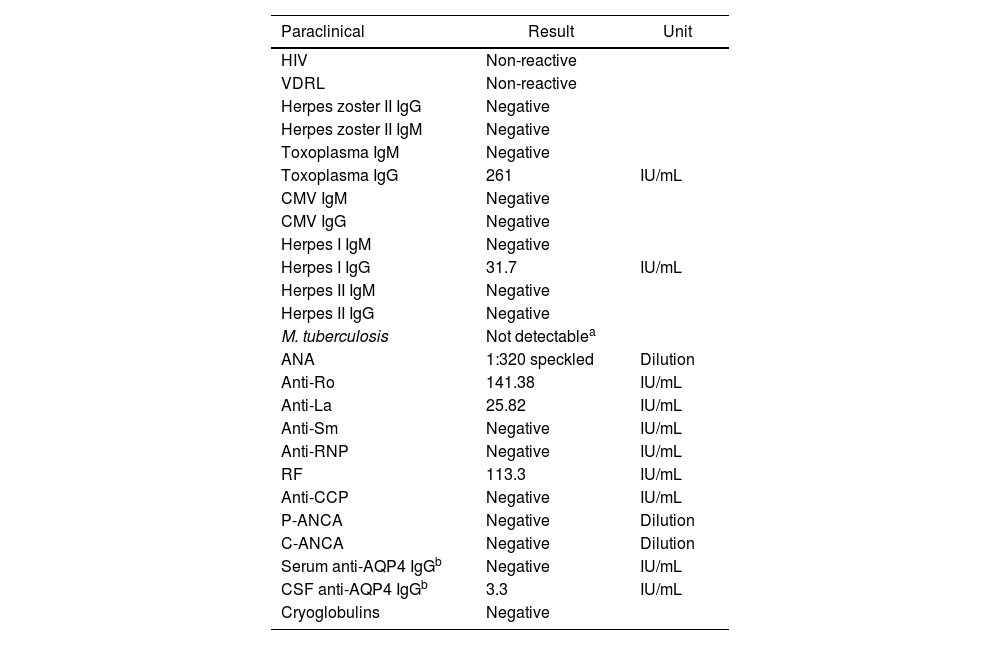

Paraclinical tests of infectious agents and autoimmunity.

| Paraclinical | Result | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| HIV | Non-reactive | |

| VDRL | Non-reactive | |

| Herpes zoster II IgG | Negative | |

| Herpes zoster II IgM | Negative | |

| Toxoplasma IgM | Negative | |

| Toxoplasma IgG | 261 | IU/mL |

| CMV IgM | Negative | |

| CMV IgG | Negative | |

| Herpes I IgM | Negative | |

| Herpes I IgG | 31.7 | IU/mL |

| Herpes II IgM | Negative | |

| Herpes II IgG | Negative | |

| M. tuberculosis | Not detectablea | |

| ANA | 1:320 speckled | Dilution |

| Anti-Ro | 141.38 | IU/mL |

| Anti-La | 25.82 | IU/mL |

| Anti-Sm | Negative | IU/mL |

| Anti-RNP | Negative | IU/mL |

| RF | 113.3 | IU/mL |

| Anti-CCP | Negative | IU/mL |

| P-ANCA | Negative | Dilution |

| C-ANCA | Negative | Dilution |

| Serum anti-AQP4 IgGb | Negative | IU/mL |

| CSF anti-AQP4 IgGb | 3.3 | IU/mL |

| Cryoglobulins | Negative |

AQP4: aquaporin 4; RF: rheumatoid factor.

Neurology concept was requested with suspicion of defects in the optic afferent pathway, confirmed by evoked potentials; contrasted-brain MRI showed enhancement of the optic nerve and sheath (Fig. 1B). Due to suspicion of autoimmune or demyelinating etiology, a lumbar puncture was carried out and reported as normal; cervicothoracic MRI revealed no inflammatory or demyelinating findings, nor autoimmune biomarkers (Table 1).

Since the infectious etiology was reasonably ruled out, the decision was to start methylprednisolone pulses 1&#¿;g IV daily for five days, with prior deworming. Due to the clinical context and the positivity of these biomarkers (Table 1), the possibility of an atypical SS was considered, for which a minor salivary gland biopsy was performed, despite the absence of sicca symptoms, with a positive result (grade-III sialadenitis—Chisholm Mason classification—). Given the lack of improvement in visual acuity and after a multidisciplinary meeting, it was decided to perform four plasmapheresis sessions, with partial improvement in visual acuity (20/200). He was discharged with prednisone at 1&#¿;mg/kg, tapering down to 30&#¿;mg/day. After that, the patient attended a follow-up one month after hospitalization and presented an improvement in visual acuity visual in RE of 20/25 and LE of 20/20, findings of atrophy of the optical nerve, and persistence of the right Marcus-Gunn pupil.

DiscussionSS has a prevalence of 0.12% in people over 18 years, with a major presentation between 65 and 69 years. Of the patients with SS, approximately 15% present with serious complications.6,7 However, as in the current case, it has been described that the age of presentation (under 35 years) has a higher frequency of more severe manifestations (up to 33%).6

The wide variety of manifestations of SS allows to understand it as a systemic disease, in which at least 50% of patients will present them, and not exclusively as an entity with glandular involvement.1,5

Regarding its neurological manifestations, both peripheral and central (CNS) involvement have been described, in which the prevalence in the cohorts even reaches 20%, with an estimate between 2% and 10%, including optic neuritis, hemiparesis, abnormal movements, cerebellar syndromes, transient ischemic attack, and neuromotor syndromes.5,8 Traditionally, the differential diagnosis of the CNS manifestations observes a pattern similar to multiple sclerosis3; however, in the case of NMOSD, there are three hypotheses that the Wingerchuk group has raised, according to which anti-aquaporin4 (AQP4) antibodies play a preponderant role in its relationship with other systemic AEs, such as SS.9,10

The first hypothesis maintains that these two entities do not overlap and that manifestations such as optic neuritis in AQP4-seronegative patients are an expression of AD. The second hypothesis points to the overlap of NMOSD and AD, although the AQP4 would be part of the NMOSD; this hypothesis would have the support of the polyautoimmunity theory. The third hypothesis suggests that AQP4 antibodies are not specific, being perhaps the weakest of the three.10

In the present case, with seronegative serum AQP4 antibodies, two hypotheses are put forward: the first being that optic neuritis corresponds to an extraglandular manifestation of SS, or is part of the group of seronegative NMOSDs; shortly, when new antibodies such as IgG-MOG&#¿;+&#¿;are widely available, it will be possible to improve the diagnosis of the entire NMOSD spectrum, establish a phenotype-based prognosis, and guide a more specific treatment.11 The second hypothesis proposes that AQP4 seronegativity and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) positivity may correspond to a false-positive result since current recommendations promote serum AQP4 measurement through cell-based indirect immunofluorescence assay (CBA); in the current case, it was measured by ELISA. Similarly, the criteria described by Wingerchuk in 2006, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) in 2008, refer to the presence of serum antibodies described by Lennon et al.12 These confer a diagnostic value and a prognostic marker within the entire spectrum of NMOSD, since its serum concentration exceeds that circulating in the CNS and, therefore, the opposite would be discordant.12,13 Likewise, the literature does not identify NMOSD cases with CSF positivity and serum negativity; even research like Kaneko et al.14 shows that this dissociation is not expected.

Consequently, this case opens the doors to the need for greater interaction between neurology and rheumatology teams, considering that as of now, evidence shows that AQP4 antibodies have an essential diagnostic role; the CBA serum technique confers greater sensitivity and specificity to the test. Thus, it could be possible to differentiate whether an optic neuritis clinical picture corresponds to NMOSD or is a neurological manifestation of SS or other systemic ADs.

Ethical responsibilitiesThe authors declare that this article does not contain personal information that would allow the identification of the patient and that consent for the publication of this article is available.

FinancingThe authors declare that they did not receive financial help from third parties for the preparation of this manuscript and that everything was done with their resources.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.