The concept of “risk in healthcare” is relatively new, it emerged in the British epidemiological language at the beginning of the XX Century and is defined by the WHO as the probability of an adverse health outcome, or the presence of a factor that increases that probability. The risk management is defined, in turn, as the process of identifying, analyzing and quantifying the probabilities of losses and side effects that arise from the acts in healthcare, as well as the corresponding preventive, corrective and reductive actions that should be undertaken. The risk management is a structured managerial process which aims to identify the main health risks for the population or the individual. The identified risks are intervened through coordinated strategies that seek to decrease their occurrence

The Colombian Ministry of Health defines as “biological drugs” those drugs derived from living cells or organisms or from their parts. They can be obtained from sources such as tissues or cells, components of human or animal blood (as antitoxins and other type of antibodies, cytokines, growth factors, hormones and coagulation factors), viruses, microorganisms and products derived from them such as toxins. These products are obtained with methods that include (but are not limited to culture of cells of human or animal origin, cultivation and propagation of microorganisms and viruses) processing of human or animal tissues or biological fluids, transgenesis, techniques of recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), and hybridoma techniques. The drugs that result from the latter two methods are called biotechnological drugs.

Starting from the mechanism of action of these drugs, the potential risk of development of infectious diseases was expected. With their use, other side effects have been identified. It is for this reason that it is imperative that all professionals who prescribe biological therapy know the potential risks of their use and how to avoid or reduce them. With this document, the Colombian Association of Rheumatology (Asoreuma) proposes to unify criteria of prescribers and providers regarding the risk management in the use of biological therapy.

An adequate patient selection, counseling and education of patients, caregivers and healthcare personnel are necessary measures for the successful use of this immunosuppressive therapy. A detailed medical history that allows to detect the contraindications of this therapy and the development of follow-up guidelines with their respective implementation are important steps to reduce the risk inherent to the administration of biological agents.1

The objective of these recommendations is to provide rheumatologists and other specialists with tools to make a proper risk management derived from the prescription of the immunosuppressive biological therapy during the treatment of the different autoimmune and inflammatory pathologies.

MethodologyIt was created a group of experts, members of Asoreuma with invitation to medical specialists in cardiology, infectology and pneumology, who carried out a presential and virtual work in groups. At a first meeting were generated the research questions that would be developed in the guidelines, with the support of methodologists experts in evidence-based medicine and development of care guidelines.

Once the working groups and the research questions were defined, the search strategy was developed by the Center for Evaluation of Technologies of the CES University; the search had the advice of Asoreuma.

A systematic search was performed in Pubmed, Cochrane Library Plus, EBSCO, HINARI, IMBIOMED, LILACS, MEDLINE, OVID, Taylor & Francis, for each clinical question of the guide with the key words MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) and DeCS (Descriptors in Health Sciences). Experimental and observational epidemiological studies were included, without restrictions regarding the date of publication; as a limit of language only the articles published in English or Spanish were evaluated. The end date of the search was June of 2013.

The search results were sent to the work teams of Asoreuma, who held 2 meetings of the consensus nominal group, moderated by the methodologist of the CES. The quality of information (quality of evidence) was evaluated at the first meeting and the issues most controversial and of greatest interest for the consensus were decided. The clinical studies identified by the specialists in the different areas were sent to the Center for Evaluation of Technologies of the CES University in order to assess the quality independently.

In the following meetings, doubts about the quality of evidence (agreement among the reviewers for the selection of the studies) were resolved, answers were given to the clinical questions and the grade of the recommendations was established. The review of the full text of the article and the data extraction were performed by the previously established working groups.

The quality of the evidence for observational studies was evaluated by the declaration of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) initiative, the clinical trials were evaluated using the Jadad scale, and the meta-analyses by means of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.

The clinical trials with a score less than 3 in the Jadad scale were not taken into account, as well as the articles that do not adequately inform on the methodology and the results according to the STROBE and the PRISMA statement.

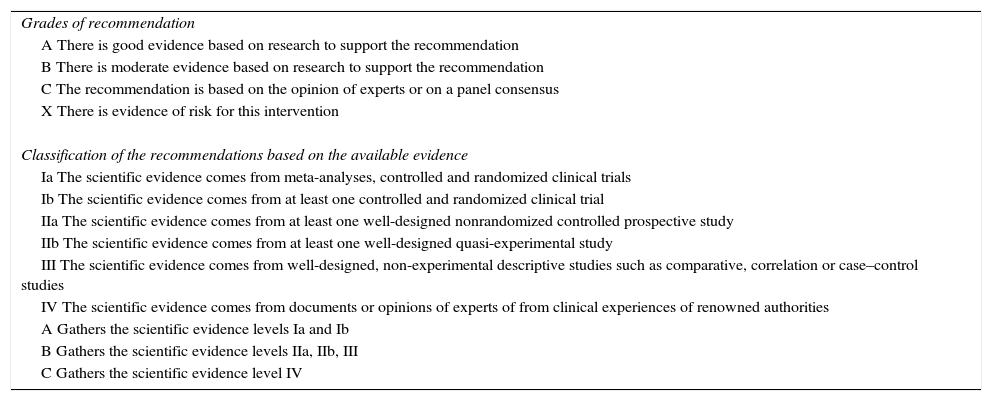

The levels of evidence (LE) and grades of recommendations (GR) are expressed according to the model of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Table 1).

Model of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

| Grades of recommendation |

| A There is good evidence based on research to support the recommendation |

| B There is moderate evidence based on research to support the recommendation |

| C The recommendation is based on the opinion of experts or on a panel consensus |

| X There is evidence of risk for this intervention |

| Classification of the recommendations based on the available evidence |

| Ia The scientific evidence comes from meta-analyses, controlled and randomized clinical trials |

| Ib The scientific evidence comes from at least one controlled and randomized clinical trial |

| IIa The scientific evidence comes from at least one well-designed nonrandomized controlled prospective study |

| IIb The scientific evidence comes from at least one well-designed quasi-experimental study |

| III The scientific evidence comes from well-designed, non-experimental descriptive studies such as comparative, correlation or case–control studies |

| IV The scientific evidence comes from documents or opinions of experts of from clinical experiences of renowned authorities |

| A Gathers the scientific evidence levels Ia and Ib |

| B Gathers the scientific evidence levels IIa, IIb, III |

| C Gathers the scientific evidence level IV |

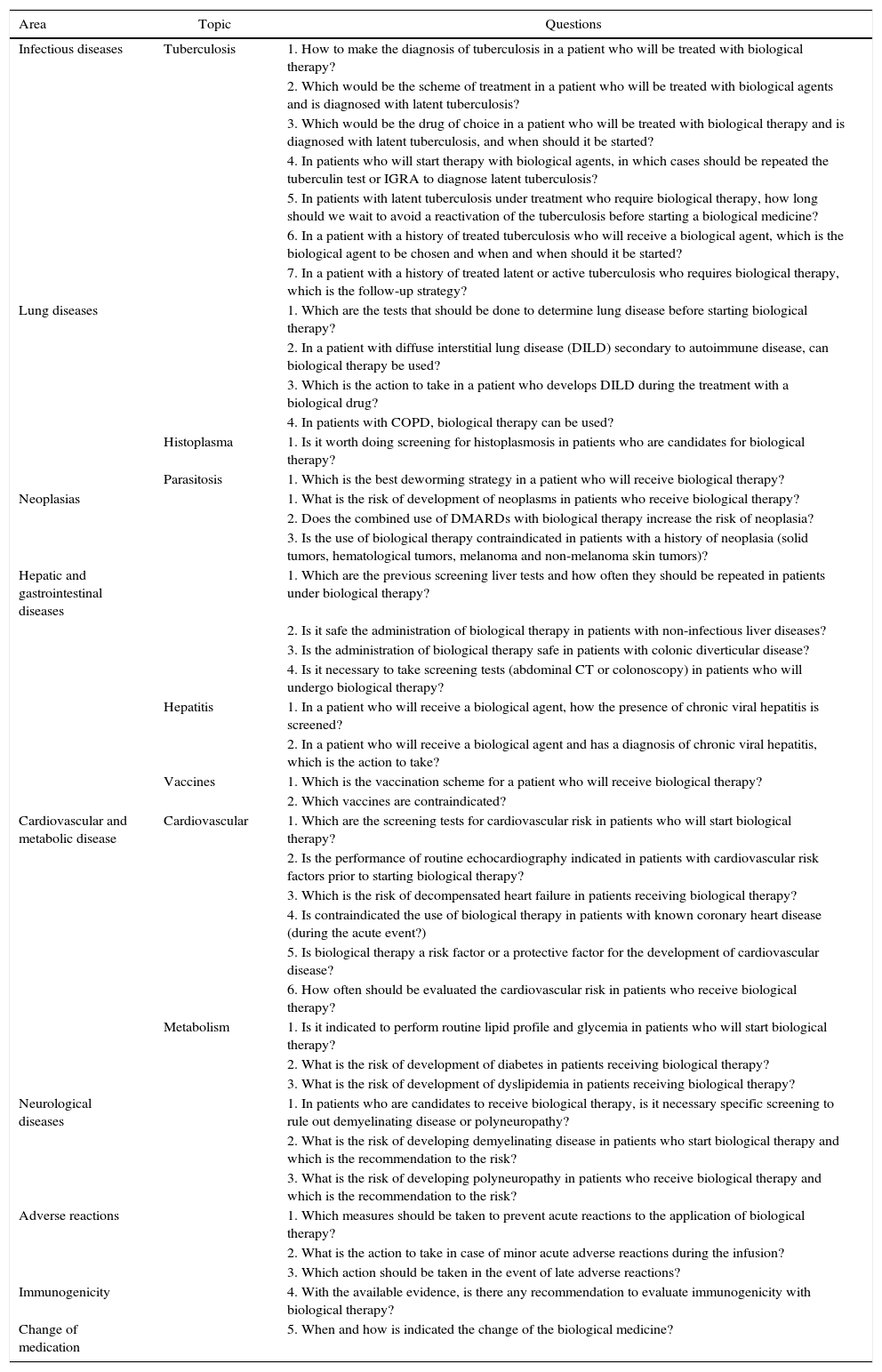

Table 2 lists the established topics and questions that were subsequently developed by the experts.

Questions of the expert consensus.

| Area | Topic | Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Infectious diseases | Tuberculosis | 1. How to make the diagnosis of tuberculosis in a patient who will be treated with biological therapy? |

| 2. Which would be the scheme of treatment in a patient who will be treated with biological agents and is diagnosed with latent tuberculosis? | ||

| 3. Which would be the drug of choice in a patient who will be treated with biological therapy and is diagnosed with latent tuberculosis, and when should it be started? | ||

| 4. In patients who will start therapy with biological agents, in which cases should be repeated the tuberculin test or IGRA to diagnose latent tuberculosis? | ||

| 5. In patients with latent tuberculosis under treatment who require biological therapy, how long should we wait to avoid a reactivation of the tuberculosis before starting a biological medicine? | ||

| 6. In a patient with a history of treated tuberculosis who will receive a biological agent, which is the biological agent to be chosen and when and when should it be started? | ||

| 7. In a patient with a history of treated latent or active tuberculosis who requires biological therapy, which is the follow-up strategy? | ||

| Lung diseases | 1. Which are the tests that should be done to determine lung disease before starting biological therapy? | |

| 2. In a patient with diffuse interstitial lung disease (DILD) secondary to autoimmune disease, can biological therapy be used? | ||

| 3. Which is the action to take in a patient who develops DILD during the treatment with a biological drug? | ||

| 4. In patients with COPD, biological therapy can be used? | ||

| Histoplasma | 1. Is it worth doing screening for histoplasmosis in patients who are candidates for biological therapy? | |

| Parasitosis | 1. Which is the best deworming strategy in a patient who will receive biological therapy? | |

| Neoplasias | 1. What is the risk of development of neoplasms in patients who receive biological therapy? | |

| 2. Does the combined use of DMARDs with biological therapy increase the risk of neoplasia? | ||

| 3. Is the use of biological therapy contraindicated in patients with a history of neoplasia (solid tumors, hematological tumors, melanoma and non-melanoma skin tumors)? | ||

| Hepatic and gastrointestinal diseases | 1. Which are the previous screening liver tests and how often they should be repeated in patients under biological therapy? | |

| 2. Is it safe the administration of biological therapy in patients with non-infectious liver diseases? | ||

| 3. Is the administration of biological therapy safe in patients with colonic diverticular disease? | ||

| 4. Is it necessary to take screening tests (abdominal CT or colonoscopy) in patients who will undergo biological therapy? | ||

| Hepatitis | 1. In a patient who will receive a biological agent, how the presence of chronic viral hepatitis is screened? | |

| 2. In a patient who will receive a biological agent and has a diagnosis of chronic viral hepatitis, which is the action to take? | ||

| Vaccines | 1. Which is the vaccination scheme for a patient who will receive biological therapy? | |

| 2. Which vaccines are contraindicated? | ||

| Cardiovascular and metabolic disease | Cardiovascular | 1. Which are the screening tests for cardiovascular risk in patients who will start biological therapy? |

| 2. Is the performance of routine echocardiography indicated in patients with cardiovascular risk factors prior to starting biological therapy? | ||

| 3. Which is the risk of decompensated heart failure in patients receiving biological therapy? | ||

| 4. Is contraindicated the use of biological therapy in patients with known coronary heart disease (during the acute event?) | ||

| 5. Is biological therapy a risk factor or a protective factor for the development of cardiovascular disease? | ||

| 6. How often should be evaluated the cardiovascular risk in patients who receive biological therapy? | ||

| Metabolism | 1. Is it indicated to perform routine lipid profile and glycemia in patients who will start biological therapy? | |

| 2. What is the risk of development of diabetes in patients receiving biological therapy? | ||

| 3. What is the risk of development of dyslipidemia in patients receiving biological therapy? | ||

| Neurological diseases | 1. In patients who are candidates to receive biological therapy, is it necessary specific screening to rule out demyelinating disease or polyneuropathy? | |

| 2. What is the risk of developing demyelinating disease in patients who start biological therapy and which is the recommendation to the risk? | ||

| 3. What is the risk of developing polyneuropathy in patients who receive biological therapy and which is the recommendation to the risk? | ||

| Adverse reactions | 1. Which measures should be taken to prevent acute reactions to the application of biological therapy? | |

| 2. What is the action to take in case of minor acute adverse reactions during the infusion? | ||

| 3. Which action should be taken in the event of late adverse reactions? | ||

| Immunogenicity | 4. With the available evidence, is there any recommendation to evaluate immunogenicity with biological therapy? | |

| Change of medication | 5. When and how is indicated the change of the biological medicine? |

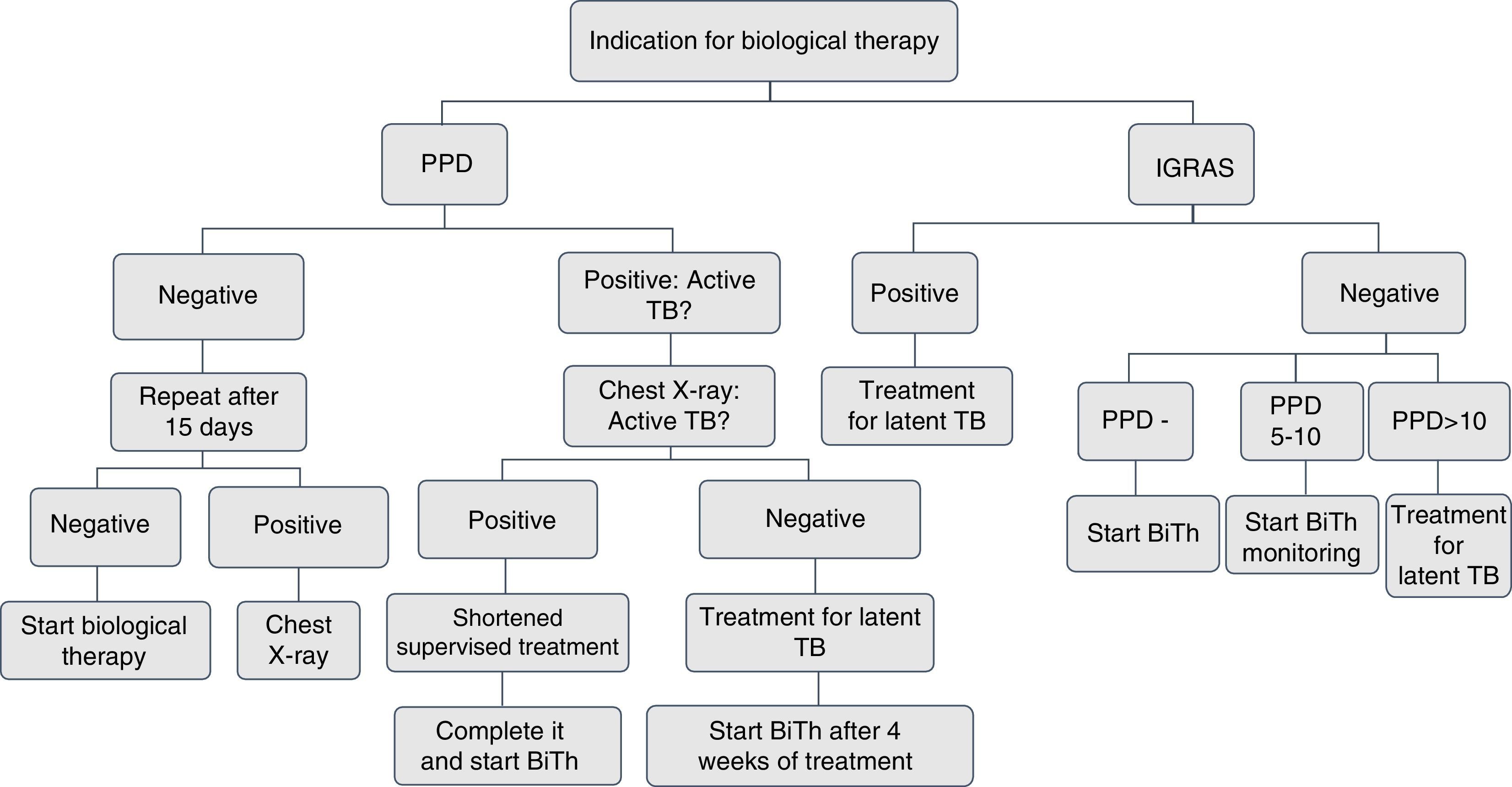

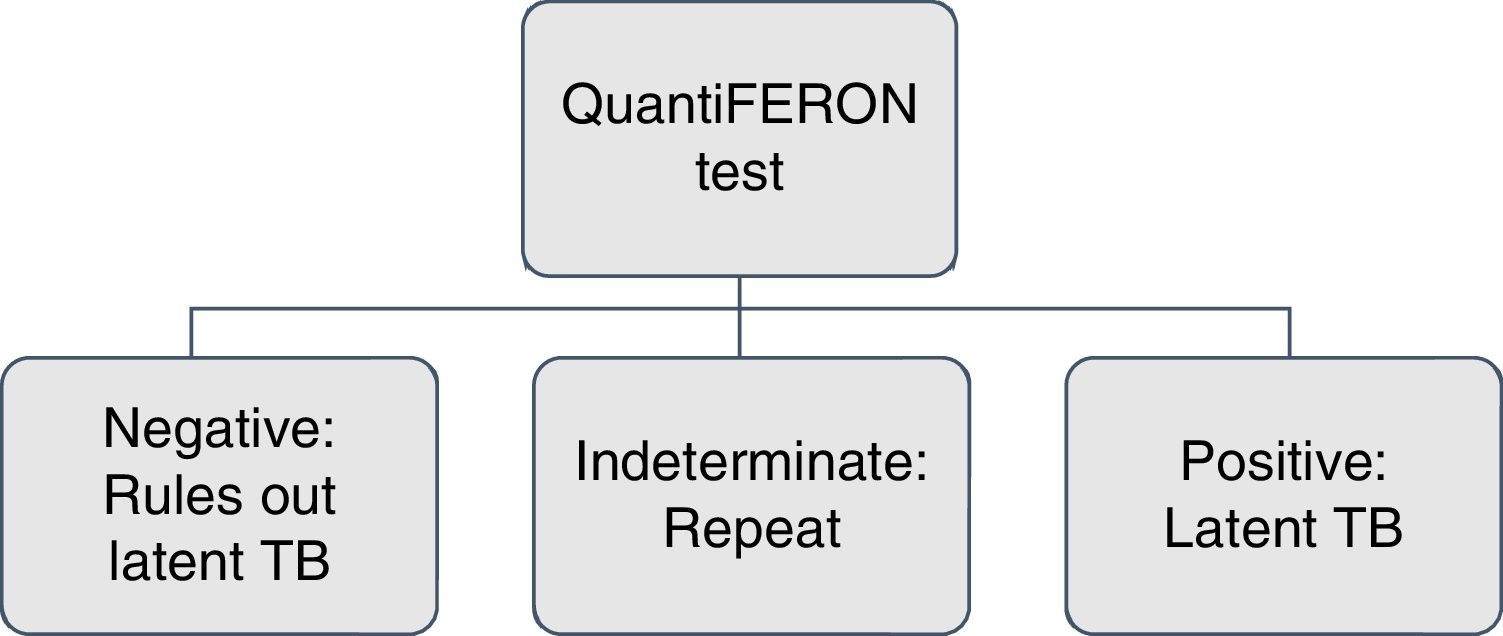

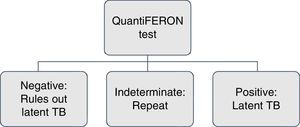

Screening for latent tuberculosis with a tuberculin skin test or interferon-γ release assays (IGRA) and a chest X-ray must be carried out to all patients for whom immunosuppressive biological therapy is prescribed. The tuberculin skin test (unipuncture 5U) or IGRA (QuantiFERON-TB Gold In Tube or TB spot) have equal sensitivity for screening.2,3 An induration ≥5mm is considered a positive test.

The negative tuberculin skin test TST (<5mm) should be repeated within 1 and 3 weeks, when the patient has risk factors for active tuberculosis, such as confinement in overcrowded conditions, contact with patients with active tuberculosis or healthcare workers.3,4

Every patient must have a chest radiograph at the beginning of the biological therapy. If the result of the TST is positive, the radiograph should be evaluated with the pneumologist in search of active tuberculosis. Sputum smears should be taken to establish the presence of acid-fast bacilli in patients with active respiratory symptoms.5–7 The use of IGRA is indicated in patients with a positive tuberculin test, with suspected false positive due to the conditions of the patient, the site of application or the quality of the reading.7,8

If the history of BCG vaccination of the patient is shorter than 3 years, use IGRA.9,10

In patients with a history of liver damage of toxic or infectious origin, consumption of multiple drugs and high risk of complications; with the use of isoniazid are recommended the IGRAs because of their greater specificity11 (Figs. 1 and 2).

In patients who have difficulties to get the tuberculin test, for geographical and displacement reasons, IGRAs can be used, since they have the same sensitivity.11,12

The use of the Online TST/IGRA (http://tstin3d.com/en/calc.html) calculator13,14 is recommended to establish the risk; if it exceeds the 0.02% annual, treatment for latent tuberculosis should be considered.

In case that neither tuberculin nor IGRAs are available, active tuberculosis must be ruled out with a chest X-ray, and if there are symptoms, with sputum smears. It should be performed a clinical and educational follow-up of the patient, the family and the caregivers on the signs and symptoms that indicate the possibility of active tuberculosis.13,15,16

2. Which would be the scheme of treatment in a patient who will be treated with biological agents and is diagnosed with latent tuberculosis?Recommendation: LE: 1; GR: AThe working group considered that once the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis is established, treatment should be started before the beginning of the biological medicines. As first-line treatment is recommended isoniazid (INH) 5mg/kg/day in a dose not higher than 300mg/day plus pyridoxine 50mg/day for 9 months.17–20

In case of intolerance to INH, it should be given rifampicin 10mg/kg/day up to a maximum of 600mg/day, for 4 months.19,20 Once treatment is started, liver function tests should be performed periodically and the patient must be addressed to the group of follow-up of tuberculosis cases.20

3. Which would be the drug of choice in a patient who will be treated with biological therapy and is diagnosed with latent tuberculosis, and when it should be started?Recommendation: LE, 5; GR, D21In patients with a diagnosis of latent tuberculosis, the biological therapy can be initiated once the first 4 weeks of the prescribed treatment are completed.22,23

There is no evidence against the initiation of either of the biological therapies once the patient has completed at least one month of treatment for latent tuberculosis and finished the supervised shortened treatment for active tuberculosis.21,23,24

4. In patients who will start therapy with biological agents, in which cases should be repeated the tuberculin test or IGRA to diagnose latent tuberculosis?Recommendation LE 2b; GR B16The initial tuberculin test that results <5mm should be repeated after 3 weeks when the patient has risk factors for active tuberculosis, such as confinement in overcrowded conditions, contact with patients with active tuberculosis, are healthcare workers or are in a state of immunosuppression.25

Perform IGRA again if the patient has a high degree of immunosuppression and the result is uninterpretable or indeterminate.17,26

The IGRA test should be repeated when the patient has risk factors such as contact with individuals with active tuberculosis, is a healthcare worker, or lives in overcrowded conditions.26,27

The tuberculin tests or the IGRAs must be repeated annually in patients under treatment with biological therapy who have negative baseline tests and exhibit the risk factors described above.27,28

If the patient has a history of prior complete treatment for active or latent tuberculosis, these tests should not be done again.27

5. In patients with latent tuberculosis under treatment who require biological therapy, how long should we wait to avoid a reactivation of the tuberculosis before starting a biological medicine?Recommendation: LE, 5; GR, DThe patient with latent tuberculosis diagnosed prior to the beginning of the biological drug must receive therapy with isoniazid at 5mg/kg, maximum 300mg/day, plus pyridoxine 50mg/day, at least for one month before starting biological therapy, with a schedule of 9 months thereof.28–31

In the case of a patient intolerant to isoniazid, the therapy should be done with rifampicin 10mg/kg/day, up to a maximum of 600mg/day.19,20

6. In a patient with a history of treated tuberculosis and who needs biological therapy, which is the molecule that should be chosen and when is the time to start it?Recommendation: LE 4; GR CIn patients with a history of active or latent tuberculosis properly treated, biological therapy can be started, with a strict clinical follow-up of the patient.22,32

The data from post-marketing surveillance records have shown and increased risk of tuberculosis in patients receiving anti-TNF, with a 3–4 times higher risk associated with infliximab and adalimumab than with etanercept.33

7. In a patient with a history of treated latent or active tuberculosis who requires biological therapy, which is the follow-up strategy?Recommendation: LE 5; GR DIn patients with a history of latent or active tuberculosis adequately treated, who require biological therapy, is not necessary to perform new tuberculin tests, or prophylaxis.1

The clinical follow-up of the patient and the education on warning symptoms of active tuberculosis is fundamental.1,3,13

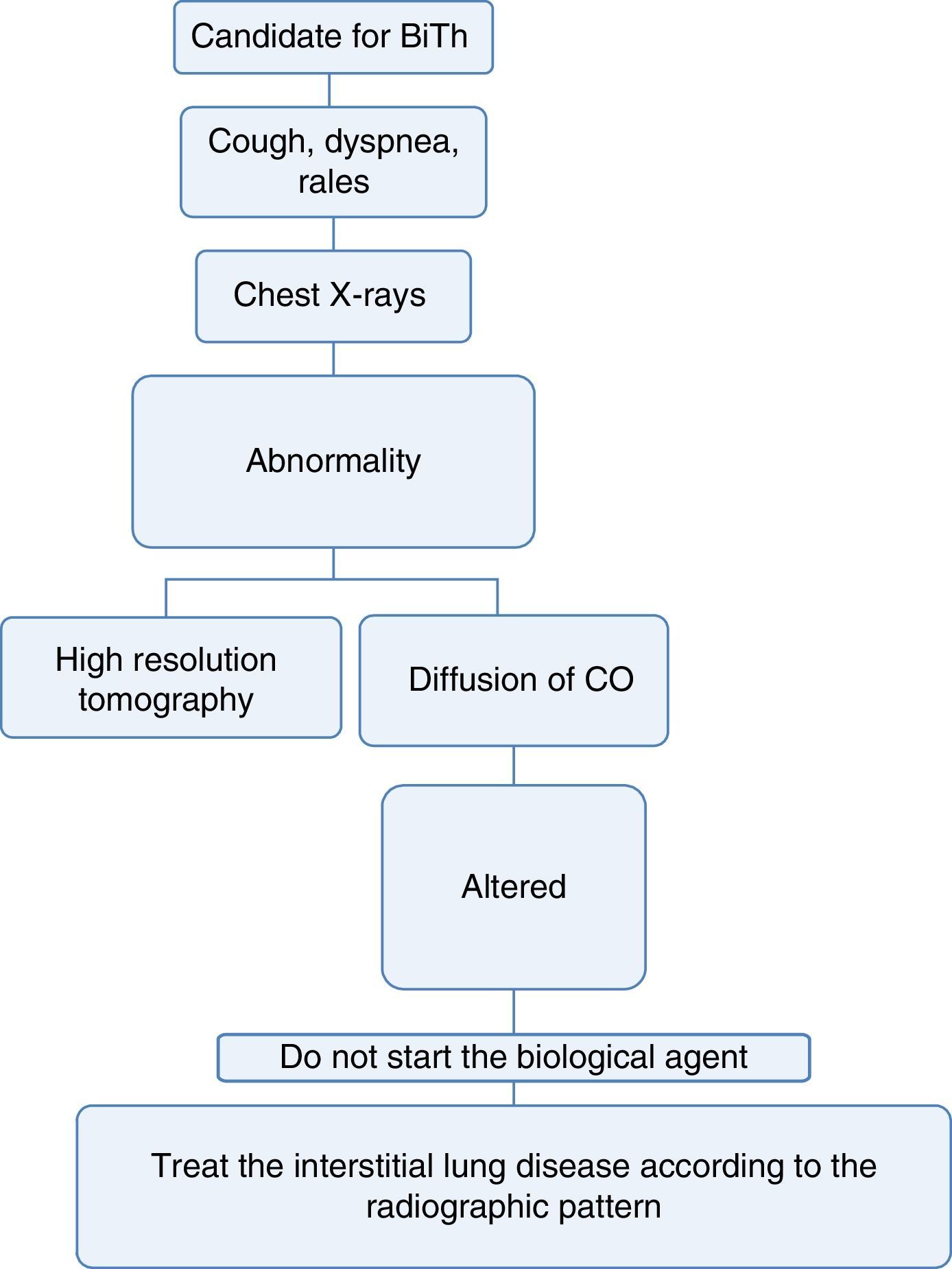

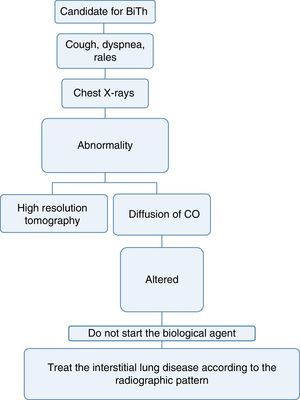

Pneumology1. Which are the tests that should be done to determine lung disease before starting biological therapy?Recommendation: LE: 4; GR: CEvery patient considered a candidate for starting biological therapy must have:

- a)

A complete medical record that includes history of exposure to the smoke from biomass combustion, active or passive smoking, exposure to toxic fumes or any environmental or occupational respiratory exposure of risk for the development of interstitial lung disease.34

- b)

A complete physical examination focused on the detection of cough, dyspnea or any other abnormality at pulmonary auscultation.34,35

- c)

A chest X-ray in posteroanterior and lateral projections, ideally, in order to be able to compare it with the radiograph taken at the time of diagnosis of the disease.36

- d)

If the patient has a disease that may, among its manifestations, generate diffuse interstitial lung disease (DILD) or if the conventional radiography suggests alterations, a diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) test and a high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest could be performed. The latter increases the diagnostic sensitivity for DILD by up to 60% and allows to approach the pattern of interstitial involvement to define the therapy36–38 (Fig. 3).

With the information available in the literature, the use of biological therapy is not recommended in patients with diffuse lung disease, since these drugs may exacerbate the lung involvement.39

The drugs with a mechanism of action of anti-interleukins type have demonstrated to exacerbate the underlying interstitial lung disease and they also induce this pathology in patients without a previous history.40,41

Mortality increases by up to 35% in patients with autoimmune or inflammatory disease with associated interstitial lung disease.22,42

The evidence is contradictory with abatacept and no recommendations can be made.43

The therapy with an anti-CD20 mechanism of action, especially rituximab, also exacerbates the interstitial lung disease. There have been demonstrated cases of acute and subacute hypoxemic organizing pneumonia and macronodular organizing pneumonia.44,45

3. Which is the action to take in a patient who develops diffuse interstitial lung disease during the treatment with a biological drug?Recommendation: LE: 4; GR: CIn patients who develop interstitial lung disease during the treatment with biological therapy, the action to take must be the discontinuation of the drug and the initiation of the appropriate therapy according to the severity of the disease.46,47

4. In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, biological therapy can be used?Recommendation: LE: 4; GR: CIn patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), biological therapy can be used provided that lung infection, including active tuberculosis, has been previously ruled out.48–50

There are data regarding that abatacept might increase the risk of lung infection, which would increase exacerbations; however, the existing evidence do not allow to draw statistically significant conclusions.51

5. It should be done screening for histoplasmosis in patients who are candidates for biological therapy?Recommendation: LE: 4; GR: CThis infection should be suspected in patients who are in endemic areas for Histoplasma capsulatum.52,53

Parasitosis1. Which is the best deworming strategy in a patient who will receive biological therapy?Recommendation: LE: 4; GR: CIn all patients in whom biological therapy will be started is recommended prophylaxis with ivermectin at doses of 200μg/kg/day (one drop per kilogram of body weight) for 2 days, this dose should be repeated 2 weeks later.54–56

A therapeutic option covered by the Compulsory Plan of Health (POS) is albendazole 400mg/day, for 3 days.56

Malignancy1. What is the risk of development of neoplasms in patients who receive biological therapy?Recommendation: LE: 1; GR: AThere is no evidence of increased risk of solid tumors in patients under biological therapy.57–59

2. Is there an increased risk of basal cell carcinoma in patients with the use of anti-TNF drugs?Recommendation: LE: 1; GR: ACurrently there is no evidence of significant increased risk for lymphoma in patients with RA using biological therapy compared with patients treated with DMARD and with the historical cohorts of RA.60–62

3. Does the combined use of DMARD with biological therapy increase the risk of neoplasia?Recommendation: LE: 1; GR: AThe evaluated evidence did not show that the groups of combined therapy of DMARD with biological therapy have a higher risk of neoplasia.58

4. Is the use of biological therapy contraindicated in patients with a history of neoplasia (solid tumors, hematological tumors, melanoma and non-melanoma skin tumors)?Recommendation: LE: 4, GR: C63In patients with a history of lymphoproliferative neoplasms, the use of biological therapy is not recommended, except rituximab.27

5. Is feasible its use 5 year after diagnosis of the neoplasia and with no evidence of recurerence?27Recommendation: LE: 4; GR: CIn the absence of sufficient data on recurrent cancer, patients with a previous or a new cancer should be informed about the possible risk of new or recurrent cancers during the treatment with anti-TNF or with some of the DMARDs. It is recommended to evaluate with the oncologist the risks and benefits of starting biological therapy for RA. Its use is feasible 5 years after diagnosis of the neoplasia and without evidence of recurrence.27,57,58,58a

Non-infectious gastrointestinal and liver disease1. Which are the previous screening liver tests and how often they should be repeated in patients under biological therapy?Recommendation: LE: 4; GR: CThere is no formal recommendation for requesting liver function tests (SGOT, SGPT, alkaline phosphatase, GGT) prior to starting biological therapy. However, there have been described cases of liver disease induced by anti-TNF, and for this reason is recommended to carry out these tests previously.64–66

In all patients who will start therapy, past or current infection with HBV or HCV should be ruled out by carrying out the following tests: HBsAg, HBsAb, HBcAb and anti-HCV. If there is evidence of current infection with HBV, a viral load test should be performed.27,67

2. Is it safe the administration of biological therapy in patients with non-infectious liver diseases?Recommendation: LE: 4; GR: CThe available evidence is scarce; there are reports of cases that do not allow to make a clear recommendation for its use.

The anti-TNF therapy has not been evaluated for the treatment of patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). However, there are reports of patients with NASH who have had rapid normalization of liver biochemical tests during the treatment for RA with adalimumab. Further studies are required to evaluate the role of anti-TNFs in patients with NASH.68–70

The anti-TNF have demonstrated acceptable safety in the short term, and hepatotoxicity may occur in susceptible patients; regular monitoring of the levels of aminotransferases should be ensured in patients treated with these agents.

3. Is the administration of biological therapy safe in patients with colonic diverticular disease? In particular, is there an increased risk of perforation or diverticulitis?Recommendation LE: 4; GR: CDuring the treatment with biological medicines the presence of intestinal perforation is uncommon, but it constitutes a serious adverse effect especially in patients with RA. The risk is greater in patients with concomitant treatment with NSAIDs or glucocorticoids (GCs) (HR: 4.7) and diverticular disease. NSAIDs and GCs have been associated with severe complications of diverticular disease. Eighteen cases of lower gastrointestinal perforation have been documented in patients with RA treated with tocilizumab in clinical trials. In phase III studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of tocilizumab it has been found a rate of gastrointestinal perforation of 1.9 per 1.000 patients (1.3 for anti-TNF, GCs: 3.9). The majority of these patients were receiving NSAIDs or GCs.71–73

There is no contraindication for the use of biological therapy in patients with diverticular disease; however, caution is suggested with its use.74

4. Is it necessary to take screening tests (abdominal CT or colonoscopy) in patients who will undergo biological therapy?Recommendation: LE: 4; GR: CThe risk of diverticular perforation may be slightly higher in patients treated with tocilizumab, compared with conventional DMARDs or anti-TNF agents, but lower than with GCs. The mechanism of action of IL-6 antagonism in the pathophysiology of diverticular perforation is not known.72

Caution should be taken with the use of immunosuppressive medication in patients with symptomatic diverticular disease. It is important to perform additional studies in patients with lower gastrointestinal symptoms who receive biological agents.72

Infectious liver disease1. In a patient who will receive a biological agent, how the presence of chronic viral hepatitis is screened?Recommendation: LE: 4; GR: CIn the initial screening process should be requested: HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; anti-HBc: anti-core antibodies; anti-HBs: anti-HBs antibodies and total antibodies to hepatitis C.

Refer the patients with chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection to Infectology and Hepatology in order to start treatment.

Patients who are negative for the antibody against the hepatitis B surface antigen must be vaccinated following the immunization schedule recommended for the general population, always doing it prior to the start of the therapy in order to optimize the formation of protective antibodies.

There are series of cases of patients with autoimmune diseases treated with biological therapy that show that in those patients with chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C, the disease can be reactivated after immunosuppression.75–82

2. Which is the drug of choice for patients with hepatitis B or C to whom biological therapy should be started?Recommendation: LE: A; GR: CChronic hepatitis B and C can be serious comorbidities in patients with rheumatic diseases. Reactivation of hepatitis B is frequent in infected patients receiving therapy with anti-TNF or rituximab who are not provided with an adequate antiviral prophylaxis.

Oral antiviral therapy can prevent the reactivation of the hepatitis B virus and is recommended for all infected patients who receive high risk immunosuppressive therapy.

Patients with a history of past infection by hepatitis B should be carefully assessed and monitored during therapy, especially those who receive B cells depleting drugs.

In patients with rheumatic disease with chronic hepatitis C, the biological therapy with anti-TNF or rituximab appears to be safe.83–88

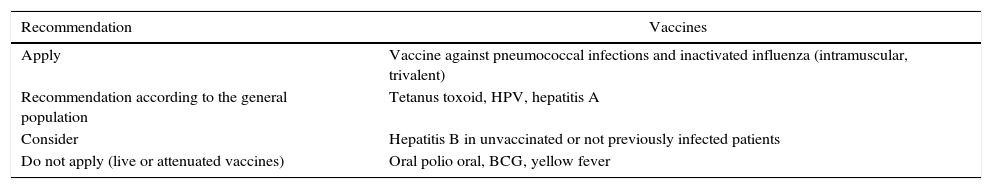

Vaccination1. Which vaccines should be recommended before starting a biological agent?Recommendation: LE: 4; GR: CIt is recommended to review the scheme of vaccination in patients with autoimmune disease and to complete it following the recommendations that apply for non-positive HIV immunosuppressed patients. The use of live or attenuated vaccines is contraindicated (Table 3). The recommendations of the Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Vaccination of the Adult and the Adolescent in Colombia 201289 and the recommended vaccination scheme for adults in the United States89–93 are followed (http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/adult/adult-schedule).

Recommendations for application of vaccines.

| Recommendation | Vaccines |

|---|---|

| Apply | Vaccine against pneumococcal infections and inactivated influenza (intramuscular, trivalent) |

| Recommendation according to the general population | Tetanus toxoid, HPV, hepatitis A |

| Consider | Hepatitis B in unvaccinated or not previously infected patients |

| Do not apply (live or attenuated vaccines) | Oral polio oral, BCG, yellow fever |

In general, an annual evaluation of cardiovascular risk is recommended for all patients who have inflammatory arthritis, which can be spaced to every 2 years in patients at low risk; likewise, each time when a change in treatment is determined, including biological therapy, this risk must be reevaluated.94–97

2. Is the performance of routine echocardiography indicated in patients with cardiovascular risk factors prior to starting biological therapy?There is not sufficient evidence to make recommendations. The published guidelines for cardiovascular risk assessment do not include routine echocardiographic evaluation.94,98–100

3. In patients receiving biological therapy, what is the risk of developing cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease, chronic occlusive arterial disease)?Recommendation: LE: 2b; GR: CThe use of biological therapy has demonstrated to decrease the risk of developing cardiovascular disease. It reduces the use of steroids and NSAIDs, which are recognized risk factors.101–103

The inhibition of TNF-alpha would improve the endothelial function and would decrease the progression of endothelial dysfunction105; apparently, based on cohort studies, it has been demonstrated a trend toward the reduction of the risk for all events, although more evidence is needed in this regard.104,106–108

4. Which is the risk of decompensated heart failure in patients receiving biological therapy?Although the risk of developing heart failure with anti-TNF has not been accurately established, there is sufficient evidence to indicate that its use adversely affects patients with moderate to severe heart failure.109–128

5. Does the presence of diabetes increase the risk of infection in patients who start biological therapy?Diabetes is an independent risk factor for infection in patients with inflammatory disease who use immunomodulatory therapy. However, it is controversial whether there is an increase in the risk of infections with the addition of anti-TNF therapy.129–134

6. What is the risk of development of dyslipidemia in patients receiving biological therapy?RA is associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, due not only to the traditional cardiovascular risk factors, but also to a chronic inflammatory state. However, the lipid levels in patients with RA are different from those observed in the general population at risk for cardiovascular pathologies, where there is evidence of a positive relationship between the disease and high cholesterol levels. The untreated patients with active RA show paradoxically low lipid levels in relation to their frequency of cardiovascular disease.

Patients with RA who receive treatment with disease-modifying drugs, biological and synthetic, experience a reduction in inflammation despite increased levels of LDL cholesterol. There is a reduction in the levels of CRP that correlates with increases in the apoA1 and improvements in the HDL cholesterol efflux capacity.135–159

7. How frequently should be evaluated the cardiovascular risk in patients who receive biological therapy?Recommendation: LE: 4; GR: CAn annual evaluation of cardiovascular risk is recommended for all patients with inflammatory arthritis, which can be spaced to every 2 years in patients at low risk; likewise, each time when a change in treatment is determined, including biological therapy, this risk must be reevaluated.94,111,120,149,160–177

8. Which is the most recommended tool for this evaluation?Publications suggest the evaluation of the cardiovascular risk starting from the calculation tool(s) used in each country. If there is not a clear recommendation, it is suggested the use of standardized risk indexes, such as the Framigham score or the SCORE index.178–187

Immunogenicity1. With the available evidence, is there any recommendation for evaluating immunogenicity with biological therapy (monoclonal antibodies, chimeric antibodies)?There is no evidence that supports a recommendation for evaluating the presence of anti-drug antibodies (ADA) in patients under treatment with biological therapy. However, it has been described the presence of these antibodies in different types of therapies. Their frequency decreases with the concomitant administration of immunomodulators.

So far there are not studies that have evaluated the cost-effectiveness of the therapy guided by the determination of drug levels or presence of antibodies, although there is evidence of the association of these antibodies with secondary failure of this type of therapies (LE: 4; GR: C).

The identification of ADA is useful in patients with loss of effectiveness of the drug; if they are positive, possibly there will be no response to the increase in the dose (LE: 4; GR: C).188–191

Neurological1. In patients who are candidates to receive biological therapy, is it necessary screening to rule out demyelinating disease or polyneuropathy?Recommendation: LE 3; GR BAnti-TNF therapy should not be given when there is a clear history of multiple sclerosis, and it should be used with caution in patients with other demyelinating diseases. Anti-TNF therapy must be discontinued in case of a clinical picture suggestive of demyelinating disease.192–196

Adverse reactions1. Which measures should be taken to prevent acute reactions to the application of biological therapy?Recommendation: LE: 4; GR: CRegarding subcutaneous medications, as well as humanized monoclonal antibodies or fusion molecules for intravenous application, no premedication is recommended. With regard to infliximab and rituximab, chimeric molecules, is recommended premedication with glucocorticoids, acetaminophen and antihistamines.197–201

2. What is the action to take in case of minor acute adverse reactions (fever, rash, symptoms of cold, such as malaise or myalgia)?Recommendation: LE: 4; GR: CAs a first step, the medication should be discontinued and should be given treatment with antihistamines and glucocorticoids. According to the symptoms, analgesics and antipyretics (acetaminophen) may be administered. Once the adverse reaction is controlled, the application can be restarted. In the case of rituximab, the acute reactions occurred more frequently in the first application than in the subsequent (29% vs. 8%). Therefore, a minor acute adverse reaction during the first application not necessarily contraindicates the second application.197,202,203

Late adverse reactions1. Which action would be taken in the event of late adverse reactions?RecommendationThe injection site reactions have been described mainly with subcutaneous compounds; they are usually mild or moderate and should not necessarily lead to the discontinuation of the medication, since they often resolve spontaneously during subsequent applications.204 The local or systemic treatment of these lesions will be done at the discretion of the treating physician (LE: 4; GR: C).

Exacerbation of psoriasis: discontinue the anti-TNF drug and treat the lesions by dermatology205 (LE: 4; GR: C).

The use of a different anti-TNF may be considered according to the judgment of the treating physician (LE: 4; GR: C).

The psoriasiform lesions (generally related to anti-TNF) should be evaluated by dermatology. According to the severity of the skin lesions and the response to treatment, it can be considered to continue the same treatment or reinitiate it if it has been discontinued. The use of a different anti-TNF may be considered according to the judgment of the treating physician206,207 (LE: 4, GR: C).

Regarding the infectious skin complications such as ringworm, herpes simplex infection and acute staphylococcal infection, specific treatment should be indicated and they do not necessarily imply the discontinuation of treatment (LE: 4; GR: C).208–213

Administration guidelines1. Which are the minimum requirements for the administration of biological drugs for the first time and during their maintenance in relation to clinical, paraclinical and administrative aspects in rheumatic diseases?RecommendationThe drugs for intravenous application should be administered in centers that comply with the habilitation standards of the respective regulatory body. The healthcare center must have the supervision of a rheumatologist (LE: 4, GR: C).

For the application of biological drugs the following recommendations should be taken into account.

- •

Requirements for starting treatment (SER AR Guidelines):

- -

Rule out pregnancy, infection (including tuberculosis), cancer, heart failure, cytopenias, demyelinating disease or other relevant comorbidity.

- -

Perform the following laboratory tests: complete blood count, liver profile, renal function, urinalysis, markers of hepatitis B and C, chest X-ray, PPD. A lipid profile is recommended before starting tocilizumab.

- -

Vaccination according to the recommendation established in this guide. Deworming (LE: 4; GR: C).

- -

- •

During treatment:

- -

Monitoring the occurrence of infections, optic neuritis (demyelinating diseases), cancer, heart failure.

- -

Recommended follow-up tests: CBC, liver function, renal function, urinalysis, markers of inflammation.

- -

Hygiene recommendations: avoid raw foods, wash properly fruits and vegetables (LE: 4; GR: C).

- -

- •

Indications for discontinuing:

- -

Infection, cancer, demyelinating disease, optic neuritis, severe cytopenia. Serious events related to the drug, major scheduled surgery, pregnancy (LE: 4, GR: C).

- -

There is no recommendation in this regard. Records do not speak of washout periods.214–220

Surgery1. When should be discontinued the biological therapy before a surgical procedure and when should be restarted?Recommendation: LE 4; GR CIn patients who are receiving anti-TNF therapy a risk-benefit balance should be made to discontinue the drug before a major scheduled surgery (risk of infection vs. risk of reactivation of the disease). The drug should be discontinued between 3 and 5 half-lives before the procedure and restarted after the risk of infection is over.221–225

Please cite this article as: Forero E, Chalem M, Vásquez G, Jauregui E, Medina LF, Pinto Peñaranda LF, et al. Gestión de riesgo para la prescripción de terapias biológicas. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2016;23:50–67.