Sneddon syndrome is a rare non-inflammatory obliterative vasculopathy, characterized by the association of cardiovascular (arterial hypertension, intermittent claudication, and coronary artery disease) and neurological events (ischemic stroke, headache, dizziness and convulsions), and livedo reticularis/livedo racemosa. The case is presented of a woman admitted with an ischemic neurological disease, hypertension, vascular problems, and skin lesions. The skin biopsy was classified as surface perivascular lymphocytic dermatitis, suggestive of occlusive lesion.

El síndrome de Sneddon es una rara vasculopatía no inflamatoria, obliterante, caracterizada por la asociación de eventos cardiovasculares (hipertensión arterial, claudicación intermitente y enfermedad coronaria), neurológicas (accidentes cerebrovasculares isquémicos, cefalea, vértigo y convulsiones) y livedo reticularis de tipo racemosa. Presentamos a una mujer que ingresa con un cuadro neurológico isquémico, hipertensión arterial, problemas vasculares y lesiones en piel. La biopsia de piel se catalogó como dermatitis perivascular superficial linfocitaria, sugestivo de lesión oclusiva.

Sneddon syndrome (SS) described in 1965, is a non-inflammatory, obliterative thrombotic vasculopathy, characterized by the association of ischemic cerebrovascular events and livedo reticularis (LR) of racemose type.1

It is estimated that the incidence of SS is 4per million people per year and predominantly affects young women.

Neurological events such as transient ischemic disorders, headache, dizziness and convulsions, among others, can occur.2 The most frequent neurological manifestation is the transient ischemic attack, often in the territory of the middle cerebral artery, which entails contralateral hemiparesis, aphasia or visual field defects.

LR is caused by stenosis and occlusion of the small dermal arteries which lead to the reduction of the blood flow, causing decreased supply of oxygen in the affected vessels, producing the appearance of the skin in a reticular shape of purple or violaceous-cyanotic color3; it mainly affects the legs and arms, but it can also involve the buttocks and trunk, and it is aggravated by cold and pregnancy.

In SS the etiology is uncertain, in most cases is idiopathic,4 and it can be associated with autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome, Behçet's disease and mixed connective tissue disease.4–6

Below is reported the case of a woman admitted with a neurological condition, vascular problems and skin lesions; the clinical suspicion and the diagnostic aids allowed to establish the diagnosis.

Case reportA 41-year-old woman, coming from Chiclayo, was admitted to the emergency room. The patient consulted due to a holocranial headache of 7 days of evolution, of mild to moderate intensity, not associated with any other symptoms. Dysarthria and hemiparesis of the right hemibody were associated the day when she entered the emergency department.

As a relevant antecedent, at the age of 22 years the patient was diagnosed with high blood pressure with irregular treatment of enalapril and losartan. She also has the antecedent of diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) at the age of 26 years, without adherence to treatment and without having proper controls. As other antecedents, she refers having four pregnancies, one spontaneous abortion before 20 weeks, and three live births, 2 of which were premature with preeclampsia.

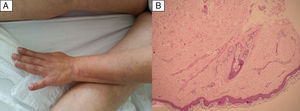

On physical examination she entered with a blood pressure of 170/120mmHg and a heart rate of 124beats/min. Pallor and LR were observed in the skin of the upper and lower limbs. Thorax and abdomen within normal parameters, neurological examination: awake, with dysarthria, positive right Babinski sign, right motor deficit, muscle strength of 4/5 in the right lower limb and 0/5 in the right upper limb. Glasgow Scale: eye opening 4/5, motor response 6/6 and verbal response 2/5, giving a score of 12/15.

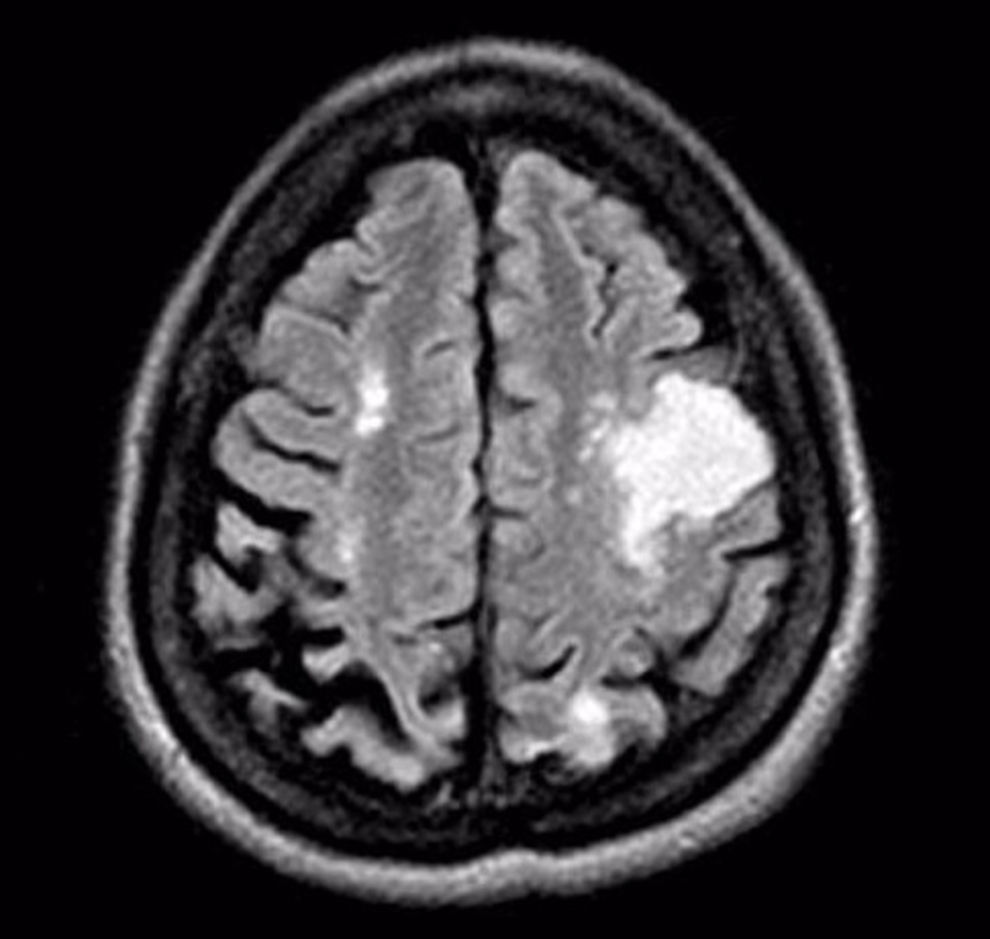

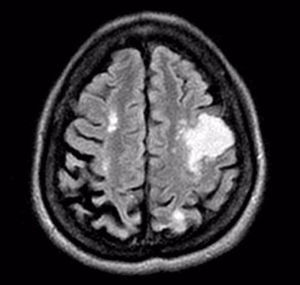

A magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was done during the hospitalization, evidencing cortical-subcortical and white matter lesions (Fig. 1).

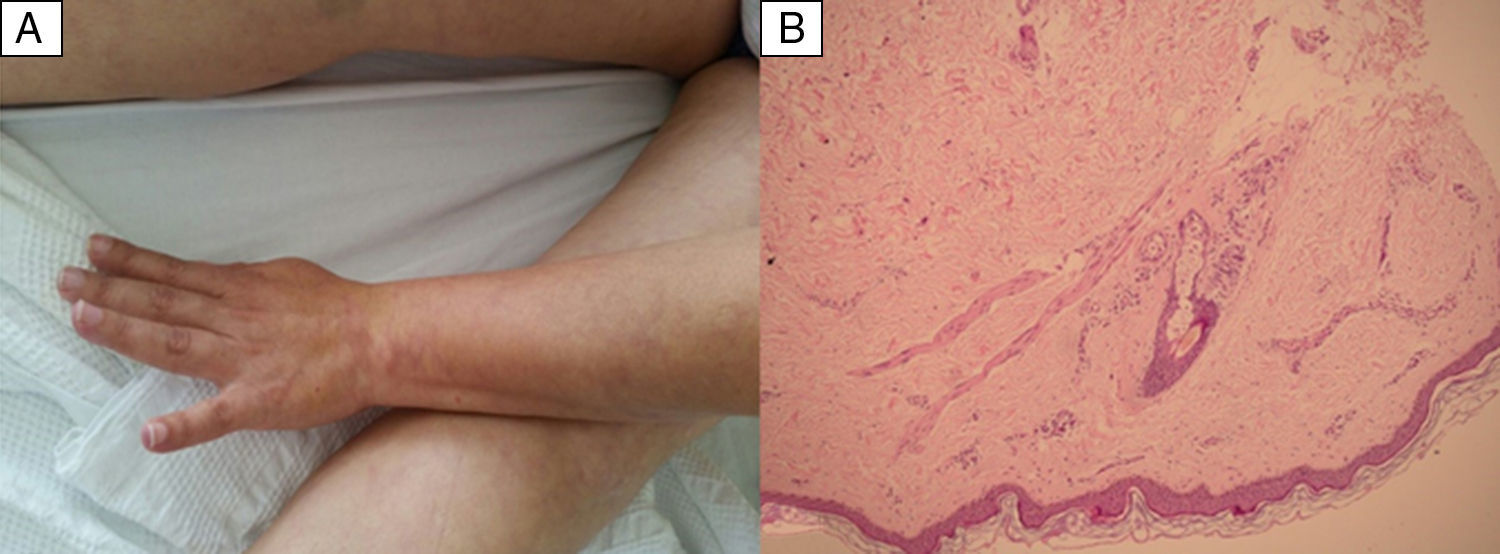

The skin biopsy was diagnosed as superficial perivascular lymphocytic dermatitis suggestive of occlusive lesion, (Fig. 2) confirming the LR.

Photo of the arm and thighs showing reticular shaped violaceous erythema, irregular livedo racemosa cutaneous lesions (A). Skin biopsy of livedo racemosa: mild superficial perivascular lymphocytic dermatitis, with mild dilation of the capillaries and moderate extravasation of the red blood cells. Fibrinoid necrosis is not found in the blood vessels. Suggestive of occlusive vascular pathology (B).

An echocardiogram was also performed, showing a moderate mitral insufficiency, with mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy. The fundoscopy did not show vasculitic lesions, but a cataract of the right eye was evidenced incidentally. In addition, bilateral diffuse nephropathy was found in the abdominal ultrasound.

In the immunological analyses were found: anti-B2 glycoprotein IgG: positive, anticardiolipin IgG: positive; anti-Smith, anti-lupus, ANA, ANCA, and ANTI-DNA, all were negative.

With the clinical suspicion and due to the fact of having LR along with the multi-infarct ischemic stroke, it was made the diagnosis of SS, associated with antiphospholipid syndrome by the immunological analyses.

The evolution of the patient was slow but favorable; and she was discharged 14 days after admission with oral anticoagulants.

DiscussionThe diagnosis of SS is based mainly on the skin biopsy and abnormal findings in the neurologic examination or in the magnetic resonance imaging.4,5 The clinical case we presented, met all the criteria to be classified as SS, in addition to this, it was evidenced to be associated with APS and other general problems such as mitral insufficiency, left ventricular hypertrophy, cataract on the right eye and diffuse bilateral nephropathy.

The APS is defined as the presence of lupus anticoagulant antibodies or anticardiolipin antibodies associated with vascular thrombosis or specific complications of pregnancy.6 The association of APS and LR has been closely related due to the thrombosis of the subcutaneous arterioles causing the reticular shaped purpuric coloration.3

Schellong et al., proposed 2 classifications for grouping the SS: Primary SS when no associated etiology is found; and SS secondary to an autoimmune disorder (APS) or to thrombophilia.7 However, approximately 60% of cases with SS have been associated with APS, indicating that this syndrome may be a distinct entity or perhaps a group of different disorders. Nevertheless, the existence of antiphospholipid antibodies suggests that the symptoms are secondary to thrombotic processes.

In our case we found other symptoms such as headache, hypertension, valvular heart diseases, diffuse nephropathy, ocular involvement and history of obstetric pathology. All these clinical symptoms are explained by the chronic occlusive compromise along with the pathology of antiphospholipid antibodies.

In the natural course of patients with SS, neurological events such as headache (62%) and dizziness (54%) have been recorded. In that study it was found that 54% had transient ischemic disorders during 6 years.2

It is important to determine the occurrence of cardiac manifestations in patients with SS. The studies suggest that the valvulopathy could be a source of emboli and a possible cause of the ischemic stroke. Multiple valve degenerations that require complex surgical interventions have been reported.8

Regarding the patients with SS without APS it was found that 52% had valvulopathies.9

It is necessary to be acquainted with the clinical features and the diagnosis of the SS in order to be able to investigate the pathogenesis and to obtain more etiological subgroups. Future therapy should identify the diverse treatment modalities for different etiological subgroups. The use of calcium blockers can reduce the skin symptoms, but it does not diminish the cerebrovascular complications,4 however, a recent research has shown improvement with the use of prostaglandins E1 (alprostadil) during 6 months.10 It has been reported a case of improvement of the neurological and cognitive symptoms in one patient, after 8 months of treatment with monthly intravenous cyclophosphamide.11

The prevention of smoking and the prevention of the use of oral contraceptives with estrogens can prevent or reduce the severity of the neurological symptoms and should be taken into account for this group of patients.4

In conclusion, in patients diagnosed with SS, an exhaustive search for autoimmune processes, thrombophilias and others, must be carried out. In addition, damage to other organs (cardiac, renal, neurological, ocular, etc.) should be prevented or diagnosed.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare they do not have any conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Carpio-Chaname CR, Vilchez-Rivera S, Failoc-Rojas VE. Síndrome de Sneddon asociado a síndrome antifosfolipídico: descripciones clínicas y revisión de la literatura. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2017;24:185–188.