The inflammatory process of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) is associated comorbidities. The JIA patients can fall behind their healthy peers, and motor and functional skills can reduce.

ObjectivesThe primary aim is to compare the motor skills of JIA patients with healthy controls. The secondary aim is to determine whether disease activity affects patients with JIA.

Materials and methodsFifteen patients with JIA and 15 healthy controls were included in the study. Motor skills were evaluated with Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency Second Edition Short Form (BOT-2 SF) in patients with JIA and healthy controls. BOT-2 SF measures four motor area composites with eight subtests. Disease activity was evaluated with Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score-27 (JADAS-27), disability level with Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (CHAQ-DI), and disease-related quality of life with Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) 3.0 Arthritis Module for JIA. According to disease activity, patients with JIA were divided into two groups as remission and active.

ResultsThe patients with JIA had significantly lower scores in the total and four motor area of BOT-2 SF compared to healthy controls (p<.05). When the remission and active groups were compared, there was no difference in the total and four motor area of BOT-2 SF, CHAQ-DI, or PedsQL (p>.05).

ConclusionThe motor skills of patients with JIA are lower than their healthy peers, and their motor skills, quality of life, and disability did not make a difference between the remission and active period.

El proceso inflamatorio de la artritis idiopática juvenil (AIJ) tiene comorbilidades asociadas. Los pacientes con AIJ pueden quedarse atrás de sus pares sanos y sus habilidades motoras y funcionales pueden reducirse.

ObjetivosEl objetivo principal de este trabajo es comparar las habilidades motoras de pacientes con AIJ y controles sanos, en tanto que el objetivo secundario es determinar si la actividad de la enfermedad afecta a los pacientes con AIJ.

Materiales y métodosEn el estudio se incluyeron 15 pacientes con AIJ y 15 controles sanos. Las habilidades motoras se evaluaron con Brunininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency Second Edition Short Form (BOT-2 SF) en pacientes con AIJ y controles sanos. El BOT-2 SF consta de 4 compuestos de área motora con 8 subpruebas. Las actividades de la enfermedad se evaluaron con Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score-27 (JADAS-27), el nivel de discapacidad con Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (CHAQ-DI) y la calidad de vida relacionada con la enfermedad con Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) 3.0, en tanto que para AIJ se empleó Arthritis Module. Según la actividad de la enfermedad, los pacientes con AIJ se dividieron en 2 grupos: en remisión y activos.

ResultadosLos pacientes con AIJ tuvieron puntuaciones significativamente más bajas en el área motora total, y 4 del BOT-2 SF en comparación con los controles sanos (p<0,05). Cuando se compararon los grupos de remisión y activo, no hubo diferencia en el área motora total ni en 4 de BOT-2 SF, CHAQ-DI y PedsQL (p>0,05).

ConclusiónLas habilidades motoras de los pacientes con AIJ son inferiores a las de sus pares sanos, y sus habilidades motoras, su calidad de vida y la discapacidad no marcaron una diferencia entre el periodo de remisión y el activo.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common rheumatic disease of childhood with unknown etiology but genetic and environmental factors are emphasized.1,2 JIA causes edema, effusion, tenderness, pain, limitation in joint movements, muscle weakness and muscle atrophy. For this reason, balance, gait and body coordination disorders are observed.3 At the same time, the inflammatory process that is characteristic of the disease and associated comorbidities causes fatigue, chronic pain, sleep problems, biopsychosocial influence as depression, anxiety, and school problems.4,5 These effects reduce the physical activity level of patients with JIA. Thus, they can fall behind their healthy peers, and motor and functional skills of JIA can reduce. This functional disability in patients with JIA leads to significant limitations in the performance of daily living activities such as school and playing.6

The problems caused by the inflammatory process in the hand and wrist of great importance in limitations of daily living activities.7 Fifty percent of children with JIA have a decrease in strength, especially in the upper extremities and mostly in hand strength.8 This may cause difficulties in hand coordination and fine motor activities such as school activities (writing, etc.), play activities and maintaining daily life activities in JIA. In addition, both symptoms and long-term treatments can change the quality of life as well as psychological and social functions of JIA.9,10

Motor skills, including postural, locomotor, and manual activities are very important for children's development.11 When motor skills emerge, they form the basis of development, opening up new opportunities for learning.12 Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency is a widely used battery to evaluate motor skill problems in patients with cerebral palsy, mental retardation, developmental coordination disorder, attention deficit and hyperactivity syndrome, and autism.13

While studies in the literature frequently examine the physical activity levels of patients with JIA. It will be important to evaluate both gross and fine motor skills in combination using a valid test battery. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate motor skills in patients with JIA using the Brunininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency Second Edition Short Form (BOT-2 SF) and compare them with healthy controls. The secondary aim is to determine whether disease activity affects patients with JIA in terms of motor skill, quality of life, and disability.

MethodsParticipantsFifteen patients with JIA followed by Pamukkale University and diagnosed by a rheumatologist s according to the diagnostic criteria of the International League Against Rheumatism between the ages of 4 and 19 year were included in the study. Participants who had difficulty in cooperation and had other diseases that would affect their functions (heart failure, lung pathology, etc.) were excluded. Fifteen healthy controls between the ages of 4–19 years were included in the control group and exclusion criteria were the same as for patients with JIA.

Ethical considerationsAll study procedures have been performed by the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval for the study was granted by the Pamukkale University Medical Ethics Committee (decision no: E-60116787-020-137046, dated: 30.11.2021). All patients were informed verbally and informed consent forms were signed.

MeasuresThe evaluations of all participants were made by the same investigator using the face-to-face interview method in same conditions according to standard test protocols. JADAS-27 was evaluated by the same rheumatologist blinded to all evaluations.

Personal and disease-related information of participants were recorded in the demographic registration form. Motor skill was evaluated with the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency Second Edition Short Form (BOT-2 SF) in patients with JIA and healthy controls. Disease activities were evaluated with Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score-27 (JADAS-27), disability level with Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (CHAQ-DI), and disease-related quality of life with Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) 3.0 Arthritis Module in patients with JIA. According to disease activity, patients with JIA were divided into two groups as remission and active according to the JADAS-27. Remission group consist of no disease activity patients with JIA and active group consist of the low, moderate, and high disease activity patients with JIA.

Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score-27 (JADAS-27)In 2009, “Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (JADAS)” was defined to assess disease activity in children. This scale consists of four sections: Doctor-Visual Analog Scale, Patient-Visual Analog Scale, number of active joints (71, 27, 10 joints), and sedimentation (between 0 and 10). JADAS is calculated by the arithmetic sum of four sections. In this study, JADAS-27 was used. JADAS-27 includes the cervical region, elbows, wrists, 1–3 metacarpophalangeal joints, proximal interphalangeal joints, hip joints, knees, and ankles.14 For JADAS-27; the score of ≤1 indicates no disease activity, the score from 1.1 to 2 indicates low disease activity, the score from 2.1 to 4.1 indicates moderate disease activity, and the score of >4.2 indicates high disease activity.15

Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (CHAQ-DI)CHAQ-DI was developed to assess functional abilities in children and can be applied to all children between the ages of 18 months and 18 years. It consists of 8 domains and 30 items. The total score ranges from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating higher disability.16

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) 3.0 Arthritis ModulePedsQL 3.0 Arthritis Module was developed to assess health-related quality of life in children with rheumatic disease. Its subtests with a total of 22 items were “Pain and Hurt”,” Daily activities”, “Treatment”, “Worry”, and “Communication”. PedsQL 3.0 Arthritis Module has child and parent forms separated according to different age groups as 2–4 years, 5–7 years, 8–12 years, and 12–18 years. In this study, child and parent forms for 8–12 years old and 12–18 years old were used. Higher total score means higher quality of life.17

Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency Second Edition Short Form (BOT-2 SF)BOT-2 SF measures fine and gross motor development in four motor area composites with eight subtests (46 items). The highest possible score is 88. Four motor areas were fine manual control (fine motor precision subtest and fine motor integration subtest), manual coordination (manual dexterity subtest and upper limb coordination subtest), body coordination (bilateral coordination subtest and balance subtest), and strength and agility (running speed and agility subtest and strength subtest). A high score indicates good motor skills.13

Statistical analysisWhen the study of Bos et al., which includes the “physical activity” parameter, is taken as a reference; the sample size was found to be 28 participants (minimum 14 per group), with a 95% confidence level, 80% power, and 1.00 effect size, using the G*Power 3.1.9.4. program.18 Data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) program. Mean±SD was given when parametric test assumptions were met, median (min/max) when parametric test assumptions were not met. Categorical variables were given as numbers and percentages. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test determined whether the data were suitable for normal distribution. In the comparison of independent group differences, the independent sample T test was used when the parametric test assumptions were met, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used when the parametric test assumptions were not met. A value of p<0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

ResultsNo problems for thirty participants were reported during evaluations. There was no statistical difference in the demographic and related disease data between the groups (p>0.05, Tables 1 and 2).

Demographic data of the participants.

| JIA (=15)Mean±SD | Healthy control (n=15)Mean±SD | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12.2±3.56 | 12.33±1.34 | 0.72* |

| Body weight (kg) | 46.40±19.70 | 48.30±14.27 | 0.90* |

| Height (cm) | 153.27±0.19 | 155.07±0.10 | 0.72* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.95±5.61 | 19.80±4.29 | 0.43* |

| Gender [n (%)] | |||

| Female | 9 (53.3) | 7 (53.3) | 0.46** |

| Male | 6 (46.7) | 8 (46.7) | |

JIA: juvenile idiopathic arthritis; BMI: body mass index; SD: standart deviation; p: significance value.

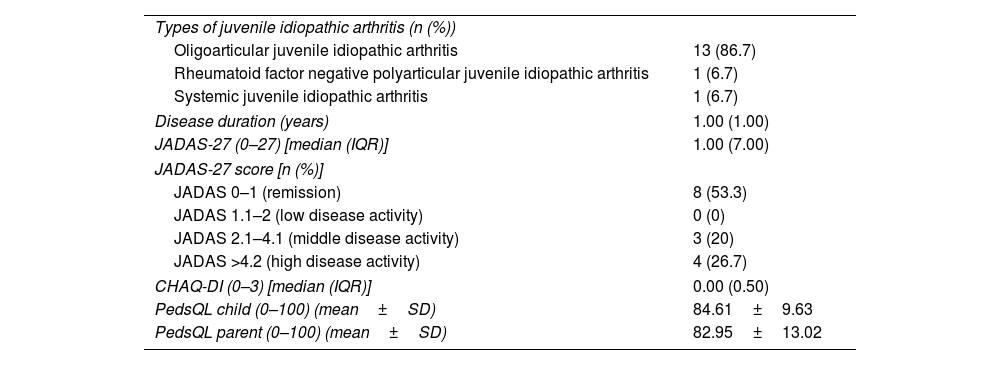

Disease-related data of children/adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

| Types of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (n (%)) | |

| Oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 13 (86.7) |

| Rheumatoid factor negative polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 1 (6.7) |

| Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 1 (6.7) |

| Disease duration (years) | 1.00 (1.00) |

| JADAS-27 (0–27) [median (IQR)] | 1.00 (7.00) |

| JADAS-27 score [n (%)] | |

| JADAS 0–1 (remission) | 8 (53.3) |

| JADAS 1.1–2 (low disease activity) | 0 (0) |

| JADAS 2.1–4.1 (middle disease activity) | 3 (20) |

| JADAS >4.2 (high disease activity) | 4 (26.7) |

| CHAQ-DI (0–3) [median (IQR)] | 0.00 (0.50) |

| PedsQL child (0–100) (mean±SD) | 84.61±9.63 |

| PedsQL parent (0–100) (mean±SD) | 82.95±13.02 |

JADAS-27: Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score-27; CHAQ-DI: Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; PedsQL: Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 3.0 Arthritis Module; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standart deviation.

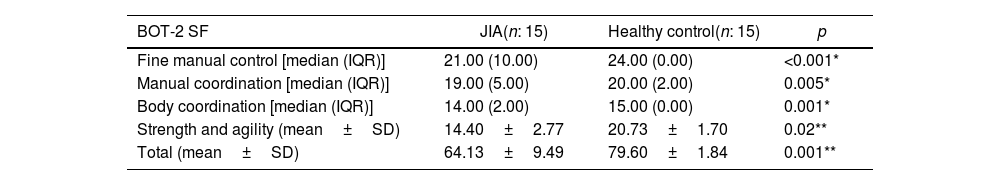

Patients with JIA had statistically significantly lower scores in BOT-2 SF total and four motor areas compared to healthy controls (p<0.05, Table 3).

Comparison of motor skill results between JIA and healthy control.

| BOT-2 SF | JIA(n: 15) | Healthy control(n: 15) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fine manual control [median (IQR)] | 21.00 (10.00) | 24.00 (0.00) | <0.001* |

| Manual coordination [median (IQR)] | 19.00 (5.00) | 20.00 (2.00) | 0.005* |

| Body coordination [median (IQR)] | 14.00 (2.00) | 15.00 (0.00) | 0.001* |

| Strength and agility (mean±SD) | 14.40±2.77 | 20.73±1.70 | 0.02** |

| Total (mean±SD) | 64.13±9.49 | 79.60±1.84 | 0.001** |

JIA: juvenile idiopathic arthritis; BOT-2 SF: Brunininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency Second Edition Short Form; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standart deviation; p: significance value.

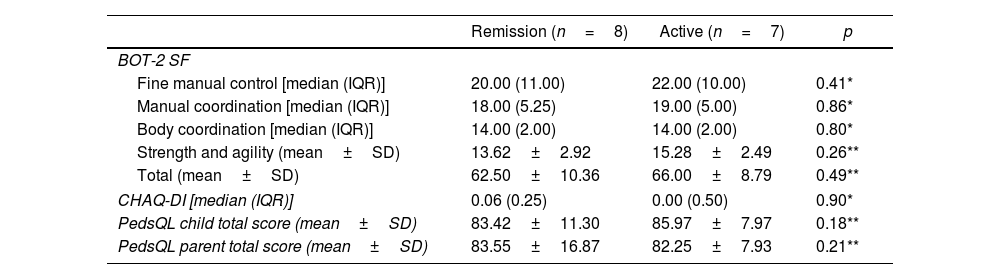

When the remission and active groups were compared, there was no difference in the total and four motor areas of BOT-2 SF, CHAQ-DI, and PedsQL score (p>0.05, Table 4).

Comparison of the results between groups according to disease activity.

| Remission (n=8) | Active (n=7) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BOT-2 SF | |||

| Fine manual control [median (IQR)] | 20.00 (11.00) | 22.00 (10.00) | 0.41* |

| Manual coordination [median (IQR)] | 18.00 (5.25) | 19.00 (5.00) | 0.86* |

| Body coordination [median (IQR)] | 14.00 (2.00) | 14.00 (2.00) | 0.80* |

| Strength and agility (mean±SD) | 13.62±2.92 | 15.28±2.49 | 0.26** |

| Total (mean±SD) | 62.50±10.36 | 66.00±8.79 | 0.49** |

| CHAQ-DI [median (IQR)] | 0.06 (0.25) | 0.00 (0.50) | 0.90* |

| PedsQL child total score (mean±SD) | 83.42±11.30 | 85.97±7.97 | 0.18** |

| PedsQL parent total score (mean±SD) | 83.55±16.87 | 82.25±7.93 | 0.21** |

BOT-2 SF: Brunininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency Second Edition Short Form; CHAQ-DI: Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; PedsQL: Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 3.0 Arthritis Module; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standart deviation; p: significance value.

In this study, motor skills have been comprehensively examined with different motor areas such as fine manual, manual coordination, body coordination, and strength and agility. The result of this study showed that the motor skills of JIA in these four different motor areas were lower than healthy controls. Another result was that there was no difference in motor skill levels, quality of life, and disability between disease activity groups.

There is no battery specifically developed to assess the physical fitness and motor skills of patients with JIA. In this study, BOT-2 SF was preferred to evaluate the affected joints and functions in JIA. Because, BOT-2 SF comprehensively evaluates parameters such as fine motor skills, coordination, balance, strength, and agility.

The first literature study, which reported that children with JIA have lower functional abilities than healthy children, was conducted by Miller et al.19 In the study, the inadequacies of children due to the problems in daily living activities were examined and compared using only the CHAQ questionnaire. However, this study was aimed to examine in detail the inadequacies of these patients by using performance tests. In line with the results of this study, Miller et al. also reported that the physical function of children with JIA was significantly impaired compared to healthy ones. This can be explained by reduced motor and functional ability, which limits school-age children's full participation in school activities and plays.19 At the same time, fatigue, chronic pain, joint stiffness, and deformities are frequently seen due to disease activity and inactivity. For this reason, patients have low activity levels from a young age, which may cause loss of function and motor control disorders, and significant problems may be observed in performing daily living activities.6,20

The studies examining disease activity and physical activity level in patients with JIA were reported that the level of physical activity decreased and was not associated with disease activity.18,21 In this study, the motor skills of patients with JIA between remission group and active group were similar but lower than their healthy peers. Although the diseases of patients with JIA are well managed and their disease activities are low, unfortunately, these patients lag behind healthy children in terms of motor skills. These results made us think that psychosocial factors as well as biological factors may be effective in the disability of patients with JIA. Both patients with JIA and their parents often experience significant psychosocial problems compared to healthy peers, due to physical impairments that limit basic motor skills.10

In this study, in addition to motor skills, the quality of life and disability levels of JIA between remission group and active group were found to be similar. This supports the conclusion that psychosocial factors can affect the results.22 Although the cut-off values of the PedsQL 3.0 Arthritis Module have not yet been determined,23 the low quality of life scores of both patients with JIA and their parents revealed the psychosocial impact of the disease from another perspective in this study. For this reason, even though their diseases are well controlled, we believe that patients with JIA will be more active in daily life by being supported in terms of physical activity/exercise, and this will be beneficial to reduce the psychosocial effect of the disease.

The most reported benefits of exercise training in JIA patients were increased range of motion, muscle strength, quality of life, functional performance, and improvement in clinical symptoms.24 In addition to preventing functional loss, exercise also contributes to the reduction of inflammation. Regular exercise is thought to have anti-inflammatory effects.25 Increased levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity and exercise can improve exercise capacity, the performance of daily activities, and overall quality of life.24 We think that patients with JIA who are supported by physical activity/exercise can approach the level of their healthy peers in terms of motor skill.

In JIA, synovitis and tenosynovitis in the hand and wrist can cause joint damage, loosening of ligaments, and instability of muscle functions. This process may cause serious deformities and lead to limitations in daily living activities.7 Handgrip strength was found to be significantly lower in both hands in patients with JIA compared to healthy controls.26,27 Hand and wrist dysfunction is very high, with more than half of the JIA children reporting hand or wrist-related problems at school.7 In addition, JIA patients with handwriting difficulties experience limitations in school mainly due to pain and inability to maintain handwriting for a longer period.28 In the study of Rashed et al., hand grip strength had a negative correlation with disease activity and disability level and hand grip strength had a positive correlation with the quality of life in the JIA.27 This study observed that the fine manual control score, which includes drawing and manual skills, decreased in children and adolescents with JIA compared to healthy controls.

Balance and coordination problems may occur in patients with JIA due to joint deformities, pain, and muscle weakness.3 Extension limitations in the knee and ankle, weakness of the quadriceps, hip extensors, and abductors affect balance and gait.29,30 Houghton et al. observed major impairments in one-leg balance and mild impairments in bilateral dynamic balance in children with JIA.31 In the study of Gizik et al., balance indices do not seem to result from variables related to disease activity.32 Body coordination of patients with JIA is also lower than their healthy peers was observed in this study. In light of these results, we think that it is important to include holistic exercise approaches, that provide sensory-motor integrity and mental unity such as yoga, pilates, and tai-chi. These exercise approaches can increase body awareness of patients with JIA, in exercise programs.

Patients with JIA were also less deficient in strength and agility than healthy controls. One study showed that children with JIA had weaker measures of muscle strength, including back strength and skeletal muscle mass than controls.26 Sit-up and push-up tests for strength evaluation and single-leg jump test for agility evaluation was used in this study. These tests are used to examine the large trunk muscles, and the strength of the trunk muscles. These muscles is important for the skills and strength transfer to the distal extremity. We recommended functional exercises based on trunk stabilization to increase the strength of large trunk muscles.

The limitation of this study was that most of the JIA patients were in the oligoarticular JIA according to the ILAR classification.

In future research, it is important to develop test batteries that can evaluate motor skills and physical fitness in patients with JIA, specifically. The absence of special batteries is an important issue that limits studies in this field. Also, motor skills are comparable by the types of JIA.

ConclusionsThe motor skills of patients with JIA were lower than their healthy controls. Because the motor skills of patients with JIA were low in both remission and active groups, there was no difference in terms of disease activity. Encouraging patients with JIA to physical activity/exercise can be important to increase participation in daily activities. Because fine motor skills, manual dexterity, upper extremity coordination, body coordination, balance, and strength and agility exercises were related to functional and motor skills, they can be included in the rehabilitation program. If patients with JIA are supported from a biopsychosocial perspective, there can be and improvement the quality of life and a decrease disability.

Ethical approvalAll study procedures have been performed by the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval for the study was granted by the Pamukkale University Medical Ethics Committee (decision no: E-60116787-020-137046, dated: 30.11.2021). All patients were informed verbally and informed consent forms were signed.

FundingThis study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.