In recent decades, the prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has increased thanks to early detection and the impact of new therapies on the survival of those affected. Up to 90% will have histopathological signs of kidney disease in the first 3 years of the disease, but lupus nephritis of clinical relevance will appear in 50% of cases, affecting kidney function and mortality. Despite aggressive therapeutic strategies, the prognosis of patients with LN remains unfavourable, mainly due to the high risk of progression to end-stage renal disease (10%–20%) and mortality from all causes.

ObjectiveTo describe the clinical and immunological risk factors of a group of patients with lupus, comparing clinical and serological characteristics in relation to renal involvement to establish possible associations.

Materials and methodsCross-sectional study in which 87 patients with SLE were included. Clinical and immunological variables were analyzed. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were performed using the presence of nephritis as an outcome.

ResultsThe prevalence of lupus nephritis was 59%. The significantly associated variables were arterial hypertension (OR 3.1, 95% CI 1.02–9.40), age of onset of lupus less than 25 years (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.08–6.73), the presence of reticular livedo (OR 4.1, 95% CI 1.09–15.7), positive anti-DNA (OR 2.9, 95% CI 1.18–7.24) and low levels of complement (OR 4.0, 95% CI 1.64–10.2).

ConclusionsUrinary sediment abnormalities were the most common renal manifestation and lupus debut before the age of 25 seems to increase the risk of developing nephritis. Future research is required for a better explanation of the associations found.

En las últimas décadas, la prevalencia del lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES) se ha incrementado gracias a la detección temprana y al impacto de las nuevas terapias en la sobrevida de los afectados. Hasta el 90% de ellos tendrá signos histopatológicos de afección renal en los primeros 3 años de la enfermedad, pero la nefritis lúpica (NL) de relevancia clínica aparecerá en el 50% de los casos, afectando la función renal y la mortalidad. A pesar de las estrategias terapéuticas agresivas, el pronóstico de los pacientes con NL sigue siendo desfavorable, principalmente debido al alto riesgo de progresión a enfermedad renal crónica terminal (10-20%) y de mortalidad por todas las causas.

ObjetivoDescribir los factores de riesgo clínicos e inmunológicos de un grupo de pacientes con lupus, comparando características clínicas y serológicas en relación con el compromiso renal, a fin de establecer posibles asociaciones.

Materiales y métodosEstudio de corte transversal en el que se incluyeron 87 pacientes con LES. Se analizaron variables clínicas e inmunológicas. Los análisis bivariado y multivariados se realizaron utilizando la presencia de nefritis como desenlace.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de NL fue del 59%. Las variables asociadas significativamente fueron hipertensión arterial (OR: 3,1; IC 95%: 1,02–9,40), edad de aparición del lupus menor de 25 años (OR: 2,7; IC 95%: 1,08–6,73), presencia de livedo reticularis (OR: 4,1; IC 95%: 1,09–15,7), anti-DNA positivo (OR: 2,9; IC 95%: 1,18–7,24) y niveles bajos de complemento (OR: 4,0; IC 95%: 1,64–10,2).

ConclusionesLas anormalidades en el sedimento urinario fueron la manifestación renal más común, en tanto que el inicio lúpico antes de los 25 años parece incrementar el riesgo de desarrollar nefritis. Se requieren futuras investigaciones que den una mejor explicación a las asociaciones encontradas.

Lupus nephritis (LN) is a frequent manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), characterized by proteinuria in variable range, whose clinical spectrum ranges from asymptomatic forms associated with microhematuria to nephrotic syndrome and kidney failure.1,2 The renal damage may be a consequence of glomerulonephritis caused by immune complexes, tubulointerstitial disease, or vascular involvement. Although it is estimated that up to 90% of the patients will have histopathological signs of renal involvement, clinically relevant nephritis will appear in 50% of the cases within the first 3 years of the disease.3 In up to half of the cases it is discovered during serial urine monitoring in asymptomatic patients, being proteinuria its hallmark and the main screening biomarker.4,5

Previous studies have linked younger age at onset of SLE, male gender, and non-Caucasian ethnicity as factors associated with the presence of LN.6–8 Despite aggressive therapeutic strategies, the prognosis of the patients with LN remains unfavorable, mainly due to the high risk of progression to end-stage chronic kidney disease (10%–20%) and of all-cause mortality.9 The objective of this study is to describe the characteristics and possible clinical factors associated with LN in a monocentric population of patients with SLE treated in a hospital in Argentina.

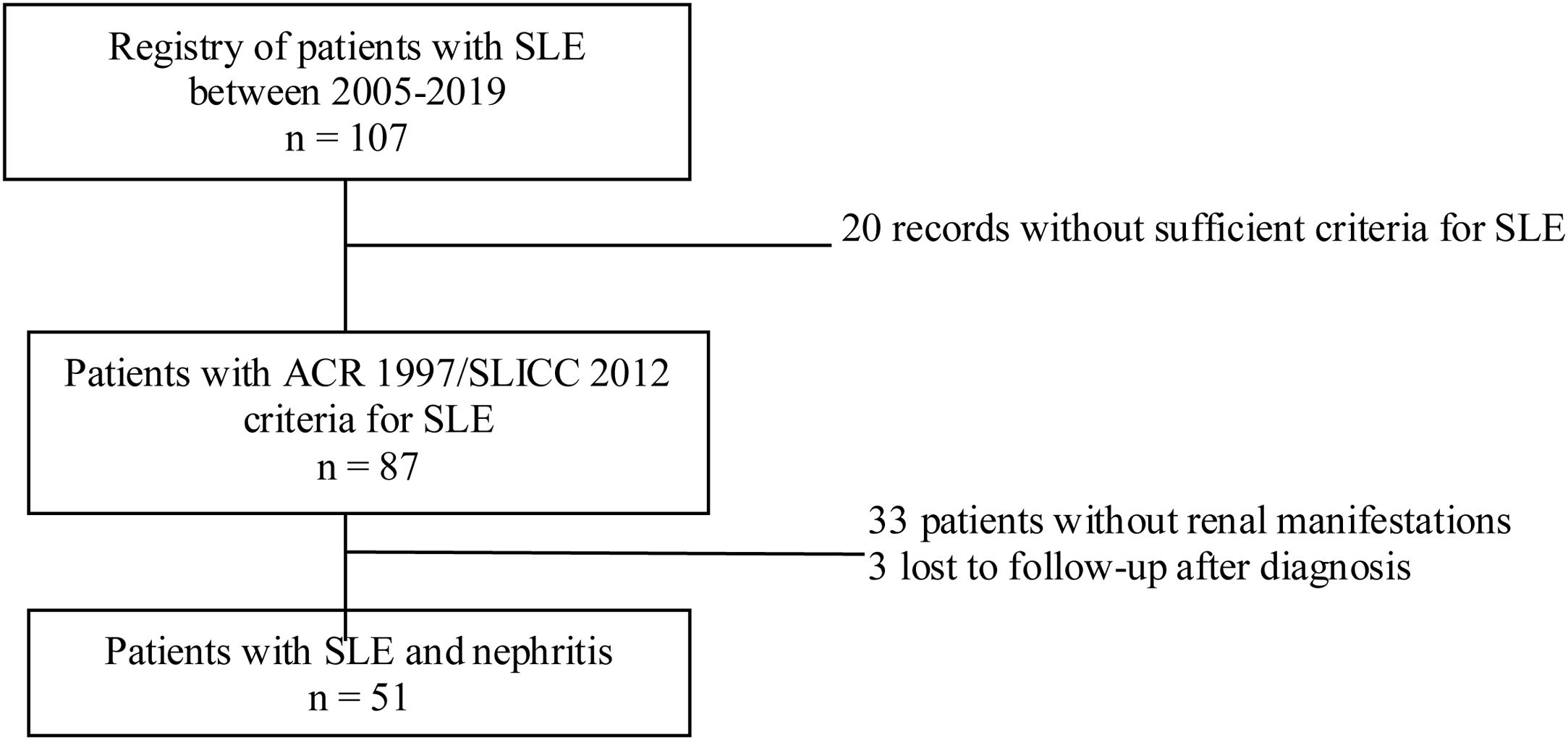

Materials and methodsStudy designDescriptive cross-sectional study of adult patients with SLE treated between the years 2005 and 2019 in the autoimmune diseases unit of the Private Community Hospital (Hospital Privado de Comunidad), Mar del Plata, Argentina. During the evaluation, a physician with experience in the management of patients with SLE was responsible for recording the information in a database. Sociodemographic, clinical and immunological variables were analyzed. The data analyzed were taken from reports of medical records, patients without ARC 1997 or SLICC 2012 criteria for SLE, pregnant women, children under 18 years of age, and patients with nephropathy prior to the diagnosis of lupus were excluded.10,11 In addition, patients with insufficient information related to the outcome under study were also excluded (Fig. 1).

Sociodemographic variablesThe age in years at the time of diagnosis of SLE, the biological sex, and the ethnic group were included, based on the self-definition of the patient according to his/her parents and 4 grandparents.

Clinical and immunological variablesAs for the clinical variables, extrarenal manifestations, comorbidities, and treatment received were considered. The following manifestations were evaluated: in skin and mucous membranes (malar rash, alopecia, discoid lesions, oral ulcers, livedo reticularis, Raynaud's phenomenon, purpura, photosensitivity); musculoskeletal (arthralgia/arthritis, avascular bone necrosis, myalgia/myositis, Jaccoud’s arthropathy); ocular (sicca syndrome, visual disorders); respiratory (pleurisy, lupus pneumonitis, pulmonary hemorrhage/vasculitis, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension); cardiovascular manifestations (pericarditis, valvulopathy, vasculitis, vascular thrombosis, arterial hypertension); neuropsychiatric (the 19 syndromes associated with SLE)12; gastrointestinal (serositis, hepatitis, enteropathy); hematological (hemolytic anemia, leukopenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemophagocytic syndrome, antiphospholipid syndrome) and renal: (at least one of the following criteria: persistent proteinuria [proteinuria >0.5 g/day, >3+ in test strips], persistent elevated creatinine and presence of active sediment [cellular or granular casts]).13 Urinary protein excretion >0.5 g/day was considered abnormal, while a value >3.5 g/day was considered as nephrotic-range proteinuria. The latter, associated with hypoalbuminemia and edema, was recognized as nephrotic syndrome, while a creatinine clearance <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (by CKD-EPI) or the presence of renal damage for 3 months or more was considered as chronic kidney disease.

A renal biopsy of patients with impaired renal function or any or the previously described criteria was requested, and the findings were classified according to the ISN/RPS 2003 criteria, by light and immunofluorescence study.14 The indexes of activity and chronicity, tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis were extracted from the disease reports contained in the medical records, calculated based on the NIH classification system. The degree of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy was categorized into polytomous variables (none to mild: <25% of the affected interstitium; moderate: 25%–50% and severe: >50%).15

The following serological variables were analyzed: antinuclear antibodies (ANA), total extractable nuclear antigen antibodies ENA (anti-Ro/SSa, anti-La/SSb, anti-Sm, anti-Scl-70 and anti-U1 RNP), anti-DNA, complement levels (C3 and C4), significant levels of anticardiolipin IgM/IgG and anti-B2-glycoprotein antibodies (>40 IU/ml), Coombs test and lupus anticoagulant. The following treatment variables were recorded: use of corticosteroids, prednisone or equivalents at low doses (<7.5 mg/day), intermediate doses (7.5–30 mg/day) and high doses (>30 mg/day), corticosteroid pulses,16 or the use of immunosuppressants administered for a minimum of 3 months, such as hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, rituximab, belimumab or other.

Statistical analysisFor the descriptive analysis, measures of central tendency and distribution of the variables under study were taken into account. Those of a quantitative nature and with a normal distribution are expressed by means, with their respective standard deviation, and those of non-normal distribution by medians with their respective interquartile range. Qualitative variables are presented in proportions. The Chi-square test was used for the bivariate analysis of the categorical variables, and the Fisher test for the analysis of cases in which the frequency of the event is lower than expected. For the quantitative variables with normal distribution, the Student’s t test was used, while in the case of quantitative variables with non-normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney U test was chosen. The potential risk variables were selected according to statistical and clinical criteria, while a binary logistic regression was performed to identify the effect of confounders, interaction, and mediation. The odds ratios (OR) of the risk variables are presented with their respective confidence interval using a level of statistical significance of p < 0.05. The analysis was carried out with the statistical package SPSS® Statistics version 25.

ResultsDuring the study period, 87 cases of SLE were registered, of which 90% (78) were women, with a sex ratio of 8.6:1. The most frequent ethnic self-denomination was mestizo (33%), followed by Caucasian (29%). The average age at the time of diagnosis was 32 ± 16 years. 74% of the cases had at least one concomitant disease. With regard to systemic manifestations, the most common were cutaneous, musculoskeletal, hematological, and renal. Among the cutaneous manifestations, the most frequent were: malar rash (51%), photosensitivity (44%), Raynaud’s phenomenon (44%), and alopecia (37%). The frequency of ANA, anti-DNA and the consumption of C3/C4 complement stand out in the immunological profile. The general characteristics of the population are described in Table 1.

General characteristics of the population (n = 87).

| Sociodemographic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 78 (90) |

| Male | 9 (10) |

| Age at diagnosis in years; mean (SD) | 32 (16) |

| Concomitant disease | 64 (74) |

| Autoimmune thyroid disease | 23 (26) |

| Osteoporosis | 15 (17) |

| Dyslipidemia | 14 (16) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (5) |

| Cardiovascular events | 6 (7) |

| Other | 2 (3) |

| Systemic manifestations | |

| Cutaneous | 75 (86) |

| Musculoskeletal | 74 (85) |

| Hematological | 56 (64) |

| Renal | 51 (59) |

| Cardiovascular | 36 (41) |

| Neuropsychiatric | 36 (41) |

| Ocular | 30 (35) |

| Respiratory | 24 (28) |

| Autoimmunity profile | |

| ANA | 78 (90) |

| Low complement | 61 (70) |

| Anti-DNA | 55 (63) |

| Treatments | |

| Corticosteroids | 79 (91) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 74 (85) |

| Azathioprine | 37 (43) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 26 (30) |

| Cyclophosphamide | 22 (25) |

| Methotrexate | 13 (15) |

ANA: antinuclear antibodies; SD: standard deviation.

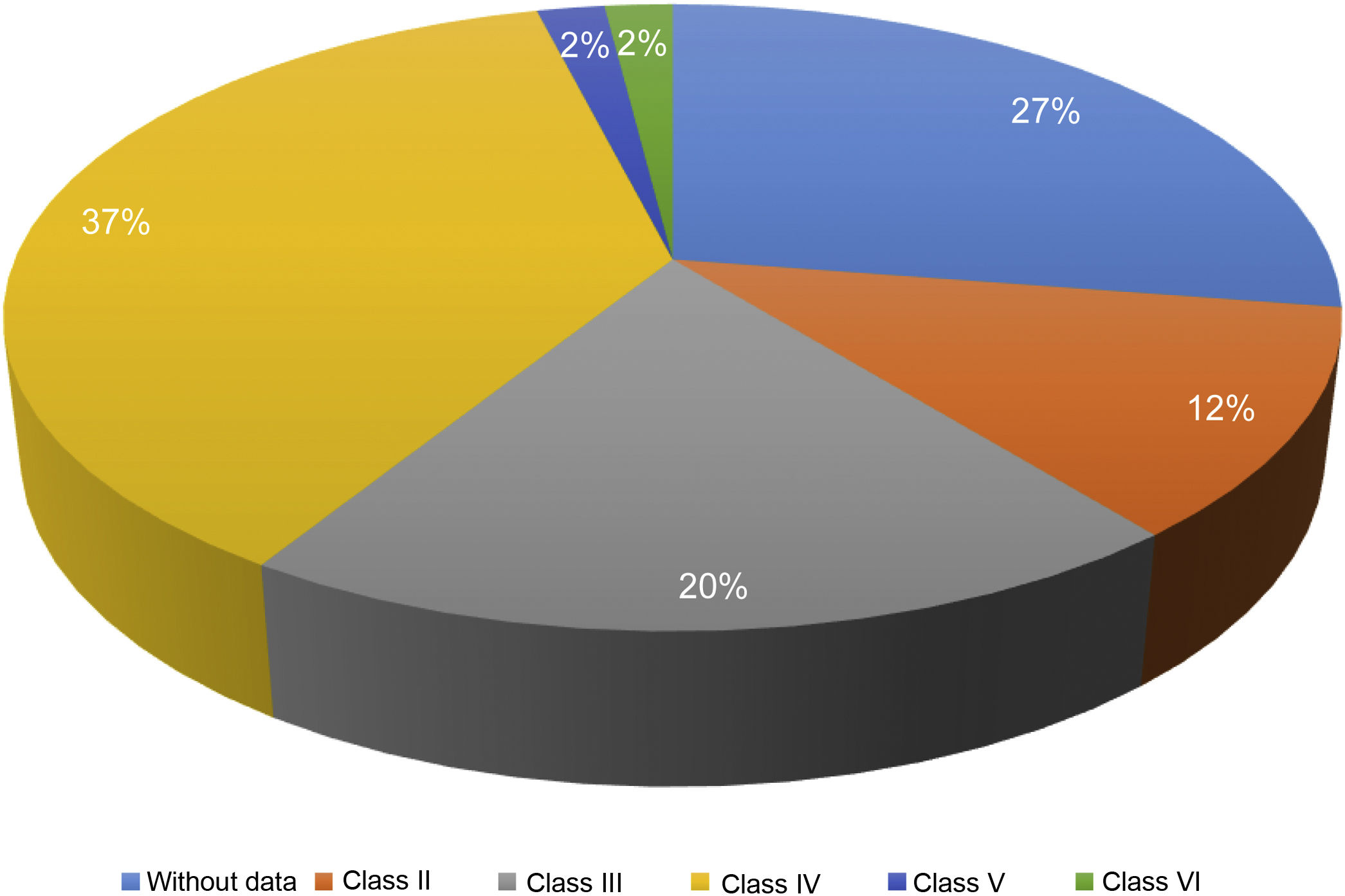

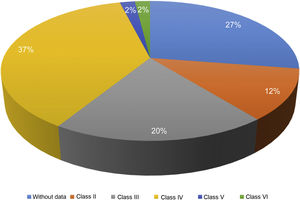

Of the 87 patients with SLE, 51 (59%) developed LN, of whom 86% were women. The median age at the time of diagnosis of SLE was 25 years (IQR = 20), among whom 22 (43%) were under 25 years of age. The main biochemical and histopathological characteristics of this subgroup are summarized in Table 2. 18% started with acute kidney failure and 45% developed chronic kidney disease (CKD). The report of the renal biopsy was obtained in 37 (72%) of those affected, from the clinical records. The distribution of the type of histopathological lesion was: diffuse proliferative nephritis (class IV) in 37% of patients, followed by focal proliferative nephritis (class III) in 20%, mesangial LN class II in 12%, class V LN in 2% and class VI in 2% (Fig. 2). Even though a renal biopsy of all patients with some type of renal involvement was requested, only the reports of 32 patients (72%) could be retrieved. The causes for non-performance include: refusal of the patient to undergo the procedure: 6 (42%), lack of health coverage for the procedure: 7 (50%) and absolute contraindication: 1 (8%).

Biochemical and histopathological characteristics in patients with LN (n = 51).

| Hematological and serological parameters | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Leukopenia (<4 × 109/l) | 24 (47) |

| Lymphopenia (lymphocytes <1500/l) | 23 (45) |

| Thrombocytopenia (<100 × 109/l) | 7 (14) |

| Positive ANA | 46 (90) |

| Positive anti-DNA | 38 (75) |

| C3, median (IQR), mg/dl | 78 (55–102) |

| C4, median (IQR), mg/dl | 15 (8–18) |

| Renal parameters | |

| Cr(s), median (IQR), mg/dl | 0.87 (0.73–1.16) |

| eGFR, mean, (SD), ml/min/1.73 m2 | 84 (33.5) |

| Proteinuria, median (IQR), mg/24 h | 787 (382−2,030) |

| Pathological urine sediment | 47 (92) |

| ISN/RPS pathology classification | |

| Class II | 6 (12) |

| Class III | 10 (20) |

| Class IV | 37 (37) |

| Class V | 1 (2) |

| Class VI | 1 (2) |

| NB | 14 (27) |

| Activity index, median, (IQR) | 3 (2−7) |

| Chronicity index, median, (IQR) | 1 (0−3) |

| Interstitial fibrosis | |

| None to mild (<25%) | 27 (53) |

| Moderate (25%–50%) | 10 (20) |

| Severe (>50%) | — |

| Tubular atrophy | |

| None to mild (<25%) | 27 (53) |

| Moderate (25%–50%) | 9 (18) |

| Severe (>50%) | 1 (2) |

ANA: antinuclear antibodies; Cr(s): serum creatinine; SD: standard deviation; LN: lupus nephritis; IQR: interquartile range; NB: without biopsy report; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

Regarding corticosteroid therapy, it was found that high doses of prednisone were prescribed in more than half of the cases (51%), requiring the use of intravenous pulses at some point in the course of the disease in 50%. HCQ was the second most used drug, followed by AZA (43%), MFM (30%), and CPM (25%). The use of biological drugs was 2%. In cases of LN with class III and IV histopathological lesions, at least 4 drugs were required within the treatment scheme, always including a corticosteroid.

Analysis of factors associated with lupus nephritisWithin the clinical variables, the age under 25 years, the presence of livedo reticularis, arterial hypertension, the presence of positive anti-DNA and the consumption of complement were associated with the presence of LN, with a statistically significant association. No association was found between gender and renal involvement (Table 3).

Risk factors associated with NL.

| Factor | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (<25 years)a | 2.7 | 1.08–6.73 | 0.025 |

| Livedo reticularis | 4.1 | 1.09–15.77 | 0.027 |

| Arterial hypertension | 3.1 | 1.02–9.40 | 0.040 |

| Positive anti-DNA | 2.9 | 1.18–7.24 | 0.019 |

| Low C3 | 4.0 | 1.64–10.20 | 0.002 |

| Low C4 | 3.8 | 1.40–10.48 | 0.007 |

SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; LN: lupus nephritis.

Our study included 87 patients with SLE, 59% of whom developed LN; both their distribution by sex and the average age at the time of diagnosis of SLE were relatively similar to those previously published in Argentina and Latin America.17,18 Aggressive phenotypes of the disease may be expressed more frequently in males. In the GLADEL cohort, it was observed a higher prevalence of LN in men (58.5 vs. 44.2%; p = 0.004).19 In our study, no significant differences were found in the prevalence of LN between both genders (56.4 vs. 77.7%; p = 0.218), which could be explained by the low proportion of male patients recruited. Regarding the age of onset of SLE, early age has been described as a prognostic factor for the appearance of the renal involvement.20 In our cohort, it was observed that the onset of SLE before the age of 25 years is associated with a 2.7-fold increased risk of developing nephritis.

Abnormalities in the urine sediment such as microhematuria and cellular casts were the most common renal manifestations. Since their presence is usually asymptomatic, it is really important to carry out systematic urine monitoring in asymptomatic patients or during the evaluation for a lupus relapse. In the majority of cases, renal manifestations occur during the course of the disease, when the diagnosis of lupus has already been established (5.3 vs. 51.7%, respectively, in the GLADEL cohort).18 The detection of LN in early or asymptomatic stages could imply better results after the application of immunosuppressive treatment.

On the other hand, our data showed a significant statistical association between the presence of LN and the occurrence of livedo reticularis and arterial hypertension as symptoms in the evolution of SLE, regardless of the time of onset. In lupus, livedo reticularis may be a sign of the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies.21 In our cohort, no significant differences were found between the patients who presented livedo reticularis and positive IgG anticardiolipin antibodies (52.9 vs. 47.1%; p = 0.085). The underlying pathophysiological mechanism that explains the high prevalence of arterial hypertension in lupus patients has not been elucidated. Although the glomerular damage and the renal vascular endothelial dysfunction are probable contributors, hypertension can also be present in patients without renal compromise. Several mechanisms have been proposed for this association.22.

LN typically develops early in the course of the disease, usually within the first 6-36 months23; therefore, the active search for markers of kidney injury should be a constant in clinical practice, with the subsequent histopathological study in those in whom renal involvement is suspected.24,25

In conclusion, it is possible to affirm that the analyzed cohort of patients with LN, due to its demographic and clinical characteristics, is a population similar to that of other geographical areas, and that both the systematic search and the early recognition of renal damage are simple strategies that can determine the clinical outcome in terms of morbidity.

LimitationsThe limitations of the present study are mainly derived from those related to the cross-sectional design and the loss of data related to renal biopsies. Although the findings allow us to generate hypotheses, they are limited when it comes to establishing causality and temporal association, so that, even if it would be interesting to evaluate the evolution to chronic kidney disease, this type of analysis is not methodologically correct. There could be the presence of selection or information biases, as well as of confusion, due to the origin of the data analyzed, records from a database.

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the Institutional Council for the Review of Research Studies (CIREI, for its acronym in Spanish) and informed consent was obtained from the patients.

FundingNo entity provided economic funding for the study and the preparation of the article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest for the preparation of this article.