In clinical practice, there is no specific recommendation on when to take samples in case of clinical suspicion of antiphospholipid syndrome, only a list of factors that generate APS risk, without adequately quantifying the weight of each of these factors.

Materials and methodsAnalytical observational case-control study, nested in a retrospective cohort of patients with venous or arterial thrombosis in whom antiphospholipid syndrome was clinically suspected. Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome according to the Sapporo criteria or triple positive initial result (cases) are compared with patients negative for APS (controls). The association between the diagnosis of APS and different clinical and paraclinical factors was evaluated.

Results68 patients were included (72% women, 41.2% with deep venous thromboembolism and 29.4% with pulmonary embolism). In 18 SAF was confirmed. There were no significant differences in age in patients with and without confirmation of the diagnosis (44.0±17.9 vs. 51.2±14.9, p = 0.069). In the multivariate analysis, a significant and independent association was found between having APS and rheumatic disease (OR 12.1, p = 0.02), PTT prolongation (OR 17.6, p = 0.014), platelet count < 150000 (OR 18.6, p = 0.008), and a history of previous thrombosis events (OR: 6.1 for each event, p = 0.027).

ConclusionsIn patients with arterial or venous thrombosis, there is a greater possibility of confirming antiphospholipid syndrome if there is a history of rheumatic disease, prolongation of PTT to more than 5 seconds, thrombocytopenia, and previous events of thrombotic disease. In these patients it is advisable to search for APS, in order to prevent new events.

En la práctica clínica, la sospecha de síndrome antifosfolípido (SAF) se basa en las recomendaciones de las guías sobre a quienes tomar muestras ante los factores que generen riesgo de SAF. Sin embargo, estas recomendaciones se basan en el consenso de expertos, dado que no se ha cuantificado adecuadamente el peso de cada uno de esos factores.

Materiales y métodosEstudio observacional analítico de casos y controles, anidado en una cohorte retrospectiva de pacientes con trombosis venosa o arterial en quienes se sospechó clínicamente SAF. Se compararon los pacientes con diagnóstico confirmado de SAF según criterios de Sapporo o resultado inicial triple positivo (casos) con los pacientes negativos para SAF (controles). Se evaluó la asociación entre el diagnóstico de SAF y diferentes factores clínicos y paraclínicos.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 68 pacientes (72% mujeres, 41,2% trombosis venosa profunda, 29,4% tromboembolismo pulmonar). En 18 casos se confirmó SAF. No hubo diferencias significativas de edad en pacientes con y sin confirmación del diagnóstico (44,0±17,9 vs. 51,2±14,9, p = 0,069). En el análisis multivariado se encontró una asociación entre tener síndrome antifosfolipido y enfermedad autoinmune (OR 12,1; IC 95% 1,47-99,00; p = 0,02), prolongación del PTT (OR 17,6; IC 95% 1,80–172,33; p = 0,014), trombocitopenia < 150.000 (OR 18,6; IC 95% 2,18–158,87; p = 0,008) y antecedente de eventos previos de trombosis (OR: 6,1 por cada evento; 1,23–30,52; p = 0,027).

ConclusionesEn los pacientes con trombosis arterial o venosa existe una mayor posibilidad de confirmar SAF en aquellos con antecedentes de enfermedad autoinmune, prolongación del PTT mayor de 5 segundos, trombocitopenia y eventos previos de enfermedad trombótica. En estos casos es recomendable solicitar anticuerpos para síndrome antifosfolipido.

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by obstetric morbidity and venous or arterial thrombosis in the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies. Its estimated prevalence ranges from 6.19 to 50 cases per 100,000 individuals.1 Early diagnosis is crucial, as moderate- and high-risk profiles increase the probability of venous thrombosis from 42 to 59.2 Identifying and treating these patients (typically with warfarin) can prevent further thrombotic events. Management guidelines from the British Society for Haematology (BSH3,4 and the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH5 recommend that anticoagulation therapy continue indefinitely following an arterial or venous thrombotic event. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) guidelines4 also recommend indefinite anticoagulation, except in cases of the first event caused by a non-high-risk pattern without risk factors for recurrence.

The APS classification criteria were first defined in Sapporo in 1998 and modified in Sydney in 2006.6 According to this definition, a diagnosis requires a history of either a thrombotic or obstetric event associated with persistent positivity (in two samples taken at least 12 weeks apart) for IgM or IgG β2-glycoprotein antibodies, IgG or IgM anticardiolipin antibodies, and lupus anticoagulant.

In general, management guidelines for antibody testing in APS suggest that it should be considered for subjects with a family history of APS, recurrent venous thrombosis, multiple thrombi, thrombosis in unusual sites, or for individuals under 50 years of age at the time of an unprovoked thrombotic event.7–10 However, clinical practice does not provide specific recommendations on whom to test. Instead, it offers a list of risk factors for APS, whose relative importance has not been adequately quantified. As a result, the decision to request antibody tests often relies on the clinical judgment of the treating physician. This may lead to unnecessary testing, which can increase healthcare costs. The prevalence of positive APS antibodies in patients with thrombotic events does not exceed 26.1%,11 making universal testing inefficient.

To address this issue, it is important to identify and quantify the clinical and paraclinical variables that can help pinpoint patients more likely to have APS. The aim of this study is to assess, in individuals with arterial and venous thrombotic events, the demographic, clinical, and paraclinical factors that predict the clinical diagnosis of APS, based on a cohort of patients treated at a reference institution in Colombia.

Materials and methodsAn analytical observational case-control study nested within a historical cohort was conducted, evaluating patients with thrombotic events treated at a university hospital in Colombia between September 2019 and January 2023. The study included individuals over 18 years of age who had a thrombotic event upon admission, such as proximal deep vein thrombosis, distal deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary thromboembolism, portal thrombosis, venous sinus thrombosis, splenic vein thrombosis, renal vein thrombosis, mesenteric venous thrombosis, internal jugular thrombosis, or arterial thrombosis. These patients were also suspected of hypercoagulability, as determined by the attending physician, who requested antiphospholipid antibody testing. Patients with conditions that could generate false-positive antiphospholipid antibodies—such as hepatitis C, hepatitis B, syphilis, HIV infection, hematological, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and pulmonary malignancies, and those who were pregnant—were excluded from the study.

Subjects were identified from the anticoagulation clinic’s patient records. Among them, individuals who had a new diagnosis of a thrombotic event and had undergone antiphospholipid antibody testing for suspected hypercoagulability were selected. Clinical and paraclinical data were collected from the hospital’s electronic medical records using a standardized data collection form. This information included demographic variables, history of abortion, prior thrombotic events, other autoimmune diseases (such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, inflammatory myopathy, etc.), use of oral contraceptives, type of thrombotic event at admission, partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and platelet count at the time of the event (with thrombocytopenia defined as a platelet count below 150,000/mm³). Additionally, antiphospholipid antibody results (IgM and IgG anticardiolipin antibodies, IgM and IgG anti-β₂-glycoprotein antibodies, and lupus anticoagulant) were recorded. If the initial APS test results were positive, a confirmatory test result, taken at least 12 weeks later, was sought from the clinical records.

For the analysis, four groups were created: (1) confirmed positive patients—those who met the Sapporo classification criteria for APS12; (2) triple-positive subjects —those with three positive tests in the initial measurement, considered to be at up to 33 times greater risk of thrombosis13; (3) individuals who tested positive in the initial measurement (one or two positive tests) but did not confirm positivity at 12 weeks; and (4) negative patients—those with an initially negative test result or an initially positive result followed by a negative test at 12 weeks. The laboratory cut-off values for anticardiolipin and β₂-glycoprotein antibodies were 20 GP L U/mL for IgG and 20 MP L U/mL for IgM. The cut-off point for the lupus anticoagulant ratio was greater than 1.2. Using a cut-off point lower than that recommended by the Sapporo criteria has been shown in other studies to be a risk factor for thrombosis.14 The enzyme immunoassay technique was used to process the measurements.

For descriptive analysis, absolute frequencies were reported, and proportions were used for categorical variables. For continuous variables, measures of central tendency (mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range) were used, depending on the data distribution. The Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to assess the normality assumption. For subgroup comparisons, the χ², Mann-Whitney U, or T-tests were used based on the variable type. The Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to compare continuous variables across three or more groups. Finally, for logistic regression analysis, subjects who met the Sapporo classification criteria or had a triple-positive result were defined as cases (groups 1 and 2), while negative patients were used as controls (group 4). The association between each factor and the diagnosis of APS was first assessed in a univariate analysis, followed by a multivariate analysis that initially included all variables associated with APS in the univariate analysis, as well as those described in previous studies. Variables were then selected using the stepwise backward method, and only those with a statistically significant association (p < 0.05) were included in the final model. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata Statistical Software (Release 16, TX: StataCorp LP).

Ethical considerationsThe protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the hospital where the research was conducted, by the WHO ethical guidelines (Declaration of Helsinki) on human experimentation. In compliance with Resolution 8430 of 1993, this study is categorized as safe research. As it is a retrospective cohort study based on a database, informed consent was not obtained. The authors declare that this article does not contain any personal information that could identify the patients.

Results

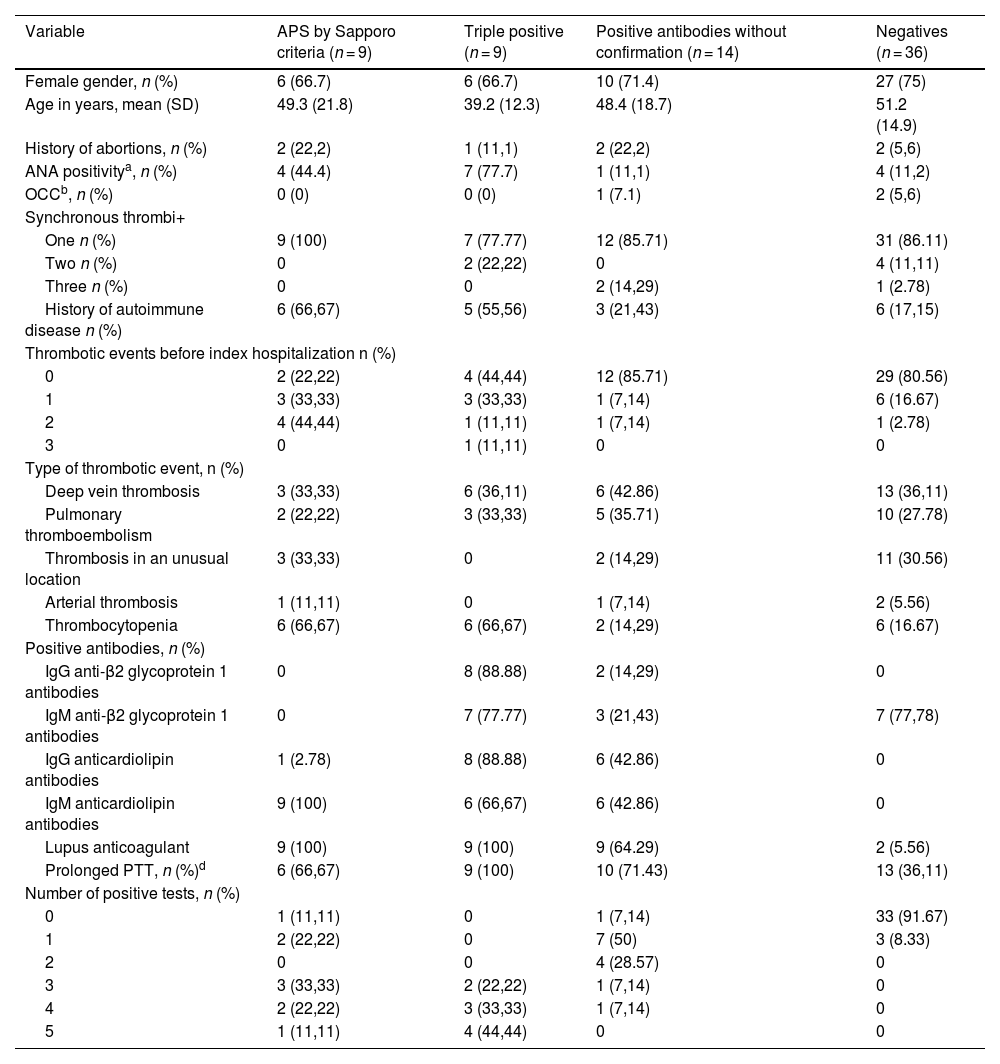

The analysis included 68 patients: 9 who met the Sapporo criteria (Group 1), 9 who were triple-positive at the initial measurement (Group 2), 14 who were positive at the initial test without subsequent confirmation (Group 3), and 36 who were negative (Group 4). Clinical and demographic characteristics, according to the analysis group, are presented in Table 1. The mean age across the different groups ranged from 39 to 52 years. Most of the patients were women (72%), and the most common types of thrombotic events were deep vein thrombosis (41.2%) and pulmonary thromboembolism (29.4%). Clinical features and APS positivity were similar among the four patients who experienced arterial thrombosis.

Demographic and clinical variables of the patients included.

| Variable | APS by Sapporo criteria (n = 9) | Triple positive (n = 9) | Positive antibodies without confirmation (n = 14) | Negatives (n = 36) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender, n (%) | 6 (66.7) | 6 (66.7) | 10 (71.4) | 27 (75) |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 49.3 (21.8) | 39.2 (12.3) | 48.4 (18.7) | 51.2 (14.9) |

| History of abortions, n (%) | 2 (22,2) | 1 (11,1) | 2 (22,2) | 2 (5,6) |

| ANA positivitya, n (%) | 4 (44.4) | 7 (77.7) | 1 (11,1) | 4 (11,2) |

| OCCb, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) | 2 (5,6) |

| Synchronous thrombi+ | ||||

| One n (%) | 9 (100) | 7 (77.77) | 12 (85.71) | 31 (86.11) |

| Two n (%) | 0 | 2 (22,22) | 0 | 4 (11,11) |

| Three n (%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (14,29) | 1 (2.78) |

| History of autoimmune disease n (%) | 6 (66,67) | 5 (55,56) | 3 (21,43) | 6 (17,15) |

| Thrombotic events before index hospitalization n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 2 (22,22) | 4 (44,44) | 12 (85.71) | 29 (80.56) |

| 1 | 3 (33,33) | 3 (33,33) | 1 (7,14) | 6 (16.67) |

| 2 | 4 (44,44) | 1 (11,11) | 1 (7,14) | 1 (2.78) |

| 3 | 0 | 1 (11,11) | 0 | 0 |

| Type of thrombotic event, n (%) | ||||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 3 (33,33) | 6 (36,11) | 6 (42.86) | 13 (36,11) |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | 2 (22,22) | 3 (33,33) | 5 (35.71) | 10 (27.78) |

| Thrombosis in an unusual location | 3 (33,33) | 0 | 2 (14,29) | 11 (30.56) |

| Arterial thrombosis | 1 (11,11) | 0 | 1 (7,14) | 2 (5.56) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 6 (66,67) | 6 (66,67) | 2 (14,29) | 6 (16.67) |

| Positive antibodies, n (%) | ||||

| IgG anti-β2 glycoprotein 1 antibodies | 0 | 8 (88.88) | 2 (14,29) | 0 |

| IgM anti-β2 glycoprotein 1 antibodies | 0 | 7 (77.77) | 3 (21,43) | 7 (77,78) |

| IgG anticardiolipin antibodies | 1 (2.78) | 8 (88.88) | 6 (42.86) | 0 |

| IgM anticardiolipin antibodies | 9 (100) | 6 (66,67) | 6 (42.86) | 0 |

| Lupus anticoagulant | 9 (100) | 9 (100) | 9 (64.29) | 2 (5.56) |

| Prolonged PTT, n (%)d | 6 (66,67) | 9 (100) | 10 (71.43) | 13 (36,11) |

| Number of positive tests, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 1 (11,11) | 0 | 1 (7,14) | 33 (91.67) |

| 1 | 2 (22,22) | 0 | 7 (50) | 3 (8.33) |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 (28.57) | 0 |

| 3 | 3 (33,33) | 2 (22,22) | 1 (7,14) | 0 |

| 4 | 2 (22,22) | 3 (33,33) | 1 (7,14) | 0 |

| 5 | 1 (11,11) | 4 (44,44) | 0 | 0 |

APS: Antiphospholipid síndrome; ANA: Antinuclear antibodies; OCC: Oral contraceptives.

cPlatelet level <150,000/mm3.

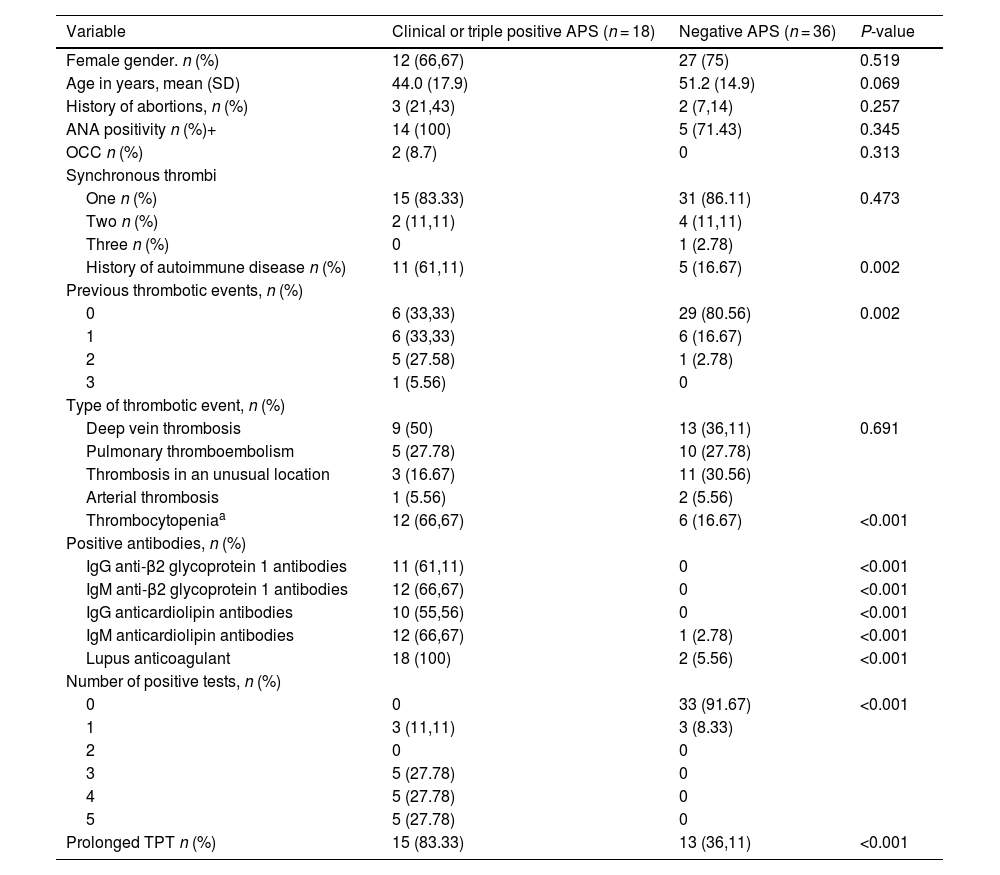

Table 2 compares patients with a confirmed diagnosis of APS or triple positivity (Groups 1 and 2) with those who were negative (Group 4). No significant differences were found in age (44.0±17.9 vs. 51.2±14.9; p = 0.069), but there was a higher frequency of a history of autoimmune disease (61.1% vs. 16.7%; p = 0.002) and previous thrombotic events (p = 0.002). Similarly, in the group of patients with confirmed APS, a prolongation of at least 5 seconds in the PTT (83.3% vs. 36.1%; p < 0.001) and thrombocytopenia (66.7% vs. 16.7%; p < 0.001) were more frequent.

Comparison between patients with clinical or triple positive APS vs. negative APS.

| Variable | Clinical or triple positive APS (n = 18) | Negative APS (n = 36) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender. n (%) | 12 (66,67) | 27 (75) | 0.519 |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 44.0 (17.9) | 51.2 (14.9) | 0.069 |

| History of abortions, n (%) | 3 (21,43) | 2 (7,14) | 0.257 |

| ANA positivity n (%)+ | 14 (100) | 5 (71.43) | 0.345 |

| OCC n (%) | 2 (8.7) | 0 | 0.313 |

| Synchronous thrombi | |||

| One n (%) | 15 (83.33) | 31 (86.11) | 0.473 |

| Two n (%) | 2 (11,11) | 4 (11,11) | |

| Three n (%) | 0 | 1 (2.78) | |

| History of autoimmune disease n (%) | 11 (61,11) | 5 (16.67) | 0.002 |

| Previous thrombotic events, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 6 (33,33) | 29 (80.56) | 0.002 |

| 1 | 6 (33,33) | 6 (16.67) | |

| 2 | 5 (27.58) | 1 (2.78) | |

| 3 | 1 (5.56) | 0 | |

| Type of thrombotic event, n (%) | |||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 9 (50) | 13 (36,11) | 0.691 |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | 5 (27.78) | 10 (27.78) | |

| Thrombosis in an unusual location | 3 (16.67) | 11 (30.56) | |

| Arterial thrombosis | 1 (5.56) | 2 (5.56) | |

| Thrombocytopeniaa | 12 (66,67) | 6 (16.67) | <0.001 |

| Positive antibodies, n (%) | |||

| IgG anti-β2 glycoprotein 1 antibodies | 11 (61,11) | 0 | <0.001 |

| IgM anti-β2 glycoprotein 1 antibodies | 12 (66,67) | 0 | <0.001 |

| IgG anticardiolipin antibodies | 10 (55,56) | 0 | <0.001 |

| IgM anticardiolipin antibodies | 12 (66,67) | 1 (2.78) | <0.001 |

| Lupus anticoagulant | 18 (100) | 2 (5.56) | <0.001 |

| Number of positive tests, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 33 (91.67) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 3 (11,11) | 3 (8.33) | |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 5 (27.78) | 0 | |

| 4 | 5 (27.78) | 0 | |

| 5 | 5 (27.78) | 0 | |

| Prolonged TPT n (%) | 15 (83.33) | 13 (36,11) | <0.001 |

APS: Antiphospholipid síndrome; ANA: Antinuclear antibodies; OCC: oral contraceptives.

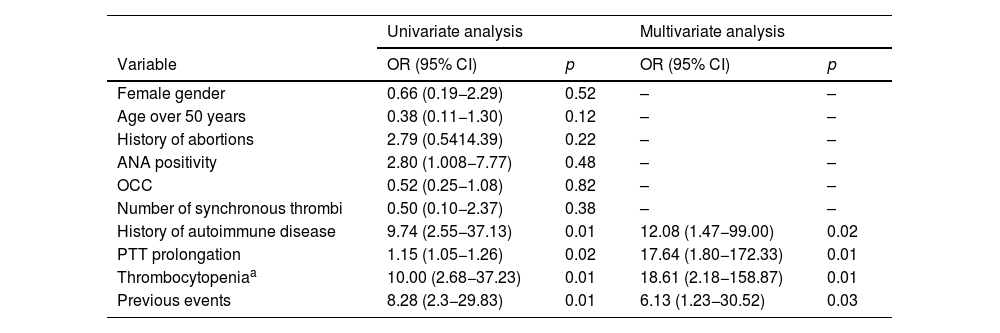

Table 3 presents the univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with the diagnosis of clinical APS or triple antibody positivity. In the univariate analysis, a history of autoimmune disease (OR: 9.74; 95% CI: 2.55−37.13; p = 0.01), PTT prolongation of more than five seconds (OR: 1.15; 95% CI: 1.05−1.26; p = 0.02), thrombocytopenia (OR: 10.0; 95% CI: 2.68−37.23; p = 0.01), and previous events (OR: 8.28; 95% CI: 2.3−29.83; p = 0.01) were associated with the diagnosis of clinical APS. In the multivariate analysis, the factors independently associated with this diagnosis were the presence of autoimmune disease (OR: 12.1; 95% CI: 1.47−99.00; p = 0.02), PTT prolongation (OR: 17.6; 95% CI: 1.80−172.33; p = 0.01), thrombocytopenia <150,000/mm3 (OR: 18.6; 95% CI: 2.18−158.87; p < 0.01), and the presence of previous thrombotic events (OR: 6.1 for each event; 95% CI: 1.23−30.52; p = 0.03).

Univariate or multivariate analysis of factors associated with the diagnosis of APS or triple antibody positivity.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p |

| Female gender | 0.66 (0.19−2.29) | 0.52 | – | – |

| Age over 50 years | 0.38 (0.11−1.30) | 0.12 | – | – |

| History of abortions | 2.79 (0.5414.39) | 0.22 | – | – |

| ANA positivity | 2.80 (1.008−7.77) | 0.48 | – | – |

| OCC | 0.52 (0.25−1.08) | 0.82 | – | – |

| Number of synchronous thrombi | 0.50 (0.10−2.37) | 0.38 | – | – |

| History of autoimmune disease | 9.74 (2.55−37.13) | 0.01 | 12.08 (1.47−99.00) | 0.02 |

| PTT prolongation | 1.15 (1.05−1.26) | 0.02 | 17.64 (1.80−172.33) | 0.01 |

| Thrombocytopeniaa | 10.00 (2.68−37.23) | 0.01 | 18.61 (2.18−158.87) | 0.01 |

| Previous events | 8.28 (2.3−29.83) | 0.01 | 6.13 (1.23−30.52) | 0.03 |

ACO: oral contraceptives.

AIC for this model: 39.69; R2: 0.568.

The current study found that the likelihood of confirming an APS diagnosis is higher in patients with a history of autoimmune disease, a prolonged PTT greater than 5 seconds, thrombocytopenia, and previous thrombotic events. However, variables such as age under 50 years, thrombosis at unusual sites, and pregnancy-related morbidity were not significantly associated.

The authors of the modified Sapporo classification criteria suggest that strict exclusion criteria for APS workup are impractical, as multiple risk factors may converge in a single patient.6 The ISTH, based on evidence from previous recommendations and other guidelines, advocates for testing antiphospholipid antibodies to assess the risk profile in patients suspected of having APS.10 This includes patients with (1) age under 50 years with stroke or TIA; 2) unprovoked thromboembolic events or arterial thrombosis; (3) thrombosis at an unusual site; (4) microvascular thrombosis; (5) recurrent venous thrombosis not explained by anticoagulation, nonadherence, or malignancy; and (6) pregnancy morbidity that meets Sapporo criteria.

The BSH guidelines,3 based on indirect evidence due to the limitations of the studies used, recommend testing for antibodies in the following situations: (1) seven days after completing anticoagulant treatment for unprovoked venous thrombosis, or (2) young adults (<50 years) with an ischemic cerebrovascular event.

Our study reinforces the importance of certain factors in this list, such as unprovoked prior events, but does not find an independent association with others, like age. This difference is likely explained by age being a confounding factor, where the association is influenced by the presence of other autoimmune diseases, which tend to occur more frequently in younger individuals.

The documented association between autoimmune disease and APS was expected. APS is often linked with several autoimmune conditions, as shown in a follow-up cohort of 1,000 APS patients, where associations were found with lupus (36.2%), Sjögren's syndrome (2.2%), and rheumatoid arthritis (1.8%).15 In a cohort of 128 APS patients, 8% developed lupus after 8 years.16

The role of platelets in APS is well established and central to its pathogenesis.17 The most likely explanation for thrombocytopenia is consumption due to thrombosis, which aligns with the strong association we found between APS and platelet counts <150,000/mm3. The frequency of thrombocytopenia was estimated in a literature review of 1,455 subjects, with a prevalence of 25%.18 This article suggests that thrombocytopenia may be a prognostic factor. During the development of this research, new APS classification criteria were proposed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and EULAR.19 These guidelines also recognize thrombocytopenia as a diagnostic factor for APS, even including it as a new clinical domain that can contribute points to classification.19

Unlike our study, other previous cohorts, such as those by Cervera et al.,15 the international APS ACTION clinical repository and database, and the largest Colombian APS cohort by Díaz et al.,20 did not find a significant prevalence of prolonged PTT. However, the new ACR and EULAR 2023 guidelines19 recognize the importance of lupus anticoagulant in diagnosing APS, especially when persistently positive. Lupus anticoagulant is studied through PTT prolongation, which paradoxically occurs in APS, a procoagulant condition. This happens because PTT assays are dependent on phospholipid-based anticoagulation, and when antibodies against phospholipids are present, coagulation time is prolonged. Initially, two studies should be used to reduce false positives, one of which is PTT. Our results suggest that a prolonged PTT should be considered a pretest factor that indicates a high risk of a confirmed APS diagnosis following the full diagnostic process.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that when evaluating a patient with venous or arterial thrombosis, special attention should be given to the history of autoimmune disease, thrombocytopenia, prior thrombotic events, and prolonged PTT without an apparent cause. The presence of one or more of these factors should increase suspicion of APS and prompt testing for antiphospholipid antibodies to confirm the diagnosis.

Our population was relatively small compared to patients with secondary APS, so a comparison between the two groups was not conducted. However, the literature does not show significant differences between these two populations.21

There is limited literature comparing groups of subjects who meet the modified Sapporo criteria for APS with those who do not. A Canadian study22 included individuals aged 18 to 50 years with an unprovoked venous event. Of these, 491 were studied for APS, and 44 met the Sapporo classification criteria. In 59.1% of cases, one of the three tests was positive; 25% had two positive tests, and 15.9% were triple-positive. No differences were found between the two groups of APS patients—those who met the modified Sapporo criteria and those who did not—in terms of gender, previous history of arterial events, deep vein thrombosis, or pulmonary thromboembolism. Age was not a differentiating factor in their study. The only difference was the proportion of oral contraceptive use. These findings are like those observed in our population.

Regarding APS screening, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) pulmonary embolism surveillance guidelines9 propose limiting APS screening to patients with unprovoked pulmonary embolism who have risk factors for APS. Twelve of the 16- panel members recommended screening patients with unprovoked pulmonary embolism for APS if they have a history of arterial disease, microvascular thrombosis, thrombosis at unusual sites, pregnancy complications such as recurrent spontaneous abortions or preeclampsia/eclampsia, autoimmune diseases, younger age (<50 years), or unexplained prolonged activated PTT before treatment. However, it is important to note that the decision on which individuals to classify as at risk was divided among the panel members, due to the lack of strong evidence supporting one approach over another. Our data support some of these factors, such as prolonged PTT, autoimmune disease, and previous thrombotic events. Further studies are needed to determine whether systematic testing for APS should be considered in other cases, such as a history of obstetric complications or age <50 years.

The main limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size, which reduces the precision of the results. It is possible that with a larger sample size, other variables, such as age and thrombus location, could be associated with the diagnosis, although likely with less strength than the variables presented here. To better define the independent impact of each variable, multicenter studies with larger sample sizes should be conducted. Such studies could eventually help create a scale to discriminate between patients with a low or high risk of APS, which would be of significant clinical utility.

Another limitation of this study is that the tests were performed after the diagnosis of thrombosis, with the corresponding initiation of anticoagulation. This could introduce bias, as tests were conducted after the start of anticoagulation, and it was not possible to confirm the diagnosis with tests taken 12 weeks later in some patients with negative results. However, the approach taken reflects real-life practice, considering the risks associated with suspending anticoagulation during the acute phase to conduct tests or waiting 12 weeks for confirmatory testing.

It should also be noted that, in some cases, obstetric history was not clearly documented as it was not included in the medical records. While the missing information was limited, the research team chose not to report such history to avoid potential bias in the results.

Another limitation of our study is that it was not possible to determine whether the same factors identified can predict a diagnosis of APS according to the new criteria recently proposed by the ACR and EULAR in 2023. Our retrospective methodology prevents this analysis, as these new criteria incorporate additional clinical domains, such as the presence of livedo racemosa or lesions of livedoid vasculopathy on physical examination, as well as the documentation of complications like pulmonary hemorrhage, adrenal hemorrhage, myocardial disease, or cardiac valvular involvement. These domains have not been systematically recorded in the clinical records across multiple institutions, including ours, to date. New prospective studies assessing these domains will be required to confirm our findings considering the new 2023 criteria.

Finally, the number of subjects with arterial thrombosis was minimal, limiting the external validity of our findings in this population. Additional studies in individuals with arterial thrombosis as a clinical manifestation will be necessary to validate our results. Furthermore, some individuals diagnosed with APS may have been excluded because tests were not requested when the treating physician did not suspect the disease.

In conclusion, the likelihood of confirming the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome is higher in individuals with a history of autoimmune disease, PTT prolongation greater than five seconds, thrombocytopenia, and previous thrombotic events. In these cases, it is strongly recommended to request antiphospholipid syndrome antibodies. Following this recommendation could enhance diagnostic accuracy, increase disease confirmation rates, and optimize resource utilization.

Authors' contributionJaime Escobar and Oscar Muñoz: Conception and design of the study, or data acquisition, or analysis and interpretation of the data, draft of the article or critical review of the intellectual content, final approval of the version that was submitted.

Paula Ruiz Talero and Daniel Fernández: Draft of the article or critical review of the intellectual content, final approval of the version that was submitted.

FinancingFunding was provided by the San Ignacio University Hospital and the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (Bogotá, Colombia).