The number of clinical practice guidelines (CPG) to help in making clinical decisions is increasing. However, there is currently a lack of CPG for obsessive–compulsive disorder that take into account the requirements and expectations of the patients.

ObjectiveThe aim of the present study was to determine whether recommendations of the NICE guideline, “obsessive–compulsive disorder: core interventions in the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder” agrees with the needs and preferences of patients diagnosed with OCD in the mental health service.

Material and methodTwo focal groups were formed with a total of 12 participants. They were asked about the impact of the disorder in their lives, their experiences with the mental health services, their satisfaction with treatments, and about their psychological resources. Preferences and needs were compared with the recommendations of the guidelines, and to facilitate their analysis, they were classified into four topics: information, accessibility, treatments, and therapeutic relationship.

ResultsThe results showed a high agreement between recommendations and patients preferences, particularly as regards high-intensity psychological interventions. Some discrepancies included the lack of prior low-intensity psychological interventions in mental health service, and the difficulty of rapid access the professionals.

ConclusionsThere is significant concordance between recommendations and patients preferences and demands, which are only partially responded to by the health services.

Para facilitar la toma de decisiones clínicas, están proliferando las guías de práctica clínica (GPC). Sin embargo, actualmente se carece de GPC para el trastorno obsesivo compulsivo (TOC) en las que se incluyan los requerimientos y las expectativas de los usuarios.

ObjetivosEl objetivo del presente trabajo es conocer si las recomendaciones de la guía «Obsessive-compulsive disorder: core interventions in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder» del National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) se corresponden con las necesidades y preferencias de un grupo de usuarios diagnosticados de TOC.

MétodosPara ello, se conformaron 2 grupos focales con un total de 12 pacientes, a los que se preguntó sobre el impacto del TOC en sus vidas, su experiencia con los servicios de salud mental, la satisfacción con los tratamientos recibidos y los recursos personales de afrontamiento. Las preferencias y necesidades de los usuarios se compararon con las recomendaciones de la guía y, para facilitar su accesibilidad, se agruparon en 4 grandes áreas temáticas: información, accesibilidad, abordaje terapéutico y relación terapéutica.

ResultadosSe observó una alta correspondencia entre las recomendaciones y las preferencias de los usuarios; por ejemplo, respecto a las intervenciones psicológicas de alta intensidad. La escasez de intervenciones psicológicas de baja intensidad antes de acudir al servicio de salud mental o la dificultad para acceder a los profesionales son algunas de las experiencias narradas que discreparon con las recomendaciones de la guía y de las necesidades expresadas por este grupo de usuarios.

ConclusionesHay coincidencia entre las recomendaciones y las preferencias y necesidades de los usuarios; sin embargo, los servicios sanitarios responden a ellas parcialmente.

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is mainly characterised by two elements. One is obsessions, recurrent and persistent thoughts or images that trigger intensely distressing feelings; the other is compulsions, defined as the different types of behaviour an individual engages in to attempt to get rid of or neutralise the obsessions. These obsessions and compulsions also greatly interfere in more than one area of the person's life.1

The prevalence of OCD ranges from 1% to 2% of the population, and does not vary greatly from country to country.2,3 Onset is usually before the age of 25, generally in preadolescence.4

There are a number of difficulties in the approach to OCD. One is the variable nature of the symptoms from one person to another, making diagnosis difficult for primary care physicians. The person may also have comorbid conditions that very often mask the main problem.3 Moreover, it is common for sufferers to be embarrassed by their symptoms and they tend to hide it from people around them.5,6 All this contributes to a delay in diagnosis, with the consequent increase in the severity of the person's condition. It is therefore not surprising that OCD is considered as one of the potentially most debilitating mental disorders.

For OCD and other health problems which, because of their severity or prevalence require a more specific approach, the scientific healthcare community prepares clinical practice guidelines (CPG). Among other aspects, the CPGs include series of recommendations based on the available empirical evidence. To ensure that healthcare professionals and users follow and accept the recommendations, in the last 20 years there has been growing interest in encouraging the participation of users who suffer from the clinical problem in the preparation of the guidelines.7,8 The participation of users in the design of health services for chronic problems can make a key contribution, as it provides information on which aspects are essential for understanding new mechanisms to reduce complexity or strengthen the involvement of patients in looking after their own health.9,10 In fact, nowadays the quality and rigour of a set of guidelines are also measured according to who participated in their preparation.11 With that in mind, the working group for this study developed a set of CPGs, in this case aimed at generalised anxiety disorder, in which we introduced the novelty of linking the guideline recommendations with testimonials from patients, gathered in a qualitative study, about their experiences with the healthcare system.12 Other national health service mental health guidelines have also been put together involving patients.13

Up to now, user participation in the guidelines on OCD was either non-existent14,15 or minimal.5 The United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) CPG in particular includes a chapter with testimonials of people diagnosed with OCD. However, there is little association between these testimonials and the guideline's recommendations. In view of the complexity of the approach to OCD mentioned above and its importance in both social care and healthcare terms, it is vital for the users to be more involved in the preparation of CPGs.

The aim of this study was therefore to determine to what extent the recommendations included in the CPGs for OCD meet the needs and preferences of a group of users with this disorder.

MethodDesignWe carried out a qualitative descriptive study, with an eidetic phenomenological approach, followed by a panel of experts to adapt the results to the recommendations for a set of CPGs on OCD.

Context of the studyThe study was carried out in the El Limonar Community Mental Health Unit, part of the Clinical Management Unit for Mental Health of the Regional University Hospital of Malaga. This service routinely covers a population of 165,000 people, and provides psychiatric and psychological care to people with a range of mental illnesses, as well as group therapies specifically aimed at different psychopathological profiles. The unit looks after approximately 150 users each year diagnosed with OCD.

Study subjectsThe patients were selected taking into account the following inclusion criteria:

- •

Diagnosis of OCD according to the DSM-5.1

- •

Follow-up in the Community Mental Health Unit of at least 2 appointments. This criterion ensured that the user had sufficient experience in both primary care and mental health care to be able to comment on the issues raised.

The exclusion criteria were:

- •

Aged under 18.

- •

Diagnosis of a severe mental illness (psychotic or bipolar disorders) or a comorbid addiction (alcohol or any illegal drug).

- •

Intellectual disability, limiting intelligence quotient or significant functional deterioration.

- •

Having dropped out of healthcare follow-up without being discharged by a doctor.

- •

Marginal social situation or illiteracy.

Participants were included by purposive sampling from the complete list of users diagnosed with OCD. The computerised medical history of each user was reviewed, and those who met the inclusion criteria and did not meet the exclusion criteria were selected. Those selected were contacted by telephone, and they were asked to take part after having the purpose of the research explained to them. Those who agreed to take part were given appointments for the group interview. Before starting the interviews, participants were able to read the information sheet about the study and ask any questions they considered appropriate before signing the informed consent form. No other segmentation criteria were used for the groups.

The sample size was subjected to the information saturation principle during the data collection and analysis process.

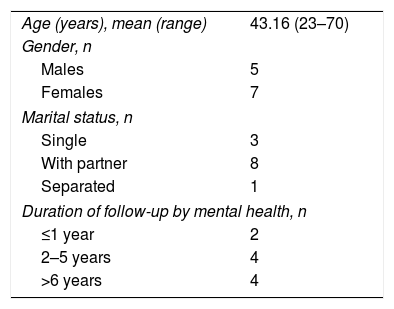

Lastly, the sample obtained consisted of 12 participants who agreed to take part in the research and attended the interview. Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the sample.

Data collectionThe technique used to obtain the data was the group interview using focus groups. Two group interviews were carried out conducted by a neutral moderator with experience in qualitative interviews, in the presence of an observer. They lasted from 90 to 120min.

The interview consisted of a script of open questions about personal and healthcare experience, based on aspects identified in the literature, interviews with experts and, in particular, on questions from the survey carried out by the group that developed the NICE guidelines for generalised anxiety disorder.12,16 The topics addressed were: impact of OCD on daily life and interpersonal relationships; rating of the professionals involved (primary care and mental health) and the care process; types of approaches offered in the public health system (psychological and pharmacological) and their perceived usefulness; and personal resources for coping with anxiety. The questions were of an open nature and the interview was conducted in a flexible style, in order that issues which were not initially proposed could emerge.

Data analysisThe sessions were recorded on audio, transcribed and incorporated into qualitative analysis software (ATLAS Ti 7.0). Content analysis was carried out according to the principles of Taylor and Bodgan.17

Emerging issues were identified after several successive readings of the interviews by three independent investigators. Subsequently, each of the investigators encoded the significant citations. The three investigators reviewed these codes jointly. The investigators then discussed discrepancies in the proposed codes until a final consensus was reached. The codes were grouped into categories and subcategories and analysed taking into account the potential influence deriving from the investigators.

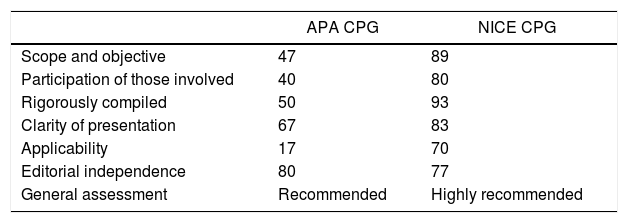

At the same time, a comprehensive literature search of the CPGs on OCD was carried out, and three were identified, those produced by NICE,5 the Psychiatric Association14 and the Canadian health service.15 The first two were subjected to the quality assessment; the third only had a very small section devoted to OCD as they are general guidelines for different anxiety disorders. The assessment was carried out by five independent experts using the instrument AGREE II. Lastly, the NICE5 guidelines were selected, as they obtained the best score (Table 2). After reviewing all the recommendations, the most significant of the different stages of healthcare were selected and placed in relation to the subject categories resulting from the qualitative analysis of the focus groups. These initial pairings were later distributed among six experts, who include three clinical psychologists, two psychiatrists and one nurse. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Percentage of the maximum possible score in each domain of the APA and NICE CPGs.

| APA CPG | NICE CPG | |

|---|---|---|

| Scope and objective | 47 | 89 |

| Participation of those involved | 40 | 80 |

| Rigorously compiled | 50 | 93 |

| Clarity of presentation | 67 | 83 |

| Applicability | 17 | 70 |

| Editorial independence | 80 | 77 |

| General assessment | Recommended | Highly recommended |

APA: American Psychiatric Association; NICE: National Institute for Clinical Excellence.

Note: score calculated according to the formula: [(score obtained−minimum score)/(maximum score−minimum score)]×100.

This procedure implies that not all user accounts were included as study results; only those related to the areas of uncertainty of the CPG were used.

Credibility and validityTo guarantee the credibility and validity of the results, the Lincoln and Guba18 criteria were taken into account: credibility, transferability, reliability and confirmability. To ensure credibility in the analysis process, we triangulated codes and categories. The transferability was reinforced by exhaustive collection of the data, detailed description of the participants and the amount of information collected in each group, such that we were able to guarantee that sufficient information was available. The criterion of consistency and repeatability of the data was monitored through a detailed and documented process of the analysis strategy, as well as the context in which the data collection took place.

From the point of view of the confirmability and degree of reflection before the beginning of the study, the researchers carried out an analysis of preconceived ideas and own expectations regarding the results of the study to enable them to later compare what influence they might have had during the course of the process. In addition, we used a neutral moderator/interviewer (not belonging to the research team) and experienced in qualitative interviews.

Ethical considerationsThe study was authorised by the Malaga Provincial Independent Ethics Committee. All participants were informed in writing and verbally in advance of the request for their consent to take part in the study. The Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revised versions and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines were adhered to at all times. The data were treated confidentially and rendered anonymous for processing during the analysis.

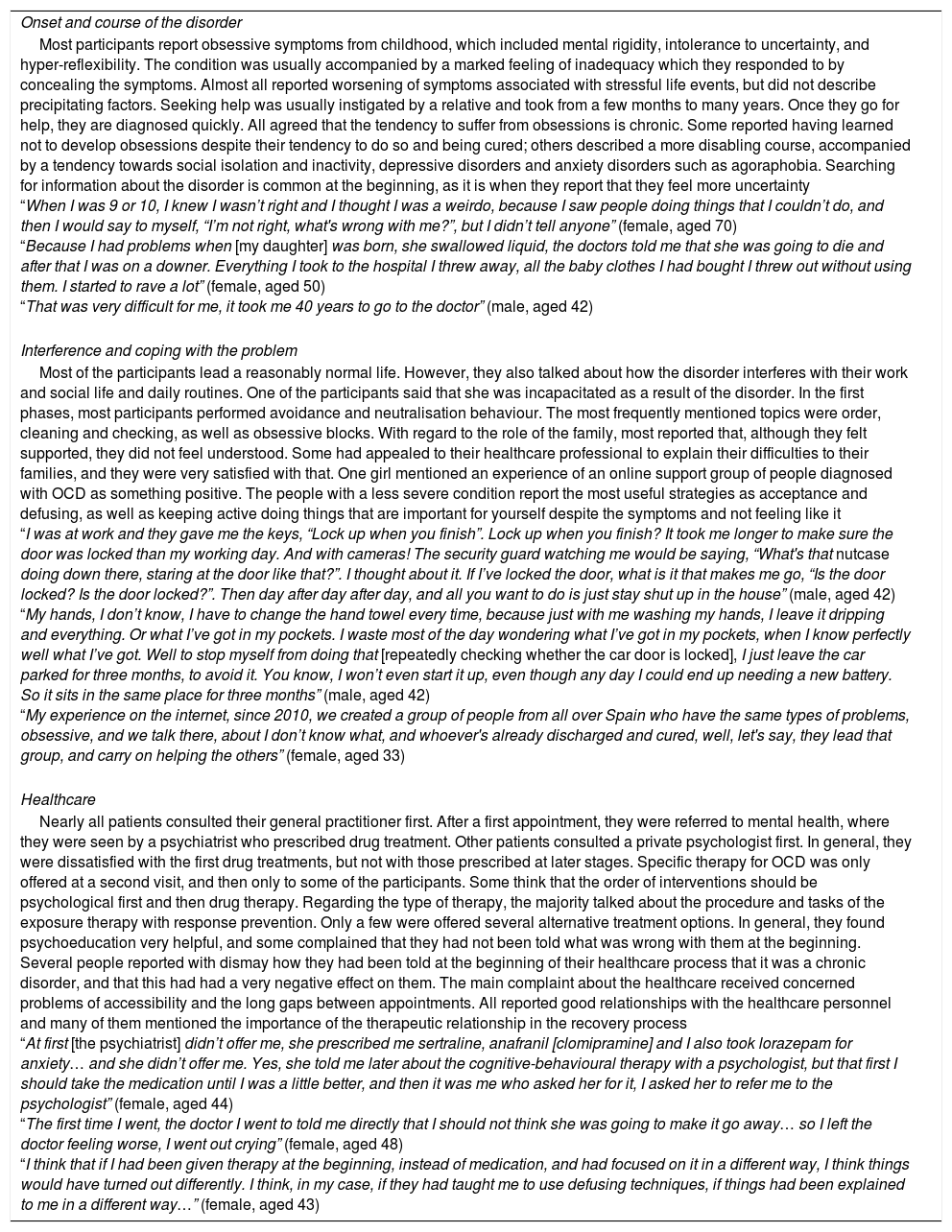

ResultsResults from the focus groupsAs a result of the qualitative analysis, three general categories were identified: (a) development of the disorder and seeking help; (b) interference and coping with the problem; and c) health care. Table 3 shows each of the categories with the information obtained, along with some related fragments from the participants’ comments.

Results by category and example fragments.

| Onset and course of the disorder |

| Most participants report obsessive symptoms from childhood, which included mental rigidity, intolerance to uncertainty, and hyper-reflexibility. The condition was usually accompanied by a marked feeling of inadequacy which they responded to by concealing the symptoms. Almost all reported worsening of symptoms associated with stressful life events, but did not describe precipitating factors. Seeking help was usually instigated by a relative and took from a few months to many years. Once they go for help, they are diagnosed quickly. All agreed that the tendency to suffer from obsessions is chronic. Some reported having learned not to develop obsessions despite their tendency to do so and being cured; others described a more disabling course, accompanied by a tendency towards social isolation and inactivity, depressive disorders and anxiety disorders such as agoraphobia. Searching for information about the disorder is common at the beginning, as it is when they report that they feel more uncertainty “When I was 9 or 10, I knew I wasn’t right and I thought I was a weirdo, because I saw people doing things that I couldn’t do, and then I would say to myself, “I’m not right, what's wrong with me?”, but I didn’t tell anyone” (female, aged 70) “Because I had problems when [my daughter] was born, she swallowed liquid, the doctors told me that she was going to die and after that I was on a downer. Everything I took to the hospital I threw away, all the baby clothes I had bought I threw out without using them. I started to rave a lot” (female, aged 50) “That was very difficult for me, it took me 40 years to go to the doctor” (male, aged 42) |

| Interference and coping with the problem |

| Most of the participants lead a reasonably normal life. However, they also talked about how the disorder interferes with their work and social life and daily routines. One of the participants said that she was incapacitated as a result of the disorder. In the first phases, most participants performed avoidance and neutralisation behaviour. The most frequently mentioned topics were order, cleaning and checking, as well as obsessive blocks. With regard to the role of the family, most reported that, although they felt supported, they did not feel understood. Some had appealed to their healthcare professional to explain their difficulties to their families, and they were very satisfied with that. One girl mentioned an experience of an online support group of people diagnosed with OCD as something positive. The people with a less severe condition report the most useful strategies as acceptance and defusing, as well as keeping active doing things that are important for yourself despite the symptoms and not feeling like it “I was at work and they gave me the keys, “Lock up when you finish”. Lock up when you finish? It took me longer to make sure the door was locked than my working day. And with cameras! The security guard watching me would be saying, “What's that nutcase doing down there, staring at the door like that?”. I thought about it. If I’ve locked the door, what is it that makes me go, “Is the door locked? Is the door locked?”. Then day after day after day, and all you want to do is just stay shut up in the house” (male, aged 42) “My hands, I don’t know, I have to change the hand towel every time, because just with me washing my hands, I leave it dripping and everything. Or what I’ve got in my pockets. I waste most of the day wondering what I’ve got in my pockets, when I know perfectly well what I’ve got. Well to stop myself from doing that [repeatedly checking whether the car door is locked], I just leave the car parked for three months, to avoid it. You know, I won’t even start it up, even though any day I could end up needing a new battery. So it sits in the same place for three months” (male, aged 42) “My experience on the internet, since 2010, we created a group of people from all over Spain who have the same types of problems, obsessive, and we talk there, about I don’t know what, and whoever's already discharged and cured, well, let's say, they lead that group, and carry on helping the others” (female, aged 33) |

| Healthcare |

| Nearly all patients consulted their general practitioner first. After a first appointment, they were referred to mental health, where they were seen by a psychiatrist who prescribed drug treatment. Other patients consulted a private psychologist first. In general, they were dissatisfied with the first drug treatments, but not with those prescribed at later stages. Specific therapy for OCD was only offered at a second visit, and then only to some of the participants. Some think that the order of interventions should be psychological first and then drug therapy. Regarding the type of therapy, the majority talked about the procedure and tasks of the exposure therapy with response prevention. Only a few were offered several alternative treatment options. In general, they found psychoeducation very helpful, and some complained that they had not been told what was wrong with them at the beginning. Several people reported with dismay how they had been told at the beginning of their healthcare process that it was a chronic disorder, and that this had had a very negative effect on them. The main complaint about the healthcare received concerned problems of accessibility and the long gaps between appointments. All reported good relationships with the healthcare personnel and many of them mentioned the importance of the therapeutic relationship in the recovery process “At first [the psychiatrist] didn’t offer me, she prescribed me sertraline, anafranil [clomipramine] and I also took lorazepam for anxiety… and she didn’t offer me. Yes, she told me later about the cognitive-behavioural therapy with a psychologist, but that first I should take the medication until I was a little better, and then it was me who asked her for it, I asked her to refer me to the psychologist” (female, aged 44) “The first time I went, the doctor I went to told me directly that I should not think she was going to make it go away… so I left the doctor feeling worse, I went out crying” (female, aged 48) “I think that if I had been given therapy at the beginning, instead of medication, and had focused on it in a different way, I think things would have turned out differently. I think, in my case, if they had taught me to use defusing techniques, if things had been explained to me in a different way…” (female, aged 43) |

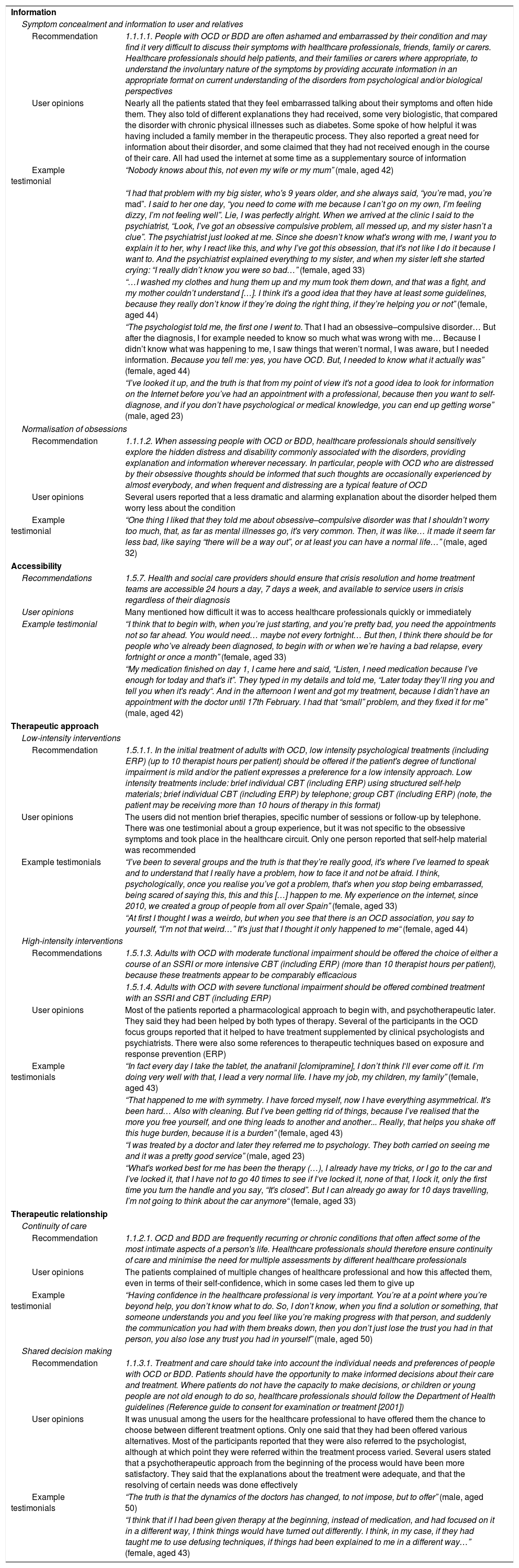

The recommendations that were linked to the preferences and needs of the users were grouped into four major subject areas, some divided into sub-areas: (a) information (concealment of symptoms and information to the user and family members, normalisation of obsessions); (b) accessibility; (c) therapeutic approach (low-intensity interventions, high-intensity interventions); and (d) therapeutic relationship (continuity of care, shared decision-making).

These subject areas form the structure for Table 4, where the CPG recommendations are shown along with a summary of user opinion concerning that area and an example testimonial. As the user testimonials do not include the fine points that differentiate some recommendations from others, we selected one or two of those that refer to the same aspects. Some recommendations have not been included, as the users did not comment on them.

Linking the NICE OCD guideline recommendations with user testimonials, classified by areas of uncertainty.

| Information | |

| Symptom concealment and information to user and relatives | |

| Recommendation | 1.1.1.1. People with OCD or BDD are often ashamed and embarrassed by their condition and may find it very difficult to discuss their symptoms with healthcare professionals, friends, family or carers. Healthcare professionals should help patients, and their families or carers where appropriate, to understand the involuntary nature of the symptoms by providing accurate information in an appropriate format on current understanding of the disorders from psychological and/or biological perspectives |

| User opinions | Nearly all the patients stated that they feel embarrassed talking about their symptoms and often hide them. They also told of different explanations they had received, some very biologistic, that compared the disorder with chronic physical illnesses such as diabetes. Some spoke of how helpful it was having included a family member in the therapeutic process. They also reported a great need for information about their disorder, and some claimed that they had not received enough in the course of their care. All had used the internet at some time as a supplementary source of information |

| Example testimonial | “Nobody knows about this, not even my wife or my mum” (male, aged 42) |

| “I had that problem with my big sister, who's 9 years older, and she always said, “you’re mad, you’re mad”. I said to her one day, “you need to come with me because I can’t go on my own, I’m feeling dizzy, I’m not feeling well”. Lie, I was perfectly alright. When we arrived at the clinic I said to the psychiatrist, “Look, I’ve got an obsessive compulsive problem, all messed up, and my sister hasn’t a clue”. The psychiatrist just looked at me. Since she doesn’t know what's wrong with me, I want you to explain it to her, why I react like this, and why I’ve got this obsession, that it's not like I do it because I want to. And the psychiatrist explained everything to my sister, and when my sister left she started crying: “I really didn’t know you were so bad…” (female, aged 33) | |

| “…I washed my clothes and hung them up and my mum took them down, and that was a fight, and my mother couldn’t understand […]. I think it's a good idea that they have at least some guidelines, because they really don’t know if they’re doing the right thing, if they’re helping you or not” (female, aged 44) | |

| “The psychologist told me, the first one I went to. That I had an obsessive–compulsive disorder… But after the diagnosis, I for example needed to know so much what was wrong with me… Because I didn’t know what was happening to me, I saw things that weren’t normal, I was aware, but I needed information. Because you tell me: yes, you have OCD. But, I needed to know what it actually was” (female, aged 44) | |

| “I’ve looked it up, and the truth is that from my point of view it's not a good idea to look for information on the Internet before you’ve had an appointment with a professional, because then you want to self-diagnose, and if you don’t have psychological or medical knowledge, you can end up getting worse” (male, aged 23) | |

| Normalisation of obsessions | |

| Recommendation | 1.1.1.2. When assessing people with OCD or BDD, healthcare professionals should sensitively explore the hidden distress and disability commonly associated with the disorders, providing explanation and information wherever necessary. In particular, people with OCD who are distressed by their obsessive thoughts should be informed that such thoughts are occasionally experienced by almost everybody, and when frequent and distressing are a typical feature of OCD |

| User opinions | Several users reported that a less dramatic and alarming explanation about the disorder helped them worry less about the condition |

| Example testimonial | “One thing I liked that they told me about obsessive–compulsive disorder was that I shouldn’t worry too much, that, as far as mental illnesses go, it's very common. Then, it was like… it made it seem far less bad, like saying “there will be a way out”, or at least you can have a normal life…” (male, aged 32) |

| Accessibility | |

| Recommendations | 1.5.7. Health and social care providers should ensure that crisis resolution and home treatment teams are accessible 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and available to service users in crisis regardless of their diagnosis |

| User opinions | Many mentioned how difficult it was to access healthcare professionals quickly or immediately |

| Example testimonial | “I think that to begin with, when you’re just starting, and you’re pretty bad, you need the appointments not so far ahead. You would need… maybe not every fortnight… But then, I think there should be for people who’ve already been diagnosed, to begin with or when we’re having a bad relapse, every fortnight or once a month” (female, aged 33) |

| “My medication finished on day 1, I came here and said, “Listen, I need medication because I’ve enough for today and that's it”. They typed in my details and told me, “Later today they’ll ring you and tell you when it's ready“. And in the afternoon I went and got my treatment, because I didn’t have an appointment with the doctor until 17th February. I had that “small” problem, and they fixed it for me” (male, aged 42) | |

| Therapeutic approach | |

| Low-intensity interventions | |

| Recommendation | 1.5.1.1. In the initial treatment of adults with OCD, low intensity psychological treatments (including ERP) (up to 10 therapist hours per patient) should be offered if the patient's degree of functional impairment is mild and/or the patient expresses a preference for a low intensity approach. Low intensity treatments include: brief individual CBT (including ERP) using structured self-help materials; brief individual CBT (including ERP) by telephone; group CBT (including ERP) (note, the patient may be receiving more than 10 hours of therapy in this format) |

| User opinions | The users did not mention brief therapies, specific number of sessions or follow-up by telephone. There was one testimonial about a group experience, but it was not specific to the obsessive symptoms and took place in the healthcare circuit. Only one person reported that self-help material was recommended |

| Example testimonials | “I’ve been to several groups and the truth is that they’re really good, it's where I’ve learned to speak and to understand that I really have a problem, how to face it and not be afraid. I think, psychologically, once you realise you’ve got a problem, that's when you stop being embarrassed, being scared of saying this, this and this […] happen to me. My experience on the internet, since 2010, we created a group of people from all over Spain” (female, aged 33) |

| “At first I thought I was a weirdo, but when you see that there is an OCD association, you say to yourself, “I’m not that weird…” It's just that I thought it only happened to me“ (female, aged 44) | |

| High-intensity interventions | |

| Recommendations | 1.5.1.3. Adults with OCD with moderate functional impairment should be offered the choice of either a course of an SSRI or more intensive CBT (including ERP) (more than 10 therapist hours per patient), because these treatments appear to be comparably efficacious |

| 1.5.1.4. Adults with OCD with severe functional impairment should be offered combined treatment with an SSRI and CBT (including ERP) | |

| User opinions | Most of the patients reported a pharmacological approach to begin with, and psychotherapeutic later. They said they had been helped by both types of therapy. Several of the participants in the OCD focus groups reported that it helped to have treatment supplemented by clinical psychologists and psychiatrists. There were also some references to therapeutic techniques based on exposure and response prevention (ERP) |

| Example testimonials | “In fact every day I take the tablet, the anafranil [clomipramine], I don’t think I‘ll ever come off it. I’m doing very well with that, I lead a very normal life. I have my job, my children, my family” (female, aged 43) |

| “That happened to me with symmetry. I have forced myself, now I have everything asymmetrical. It's been hard… Also with cleaning. But I’ve been getting rid of things, because I’ve realised that the more you free yourself, and one thing leads to another and another... Really, that helps you shake off this huge burden, because it is a burden” (female, aged 43) | |

| “I was treated by a doctor and later they referred me to psychology. They both carried on seeing me and it was a pretty good service” (male, aged 23) | |

| “What's worked best for me has been the therapy (…), I already have my tricks, or I go to the car and I’ve locked it, that I have not to go 40 times to see if I‘ve locked it, none of that, I lock it, only the first time you turn the handle and you say, “It's closed”. But I can already go away for 10 days travelling, I’m not going to think about the car anymore“ (female, aged 33) | |

| Therapeutic relationship | |

| Continuity of care | |

| Recommendation | 1.1.2.1. OCD and BDD are frequently recurring or chronic conditions that often affect some of the most intimate aspects of a person's life. Healthcare professionals should therefore ensure continuity of care and minimise the need for multiple assessments by different healthcare professionals |

| User opinions | The patients complained of multiple changes of healthcare professional and how this affected them, even in terms of their self-confidence, which in some cases led them to give up |

| Example testimonial | “Having confidence in the healthcare professional is very important. You’re at a point where you’re beyond help, you don’t know what to do. So, I don’t know, when you find a solution or something, that someone understands you and you feel like you’re making progress with that person, and suddenly the communication you had with them breaks down, then you don’t just lose the trust you had in that person, you also lose any trust you had in yourself” (male, aged 50) |

| Shared decision making | |

| Recommendation | 1.1.3.1. Treatment and care should take into account the individual needs and preferences of people with OCD or BDD. Patients should have the opportunity to make informed decisions about their care and treatment. Where patients do not have the capacity to make decisions, or children or young people are not old enough to do so, healthcare professionals should follow the Department of Health guidelines (Reference guide to consent for examination or treatment [2001]) |

| User opinions | It was unusual among the users for the healthcare professional to have offered them the chance to choose between different treatment options. Only one said that they had been offered various alternatives. Most of the participants reported that they were also referred to the psychologist, although at which point they were referred within the treatment process varied. Several users stated that a psychotherapeutic approach from the beginning of the process would have been more satisfactory. They said that the explanations about the treatment were adequate, and that the resolving of certain needs was done effectively |

| Example testimonials | “The truth is that the dynamics of the doctors has changed, to not impose, but to offer” (male, aged 50) |

| “I think that if I had been given therapy at the beginning, instead of medication, and had focused on it in a different way, I think things would have turned out differently. I think, in my case, if they had taught me to use defusing techniques, if things had been explained to me in a different way…” (female, aged 43) | |

The aim of this study was to determine to what extent the recommendations in the NICE OCD guidelines are adapted to the preferences and experiences of a group of users with this disorder. Seeking such a connection between the evidence-based recommendations and the experiences reported by the users is a novel approach compared to how the most important clinical practice guidelines were put together in the past. The research team in this study has used the same method in the Spanish adaptation of the NICE guidelines on generalised anxiety disorder.12 In general, it can be said that there is a high degree of agreement between the recommendations and the preferences of the users, particularly with regard to high-intensity interventions. However, some experiences reported by many users do not correspond with the recommendations and do not therefore meet their preferences, particularly concerning healthcare professional accessibility, healthcare professional continuity, the information received about the diagnosis and the offer of psychological interventions. Some of these discrepancies concerned the scarcity of low-intensity interventions before being referred to the mental health services, the little, or zero, involvement of users in decision-making, and the difficulty in obtaining quick or immediate access to healthcare professionals.

This study is responding to the need to take into account the experiences of users when establishing clinical practice recommendations. Many authors and movements already advocate this idea. The empowerment of patients and the implementation of shared decision-making, very much in line with the recovery model and democratic participation, are some of the advantages of this involvement.19 Some authors report that, in the case of mental health, the involvement of users becomes more helpful, as the costs and benefits of both drug treatments and psychological interventions are not so clear.19 However, other authors, although agreeing that guidelines should be focused on the users, advocate caution in this area, arguing that there is still not enough evidence that user involvement improves the quality of the CPG8,20 and that more implementation studies are needed on CPGs prepared with wider user participation, to provide evidence over the next few years. A study was published recently showing the four-year impact of the involvement of users in the development of a Norwegian mental health service on professional practices, in terms of providing information to users and family members, and the professionals’ knowledge about user participation and involvement. The results also show that the changes in the professionals occurred in the long term, while no changes were detected in the short term; an aspect of crucial importance when evaluating this type of strategy.21

There is also no consensus on how to involve the users, although some procedures and experiences have been published.13 Among the disadvantages of involving users in guideline development are that they can become very individualised, as preferences vary from one user to another, or that users’ limited knowledge of medical terminology or concepts such as cost-effectiveness can obstruct the objectives of the guideline.8

Although nowadays most CPGs are developed using the GRADE methodology, which includes the participation of patients in the assessment of the clinical significance of the results22 and in the grading of the strength of the recommendations,23 studies indicate that patients feel “uncomfortable” with the formal structure of the development of CPGs and even that patients who acquire competence in these aspects lose “credibility” in terms of their condition as “real” patients.24

With respect to the approach, little mention was made by the users who took part in low-intensity interventions. In contrast, recommendations about high-intensity interventions seemed to coincide with the experiences of most users. This approach is placed in the context of the step-by-step model of care, which aims to offer the user the least intrusive effective intervention for the problem he/she has. Low-intensity treatments should therefore be offered before others that require greater intervention by the healthcare professional.25 This model, the main aims of which are “demedicalisation” and “depsychologisation”, comes from the British health service, and introduction in other countries such as Spain is relatively recent, so it is only to be expected that interventions of this type are not yet fully implemented in the Spanish national health system.

As far as the accessibility of healthcare professionals was concerned, the majority reported some discontent and wished to be seen more quickly by a service more adaptable to dealing with exacerbations of their OCD symptoms. Another complaint from the patients was about the frequent changes of healthcare professionals, and highlighting the importance of the therapeutic relationship. In a previous qualitative study, it was also found that the patients themselves underlined the therapeutic relationship as one of the most helpful treatment elements and pointed out the motivating role and the support that the healthcare professionals provide in the therapeutic process.26 This aspect essentially has to be guaranteed by the organisational systems of the health services, as meeting this need is beyond the control of the clinician.

With regard to shared decision-making, that type of user experience is rare, especially with respect to the offer of psychological interventions. Previous studies also show that users prefer to be referred to mental health services, and specifically to clinical psychologists27 and for psychological interventions28; they also show a preference for the options with which users have had previous experience.29 Most state that the initial approach was pharmacological. Some users did acknowledge a certain tendency of healthcare professionals to make the patient a participant in decision-making regarding therapeutic options.

All the patients expressed feelings of embarrassment about their symptoms and about hiding them. The stigma suffered by these people has been illustrated in a number of studies.6 Interventions such as defusing techniques, rated as very useful by many of the participants in this study, can help to reduce concealment and shame and, consequently, also improve their interpersonal relationships. With regard to family relationships, the participants rated healthcare professionals informing family members of their difficulties very positively. Previous studies also show that family relationships improved after knowing about the condition.6

The search for information on the internet about the disorder, which in many cases responds to the need to know more about it, was also a rule in this group of patients. Most patients were also given an explanation about what was wrong with them, although in different terms, with some more biologistic and others more behavioural. Adequate psychoeducation of patients about what is happening to them enables them to generate coping strategies more adapted to their difficulty, and that helps them feel more empowered.

The NICE OCD guidelines do not link the recommendations with the preferences and needs of the users, but they do use extracts about certain needs from the testimonials of some users. There is a high degree of concordance between those indicated in the NICE guidelines and those identified in this study. Specifically, both groups of users attach great importance to the therapeutic relationship that advocates a climate of respect and trust towards the patient with OCD and access to treatment and shared decision-making. The users of the NICE guidelines also point out other aspects not mentioned by the participants of this study, such as self-help groups and group therapies specific to OCD, as well as a greater awareness of the population of the disorder.

Regarding the limitations of the study, it is worth noting that it was conducted on an existing CPG, meaning that the users did not participate in the conception, the definition of areas of uncertainty, the objectives, the recommendations, etc. Their participation was limited to comparing the perceptions and experiences of health service users with recommendations from a set of CPGs. Another limitation concerns self-bias. The decision to participate could have been influenced by their satisfaction with the health service and by the severity of the symptoms at the time their participation was requested.

ConclusionsTaking into account the opinion of the users when organising services may encourage the healthcare professionals to follow the recommendations. In the approach to a problem as complex as OCD, the fact that the recommendations include the preferences and needs of users could improve adherence to and, as a consequence, the efficacy and effectiveness of the interventions. In this study, the NICE guidelines were selected to determine whether or not the preferences and experiences of a group of users of mental health services coincide with the recommendations they contain. A high degree of correspondence was found between the recommendations and the preferences. However, some experiences reported do not correspond with the recommendations and do not therefore meet their preferences, particularly concerning healthcare professional accessibility, healthcare professional continuity, the information given about the diagnosis and the offer of psychological treatment.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Villena-Jimena A, Gómez-Ocaña C, Amor-Mercado G, Núñez-Vega A, Morales-Asencio JM, Hurtado MM. ¿En qué medida las guías de práctica clínica responden a las necesidades y preferencias de los usuarios diagnosticados de trastorno obsesivo compulsivo? Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2018;47:98–107.