There are not many studies on prevalence and factors (use of social networks, for example) associated with eating disorders (ED) in Colombia. These types of studies in regular female gym-goers are of particular interest.

MethodsThe objective was to analyse the relationship between the risk of EDs and the use of social networks in 337 women between the ages of 15 and 30 who had been regularly going to the gym in the city of Medellín for four months or more. The type of study was quantitative, descriptive and cross-sectional.

ResultsA total of 143 (47.5%) cases with a risk of EDs were identified. Statistically significant associations were found between the risk of eating disorders and some aspects of the use of social networks.

DiscussionThe possible association between ED, the use of social networks and certain personality characteristics and sociocultural beauty stereotypes are discussed.

ConclusionsThe findings point to an association between the use of social networks as a way to achieve self-image approval, abnormal eating attitudes and body satisfaction. This behaviour, added to other vulnerability factors, may increase the risk for the initiation or maintenance of an ED, particularly in the population using gyms and physical conditioning centres.

No son muchos los estudios sobre la prevalencia y los factores asociados (p. ej., uso de redes sociales) con los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria (TCA) en Colombia. De particular interés son este tipo de estudios en población femenina que asiste regularmente a gimnasios.

MétodosEl objetivo es analizar la relación entre el riesgo de TCA y el uso de redes sociales en 337 mujeres con edades entre los 15 y los 30 años que llevaban más de 4 meses asistiendo regularmente a gimnasios de la ciudad de Medellín, mediante un estudio cuantitativo descriptivo de corte transversal.

ResultadosSe identificaron 143 (47,5%) casos con riesgo de TCA. Se encontraron asociaciones estadísticamente significativas entre el riesgo de TCA y algunos aspectos del uso de redes sociales.

DiscusiónSe discute la posible asociación entre el TCA, el uso de redes sociales y ciertas características de personalidad y los estereotipos socioculturales de belleza.

ConclusionesLos hallazgos señalan una asociación entre el uso de redes sociales como modo de lograr la aprobación de la autoimagen, las actitudes alimentarias anómalas y la satisfacción corporal. Este comportamiento, sumado a otros factores de vulnerabilidad, puede aumentar el riesgo de que se inicie o se mantenga un TCA, particularmente en población que hace uso de gimnasios y centros para al acondicionamiento físico.

Eating disorders (EDs) are characterised by a persistent abnormality in eating or eating-related behaviour that causes a significant decline in physical health and/or psychosocial functioning.1 Global epidemiological data have reported that, among these disorders, bingeing, bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa are the most prevalent.2 A recent study on the global burden of these disorders revealed their significance due to the impact that they are having, especially in females 15–19 years of age.3 Latin America, compared to eastern Europe and the United States, has a lower prevalence of anorexia but higher prevalences of bulimia and bingeing.4

Several studies on EDs have been conducted in Colombia. Piñeros et al.5 reported a risk prevalence of 15%, predominantly in females, in a sample of students 12–20 years of age in Bogotá. A study by Ángel et al.,6 with university students from the same city, reported that 30.7% of their sample was at risk of suffering from an ED, with a higher percentage in females. In Bucaramanga, Rueda et al.7 recorded a prevalence of 29.9% in a sample of adolescents aged 10–19 in school. Also in Bucaramanga, but in a sample of university students aged 17–25, Rueda et al.8 reported a risk prevalence of 38.7%. According to Rueda et al.,7 females 18–29 years of age represent the population segment at highest risk of EDs.

Several factors have been proposed as causes of EDs:9,10 sociocultural factors (cultures in which food is abundant, communication media, peer influence and idealisation of thinness), family factors (complicated, intrusive and hostile families who deny the person’s emotional needs; coercive parental control, families with a history of physical or sexual abuse; and other considerations related to family dynamics and the relationship between parents and children) and individual factors (personality traits, deficient self-esteem, abuse in childhood, emotional disturbances, identity problems, dissatisfaction with one's own body, obsessions, perfectionism, cognitive bias, genetic influences and neuroendocrine abnormalities).

These three groups of factors may be classified by their role in the genesis and dynamics of EDs. Certain genetic and psychological elements have been believed to be factors for vulnerability or predisposition. For example, some polymorphisms of certain genes associated with serotonin, dopamine, leptin, ghrelin, oestrogen receptors and others have been proposed as genetic factors associated with a predisposition or vulnerability to EDs.11 Also, certain personality traits12 and some psychological characteristics, such as problems with anxiety and depression13 and low self-esteem,14 have been proposed as predisposing factors. In addition, there are triggering factors, associated with experiences or environmental conditions that, through epigenetic and/or psychological mechanisms, may promote the onset of EDs, such as traumatic experiences15 (which may include some family factors, especially in families with a history of physical or sexual abuse). Finally, there are maintenance factors that, by their nature, contribute to the persistence and stability of these disorders. These may include some sociocultural and family elements.

In relation to sociocultural factors, some recent studies have taken an interest in the effect of the use of social networks and the risk of EDs. Mabe et al.16 found Facebook use to be associated with maintenance of anxiety and concern about body weight and body shape. They concluded that the use of this social network may contribute to disordered eating and a risk of EDs. Tiggemann et al.,17 in a study in adolescents 13–15 years of age, concluded that the Internet represents a powerful sociocultural medium that affects adolescents’ body image. A recently published study found that Instagram use may be associated with the onset and progression of EDs.18 Levine et al.,19 based on a critical review and a rigorous analysis of the effect of mass communication media, affirmed that “the content, use, and experience of mass media — in and of themselves, and in the context of synergistic messages from peers, parents, and coaches — renders them a possible causal risk factor” for EDs. In addition, athletes and people who exercise regularly have been shown to be vulnerable to EDs20,21 and confirmed to present some individual risk factors. Castro-López et al.,22 in a study of gym-goers, found that the risk of EDs is associated with impulsivity and interpersonal mistrust, ineffectiveness, fear of maturity and self-concept. Behar et al.23 reported that 18% of people who exercise in gyms, mostly females, are at risk of EDs. These people, compared to a group with a clinically confirmed ED, had obtained similar values on variables of desire for thinness, body image dissatisfaction, fear of maturity and perfectionism.

This study was based on the hypothesis that the use of social networks by female gym-goers could increase the risk of problematic eating behaviours. This hypothesis arose from an analysis of the literature related to the possible effect of sociocultural and individual factors on the eating behaviour of some women who regularly go to fitness centres.

MethodsDesignThe study had the objective of reporting and analysing the relationship between the risk of EDs and the use of social networks by female gym-goers in Medellín using a cross-sectional quantitative study, with a non-experimental design on a descriptive level. Intentional or convenience non-probability sampling was performed in 13 gyms in the city. A total of 337 females 15–30 years of age who had been going to the gym regularly for more than four months were enrolled.

InstrumentsEAT-26 (Eating Attitudes Test). The Spanish version from Gandarillas et al. was used.24 A study by Constaín et al.25 on the validity and diagnostic utility of the EAT-26 scale for evaluating the risk of EDs in a female population in Medellín reported excellent reliability and sensitivity values, and a suitable value for specificity, appropriate for screening for possible EDs in an at-risk population. The EAT-2626 consists of 26 items, with Likert-scale responses, that enquire about concerns and symptoms associated with EDs. It comprises three factors: diet (items on behaviours of avoiding fattening foods and concerns about thinness), bulimia and preoccupation with food (items on bulimic behaviours and thoughts about food), and oral control (items on self-control of food intake and pressure from others to gain weight).

Survey on use of social networks: An eight-question survey was designed, with dichotomous categorical “yes or no” responses:

- 1

Are the comments and likes that you get on the photos you publish to social networks important?

- 2

Do you untag yourself on social networks because you think that you do not look good?

- 3

Do you use Photoshop or another photo editor to retouch your photos before you upload them to social networks?

- 4

Do you take photos to show your progress at the gym?

- 5

Do you constantly compare your photos to those of other people who in your opinion have a ‘better figure’ than you?

- 6

When you upload a photo to Instagram, do you hope to get likes and positive comments on how you look?

- 7

Do you use social networks more than six hours per day?

- 8

Do you take more than 13 selfies a day with the intention of uploading them to social networks?

Females in 13 gyms in the city were contacted directly. The study objective was explained to them and they were provided with the informed consent form, which had been approved by the bioethics committee. For those under 18, their assent and the consent of their legal representative were obtained. Of the 337 females who received the information, 301 filled in and submitted all the requested questionnaires. The participants self-administered the two instruments. The data were organised and analysed using the χ2 test in SPSS version 24.

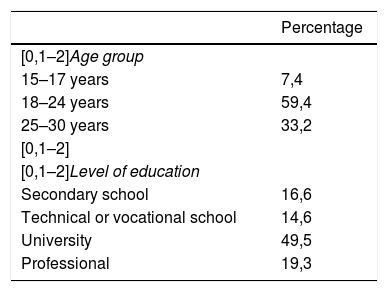

ResultsThe study was conducted with 301 users of 13 gyms in Medellín. The mean age was 22.73 years (σ = 3.8). The minimum age was 15, and the maximum age was 30. Table 1 presents the percentage distribution of the sample by age and level of education. In terms of age, 59.4% of the sample was 18–24, 33.2% was 25–30 and 7.4% was 15–17. In terms of level of education, 49.5% of participants were university students. Females with a secondary-school education (16.6%), technical or vocational school education (14.6%) or professional education (19.3%) were also included.

EAT-26 results were classified according to the conclusions of Constaín et al.25 for evaluating the risk of EDs in a female population in Medellín. This study determined a cut-off point for determining a risk of EDs of ≥11 points. According to those researchers, the probability of correctly classifying a person with that score is 97.3% (z = 20.70; p < 0.0001). Based on this classification criterion, 143 (47.5%) cases with a risk of EDs and 158 (52.5%) cases without a risk were identified. As Table 2 shows, of the 143 cases with a risk, 52% were in the 18–24 age group, 42% were in the 25–30 age group and 36.4% were in the 15–17 age group. Regarding level of education, 55.2% of females with a risk of EDs had a professional education, 47.7% had a university education, 46% had a secondary-school education and 38.6% had a technical or vocational education.

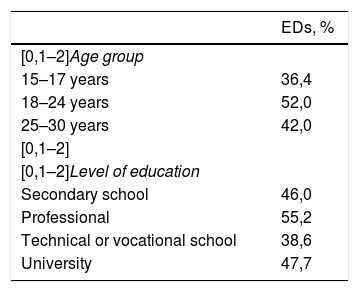

To determine whether there was any statistically significant relationship between age, education and cases with or without a risk of EDs, a χ2 test was performed. No association was found with age (χ2 = 3.772; p = 0.155) or education (χ2 = 2.804; p = 0.423). To find out whether there was any statistically significant difference between the use of social networks and the risk of EDs, a χ2 test was performed. Table 3 presents the results. Differences with asymptotic significance values less than 0.05 (statistically significant) were found with the following questions: “Do you take photos to show your progress at the gym?”, “Do you constantly compare your photos to those of other people who in your opinion have a ‘better figure’ than you?” and “When you upload a photo to Instagram, do you hope to get likes and positive comments on how you look?”.

Test of association between use of social networks and risk of EDs.

| [0,2–3]Risk of EDs | ||

|---|---|---|

| χ2 | p | |

| Are the comments and likes that you get on the photos you publish to social networks important? | <0,001 | 0,984 |

| Do you untag yourself on social networks because you think that you do not look good? | 1,906 | 0,167 |

| Do you use Photoshop or another photo editor to retouch your photos before you upload them to social networks? | 0,105 | 0,746 |

| Do you take photos to show your progress at the gym? | 4,883 | 0,027* |

| Do you constantly compare your photos to those of other people who in your opinion have a 'better figure' than you? | 12,111 | 0,001* |

| When you upload a photo to Instagram, do you hope to get likes and positive comments on how you look? | 3,893 | 0,048* |

| Do you use social networks more than six hours per day? | 0,179 | 0,673 |

| Do you take more than 13 selfies a day with the intention of uploading them to social networks? | 0,720 | 0,396 |

ED: eating disorder.

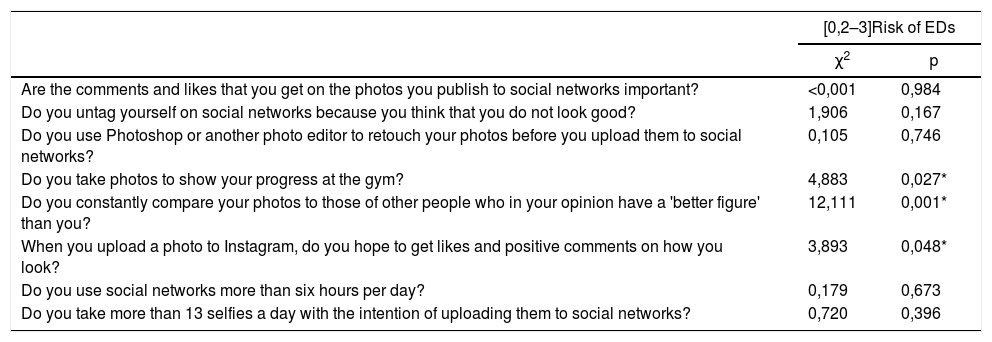

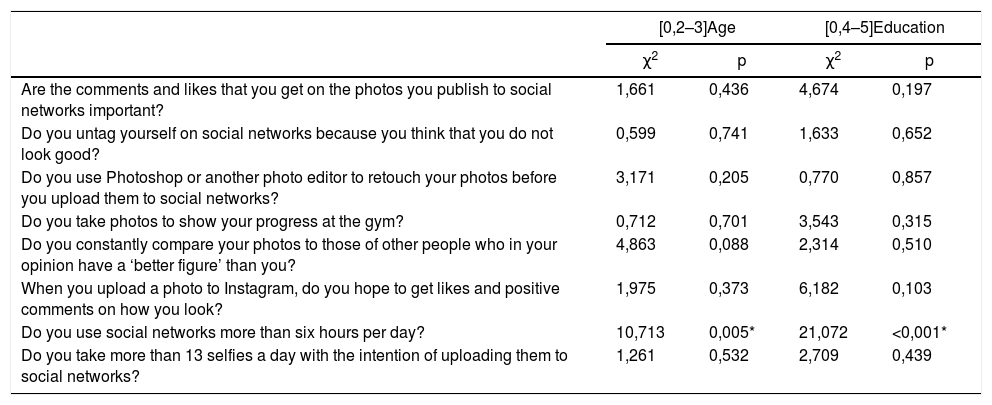

Finally, to determine whether there was any statistically significant difference between age, education and cases with a risk of EDs, a χ2 test was performed. Table 4 presents the results. The only difference with a p-value less than 0.05 (statistically significant) was seen for both age and education with the question “Do you use social networks more than six hours per day?”.

Test of association between the use of social networks and the age and level of education of the group with a risk of EDs.

| [0,2–3]Age | [0,4–5]Education | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | p | χ2 | p | |

| Are the comments and likes that you get on the photos you publish to social networks important? | 1,661 | 0,436 | 4,674 | 0,197 |

| Do you untag yourself on social networks because you think that you do not look good? | 0,599 | 0,741 | 1,633 | 0,652 |

| Do you use Photoshop or another photo editor to retouch your photos before you upload them to social networks? | 3,171 | 0,205 | 0,770 | 0,857 |

| Do you take photos to show your progress at the gym? | 0,712 | 0,701 | 3,543 | 0,315 |

| Do you constantly compare your photos to those of other people who in your opinion have a ‘better figure’ than you? | 4,863 | 0,088 | 2,314 | 0,510 |

| When you upload a photo to Instagram, do you hope to get likes and positive comments on how you look? | 1,975 | 0,373 | 6,182 | 0,103 |

| Do you use social networks more than six hours per day? | 10,713 | 0,005* | 21,072 | <0,001* |

| Do you take more than 13 selfies a day with the intention of uploading them to social networks? | 1,261 | 0,532 | 2,709 | 0,439 |

ED: eating disorder.

This study recorded a rate of 47.5% of cases with a risk of EDs. As mentioned in the “Results” section, this percentage was calculated based on the cut-off point (≥11 points) proposed in a study by Constaín et al.25 for evaluating the risk of EDs in a female population in Medellín. Among the studies conducted in Colombia to determine the prevalence of EDs,5–8 only that by Piñeros et al.5 used the EAT-26 instrument with males and females 10–12 years of age. This study used the conventional cut-off point (≥20 points) to estimate the risk of EDs, and reported a prevalence of 15%, predominantly in women. A study by Ángel et al.6 used the Encuesta de Comportamiento Alimentario [Food Behaviour Survey (ECA)] and reported a rate of 30.7%, mostly in females. The studies by Rueda et al.7,8 used the questionnaire for screening for EDs (SCOFF) and reported a prevalence of 29.9% in adolescents aged 10–19 years in school and 38.7% in university students aged 17–25 years. Hence, it was not possible to compare the results of this study to those of other studies conducted in Colombia, due to mismatches in ages, instruments and scoring criteria. To date, this is the first study on EDs conducted in female gym-goers in Colombia. However, this high prevalence (half of gym-goers had a risk of EDs) backed the findings of other studies that have reported associations between exercise and risk of EDs.20–23 In addition, the highest percentage of cases with a risk of EDs was in the 18–24 age group (52%), and the second highest was in the 25–30 age group (42%); this was consistent with Rueda et al.,7 who maintained that “females 18–29 years of age represent the population sector at highest risk of EDs, even higher than adolescents”. In addition, the results with regard to level of education were also consistent with those of Rueda et al.,7,8 since the risk of EDs was more prevalent among those with a university or professional education than those with a high-school education.

The χ2 tests showed that the groups of cases with and without a risk differed in some ways with regard to use of social networks. The group with a risk took more photos to show their progress at the gym, more often compared their photos to those of other people who in their opinion had a “better figure” and, when they uploaded a photo to Instagram, more often hoped to get likes and positive comments on how they looked. Taking more photos to show one’s progress at the gym may be associated with not only a desire to perceive progress towards improvement of one’s physical image, but also a desire for others to be aware of that improvement. In other words, it may relate not only to self-esteem (increasing body image satisfaction), but also a desire for recognition and social validation.

Although it cannot be affirmed that this behaviour was associated with a negative self-image (body image dissatisfaction) in this sample, that relationship has indeed been reported in similar samples.27 It is more likely that females classified as having a risk of EDs who took photos to show their progress at the gym had a certain amount of dissatisfaction with their own body image. Interest in public displays of improvements to one's figure and physical appearance may indicate sensitivity to cultural stereotypes of beauty. The sociocultural perspective on body image28 emphasises the importance of communication media and indicates that exposure to communication media content may convey unrealistic images of female beauty. Internalisation of those distorted images may lead to a state of body image dissatisfaction, which is predictive of disordered eating.29

Narcissism has been associated with EDs. Lehoux et al.30 found that patients with abnormal eating behaviour had higher levels of narcissism than the psychiatric population and healthy controls. It has been indicated that overinvestment in body image and eating behaviours in females with EDs could be an attempt to stabilise their self-image.31 The relationship between narcissism and self-esteem is contradictory in the population with EDs. Although low self-esteem is a characteristic of EDs, it is not a characteristic of narcissism, in which self-esteem is heightened. In narcissism, self-image is overestimated. In EDs, it is underestimated. Boucher et al.32 analysed this discrepancy according to two types of self-esteem (explicit and implicit) and two types of narcissism (grandiose and vulnerable). In their study, patients with EDs had lower levels of explicit self-esteem and higher levels of the two types of narcissism than patients with anxiety disorders and healthy people.

Marshall et al.33 reported an association between narcissism and using Facebook to show off diet and exercise achievements. According to them, this behaviour may express a desire on the part of this type of person to show others their fascination with themselves. People who often post their progress at the gym are not just interested in standing out from everybody else; they also want others to know that they value beauty and fitness. A preoccupation with one’s appearance and a desire to be the centre of attention are characteristic of narcissists.34 The study by Marshall et al.33 also found narcissism to be predictive of numbers of likes and comments when these people updated their status on Facebook; this finding was consistent with that of this study, as the group with a risk of EDs hoped to get more likes and positive comments on how they looked when they shared photos on social networks.

According to Boucher et al.,32 the results of their study highlighted the contribution of vulnerable narcissism, compared to grandiose narcissism, to the genesis and dynamics of EDs. In particular, a component of this type of narcissism, the contingent self-esteem subscale, which refers to alteration of self-esteem in the absence of external sources of admiration and recognition, presented significantly higher levels than the other two groups. This subscale included items such as: “When others don't notice me, I start to feel worthless” and “It’s hard to feel good about myself unless I know other people admire me.” Uploading photos to show progress at the gym and hoping to get likes and positive comments are behaviours that may be associated with this type of narcissism in the female population with EDs.

It has been found that university students who get negative comments from their peers on Facebook have a higher probability of reporting EDs.35 It is also known that comparing physical appearances may lead to spending more time on Facebook and having disordered eating.36 Mabe et al.37 conducted a study in the United States to determine the correlation between Facebook use and the risk of developing an eating-related psychopathology. They reported that large numbers of adolescents, especially females, had a habit of not only comparing their photos to those of other women and untagging those that they did not like, but also attaching greater importance to the comments and likes that their friends posted to their accounts. The behaviour of untagging photos in particular may be interpreted in two ways: it may be done because the photos have not received enough likes or flattering comments, or it may be a way to avoid being a target of comparisons.

Although the groups with a risk and without a risk did not differ statistically in terms of number of hours spent using social networks (more than six hours per day), in the group with a risk, both by age (χ2 = 10.713; p = 0.005) and by level of education (χ2 = 21.072; p < 0.001), differences on this item were indeed seen. A recent study38 with a large sample of Canadian females 12–29 years of age found an association between number of hours spent using social networks (more than 20 h per week) and level of body image dissatisfaction. These data are also consistent with the reports of a study with Australian females 13–18 years of age which indicated that number of hours spent using Facebook was positively associated with level of body image dissatisfaction.39 These and other studies40 reinforced the notion that Facebook use is more strongly correlated with a poor body image than general Internet use.38

Carter et al.38 believed that the time people spend using Facebook increases their exposure to sociocultural forces and, as said, this exposure to distorted content may present the user with unrealistic images which, when internalised, promote the development of a state of body image dissatisfaction. One psychological mechanism that enhances the effects of these forces is comparison,41 along with low self-esteem. As reported in this study, the group of cases with a risk differed statistically (χ2 = 12.111; p = 0.001) from the group without a risk on the item on comparing one’s photos to those of other people who in their opinion had a “better figure”. The possible combination of body image dissatisfaction and contingent self-esteem, in a context of recurrent use of social networks, may lead to comparisons with idealised standards turning into psychological pressure to achieve a retouched aesthetic that does not really exist outside the digital sphere.

Safrán et al.42 examined whether preoccupation with body image (e.g. appearance and weight appraisal) played a role in the relationship between time spent on social networks and abnormal eating behaviours. In a sample of female undergraduate students, they found that appraisal of one’s physical appearance was effectively mediated by excessive time on social networks and eating-related preoccupations. Tiggemann et al.41 had already noted that the more time spent on Facebook looking at photos, the greater the internalisation of and the desire for being thin. Turner et al.43 recently reinforced this idea, since the results of their study showed that the more time one spends using Instagram to follow profiles that promote healthy eating (such as those of fitness celebrities), the greater the trend towards orthorexia nervosa, an ED with a high rate of comorbidity with anorexia nervosa.

Holland et al.44 conducted a study with females who posted “fitspiration” images to Instagram with the apparent objective of encouraging people to lead a healthy lifestyle with diet and exercise. The purpose of the study was to characterise the eating and exercise habits of women posting images of muscle hypertrophy to Instagram. The researchers found that the text accompanying the images induced weight-related guilt and promoted extreme attitudes around exercise. Based on the inventories applied, it was found that nearly one-fifth of females (17.5%) who posted images of muscle hypertrophy to Instagram were at risk of EDs. They also had high scores on measures of disordered eating and compulsive exercise, indicating that females who post images with this type of encouragement are working out to achieve an ideal body as socially prescribed (thin and toned), without regard for what it means to be healthy.

Consistent with the above-mentioned results, some studies have shown that use of social networks such as Facebook has been significantly associated with internalisation of an ideal of thinness, body image dissatisfaction and EDs. It has also been proposed that uploading photos to social networks may be linked to concerns about one’s own body image, with platforms like Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat being particularly influential with respect to body self-perception. In this context, females who are more vulnerable to negative evaluation could have a tendency to compare themselves to others. That could be the basis for strong self-disapproval or even a distorted body image, which could be contributing to the genesis or dynamics of EDs.

The greater the use of social networks as a medium for self-image approval, the more abnormal eating attitudes and the lower the body image satisfaction. This establishes a high degree of vulnerability at which an ED develops or is maintained, particularly in a population that utilises gyms and fitness centres. This population has, in theory, a desire to improve their physical appearance, which, combined with the use of social networks, may devolve into a trend towards EDs. A very close relationship has been identified between Facebook use, especially use related to photographic content, and a lack of acceptance of one’s own body weight, plus internalisation of thinness as an ideal and a tendency to compare how one looks to how other people look.45

Undoubtedly, one of the main limitations of this study was that it did not enrol a control group with females who were social network users but not gym-goers. As data on the use of social networks by female non-gym-goers was not available, it was not possible to determine whether there were statistically significant differences in this behaviour between gym-goers and non-gym-goers. That information would have been useful for determining whether the risk of EDs is associated with the use of social networks regardless of whether females go to the gym regularly, or instead being users of these fitness centres effectively affects risk genesis and/or maintenance.

With the results of this study, it can only be concluded that: a) nearly half the female gym-goers were at risk of EDs and b) there were differences between the groups with and without a risk along some dimensions of the use of social networks. However, it was not possible to determine whether the fact of being female gym-goers was associated with a particular profile in the use of social networks compared to female non-gym goers. With these results, it can only be affirmed that there were indeed certain group-dependent differences in female users of fitness centres. Subsequent studies could analyse whether the use of social networks is associated with the risk of EDs in females who do not go to gyms.

Further studies could also enrol a male population to analyse these variables by sex. Males were not included in this study as the review of past studies, particularly the global burden of disease study and the Colombian studies on the subject, highlighted the fact that the prevalence and impact of EDs is higher in female adolescents and young adults. Regarding the statistical analyses, multivariate techniques involving pathway analyses and structural equations would most certainly have been more powerful in examining questions on this topic. However, the difficulty of having a standardised instrument available for measuring the social network use variable precluded working with discrete quantitative variables, rendering it necessary to resort to analyses suited to working with categorical variables.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The second author would like to thank the students in the Psychology programme at Universidad Católica Luis Amigó [Luis Amigó Catholic University] who, as part of their undergraduate work, formed a team that took part in data collection and organisation.

Please cite this article as: Restrepo JE, Castañeda Quirama T. Riesgo de trastorno de la conducta alimentaria y uso de redes sociales en usuarias de gimnasios de la ciudad de Medellín, Colombia. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:162–169.