The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the magnitude of mental illnesses such as depression, not only in the general population, but also in healthcare personnel. However, in Peru the prevalence, and the associated factors for developing depression in healthcare personnel, are not known. The objective was to determine the prevalence and identify the factors associated with depression in healthcare personnel, in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

MethodsAn analytical cross-sectional study was carried out from May to September in healthcare establishments. A sample of 136 health workers were included and a survey was applied to collect the data. Depression as a dependent variable was measured using the Zung self-report scale. To identify the associated factors, the bivariate and multivariate analysis was performed by logistic regression with STATA v 14.

ResultsThe prevalence of depression was 8.8% (95%CI, 4.64–14.90). Having a family member or friend who had died from COVID-19 was associated with depression (OR = 6.78; 95%CI, 1.39–32.90; p = 0.017). Whereas the use of personal protective equipment was found to be a protective factor against developing depression (OR = 0.03; 95%CI, 0.004−0.32; p = 0.003).

ConclusionsApproximately 1 in 10 healthcare professionals and technicians developed depression during the COVID-19 pandemic in this study. In addition, having relatives or friends who had died from COVID-19 was negatively associated with depression and use of personal protective equipment was identified as a protective factor.

La pandemia de COVID-19 ha incrementado la magnitud de enfermedades mentales como la depresión no solo entre la población general, sino también en el personal de salud. En Perú no se conocen la prevalencia y los factores asociados con depresión en personal de salud. El objetivo es determinar la prevalencia e identificar los factores asociados con depresión en el personal de salud, en el contexto de la pandemia por SARS-CoV-2.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio transversal analítico entre mayo y septiembre en establecimientos de salud. Se incluyó una muestra de 136 trabajadores de la salud y se aplicó una encuesta para recoger los datos. La variable dependiente depresión se midió con la escala autoaplicada de Zung. Para identificar los factores asociados, se realizaron análisis bivariado y multivariado por regresión logística con STATA v 14.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de depresión es del 8,8% (IC95%, 4,64–14,90). Se asociaron con depresión el antecedente de tener familiar o amigo muerto por COVID-19 (OR = 6,78; IC95%, 1,39–32,90; p = 0,017). En cambio, se encontró que el uso de equipos de protección personal (EPP) es un factor protector contra la depresión (OR = 0,03; IC95%, 0,004–0,32; p = 0,003).

ConclusionesAproximadamente 1 de cada 10 profesionales y técnicos de salud sufrió depresión durante la pandemia de COVID-19 en este estudio. Además, el antecedente de tener familiares o amigos muertos por COVID-19 se asoció negativamente con depresión y el uso de EPP se identificó como factor protector contra la depresión.

In November 2019, there was an outbreak of atypical pneumonia of unknown aetiology in the city of Wuhan, China.1 A few weeks later, the aetiological agent was identified as a new betacoronavirus, SARS-CoV-2,1 which belongs to the same family as SARS and MERS.2 These viruses cause zoonotic diseases (transmitted from animals to humans).3

The clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV2 infection vary widely from mild infection (81% of symptomatic cases) to severe infection, characterised by pneumonia, accompanied by dyspnoea, tachypnoea and decreased oxygen saturation.4 In the critical form, there may be respiratory failure, septic shock and/or multiple organ failure.4 Symptoms appear up to 2 weeks after exposure to a sick person. However, the mean incubation period varies from 3 to 7 (median, 5.1) days.4

As of 18 October 2021, 240,805,141 confirmed cases had been reported worldwide and 4,901,012 of these patients died. The United States had the highest number of cases (44,937,514), while Peru had reported 2,189,165 confirmed cases and 199,816 deaths (fatality, 9.1%)5 since the detection of the first confirmed imported case on 5 March 2020,6 which was due to inadequate strategies implemented at the beginning of the pandemic, the shortage of human resources and insufficient knowledge of this disease. In the department of Piura, by 16 October 2021, 87,997 cases and 11,962 deaths (fatality, 13.5%) had been reported.7

Peru's health services are organised into first tier low-complexity facilities (I1–I4), which are responsible for specific promotion and protection activities, second tier intermediate-complexity facilities (II1–II2) and third tier high-complexity, specialised facilities (III1–III2).8 In order to deal with the pandemic, many of the first tier health services only attended to urgent and emergency cases at the start of the pandemic, and outpatient consultations were drastically reduced. Subsequently, the identification, diagnosis and follow-up of cases, as well as the mobilisation of resources for the treatment and control of COVID-19 cases and of contacts with mild acute respiratory infection, were reinforced.9 However, in Chile, primary healthcare facilities quickly took on the role of diagnosing COVID-19, implementing isolation measures for infected cases and testing contacts.10

In comparison to the general population, healthcare personnel are at a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection due to greater exposure than the general population.11 The risk to this group and their family members of becoming infected results in increased stress, which means that this population is at greater risk of some form of mental disorder, such as depression and anxiety, which are the most prevalent.12

In 2015, depression was the third most common cause of disability worldwide.13 Its pathophysiology is still poorly understood. One thing we do know is that there is an imbalance in the levels of monoamine neurotransmitters (serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine or all three).14 In order to diagnose depression, 5 or more symptoms must be present over a period of 2 weeks.15 Some of the main symptoms are a depressed mood, anhedonia (loss of interest or pleasure in things you once enjoyed), as well as changes in appetite or weight and difficulty sleeping (insomnia or hypersomnia).16 Likewise, in Peru, the prevalence of depression in resident doctors in pre-pandemic studies varied between 13.3 and 14.6%.17,18

In Peru, the prevalence of depression in healthcare personnel within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic is unknown, and associated factors have not been identified, despite being a country with one of the highest mortality rates in the world.5 In other countries, studies have been conducted on the prevalence of depression and associated factors among healthcare personnel exposed to suspected or confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2. In a systematic review conducted during the SARS-CoV2 pandemic, the global prevalence was 22.8%. Furthermore, in 2 individual studies using the Zung scale, the prevalence varied between 32.81 and 50.4%.15,16 At the Dos Campos Gerai regional university hospital, the prevalence of depression was 25%, and being female, aged 21–30 years and single were associated with depression.19

Knowing the magnitude of the problem and identifying the factors associated with depression in healthcare personnel is very useful for the multidisciplinary approach to depression,20 especially in a context of significant gaps in human resources in the first line21 and the limited availability of PPE.22

The objective of this study, therefore, was to determine the prevalence and to identify factors associated with depression in healthcare personnel, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

MethodsDesign and description of the studyThis was an observational study with a cross-sectional design to determine the prevalence and potential factors associated with depression in healthcare personnel from 5 healthcare facilities in the Luciano Castillo Colona Subregion of the Department of Piura, Peru, within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

For this study, the Zung Scale was used, validated in Peru by Novara et al. in 1985 with 178 patients who attended the outpatient clinic of the Honorio Delgado-Hideyo Noguchi Mental Health Institute with α = 0.75, indicating a good reliability of the instrument.23 If the participant achieves a score ≥50, the response variable is depression.24

Study populationThe population included healthcare personnel (professionals and technicians) who cared for patients with COVID-19 and other diseases at 5 healthcare facilities during the pandemic, selected for their ease of access. The facilities selected were the ones with the highest patient-treatment capacity along the coast of the Luciano Castillo Colona Health Subregion, in the Department of Piura, with an assigned population estimated at 951,311 inhabitants.

Sample size and selectionThe sample size was determined using the corresponding instrument of the Epi Info 7.1.5.2 software tool developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States.

For this purpose, the following parameters were taken into account: 95% level of confidence, expected prevalence of depression of 45.6%25 at the time of study approval, and a precision of 7%. The minimum sample size calculated was 125 but the addition of 30% was considered so as to reduce the problem of non-response rate, resulting in a final sample size of 163 participants. Participants were selected using stratified random sampling with allocation proportional to size per type of personnel and per healthcare facility based on the sampling framework provided by the personnel area of each healthcare facility in coordination with the Epidemiology Office of the Luciano Castillo Colona Health Subregion.

Evaluation of depression symptomsDepression symptoms were evaluated using the 20-item Zung Scale. Some items were worded as symptomatically positive, rated on a scale from 4 to 1 (a little of the time, some of the time, part of the time and most of the time), and others were symptomatically negative, rated on a scale from 1 to 4. The scale uses a standardised scoring algorithm with a cut-off point ≥50 points to define depression symptoms and a total score range of 20 to 80.23

CovariatesThe following demographic variables were included: age (expressed in years), sex (male and female), marital status (married, single, separated, divorced and widowed), profession or occupation (doctor, nurse, medical technologist, obstetrician, biologist and technician), category of healthcare facility according to the Peruvian standard (I-4, II-1 and II-2), type of employment (appointed, administrative service contract, third party service, fixed-term contract and other), department or service employed in (hospital ward, emergency department, triage, intensive care unit [ICU], laboratory and other) and chronic illnesses (yes or no). Independent variables included: family members or friends infected with SARS-CoV-2 (yes or no), family members or friends who have died from COVID-19 (yes or no), types of patients they attended to (with suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection or other reasons) and if personal protective equipment (PPE) was received (yes or no). For a better analysis, it was decided to recategorise those variables with minimum or zero values: marital status (married, single and other: separated, divorced and widowed), profession (nurse, doctor, technician and other: medical technologist, biologist and obstetrician), type of contract (appointed, administrative service contract and other: fixed-term contract, third-party services and other) and department where employed (emergency department, other: outpatient clinic, obstetrics, etc.), hospital ward, intensive care unit (ICU), laboratory and triage.

Statistical analysisStudy data were collected using an online survey on Google Forms. In order to correctly record the data, epidemiology managers from each facility were trained via Zoom. They each received the list of selected personnel in order to locate them and ask them to complete the survey. After completing the survey, the data were exported to an MS-Excel database for sorting and coding. In addition, two investigators performed an independent quality control and any duplicated data were deleted by consensus (Fig. 1). For this purpose, they took into consideration the presence of two identical records entered on the same date and with a very short time difference in minutes or seconds between the first and the second entry.

STATA 16 was used for the statistical analysis. To describe categorical variables, absolute and relative frequencies were used. Normality was assessed for numerical variables and medians [interquartile range] were reported if variables had a non-normal distribution. For the bivariate analysis of categorical variables, the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used based on the statistical assumptions. Differences were considered significant if p < 0.05. In the case of age, normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test and homogeneity of variance was assessed using Levene's test. As age is a variable with a normal distribution, the Student's t-test was used for independent samples to compare means. To identify factors associated with the prevalence of depression, crude odds ratios (OR) were calculated using multivariate logistic regression, after verifying that the prevalence of depression was <10%. Depression was considered the dependent variable, while sociodemographic and SARS-CoV-2-related variables were considered independent variables. For the final identification of associated factors, adjusted ORs (aOR) were calculated. Results with p ≤ 0.05 were included to calculate ORs using logistic regression. ORs are presented considering a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and p < 0.05. ORs were also adjusted for confounding variables (age, sex and family members or friends who had died from COVID-19), in accordance with earlier studies.16,25

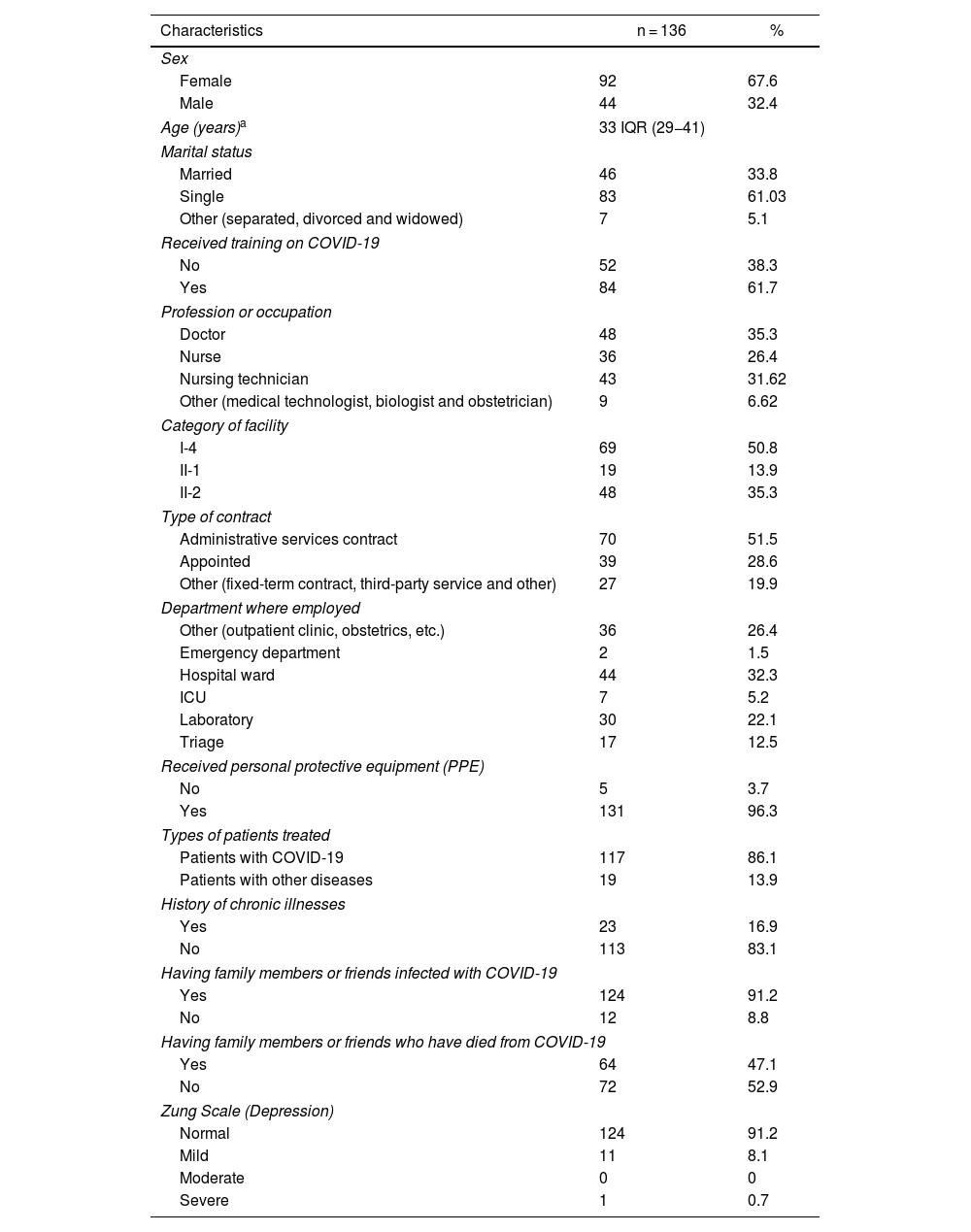

ResultsDescriptive analysis of variablesParticipants' characteristicsUsing an online survey, this cross-sectional study surveyed 136 participants (Fig. 1), whose characteristics are presented in Table 1. It is observed that the median age is 33 [29−41] years; 67.7% (92) were female and the majority were single (61%; 83). Regarding the other characteristics, 35.3% (48) were doctors; 50.8% (69) belonged to category I-4 healthcare facilities, 51.5% (70) were contracted under the Administrative Service Contract modality, 32.3%, (44) worked on hospital wards, and 83.1% responded that they did not suffer from any chronic illness. Regarding SARS-CoV2-related variables, 61.7% (84) received training, 91.2% (124) had a family member or friend infected with SARS-CoV2, 47.1% (64) had a family member or friend who had died from COVID-19, 86.1% (117) looked after patients infected with SARS-CoV2 and 96.3% (131) received personal protective equipment.

Characteristics of healthcare personnel, Department of Piura, Peru, 2020.

| Characteristics | n = 136 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 92 | 67.6 |

| Male | 44 | 32.4 |

| Age (years)a | 33 IQR (29−41) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 46 | 33.8 |

| Single | 83 | 61.03 |

| Other (separated, divorced and widowed) | 7 | 5.1 |

| Received training on COVID-19 | ||

| No | 52 | 38.3 |

| Yes | 84 | 61.7 |

| Profession or occupation | ||

| Doctor | 48 | 35.3 |

| Nurse | 36 | 26.4 |

| Nursing technician | 43 | 31.62 |

| Other (medical technologist, biologist and obstetrician) | 9 | 6.62 |

| Category of facility | ||

| I-4 | 69 | 50.8 |

| II-1 | 19 | 13.9 |

| II-2 | 48 | 35.3 |

| Type of contract | ||

| Administrative services contract | 70 | 51.5 |

| Appointed | 39 | 28.6 |

| Other (fixed-term contract, third-party service and other) | 27 | 19.9 |

| Department where employed | ||

| Other (outpatient clinic, obstetrics, etc.) | 36 | 26.4 |

| Emergency department | 2 | 1.5 |

| Hospital ward | 44 | 32.3 |

| ICU | 7 | 5.2 |

| Laboratory | 30 | 22.1 |

| Triage | 17 | 12.5 |

| Received personal protective equipment (PPE) | ||

| No | 5 | 3.7 |

| Yes | 131 | 96.3 |

| Types of patients treated | ||

| Patients with COVID-19 | 117 | 86.1 |

| Patients with other diseases | 19 | 13.9 |

| History of chronic illnesses | ||

| Yes | 23 | 16.9 |

| No | 113 | 83.1 |

| Having family members or friends infected with COVID-19 | ||

| Yes | 124 | 91.2 |

| No | 12 | 8.8 |

| Having family members or friends who have died from COVID-19 | ||

| Yes | 64 | 47.1 |

| No | 72 | 52.9 |

| Zung Scale (Depression) | ||

| Normal | 124 | 91.2 |

| Mild | 11 | 8.1 |

| Moderate | 0 | 0 |

| Severe | 1 | 0.7 |

The overall prevalence of depression was 8.8% (95% CI, 4.64–14.90); among those who only attended to patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, prevalence was 9.4% (11/117); and among those who attended to other types of patients, prevalence was 5.3% (1/19), with no statistical significance. The prevalence of depression by profession was: nurses, 1.4%; doctors, 3.6%; technicians, 3% and other professions, 0.7%. The mean Zung Scale score was 36.6 points (Table 1), with non-normal distribution and homogeneity of variances. According to the cut-off scores of the Zung Scale <50 points is a normal patient (without depression), 50–59 is mild depression, 60–69 is moderate depression and >70 is severe depression. It was observed that 91.2% (n = 124) did not have depression and 8.8% (n = 12) did have depression. Of these, 11 had mild depression and only 1 had severe depression.

Bivariate analysisThe category of healthcare facility, having received PPE and having a family member or friend who had died from COVID-19 are significantly related to depression (Table 2). For the bivariate analysis, it was decided to categorise the profession variable, divided into doctors and other professions. Even so, the variable was not statistically significant.

Bivariate analysis in healthcare personnel, Department of Piura, Peru, 2020.

| Depression | No depression | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Sexb | 0.171 | ||||

| Female | 6 | 4.4 | 86 | 63.2 | |

| Male | 6 | 4.4 | 38 | 28.0 | |

| Age | |||||

| Years | 33.25 | 35.7 | 0.366 | ||

| Marital statusa | 0.235 | ||||

| Married | 2 | 1.5 | 44 | 32.5 | |

| Single | 10 | 7.3 | 73 | 53.6 | |

| Other (separated, divorced and widowed) | 0 | – | 7 | 5.1 | |

| Have received training on COVID-19b | 0.798 | ||||

| No | 5 | 3.6 | 47 | 34.7 | |

| Yes | 7 | 5.1 | 77 | 56.6 | |

| Profession or occupationa | 0.753 | ||||

| Doctor | 5 | 3.6 | 43 | 31.8 | |

| Other (nurse, medical technologist, nursing technician) | 7 | 5.1 | 81 | 59.5 | |

| Category of healthcare facilitya | 0.036 | ||||

| I-4 | 7 | 5.1 | 62 | 45.5 | |

| II-1 | 4 | 2.9 | 15 | 11.0 | |

| II-2 | 1 | 0.7 | 47 | 34.7 | |

| Type of contracta | 0.365 | ||||

| Appointed | 5 | 3.6 | 34 | 25.0 | |

| Administrative services contract | 4 | 2.9 | 66 | 48.5 | |

| Other (fixed-term contract, third-party service and other) | 3 | 2.2 | 24 | 17.6 | |

| Department where employeda | 0.110 | ||||

| Other (outpatient clinic, obstetrics, etc.) | 2 | 1.5 | 15 | 11.0 | |

| Emergency department | 4 | 2.9 | 32 | 23.5 | |

| Hospital ward | 0 | – | 44 | 32.5 | |

| ICU | 1 | 0.7 | 6 | 4.4 | |

| Laboratory | 0 | – | 2 | 1.5 | |

| Triage | 5 | 3.6 | 25 | 18.4 | |

| Received personal protective equipment (PPE)a | 0.005 | ||||

| No | 3 | 2.2 | 2 | 1.5 | |

| Yes | 9 | 6.6 | 122 | 89.7 | |

| Types of patients attendedb | 0.476 | ||||

| Patients with COVID-19 | 11 | 8.0 | 106 | 77.9 | |

| Patients with other diseases | 1 | 0.7 | 18 | 13.2 | |

| History of chronic illnessesb | 0.329 | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 2.2 | 20 | 14.7 | |

| No | 9 | 6.6 | 104 | 76.4 | |

| Having family members or friends infected with COVID-19b | 0.286 | ||||

| Yes | 10 | 7.4 | 114 | 83.8 | |

| No | 2 | 1.5 | 10 | 7.4 | |

| Having family members or friends who have died from COVID-19b | 0.009 | ||||

| Yes | 10 | 7.4 | 54 | 39.7 | |

| No | 2 | 1.5 | 70 | 51.4 | |

In the logistic regression analysis, the demographic variables of age, sex, marital status, profession, department where employed, type of contract, category of facility where employed and chronic illnesses were shown to be statistically insignificant. An adjustment was made for marital status, category of the facility and department where employed for confounding variables such as age, sex and family members or friends who had died from COVID-19, and none were shown to be statistically significant.

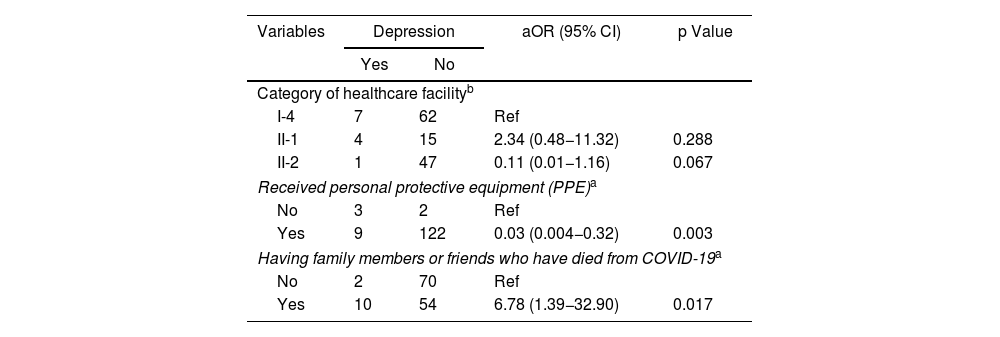

SARS-CoV-2-related factors associated with depressionRegarding SARS-CoV-2-related variables, it was found that having received training on COVID-19, a history of family members or friends infected with SARS-CoV-2 and the type of patient they attend were not statistically significant. However, a history of having family members or friends who had died from COVID-19 (p = 0.019) had a negative association with the development of depression, and having received PPE (p = 0.002) was a protective factor (Table 3). An adjustment was then made for age, sex and family members infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Table 4) and the variables remained significant (p < 0.05).

Logistic regression analysis in healthcare personnel, Department of Piura, Peru, 2020.

| Variables | Depression | aOR (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Category of healthcare facility | ||||

| I-4 | 7 | 62 | Ref | |

| II-1 | 4 | 15 | 2.36 (0.61−9.12) | 0.213 |

| II-2 | 1 | 47 | 0.18 (0.02−1.58) | 0.124 |

| Received personal protective equipment (PPE) | ||||

| No | 3 | 2 | Ref | |

| Yes | 9 | 122 | 0.04 (0−0.33) | 0.002 |

| Having family members or friends who have died from COVID-19 | ||||

| Yes | 10 | 54 | 6.48 (1.36−30.81) | 0.019 |

| No | 2 | 70 | Ref | |

Significant variables adjusted for confounding variables in healthcare personnel, Department of Piura, Peru, 2020.

| Variables | Depression | aOR (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Category of healthcare facilityb | ||||

| I-4 | 7 | 62 | Ref | |

| II-1 | 4 | 15 | 2.34 (0.48−11.32) | 0.288 |

| II-2 | 1 | 47 | 0.11 (0.01−1.16) | 0.067 |

| Received personal protective equipment (PPE)a | ||||

| No | 3 | 2 | Ref | |

| Yes | 9 | 122 | 0.03 (0.004−0.32) | 0.003 |

| Having family members or friends who have died from COVID-19a | ||||

| No | 2 | 70 | Ref | |

| Yes | 10 | 54 | 6.78 (1.39−32.90) | 0.017 |

In this study, in the context of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, the global prevalence of depression in healthcare personnel looking after people with SARS-CoV2 and other patients was 8.8% in a sample of 136 participants. These values are low compared to those of other studies on healthcare personnel also in the context of the pandemic in China, which show prevalences between 13.4 and 45.6%.25,26 The difference with our study could be due to the fact that, in our case, the study was conducted at healthcare facilities with a lower level of complexity: 2 first tier facilities I-4 (Bellavista and Talara Health Centres), 2 tier II-1 facilities (Talara EsSalud and Sullana EsSalud Hospitals), 1 tier II-2 facility (Sullana Hospital) and 1 tier I-4 facility (Tambo Grande Health Centre), and healthcare personnel who attended to patients with other conditions were also included. Likewise, in another study performed in Chile, a prevalence of depressive symptoms of 66% was found among primary healthcare workers,27 a high prevalence that could be due to the moment when the study was performed, April 2020 (beginning of the pandemic),27 when there was a lot of fear, and also to the way the data were collected, unlike our study, which was conducted between May and September 2020. In contrast, studies in China were only performed at more complex hospitals. Furthermore, when applying the surveys, EsSalud moved some healthcare personnel around, as part of its policy, due to the shortage of human resources at its facilities, which could have resulted in an underestimation of the prevalence because some of the personnel selected may have only been working there for a few days. Likewise, by comparing healthcare personnel who attended to patients with SARS-CoV-2 and those who did not, this study found that those who attended to patients with SARS-CoV2 had a higher probability of depression (9.4%) than those who did not look after SARS-CoV2 patients (5.3%). However, this was not statistically significant. This can be contrasted with a study performed in China that compared healthcare personnel looking after patients with SARS-CoV2 and those who did not, which found a higher prevalence than in our study, 40.4% versus 32.2%.16

Furthermore, on comparing the prevalence of depression before the pandemic with the prevalence at the moment of the pandemic when our study was performed, differences are observed. In 2015, a prevalence of 13.3% was found at the Alcides Carrión National Hospital in Callao,17 with a prevalence of 14.6% among resident doctors,18 compared to 8.8% in our study. The high prevalence of depression in the first study17 could be due to the dangerous nature of the area where the hospital is located.17

Likewise, the multivariate regression analysis found that a history of having a family member or friend die from COVID-19 was associated with the development of depressive symptoms (OR = 6.78). This may be because it is assumed that healthcare personnel, especially nurses, are involved in the terminal phases and even the death of patients.28

This result differs from other studies where it was statistically insignificant.29 In our research, although the CI is wide due to the small sample size, this finding is very important when it comes to treating depression in healthcare personnel in the context of Peru and countries that have shown a high mortality rate among healthcare workers. A study involving doctors, nurses and other healthcare personnel during the H1N1 pandemic in 2009 in Mexico, which used a survey and a semi-structured interview, reported anger, fear and anxiety as psychosocial symptoms, because people felt abandoned by the authorities and did not have the essential supplies to treat patients with H1N1. Furthermore, it was reported that 20% of doctors experienced emotional exhaustion, defined as a loss of motivation that usually progresses to feelings of inadequacy and failure,30 which generates a state of great stress and feelings of sadness, considered risk factors for depression. This can be contrasted with the actual situation in Peru, which has the third highest count of doctors who died from COVID-19, with a total number of deaths of 544 as of 18 October 2021.31 Mental illnesses, such as depression, could reduce the ability to respond to the pandemic, especially in the hypothesis of a third wave in Peru. Depression, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), is the leading cause of disability in the world32 and could reduce the quality of care given by healthcare personnel (doctors, nurses and others) due to the symptoms of this disease.

Another important finding of this study is that having received PPE was a protective factor against the onset of depressive symptoms (OR = 0.04). These results are closely linked to what we already know about using preventive measures to reduce the risk of becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2, which would make healthcare personnel calmer and more confident when working with PPE. Despite adjusting this variable for the confounding variables (age and sex, since being aged between 20 and 30 years and being female are considered risk factors for depression13,14), it remained a protective factor (OR = 0.03). This finding confirms the results of a study conducted during the pandemic on factors associated with depression in nurses at Guillan University Hospital, where inadequate access to PPE (OR = 2.62; 95% CI, 1.76–3.91; p < 0.001) was a risk factor for depression.29 In Peru, 252,883,823 items of PPE were purchased and 157,909,39733 were distributed. Deficient delivery of these materials may result in a greater risk of infection among healthcare personnel. However, there is still a need for more studies to find a stronger relationship between these factors. Furthermore, it has been shown that Peru had weaknesses in its response to the pandemic due to the fact that, in recent years, it has experienced a political crisis and has a fragmented health system, among other limitations.22

The other variables, such as sex, age, marital status, training for SARS-CoV-2, profession or occupation, category of healthcare facility, type of contract, department where employed, types of patients attended, chronic illnesses, and family members or friends infected with SARS-CoV-2, were not significantly associated with depression. Probably no relationship was found due to the relatively small size of the study sample and the rotations of EsSalud healthcare personnel at the facilities studied. This study not only evaluated doctors, but also other professions. Working at low-complexity facilities would imply less risk of depression. In contrast to the literature, a study conducted in nurses in Brazil found that being single and having a temporary contract were associated with depression.19 Also, a study performed in Wuhan, China, found that healthcare professionals working at third-tier (higher complexity) hospitals had lower scores than those working at second-tier (lower complexity) hospitals.16 A systematic review found differences in prevalence according to occupation: nurses, 30.30% (95% CI, 18.24–43.84) and doctors, 25.37% (95% CI, 16.63–35.20); women had a prevalence of 26.87% (95% CI, 15.39–40.09); mild cases accounted for 24.60% (95% CI, 16.65–33.51) and moderate/severe cases accounted for 16.18% (95% CI, 12.80–19.87).15 However, another study found that being female (OR = 4.62; 95% CI, 1.24–17.16), having signs of SARS-CoV2 infection (OR = 3.44; 95% CI, 2.11–5.59), chronic illnesses (OR = 2.12; 95% CI, 1.20–3.74) and not having PPE were associated with depression (OR = 1.86; 95% CI, 1.19–2.91).29 Finally, a direct linear relationship has been found between depression and age: the older you are, the greater the risk of depression. The female sex showed a correlation (R2 = 2.5; p < 0.004) and an increase in age (R2 = 0.85; p < 0.001) was associated with depression. In those under the age of 30 years, the prevalence was 36.6%, while in those aged between 30 and 40 years, it was 39.2%.29,34

This study has certain limitations. Firstly, as it is a cross-sectional study, a causal relationship cannot be found; factors associated with depression can only be inferred. Second, the sample size is relatively small due to the context in which the study was conducted (many professionals and technicians were working remotely) and due to healthcare personnel rotations at EsSalud hospitals. Likewise, at some facilities surveys were not applied with the same proportion of participants (type of contract, department where employed, profession), which could have resulted in possible underestimation of the prevalence in these groups. Thirdly, it was not possible to distinguish between current depressive symptoms and those existing before the study. Fourth, an online self-administered questionnaire was used for the study, which could have caused some overestimations of the variables studied. Finally, due to the context in which the study was performed and the difficulties presented, it was decided to use a precision of 7%, which overestimates the sample size of the study.

With regards to the study's strengths, this is a primary study, and its specific data collection method gives it added value, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, unlike other studies, this study based its analysis not only on doctors but also on other occupational groups. Likewise, the validated Zung Scale23 was used. Finally, the use of Google Forms is an innovative method that allowed our study to be performed in times of pandemic.

The protection of healthcare personnel is an imperative component of public health. For this reason, it is essential to care for their mental health by implementing mental health activities (counselling and psychological support) for workers and offering an adequate supply of PPE. A case-control or longitudinal study in healthcare personnel on mental illnesses, including depression, is also recommended to complement the results of this study.

Our study shows that 1/9 healthcare workers had depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, a history of having family members or friends who had died from COVID-19 was also found to be associated with the prevalence of depression. Furthermore, the PPE variable was a protective factor.

FundingSelf-financed by Espinoza-Ascurra G and Gonzales-Graus I.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this study.

We would like to thank Pilar Campos, Fabiola Nieves, Mirna Giron, Dolores Raymundo, José Sandoval and Mariana Vitella for their support. They were all responsible for epidemiology at their healthcare facilities within the Luciano Castillo Colonna Health Subregion, Piura.

Submitted as the thesis for the degree of Doctor of Medicine: "Prevalence and factors associated with depression in healthcare personnel during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in the Department of Piura, Peru", Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas [Peruvian University of Applied Sciences], Lima, Peru.