To identify the main factors determining the health related quality of life (HRQL) in patients with cancer-related neuropathic pain in a tertiary care hospital.

MethodsA cross-sectional analytical study was performed on a sample of 237 patients meeting criteria for cancer-related neuropathic pain. Clinical and demographic variables were recorded including, cancer type, stage, time since diagnosis, pain intensity, physical functionality with the palliative performance scale (PPS), and anxiety and depression with the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS). Their respective correlation coefficients (r) with HRQL assessed with the SF-36v2 Questionnaire were then calculated. Linear regression equations were then constructed with the variables that showed an r≥0.5 with the HRQL.

ResultsThe HRQL scores of the sample were 39.3±9.1 (Physical Component) and 45.5±13.8 (Mental Component). Anxiety and depression strongly correlated with the mental component (r=−0.641 and r=−0.741, respectively) while PPS score correlated with the physical component (r=0.617). The linear regression model that better explained the variance of the mental component was designed combining the Anxiety and Depression variables (r=77.3%; p<0.001).

ConclusionsThe strong influence of psychiatric comorbidity on the HRQL of patients with cancer-related neuropathic pain makes an integral management plan essential for these patients to include interventions for its timely diagnosis and treatment.

Identificar los principales determinantes de la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS) de pacientes con dolor neuropático oncológico en un hospital de tercer nivel de atención.

MétodosEstudio transversal analítico. En una muestra de 237 pacientes con criterios de dolor neuropático de origen oncológico, se midieron variables clínico-demográficas: tipo de cáncer, estadio, tiempo de diagnóstico, intensidad del dolor, funcionalidad física con la escala PPS, y ansiedad y depresión con la escala HADS. Se calcularon sus respectivos coeficientes de correlación (r) con la CVRS medida con el cuestionario SF-36v2™. Con las variables que mostraron r ≥ 0,5 con la CVRS, se construyeron ecuaciones de regresión lineal.

ResultadosLa población mostró puntuaciones de CVRS de 39,3±9,1 (componente físico) y 45,5±13,8 (componente mental). Ansiedad y depresión tuvieron correlación fuerte con el componente mental (r =–0,641 y r =–0,741 respectivamente), mientras que la PPS la tuvo con el componente físico (r=0,617). El modelo de regresión lineal que mejor explicó la varianza del componente mental fue diseñado con las variables ansiedad y depresión combinadas (R=77,3%; p<0,001).

ConclusionesLa fuerte influencia de la comorbilidad psiquiátrica en la CVRS de los pacientes con dolor neuropático oncológico hace necesario que el plan de atención integral de estos pacientes incluya intervenciones para su oportuno diagnóstico y tratamiento.

After heart disease, cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide,1 and the number of cancer deaths is expected to continue rising. The global cancer burden will continue to grow as a result of accelerated population growth, ageing and the increased adoption of potentially carcinogenic habits such as smoking, sedentary lifestyles and an inappropriate diet.2

At least 3.5million people worldwide suffer cancer-related pain on a daily basis.3 About 20% of the pains endured by cancer patients are purely neuropathic in origin, but approximately 40% of cancer patients suffer neuropathic pain if mixed somatic-neuropathic pains are also included.4 Neuropathic pain (NP) is any pain started or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction of the nervous system.5 Cancer patients may experience NP for many reasons, such as the compression or direct infiltration of the tumour into nerve structures, direct nerve trauma resulting from diagnostic or surgical procedures, nerve damage secondary to treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, paraneoplastic neuropathy due to autoimmune mechanisms or a higher incidence of herpes zoster due to immunosuppression.3–6 NP is especially problematic because it is usually suffered in parts of the body that appear anatomically normal, is generally chronic, intense and resistant to commonly used analgesics, is aggravated by phenomena such as allodynia and hyperalgesia and generates high financial costs.3,6

It is necessary to remember that pain in cancer patients is a multidimensional concept, which includes not only the physical perception of pain but also the emotional (anxiety, depression, anger), social and spiritual spheres, as detailed in the total pain concept.7

Health-related quality of lifeThe concept of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) refers to how a person perceives their physical and mental health over time; it is a measure of the disease's impact on the patient, their daily life, their sense of well-being and their functionality.8 HRQoL is an assessment by the patient, not the doctor,8 so it can be easily used by health personnel in order to better understand patients’ needs and thus provide quality care.9 It is so important that the HRQoL evaluation is increasingly included in the protocols of controlled clinical trials as a variable resulting from the proposed interventions.

Thanks to the development of reliable and valid self-administered questionnaires, HRQoL has been evaluated in tens of thousands of patients across a variety of cancers.10 The dimensions in which we seek to quantify HRQoL vary slightly depending on the instrument being used. In general, the following is evaluated8:

- •

Physical functionality: degree to which health limits physical activities.

- •

Emotional functioning: degree to which psychological distress, lack of emotional well-being, anxiety and depression interfere with daily activities.

- •

Social functioning: degree to which health problems interfere with normal social life.

- •

Perceptions of general health and well-being: personal health assessment which includes current health, prospects, and resistance to illness.

- •

Specific symptoms of each disease.

There is evidence that changes in the HRQoL of cancer patients during treatment are statistically significant predictors of survival.10,11 It is extremely important to know the variables that significantly influence the HRQoL of different subgroups of cancer patients. The number of possible determinants of HRQoL is endless, but it has been possible to reduce the list to factors that have regularly shown correlations, such as:

- •

Socio-demographic aspects, such as gender, age, income and support networks.

- •

Those related to cancer, such as type, stage, time since diagnosis and treatment received.

- •

Those related to health, such as comorbidities and nutritional status.

- •

Those related to the patient's lifestyle, such as diet, exercise and alcohol and tobacco use.

This study was designed with the purpose of identifying, through a linear regression model, the main factors determining the HRQoL of patients with cancer-related NP in a tertiary care hospital in the city of Quito.

Materials and methodsAnalytical cross-sectional study. The sample was calculated using the abovementioned prevalence of NP in cancer patients, a confidence level of 95% and a precision of 5%. It comprised 237 patients. Non-probability sampling was carried out for the convenience of patients at the Pain Therapy and Palliative Care Department of the SOLCA Cancer Hospital, in the city of Quito, in the period from January to February 2014. The patients came from outpatient clinics as well as from hospitalisations and emergencies. Patients with NP criteria were included in the study according to the Douleur Neuropathique-4 items (DN4) questionnaire. Patients under the age of 18 years, pregnant women, those with comorbidities potentially causing NP, or with cognitive deficits that hindered their participation were excluded. Patients with a PPS (palliative performance scale) score ≤40 points, for whom a drastic decrease in HRQoL is expected, and those who did not voluntarily agree to participate in the study by signing an informed consent form were also excluded.

Instruments and variablesThe patients’ gender, age, type of cancer, stage and time since diagnosis in months were recorded from their medical histories. Investigators were trained on the standardised application of the following instruments for the collection of additional variables:

- •

DN4 questionnaire for NP detection. Sensitivity of 79.8% and specificity of 78% for results >4.12

- •

Visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain intensity, from 0 to 100.

- •

PPS scale for degree of physical functionality, from 50 to 100.13

- •

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS): a reliable tool for the detection of depression and anxiety states in hospital settings and the measurement of the severity of the emotional disorder.14

- •

Validated SF-36v2 questionnaire™ in Spanish: measures HRQoL in two components: physical and mental. It also provides scores in four domains that make up each component: physical functionality, physical role, body pain and general health (physical component); vitality, social functionality, emotional role and mental health (mental component). Each domain and each component is scored from 0 to 100, and the values closest to 100 are those that best indicate HRQoL.15

A database was created in Excel with the information obtained from each patient, which was exported to the SPSS 17.5® program for statistical analysis. According to the literature reviewed16,17 and the objectives proposed for this research, the analysis comprised three stages:

- •

Descriptive. Details of the clinical and demographic characteristics of the sample and scores of the instruments applied.

- •

Correlational. Correlation coefficients (r) between independent variables and HRQoL: Pearson's rho coefficient was used for quantitative variables (age, time since diagnosis, pain intensity, PPS, anxiety and depression) and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for qualitative variables (gender, type of cancer, stage of cancer).

- •

Linear regression analysis. With the independent variables that showed strong correlation values in the previous step (r≥0.5), equations were constructed to explain the variance in HRQoL. Statistically significant results were those with a value of p<0.05.

All patients involved in the study expressed their written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the SOLCA Cancer Hospital, Quito Centre. All the research was conducted using the ethical considerations of the Declaration of Helsinki.

ResultsDescriptive analysisThe descriptive analysis of the sample is shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Descriptive analysis of the sample.

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 69 (29.1) |

| Female | 168 (70.9) |

| Type of cancer | |

| Breast | 58 (24.5) |

| Female genitaliaa | 40 (16.9) |

| Lymphatic-hematopoietic | 39 (16.5) |

| Gastrointestinal | 25 (10.5) |

| Other | 75 (31.6) |

| Stage | |

| Yet to be staged | 20 (8.4) |

| I | 12 (5.1) |

| II | 54 (22.8) |

| III | 72 (30.4) |

| IV | 79 (33.3) |

| Age (years) | 56.7±15.7 (57) |

| Time since diagnosis (months) | 45.8±51.4 (24) |

| VAS | 45.1±30 (50) |

| PPS | 87.3±15.5 (90) |

| HRQoL physical component | 39.3±9.1 (39.5) |

| Physical functionality | 52.6±29.2 (55) |

| Physical role | 39.3±33.4 (31.3) |

| Body pain | 43.1±26.6 (41) |

| Overall health | 55.1±22.7 (55) |

| HRQoL mental component | 45.5±13.8 (46.5) |

| Vitality | 57.4±26.5 (62.5) |

| Social functionality | 62.2±34.7 (62.5) |

| Emotional role | 58.8±34.4 (50) |

| Mental health | 61.5±25.1 (60) |

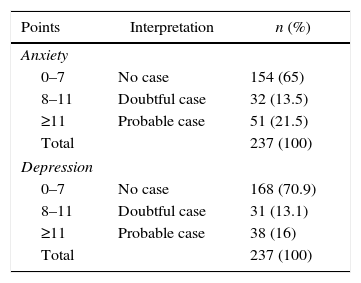

Distribution of the sample according to HADS scores for anxiety and depression.

| Points | Interpretation | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | ||

| 0–7 | No case | 154 (65) |

| 8–11 | Doubtful case | 32 (13.5) |

| ≥11 | Probable case | 51 (21.5) |

| Total | 237 (100) | |

| Depression | ||

| 0–7 | No case | 168 (70.9) |

| 8–11 | Doubtful case | 31 (13.1) |

| ≥11 | Probable case | 38 (16) |

| Total | 237 (100) | |

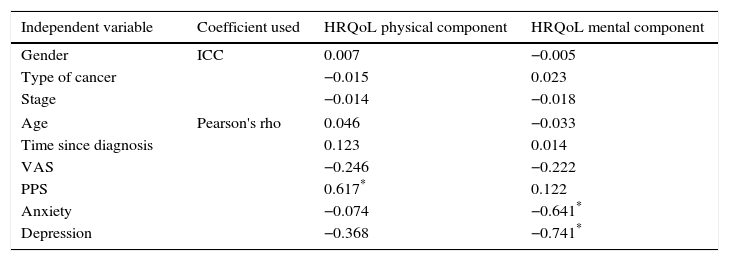

The correlation coefficients (Pearson's rho for quantitative variables and ICC for qualitative variables) between independent variables and HRQoL are presented in Table 3, where those that have an r≥0.5 are highlighted.

Correlation coefficients between independent variables and components of health-related quality of life.

| Independent variable | Coefficient used | HRQoL physical component | HRQoL mental component |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ICC | 0.007 | −0.005 |

| Type of cancer | −0.015 | 0.023 | |

| Stage | −0.014 | −0.018 | |

| Age | Pearson's rho | 0.046 | −0.033 |

| Time since diagnosis | 0.123 | 0.014 | |

| VAS | −0.246 | −0.222 | |

| PPS | 0.617* | 0.122 | |

| Anxiety | −0.074 | −0.641* | |

| Depression | −0.368 | −0.741* | |

ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

Variables with strong correlations (r≥0.5) were taken with the physical and mental components of HRQoL and linear regression equations were used.

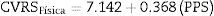

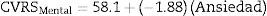

For the physical component of the HRQoL, the model was created with the PPS variable, which obtained Eq. (1)

Eq. (1) explains the 62.5% variance of the HRQoL physical component (r=0.625; p<0.0001). The equation explains that, from an intercept of 7.142 (score of the HRQoL physical component when that of the PPS is 0), each point increment on the PPS scale results in an increase of 0.368 points in the physical component of the patient's HRQoL.

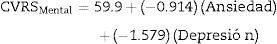

For the mental component of the HRQoL, models were constructed with the anxiety and depression variables, both individually and in combination. Eqs. (2)–(4) were obtained:

Although these three equations were statistically significant (p<0.0001), the one that best explained the variance of the HRQoL mental component is Eq. (4), constructed with the combined anxiety and depression variables, since it explained 77.3% of the variance (r=0.773 versus r=0.619 for (2) and r=0.732 for (3)). The equation explains that, from an intercept of 59.9 (score of the HRQoL mental component when the anxiety and depression scores on the HADS scale are 0), each point increment of the anxiety variable on the HADS scale results in a decrease of 0.914 points in the HRQoL mental component and each point increment of the depression variable on the HADS scale results in a decrease of 1.579 points in the mental component of the patient's HRQoL.

DiscussionThe study population had impaired HRQoL according to the SF-36v2 questionnaire™. The mean HRQoL values in the physical and mental components and their respective domains are lower than those presented by studies performed on the general population in other countries within the region18,19 that used the same instrument. However, the scores obtained are comparable to those of cancer patient populations,20–22 in which there was also a greater alteration of the physical component compared to the mental component, which is similar to what was found in this study.

Reeve et al. performed a two-year follow-up on a population of older adults (n=8592) by measuring their HRQoL at the beginning and end of the period, and found that patients who contracted cancer during that time had a statistically significant decrease in 5 of the 8 domains of the SF-36 questionnaire.22 Meanwhile, Tofthagen et al. established HRQoL in groups of cancer patients with and without NP, and observed a statistically significant decrease in 5 of the 8 domains of the questionnaire among the patients suffering from NP.23 It could be thought then that the decrease in HRQoL among the study population is attributable to the cancer diagnosis, the impact of this disease and the additional deleterious effect of cancer-related NP.

The pain intensity measured with the VAS in the population presented an average score of 45.1±30, which is consistent with values obtained in similar studies conducted on cancer patients that also show higher intensity figures in NP than in somatic pain.23,24 It should be mentioned that this study did not differentiate between the outpatient groups, whose pain was mainly controlled, and those from emergencies and hospitalisations, in whom an important reason for consultation and admission is pain of great intensity. Stage IV was most common in the population; one-third of the population had metastatic disease. This observation is common in groups of patients with cancer-related NP24,25 and is explained by the accumulation of algogenic mechanisms during the natural history of the disease.

Using the HADS questionnaire, a prevalence of probable anxiety and depression cases of 21.5 and 16%, respectively, was found. The literature shows markedly variable values in the prevalence of these psychiatric comorbidities in cancer patients using this instrument. In Spain, Rodríguez-Vega et al.26 reported 15.7% for anxiety and 14.6% for depression, while in Mexico Ornelas-Mejorada et al.27 reported 27 and 28%, respectively. These variations could be explained by socio-cultural factors specific to each country and each population sample.

This study is not the first to identify factors determining the quality of life of cancer patients. Previous works have sought to correlate the HRQoL of these patients with clinical (stage, type of cancer, time since diagnosis, type of treatment received), demographic (age, gender) and socio-economic (monthly family income, level of education, marital status, employment situation, health insurance) variables, as well as with religiousness and spirituality. In this population, no correlation was found between HRQoL and age, gender, stage, type of cancer, time since diagnosis or pain intensity. The literature has not shown gender to correlate with the HRQoL of cancer patients,21,28,29 while the role of age is a subject of dispute: in some studies HRQoL improves with age,28 in others the opposite occurs21 and in others no significant correlations are found.

The lack of correlation between HRQoL and cancer-related variables (type, stage, and time since diagnosis) can be explained by the fact that at all times of the disease there are factors that affect HRQoL in one way or another. The very moment of diagnosis, the initial stages of treatment and the months following the end of treatment are hard times for the patient both physically and emotionally.30 Towards the final stages of the disease, the physical limitations and cumulative side effects of the treatment contribute to a decrease in well-being. This observation has been confirmed in studies on patients with ovarian cancer31 and cancer patients in palliative care.21

The patient's physical functionality measured with the PPS scale is the only variable that presented a strong correlation with the physical component of HRQoL and with which a statistically significant linear regression equation was established (p<0.001). This highlights the importance of medical interventions that seek to preserve the functionality of cancer patients, including adequate pain management and comprehensive palliative care for patients who require it.

The only variables that correlated with the mental component of HRQoL were the psychiatric comorbidities studied (anxiety and depression). The linear regression model constructed with both explained the 77.3% variance in the mental component of HRQoL (p<0.001). The influence of these two comorbidities on HRQoL has been described previously in both cancer and non-cancer patients. High prevalences of anxiety and depression have been observed as predictors of poor quality of life among patients with thyroid cancer,32 breast cancer,33 head and neck cancer34 and cancer in general.35,36 Similar observations have been found in groups of patients with various chronic pain aetiologies37 and other chronic diseases.38

Possible relationships between chronic diseases such as cancer and anxiety and depression have been analysed before. A systematic review and meta-synthesis on the subject38 shows that most studies have found that patients tend to suffer from depression or anxiety as a result of being diagnosed with a chronic disease. Multiple consequences of diagnosis can contribute to this fact: loss of sense of self, anxiety and uncertainty about the future (given the unpredictability and incurable nature of the disease and its relationship to death), loss of relationships and social isolation, feelings of guilt, limitations produced by the illness itself, sadness due to the changes occurring in their life. Other studies describe a second pathway in which certain patients describe pre-existing emotional conditions, such as anxiety and depression, as the cause of their chronic illness. For example, the patient who sees their anxiety and permanent stress of their lifestyle as the cause behind their hypertension. Finally, other authors propose a third way in which chronic illness and anxiety/depression are circumstances that maintain a cyclical relationship, where each one reciprocally feeds off the other. Whatever the relationship between anxiety/depression and chronic diseases, their impact on HRQoL is evident.

Anxiety and depression explain a lower HRQoL (mainly in the mental component) due to several factors39–41:

- •

Depressed patients maximise the impact of their physical limitations on their daily activity. Those without depression manage to look beyond these limitations to maintain a functionality close to what they typically had before.

- •

As explained in the total pain concept, anxiety and depression can significantly play a part in increasing the intensity with which pain is perceived.

- •

Depressive ideas and feelings are related to social isolation and diminished interpersonal relationships. The patient's family and friends are their main support network, which is eliminated when the patient is isolated voluntarily.

- •

Anxiety and depression make the patient self-evaluate their health as poor and with a tendency to worsen, and become set on an inevitable scenario of death.

- •

Depression intensifies the perception of feelings of tiredness and exhaustion, which impacts on the subjective well-being of patients in the vitality domain.

One barrier to comprehensive cancer care is the “normalisation” of anxiety and depression by both the doctor and the patient. It is so common to find symptoms of anxiety and depression in a cancer patient that the doctor begins to see it as a normal and inevitable component of the disease, so does not consider its independent management necessary. Another obstacle to diagnosis is that cancer and depression are diseases with common symptoms (mainly fatigue and pain), so it is common to exclusively attribute them to the cancer and forget about the possible contribution of psychiatric comorbidities.39 Moreover, the patient fears the formal diagnosis of anxiety and depression due to the social stigma accompanying mental illness. Rarely do they consider psychiatric help necessary, considering that treating these disorders is neither essential nor a priority.40

ConclusionsThis study highlights the need for comprehensive cancer care to include the timely detection and management of psychiatric comorbidities as well as professional psychological support during all stages of the disease. Evidence is provided of the fact that this practice could have considerable favourable effects on the preservation of HRQoL among these patients.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank Dr Marcos Serrano and Dr Carmen Elena Cabezas and the staff at the Pain Therapy and Palliative Care Department of the SOLCA Hospital, Quito Centre, for their participation in conducting the research and their report. We would also like to thank QualityMetric Inc. for the licence received to use the SF-36v2 questionnaire™.

Please cite this article as: Gordillo Altamirano F, Fierro Torres MJ, Cevallos Salas N, Cervantes Vélez MC. La salud mental determina la calidad de vida de los pacientes con dolor neuropático oncológico en Quito, Ecuador. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2017;46:154–160.

Article based on the degree thesis entitled “Factors determining quality of life in patients with cancer-related neuropathic pain whose PPS (Palliative Performance Scale) score is higher than 40 at the SOLCA (Society for the Fight Against Cancer) Hospital, Quito Centre, in the period from January to February 2014”, presented at the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador in 2014.