To describe haematological adverse effects in adolescents with anorexia nervosa who are taking olanzapine.

MethodsCase series report.

Case reportThe reported cases (two female patients and one male) were found to have blood test abnormalities after starting olanzapine and to rapidly recover their platelet and neutrophil values after the drug was discontinued. Low haemoglobin values persisted longer than observed in other series. These abnormalities became more noticeable when the dose of olanzapine was increased to 5 mg/day (initial dose 2.5 mg/day). It should be noted that two of the patients already had values indicative of mild neutropenia before they started the antipsychotic drug, and that these worsened as they continued taking the drug. In one of the patients there was only a decrease in neutrophil values, as well as mild anaemia.

ConclusionsThis first case series of haematological abnormalities in adolescents with anorexia nervosa who are taking olanzapine found values corresponding to pancytopenia in two of the three cases reported. It would be worthwhile to consider heightening haematological surveillance in this population when starting treatment with olanzapine and rethinking our knowledge regarding the frequency of these side effects.

Describir los efectos adversos hematológicos en adolescentes con anorexia nerviosa que toman olanzapina.

MétodosReporte de serie de casos.

Reporte de casoEn los casos reportados (2 mujeres y 1 varón) se evidenciaron alteraciones de las series sanguíneas tras el inicio de olanzapina y una recuperación rápida de los valores de plaquetas y neutrófilos tras la suspensión del fármaco. Los valores bajos de hemoglobina persistieron más que en las otras series. Dichas alteraciones se hicieron más ostensibles al incrementarse la dosis de olanzapina a 5 mg/día (dosis inicial, 2,5 mg/día). Cabe resaltar que antes del inicio del psicofármaco 2 de los pacientes ya tenían valores en la banda de la neutropenia leve, que fueron empeorando a medida que se instalaba el antipsicótico. En uno de los pacientes solo se redujeron los valores de neutrófilos junto con anemia leve.

ConclusionesEste es el primer reporte de casos de alteraciones hematológicas en adolescentes con anorexia nerviosa que toman olanzapina, y se hallaron valores de pancitopenia en 2 de los 3 casos estudiados. Se debería considerar una mayor vigilancia hematológica en dicha población al iniciar el tratamiento con olanzapina y replantear nuestros conocimientos en cuanto a la frecuencia de dichos efectos secundarios.

When adolescent patients with anorexia nervosa are very agitated or resist refeeding, olanzapine is one option that can be used.1 However, as is already known, the risk of adverse effects among the paediatric and adolescent population is greater than among adults. Most adverse effects associated with olanzapine are not serious, but some could be life threatening, such as blood dyscrasia, and leucocytopenia and agranulocytosis occur in 1/10,000 treated patients.2

Several studies have been published regarding haematological disorders in patients with anorexia. Miller et al.3 found the following prevalences in a community-based study of 215 women with anorexia: anaemia 39%; thrombocytopaenia 5%; and leucocytopenia 34%. A study review by Hutter et al.4 reported the following prevalences in patients with anorexia nervosa: anaemia 21–39%; leucocytopenia 29–39%; and thrombocytopaenia 5–11%.

In the study by De Fillipo et al.5 in 2016, it was found that, of a population of 318 patients with anorexia, 16.7% had anaemia, 7.9% had neutropenia and 8.9% had thrombocytopaenia. The combination of 2 types of cytopenia was present in 8.7% of patients (anaemia and neutropenia 3.8%, anaemia and thrombocytopaenia 2.6% and neutropenia with thrombocytopaenia 2.3%); pancytopenic patients represented only 1.1% of the whole population.

More recently, Walsh et al.6 have found that, in a population of 798 patients with anorexia nervosa, 16.4% of patients with AN-R (restricting subtype of anorexia nervosa) and 20.2% of patients with AN-B/P (binge-eating/purging subtype of anorexia nervosa) had anaemia. Thrombocytopaenia was present in 7.4% of those with AN-R and 5.2% of those with AN-B/P. Leucocytopenia was present more often in patients with AN-R (50.5%) than patients with AN-B/P (36.8%) (p < 0.001).

Haematological disorders in patients treated with psychotropic drugs are varied. Amongst psychoactive drugs, antipsychotics, including not only clozapine but also olanzapine, and phenothiazines such as chlorpromazine, are the most common causes of neutropenia and agranulocytosis.

Without a doubt, the drug most commonly associated with neutropenia and agranulocytosis is clozapine, an antipsychotic linked to agranulocytosis that requires haematological monitoring during its use. The first reports of this effect date back to 1977, with the research conducted by Amsler et al., and reports have been repeated in several countries.

Several case reports have emerged regarding olanzapine and its potential to cause haematological side effects. Cases of leucocytopenia, anaemia, thrombocytopaenia, pancytopenia and eosinophilia have been published. The majority of papers have focused on describing neutropenia in patients with olanzapine. Kodesh et al.7 report three cases of patients who developed dose-dependent leucocytopenia, suggesting that the dose of olanzapine should be reduced. However, both Steinwachs et al. and Meissner et al. each report two cases of olanzapine-induced leucocytopenia, which reversed when the drug was discontinued, and one of the cases presented with haematological disorders when re-exposed to the drug.8,9 Buchman et al. report a case of febrile neutropenia that resolved after immediate discontinuation of the drug.10

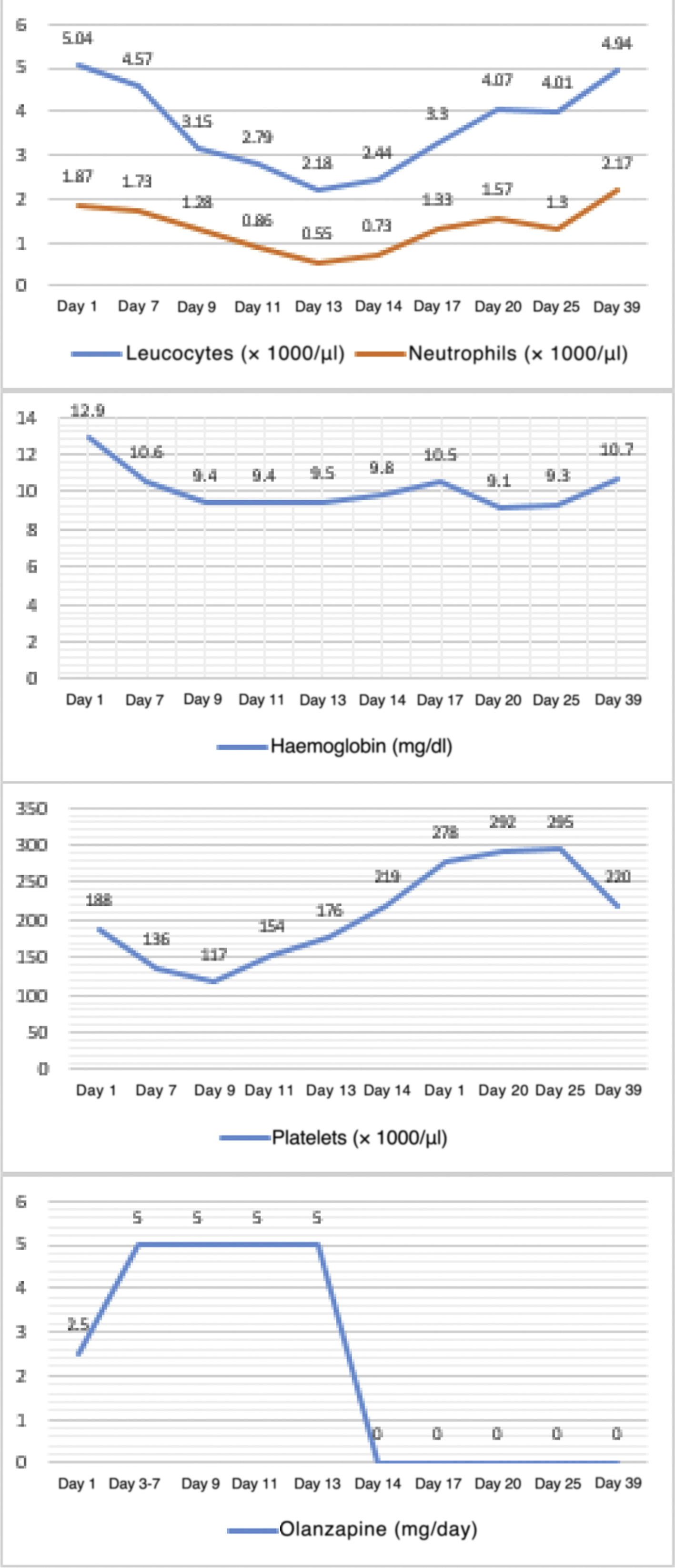

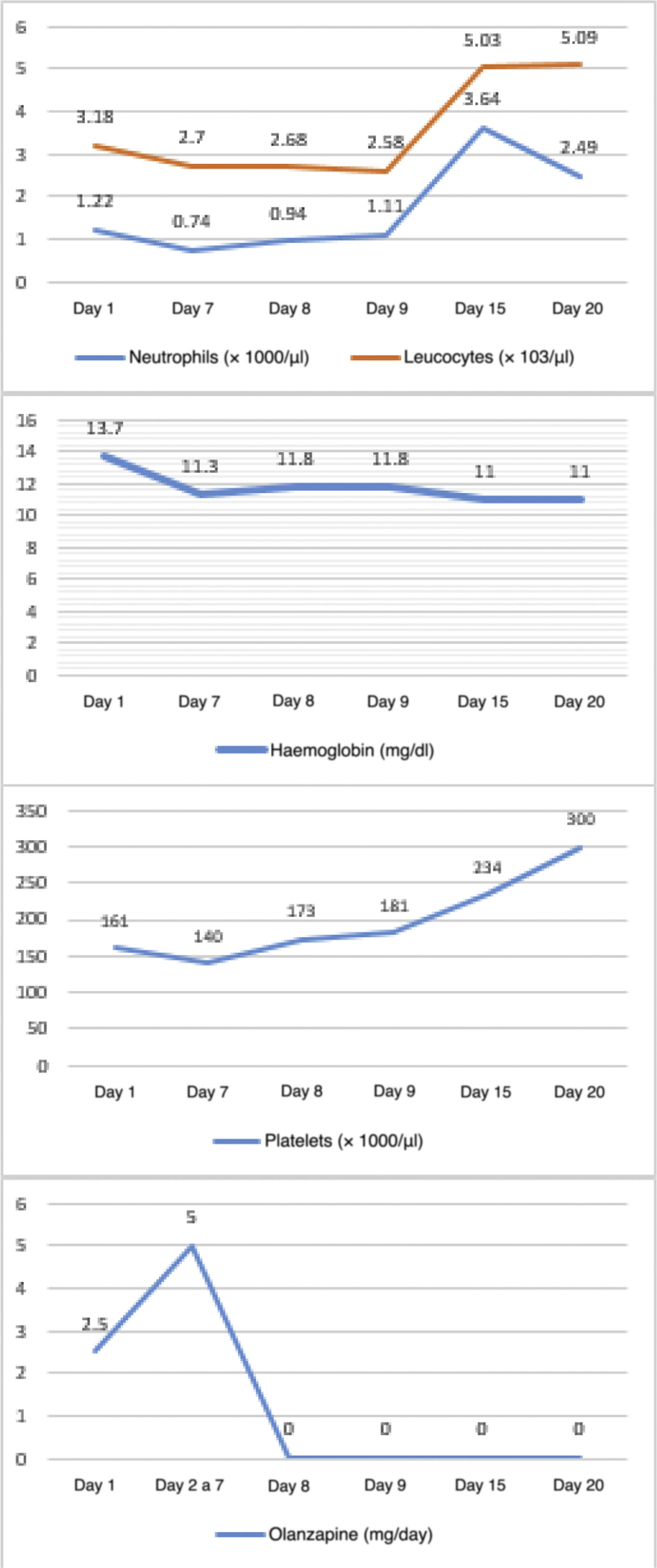

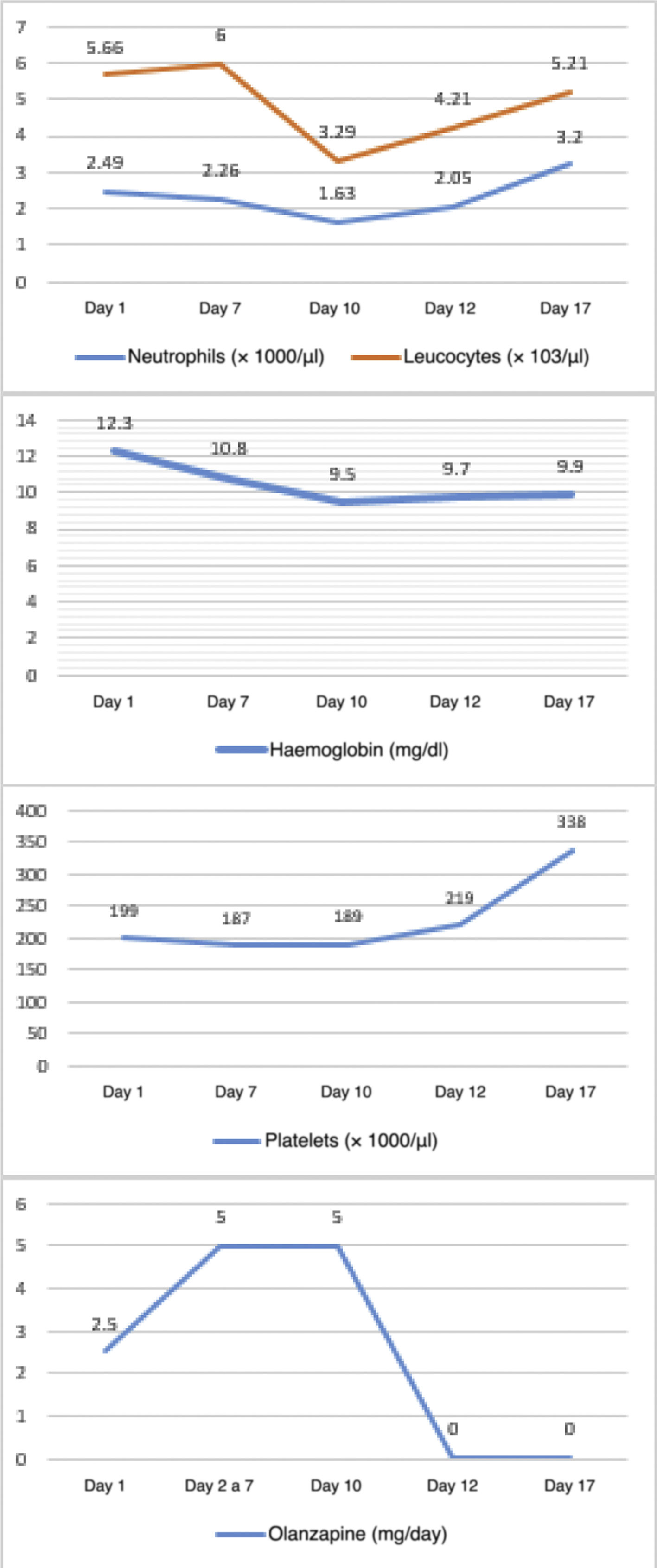

The objective of this study is to look at 3 case reports of haematological adverse effects due to olanzapine in adolescent patients diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, to describe their characteristics and to highlight the importance of such adverse effects in the affected population in order to take the corresponding preventive measures.Case 1 12-year-old female adolescent with onset of anorexia nervosa symptoms 3 months prior to admission. She came in due to depressive symptoms and worsening of dietary restriction. She was treated with sertraline, topiramate and clonazepam for 3 months, with poor response. On physical examination, she appeared very thin but was haemodynamically stable. On mental examination, she was conscious, oriented, with low mood and overvalued ideas of guilt and body image misconception, with no psychotic symptoms. She demanded that she be discharged and had low frustration tolerance and no awareness of illness. A baseline blood count was taken: haemoglobin 12.9 g/dl, white blood cells 2.89 × 103/µl, neutrophils 1.87 × 103/µl and platelets 188 × 103/µl, showing leucocytopenia with mild neutropenia. Olanzapine was started at 2.5 mg/day with sertraline at 50 mg/day. On day three, the dose of olanzapine was increased to 5 mg/day. A follow-up blood count on day 7 showed haemoglobin 10.6 g/dl, white blood cells 4.57 × 103/µl, neutrophils 1.73 × 103/µl and platelets 136 × 103/µl. On day 9, another follow-up blood count showed pancytopenia: haemoglobin 9.4 g/dl, white blood cells 3.15 × 103/µl, neutrophils 1.28 × 103/µl and platelets 117 × 103/µl. On day 12, it was decided to discontinue olanzapine due to a third complete blood count with haemoglobin 9.4 g/dl, white blood cells 2.79 × 103/µl, neutrophils 0.86 × 103/µl and platelets 154 × 103/µl. The following day, the reduction in white blood cells (2.18 × 103/µl) and neutrophils (0.55 × 103/µl) was even greater. However, by day 14, the white blood cells and platelet parameters had improved. Multiple subsequent follow-ups were performed, and on day 25 a blood count showed the following results: haemoglobin 9.3 g/dl, white blood cells 4.01 × 103/µl, neutrophils 1.3 × 103/µl and platelets 295 × 103/µl. It was decided to add aripiprazole at 2.5 mg/day. On day 39, the white blood cell count had normalised but anaemia persisted. The patient was discharged on day 44 with mild anaemia and receiving nutritional treatment, vitamins and antipsychotics (sertraline 50 mg/day, aripiprazole 2.5 mg/day and clonazepam 0.75 mg/day (Fig. 1). Haematological changes and olanzapine doses in Case 1. A 12-year-old female adolescent who had anorexia nervosa 9 months before admission came in due to decreased food intake, which had become more evident over the last 4 months, weight loss of approximately 8 kg, amenorrhoea and a low mood. She has no other significant medical history. She was admitted with a body mass index (BMI) of 12.75 and was haemodynamically stable. On mental examination, she was conscious, oriented and not very approachable. She did not make eye contact with the interviewer, had stilted speech, conservative thinking with cognitive distortions and body image misconception. She showed no psychotic symptoms. She had low frustration tolerance and appeared irritable when confronted about her food intake, with partial awareness of mental illness. Her blood count results on admission were haemoglobin 13.7 g/dl, absolute white blood cell count 3.18 × 103/µl, neutrophils 1.22 × 103/µl and platelets 161 × 103/µl, showing leucocytopenia with mild neutropenia. Olanzapine was started at 2.5 mg/day with sertraline at 50 mg/day. From days 2–7, the dose of olanzapine was increased to 5 mg/day. On day seven of hospitalisation, her follow-up blood count showed mild anaemia with haemoglobin of 11.3 g/dl, leucocytopenia 2.7 × 103/µl, moderate neutropenia with neutrophils 0.74 × 103/µl and thrombocytopaenia with platelets 140 × 103/µl. An assessment by a paediatric haematologist suggested, as a first possibility, that it was secondary to drugs, and therefore it was decided to stop olanzapine and perform more frequent follow-up blood counts. On day 8 of hospitalisation, results showed haemoglobin 11.8 g/dl, white blood cells at 2.5 × 103/µl, neutrophils 1.11 × 103/µl and platelets 181 × 103/µl. By day 15 (7 days after stopping olanzapine), an increase in her white blood cell count and platelet count was evident, although her haemoglobin remained low. It was decided to discharge the patient with nutritional treatment, antidepressants and vitamins. Four days after discharge, a follow-up blood count was performed, showing the persistence of normal white blood cell and platelet counts but with mild anaemia (Fig. 2). Haematological changes and olanzapine doses in Case 2. A 14-year-old male adolescent with a 12-month history of anorexia nervosa came in due to marked weight loss, loss of appetite and body image misconception. He was doing strenuous exercise and following restrictive diets. On mental examination, he was conscious and oriented, with body image misconception, restricted affect, euthymic mood, bradypsychia and with no awareness of illness. His blood count on admission showed haemoglobin 13.9 g/dl, white blood cells 5.66 × 103/µl, neutrophils 2.49 × 103/µl and platelets 199 × 103/µl. Olanzapine was started at 2.5 mg/day with sertraline at 50 mg/day. On day three, the dose of olanzapine was increased to 5 mg/day. On day seven of hospitalisation, a follow-up blood count showed haemoglobin 12.3 g/dl, white blood cells 6 × 103/µl, neutrophils 2.26 × 103/µl and platelets 187 × 103/µl. On day 10, before increasing the dose of olanzapine, a new follow-up blood count was ordered, which showed haematological abnormalities (haemoglobin 10.8 g/dl, white blood cells 3.49 × 103/µl, neutrophils 1.63 × 103/µl and platelets 189 × 103/µl). In the short term, this could generate a significant disorder, such as neutropenia, so it was decided to stop the antipsychotic. On day 12, the white blood cell count and platelet count improved, although anaemia persisted (haemoglobin 9.7 g/dl, white blood cells 4.21 × 103/µl, neutrophils 2.05 × 103/µl and platelets 219 × 103/µl), so it was decided to start him on another antipsychotic (risperidone). The blood count showed no further abnormalities, although the anaemia persisted (Fig. 3). Haematological changes and olanzapine doses in Case 3.

Although it is true that there are multiple case reports of haematological disorders in adults taking olanzapine, there are few articles on this risk in adolescents, and there are none that specifically investigate these effects in patients with an eating disorder. Research by Kodesh et al.7 reports the case of a schizophrenic adolescent patient who developed neutropenia after starting olanzapine. This decrease in neutrophils was transient and the study drug was not stopped. Dugal et al.11 report olanzapine-induced neutropenia in an adolescent with bipolar disorder. Freedman et al.12 also present the case of a psychotic adolescent who developed olanzapine-induced agranulocytosis.

Cases of pancytopenia have been reported in adults. Onofrj et al.13 and Maurier et al.14 reported cases of pancytopenia in adults treated with olanzapine. In 2017, Pang et al.15 reported the case of a 50-year-old schizophrenic man who developed pancytopenia after starting olanzapine.

If we consider the first patient in our series, it can be seen that, before starting the antipsychotic, she already had leucocytopenia and mild neutropenia, both of which rapidly worsened after starting olanzapine (2.5 mg/day), and her red blood cell and platelet counts also deteriorated. It should be noted that, upon increasing the dose to 5 mg/day, deleterious effects in all three cell lines became more intense. The greatest decrease observed was in white blood cells (up to a moderate neutropenia), while the anaemia and thrombocytopaenia were mild. Platelet and neutrophil counts rapidly recovered after stopping the drug. Low haemoglobin values remained abnormal until the moment of discharge.

In the second patient, baseline neutropenia was also observed. After starting the antipsychotic, the platelet count and haemoglobin level decreased, while neutropenia values fell to a moderate level. It should be noted that, as in the first case, the first cell line to recover was that of the platelets, followed by neutrophils, and the patient continued to have a mild anaemia up to discharge.

In the third patient, tests initially showed normal values in all 3 cell lines. During administration of the drug, a decrease in neutrophil levels was observed, without reaching the levels required for neutropenia. A mild anaemia appeared.

Drug-induced neutropenia usually manifests after 1–2 weeks of exposure. The degree of neutropenia that develops depends on the dose and duration of the exposure. Agranulocytosis usually appears 3–4 weeks after starting treatment and is more common, and tends to be more severe, in the elderly. In our case reports under study there were no cases of agranulocytosis.

The white blood cell count usually recovers within 34 weeks of stopping treatment. In our case reports, white blood cell counts recovered after 12–39 days. As in most reported cases, haematological adverse effects occurred during the first month of treatment with olanzapine. The most significant decrease in values was between 7 and 14 days after starting treatment. In no case was there a need for colony-stimulating factors and both the white blood cell count and the platelet count returned to normal after stopping olanzapine. It is important to highlight the delay in reaching normal red blood cells levels in all 3 patients.

It can be concluded that haematological adverse effects after administration of olanzapine worsened in 2 of our patients since these adolescents had low baseline white blood cells and neutrophil counts. It can be understood that these initial abnormalities may be related to the underlying disease, but it is evident that the decrease in values is related to olanzapine. The three patients had abnormal red blood cell counts and 2 of them also had mild thrombocytopaenia. In two of the patients, the diagnosis was pancytopenia.

The need for haematological monitoring should be considered not only at the start of treatment, but also during the first and second weeks after starting the antipsychotic regimen, in order to detect these complications, which may be life-threatening and apparently underestimated, early.

FundingThe report was funded by the authors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.