Chronic diseases are a public health problem, and 80% of them are related to modifiable risk factors such as unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, smoking, and risky alcohol consumption. Although the intervention in smoking and hazardous alcohol drinking has proven to be effective in Primary Care, it is unknown whether it works in the same way in the hospital setting.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the effectiveness of brief counselling in order to modify the stage of change in smokers and at-risk drinkers treated in a high complexity hospital.

MethodsA Randomised controlled trial to be conducted, in which an evaluation is made of four brief counselling strategies for smoking cessation and risky alcohol consumption compared to usual care, selected according to the patient’s stage of change. The primary result will be the proportion of patients in each of the groups (intervention and control) with identified progress in the stage of change. The reduction of consumption will be also be analysed. Protocol registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03521622).

ResultsThe results will be published in scientific journals, and its application aims to generate behavioural intervention protocols for modifiable risk factors in high complexity hospitals. The trial was presented and approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and Hospital Universitario de San Ignacio, Bogota, Colombia (Approval 01/2018).

Las enfermedades crónicas son un problema de salud pública; el 80% de ellas se relacionan con factores de riesgo modificables, como una dieta poco saludable, la inactividad física, el tabaquismo y el consumo riesgoso de alcohol. La intervención en el tabaquismo y el consumo riesgoso de alcohol se ha demostrado efectiva en el cuidado primario, pero se desconoce si funciona de la misma manera en el contexto hospitalario.

ObjetivoEvaluar la efectividad de la consejería breve para modificar el estadio de cambio en pacientes fumadores y bebedores en riesgo atendidos en un hospital de alta complejidad.

MétodosExperimento clínico aleatorizado, que evalúa la efectividad de 4 modalidades de consejería breve para la cesación de tabaquismo y el consumo riesgoso de alcohol en comparación con el cuidado habitual, seleccionadas según el estadio de cambio del sujeto. El resultado primario es la proporción de pacientes en cada uno de los grupos (intervención y control) en los cuales se identifica el avance en el estadio de cambio; además se analizará la reducción de consumos. Protocolo registrado en ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03521622).

ResultadosLos resultados se publicarán en revistas de literatura científica y su aplicación pretende generar protocolos de intervenciones conductuales en factores de riesgo modificables en hospitales de alta complejidad. El experimento fue presentado y aprobado por el Comité de Ética e Investigación de la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana y el Hospital Universitario de San Ignacio (aprobación 01/2018).

Cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory diseases affect both morbidity and mortality rates in low- and middle-income countries1; these diseases are responsible for over 75% of deaths (32 million) worldwide.2 In 2016, the likelihood of dying from these causes between the ages of 30 and 70 was approximately 18%.3 In Colombia, the main causes of death of people over 45 years of age are also chronic non-communicable diseases, such as coronary heart disease, cancer (of the stomach, breast and uterus), cerebrovascular disease and diabetes.4

There are risk factors that contribute to the development of these diseases and lead to an increase in morbidity and general mortality rates.1 The evidence particularly points to smoking, physical inactivity, and the harmful use of alcohol as having a significant impact on the burden of disease.2 Smoking (including second-hand smoke) causes more than 7.2 million deaths a year, and it is estimated this figure will increase exponentially in the coming years,5 due to its direct relationship with cardiovascular disease and cancers.6 The harmful use of alcohol causes approximately 3.3 million deaths annually worldwide (5.9% of all deaths),7 and more than half are due to chronic diseases.2

In 2004, the World Health Organisation (WHO) developed and evaluated a series of guidelines for health promotion in hospitals, and recommended that health promotion and disease prevention interventions be carried out at all contacts between healthcare institutions and patients.8 It is known that hospitalised patients have health needs (related or not to the cause of admission), which can be addressed in this context, as, for a range of different reasons, they may be more receptive to change while in hospital.8,9 However, clinical interventions aimed at modifying risk behaviours in patients who engage in them are not considered a priority in the hospital setting, and the opportunity to act is often lost.8

There is evidence of the efficacy of behavioural interventions in the outpatient setting. For example, in the treatment of smoking cessation, counselling, in conjunction with drug-based interventions, achieves cessation rates close to 30%.10 For alcohol consumption, brief counselling interventions have been shown to decrease the number of standard drinks per week (mean reduction, −2.5; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], −3.8 to −1.21), the number of episodes in which safe alcohol limits are exceeded (odds ratio [OR] = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.53−0.67; I2 = 24%) and episodes of heavy alcohol consumption (OR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.58−0.77; I2 = 24%).11–13 However, very few studies have been carried out in the hospital setting, and the results available are conflicting. This is despite the fact that it should be easier for patients to receive interventions in this setting simply because, with them being under medical care for longer, brief interventions on reducing consumption could have optimal results.14

Promoting brief interventions to modify risk behaviours in the hospital setting as an initial phase for the treatment of smokers and risky alcohol consumers does seem like a sensible idea. However, there have been very few studies to corroborate the efficacy of these interventions.15–18 Therefore, the purpose of this work is to assess the effect of a brief intervention on the stage of change in risk behaviours, prescribed according to the individual risk profile and aimed at improving each person's phase or stage.

ObjectivesThe primary objective is to identify the effect of a brief counselling intervention for smoking cessation in patients who smoke, and reduction of risky alcohol consumption in patients who drink alcohol. The secondary objective is to analyse the effect of behavioural interventions to reduce or stop smoking and alcohol consumption at one and three months after the intervention.

MethodsThe study is a randomised controlled superiority clinical trial comparing the use of brief behavioural counselling interventions tailored to a patient's risk factors (active smoking or risky alcohol use, or dual if individuals have both risky behaviours) versus usual care (written educational intervention from the Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection).19

The project is carried out at the San Ignacio University Hospital, which provides highly complex care services in the city of Bogotá, Colombia.

Eligibility criteriaMen and women aged 19–64 undergoing diagnostic and surgical procedures in the hospital setting will be included. One more of the following risk factors will be considered: current smoking (of any number of cigarettes or other sources of tobacco, such as pipe, tobacco, hookah, etc., in the last month or >100 cigarettes in their lifetime); at-risk consumer of alcohol (in women, daily consumption of four or more standard drinks and five or more in men, at least once in the last 12 months) and an Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDI)20 score between 8 and 15. Subjects with a fixed address and contact telephone number, and willingness to participate in telephone follow-up for three months, will be included. Patients with previous or ongoing tobacco cessation or alcohol use disorder treatment, a history of neurological or psychiatric diseases, sensory deficits, language disorders or any comorbidity that affects the subject's willingness to receive the counselling intervention will not be considered as participants. Also excluded will be people with a use disorder involving alcohol or other non-tobacco psychoactive substances, who are taking part in action and maintenance stages of change against their risk factor (i.e. those already modifying the risk).21

Participants will be identified from the scheduling lists for surgery and diagnostic procedures in the different hospital departments, and will enter the study from the surgical, obstetrics and orthopaedics wards or from departments performing planned diagnostic procedures. In addition, subjects who attend for outpatient surgery programming will be considered, taking advantage of the waiting time during their procedure. Compliance with the eligibility criteria of the study will be verified and they will be invited to take part after signing the informed consent form.

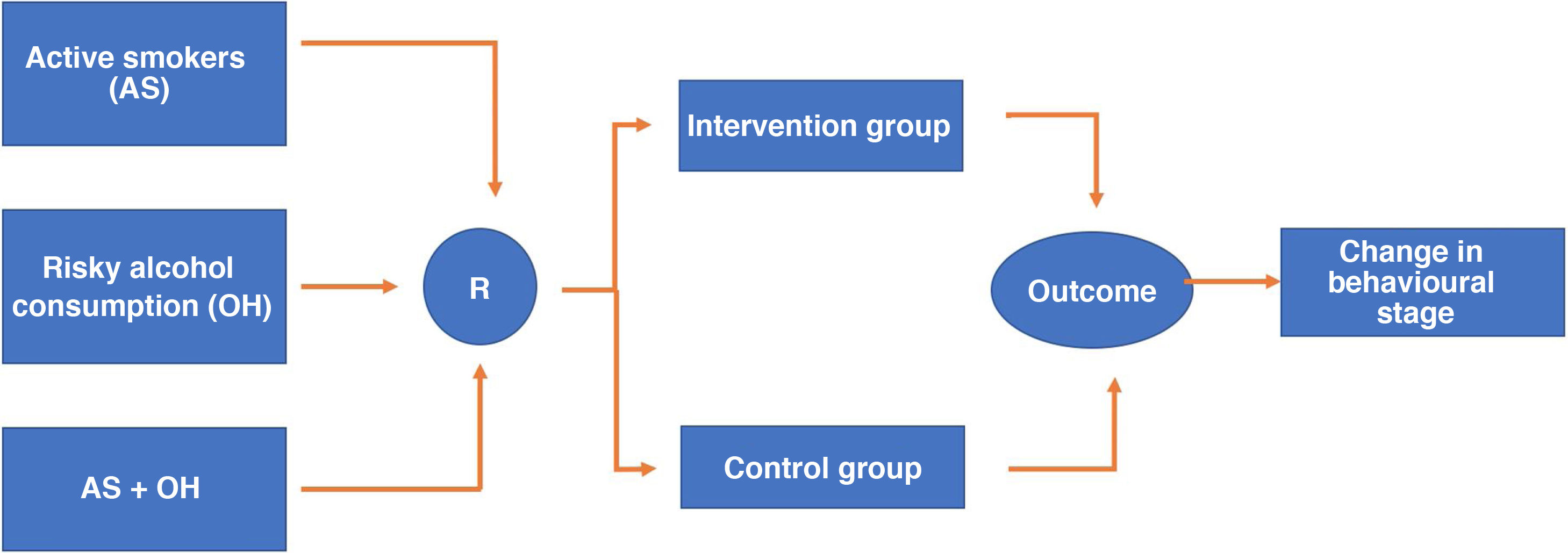

RandomisationResearch Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) version 7.3.6. of 2019 will be used as software for electronic data collection. This software enables the randomisation sequence to be programmed which in this case will be 1:1 to place the participants in each of the two arms of the study (intervention and control). Randomisation will be stratified according to whether the individual is an active smoker (stratum 1), a risky alcohol user (stratum 2) or has both risk factors simultaneously (stratum 3), and to maintain the balance between the strata, assignment will be programmed in blocks of eight participants within each stratum (Fig. 1). Redcap allows the predetermined randomisation sequence to remain hidden from both the people responsible for the randomisation procedure, which in our case will be the staff who will fill in the sociodemographic and clinical information collection questionnaire, and those who carry out the interventions. After completing the above questionnaire, the randomisation tab is activated, and the system will make the assignment without any possibility of this procedure being manipulated.

InterventionsBrief behavioural interventionThis consists of a session with a structured conversation (approximately 5−15 min) about the risk factor, taking into account the patient's stage of change at the time of study entry. In patients with a smoking risk factor and motivation to change (contemplation or preparation phase, depending on the phases of the change stage),21 the Five "As" strategy will be used (ask, advise, assess, assist, arrange).22 For patients not motivated to change (precontemplation phase),21 a motivational approach will be used with the Five "Rs" model (relevance, risks, rewards, roadblocks, repetition).22,23 In patients with the risk factor of risky alcohol consumption motivated to change, the simple advice strategy will be used (introduction in relation to the topic, feedback with their AUDIT score, informing them in a clear, firm and personalised manner about the risks, giving advice regarding the limits of consumption and the meaning of a standard drinking unit, setting goals to reduce consumption and agreeing on follow-up).24 For those not motivated to change, a brief motivational interview-based approach will be used, initially aimed at achieving a bond with the participant and creating an environment conducive to introducing the topic. Subsequently, the focus is on clarifying the objective of the intervention, evoking the motivation and discourse for change, and finally, where possible, goals and objectives are planned.25

A week after the initial intervention, a second brief telephone reinforcement session will be held. The same call will be made to the patients in the control group in order to verify that they received the written material.

Follow-upParticipants in both groups will be followed up by telephone calls one and three months after the initial intervention, using a standardised questionnaire applied by a qualified nurse trained in its completion. The primary outcome (progress in the stage of change) reported by the participant will be enquired about, and their answers regarding their intention to change the risk factor in question (smoking or alcohol consumption) will be used to complete the short version of the Prochaska and DiClemente stages of change questionnaire.26,27 Progress is considered positive if the participant previously in the precontemplation category (the one who is not motivated or is not thinking about stopping smoking or reducing alcohol consumption) advances to contemplation or preparation (has some motivation and is seriously thinking about stopping smoking or cutting down on alcohol in the next month or six months) and those in contemplation or preparation (some motivation) move to action (already making the change). For the assessment of the secondary outcome, the frequency and intensity of smoking and alcohol consumption will be investigated. Cessation is defined as not having had any number of cigarettes or other sources of tobacco after their hospitalisation, and compliance with low-risk alcohol consumption as having consumed less than 3/4 (females/males) standard drinks per occasion in that same period.

Education and training of healthcare professionalsThe GPs who are going to carry out the interventions will be provided with training for six months (two hours per week; 48 h in total) before the execution phase of the project. The training includes a theoretical review of brief counselling interventions for smoking cessation and the reduction of risky alcohol consumption, along with practical sessions observing a doctor, expert in the interventions being evaluated (50 h of training, nine years of experience). Practical exercises will then be carried out to develop skills in this type of intervention with simulated patients. Forms will be used to verify the adherence to and quality of the interventions and optimal performance will be considered a score ≥4.5/5 in the aforementioned instrument. If they do not obtain the above score, they will retrain until they achieve the optimal score.25 After completion of the training workshops, the clinicians will be certified as competent to carry out the different brief interventions. In addition, practical reinforcement sessions (one hour twice a week) will be carried out with real patients for two months.

Data collection and systematisationStandardised forms previously prepared by the researchers will be used for the collection and recording of the data of interest for the study. The information will be recorded in the REDCap software (licence registered by the San Ignacio University Hospital) (Table 1).

Study variables.

| Dependent variable | Progress in the stage of change in risk behaviours (phases of precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action and maintenance) | |

|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | PersonalAgeGenderMarital statusSocio-economic stratumEducational levelDegree of awareness of the benefits of the changeDegree of motivation to changeDegree of perceived self-efficacyPrevious attempts to change the risk factorNumber of pack-years for smokersLevel of physical dependence on nicotineRisk zone regarding alcohol consumption | RelativesType of familyFamily life cycleFamily functioning |

| Confounding variables | Underlying disease leading to the surgical or diagnostic procedureCoexisting chronic diseases | |

For the quality control of the interventions, 10% of the recorded interviews will be randomly selected (with the authorisation of the participant, which is stipulated in the informed consent form) for evaluation by an expert using pre-set forms.25 These forms assess the proper performance of the different counselling schemes and the coherence of the interventions with the proposed models. In the event that the evaluation detects a score <4.5/5, retraining will be carried out until the desired score is obtained.

BlindingThe person doing the one-month and three-month follow-up will not otherwise participate in the study and will therefore be blinded to the interventions. The study participants will be blinded to their assignment in the study arms and the person responsible for the analysis will not know the designation of each of the study arms.

Calculation of sample sizeTaking an expected effect of the counselling interventions of 20% compared to a baseline effect (control group) of 10%,28 for an alpha value of 5% and a power of 80% in the study, a sample size of 398 patients was obtained, 199 in each arm. Taking into account the possibility that some patients will drop out of the study or other unanticipated problems, it will be adjusted for a 10% loss. The number of patients in each arm will be 219, for a total of 438 patients to be included in the study at a 1:1 ratio between the two groups, which is close to 440 patients.

The database will be stored in the REDCap software, and the analyses will be carried out in the statistical program STATA version 13 (licence registered by Pontificia Universidad Javeriana).

Expected outcomes and analysis measuresFor the assessment of the primary endpoint, the proportion of people who show progress in their stage of change of the intervened risk factors (analysis within each stratum of smokers, at-risk alcohol consumers, and participants with mixed risk) will be calculated at one month and at three months after the intervention. The difference in proportions of the participants who advanced in their stage of change at these two time points (one and three months) will be calculated using the Z statistical test and the calculation of its significance in both the intervention and control groups. To assess the interaction between the strata, the Breslow-Day and/or Woolf χ2 test will be used, and the assumption of independence will be evaluated (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test). If homogeneity is confirmed, the magnitude and direction of the association can be quantified using the Mantel–Haenszel odds ratio (OR) or risk ratio (RR). In addition, by comparing the Mantel–Haenszel OR against the raw OR, it will be possible to determine whether or not the strata show confounding.

To assess compliance with the secondary endpoint, the proportions of people who have stopped smoking and who adhere to the recommendations for low-risk alcohol consumption (<3 and <4 standard drinks of alcohol per occasion for women and men respectively) will be calculated from hospitalisation to follow-up one and three months after the intervention in both the intervention and control groups. The difference in the above proportions in the two study groups will be established. In addition, the average decrease in the number of cigarettes smoked per month and the average decrease in the AUDIT-C score (short version of the AUDIT questionnaire) at one month and at three months in each of the study arms will be compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

A description of individual and family characteristics in the intervention and control groups will be included. Averages or medians will be used along with their corresponding measures of dispersion for the quantitative variables according to the normality of the distribution; in the case of categorical variables, absolute and relative frequency measures will be used. The Shapiro-Wilk test will be used to evaluate the normality of the variables.

DiscussionChronic diseases continue to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality. The WHO estimates that these diseases are responsible for over 75% of deaths annually.2 Smoking and risky alcohol consumption are modifiable risk factors that contribute to the genesis and early development of complications. A total of 3.3 million people die each year due to alcohol consumption,7 and 6 million due to smoking. 90% of smoking-related deaths occur in people who smoke, and 10% in those exposed to environmental smoke.6 Early identification and brief interventions have long been recommended in primary care settings to prevent and even reduce the harm caused by smoking and alcohol use disorder. There is evidence that these interventions are effective, inexpensive, and cost-effective for both risk factors.10–12,14,17–19,29 However, these studies have predominantly been conducted in outpatient settings, raising questions about their applicability to other contexts such as hospitals. Some studies carried out in hospitalised patients, one in patients with elective surgery, showed that the hospital setting can be conducive to encouraging abstinence from smoking; this is related to an increase in perceived self-efficacy and motivation for perioperative abstinence. Cessation rates are 57–64% at 30 days and 41–44.9% at six months.16–18 Similar results have been found in patients with risky and harmful alcohol consumption in the same situation, where brief interventions could have a positive effect on reducing consumption and limiting the progression of organic and social damage.15

Like similar studies conducted in the outpatient setting, this study will provide novel evidence on the effectiveness of brief counselling interventions in the hospital setting. Moreover, we aim to demonstrate that the screening instruments, behavioural interventions and follow-up strategies used in primary care are also effective in a high complexity hospital. Last of all, this type of intervention can improve patients' attitude towards their own healthcare, by encouraging their desire to have a healthier lifestyle. The results of this study will have a practical application in the implementation of intervention models for risk behaviours in high complexity hospitals.

Ethics and diffusionThe trial was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and Hospital Universitario San Ignacio (approved in 01/2018). The basic ethical principles of this study take into account the security, confidentiality, autonomy and willingness of the study participants. The project's human team took the course on good clinical practices in research and was also trained for the informed consent process (Annex 1). Participating subjects will not be aware of the type of intervention to which they are assigned, to preserve the blinding of the study. The Ethics and Research Committee approved this measure. All subjects would be guaranteed to receive information advising against continuing to smoke or consume alcohol in a risky manner.

FundingThe resources for the preparation of this study were provided by Hospital Universitario de San Ignacio and Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors of this protocol have conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank Dr Maylin Peñaloza for her comments and suggestions on this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Almonacid I, Olaya L, Cuevas V, Sebastián Castillo J, Becerra N, Delgado J, et al. Efectividad de la consejería breve en el ámbito hospitalario para la cesación del tabaquismo y la disminución del consumo riesgoso de alcohol: protocolo de un experimento clínico aleatorizado. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2022;51:146–152.