We describe a case of craving for menthol sweets in a 53-year-old woman with excessive consumption of menthol sweets (100 units/day). She was admitted with a history of rheumatoid arthritis, obesity, anxiety associated with onychophagia and pinching of the skin. Organic disorders were ruled out with paraclinical tests and in-hospital treatment was administered. At discharge, the patient’s condition was stable, but because of exacerbated pain due to the rheumatological disease, she presented depressive symptoms, requiring her medication to be adjusted.

ConclusionsThe “food craving” and anxiety present pathophysiological similarities. Mints have different mechanisms or ways in which they can counteract or control these symptoms, including an increase in serotonin, binding to GABA-A receptors and stimulation of the nicotinic receptor in nerve cells.

Se describe un caso de craving por dulces mentolados, una paciente de 53 años con cuadro de consumo excesivo de dulces mentolados (100 unidades/día). Ingresó con el antecedente de artritis reumatoide, con obesidad, en estado de ansiedad asociado con onicofagia y pellizcos de la piel. Se descartó la organicidad mediante paraclínicos y se le dio asistencia hospitalaria. Al alta, la paciente estaba estable; sin embargo, por progresión del dolor por la enfermedad reumática, ha sufrido síntomas depresivos, por lo que ha requerido ajuste de la medicación.

ConclusionesEl food craving y la ansiedad presentan similitudes fisiopatológicas. Las mentas tienen distintos mecanismos o modos en que pueden contrarrestar o controlar estos síntomas, entre los que está el aumento de serotonina, la unión a receptores GABA-A y la estimulación del receptor nicotínico en las células nerviosas.

Food craving (FC) is the desire to consume a specific foodstuff that is difficult to resist. This condition has been associated with the appearance of obesity and other eating disorders1. It is also associated with mood disturbances, specifically negative emotions, stressful situations, and other events. Among the moods resulting from FC, the most frequent are feelings of guilt, as well as symptoms of anxiety and depression2.

The following is a case of craving for menthol sweets that was treated by the Psychiatry Department of Hospital San Rafael de Tunja (Colombia).

Case reportA 53-year-old single woman came to A&E with symptoms after 1.5 years of excessive intake of menthol sweets. She stated that during the first month she consumed up to 8 mints a day, but she increased her consumption to 50 menthol sweets a day (approximately 2,000 calories/day), and even up to the point where she had 4 to 6 mints in her mouth continuously. In the days before admission, she was consuming up to 100 mints per day.

She reported a family history of anxiety (her father), a personal history of juvenile arthritis and osteoarthritis of the knees treated with abatacept once a month, and a surgical history of gastric bypass seven years earlier, varicosafenectomy and haemorrhoidectomy two years earlier. She stated that he had smoked 15–20 cigarettes a day for 25 years, but had given up five years ago.

In the physical examination upon admission, she showed normal vital signs, with a body mass index of 30.12. She was attentive, notably anxious, logical, coherent, with weakened judgement and uncertain introspection and consideration. Oral health deterioration was evidenced due to halitosis, lacerations to the gums and tongue. Some teeth were broken and there were signs of onychophagia, and multiple self-injury lesions (pathological pinching) were observed on the posterior aspect of the upper limbs and the anterior aspect of the lower limbs, in a state of healing.

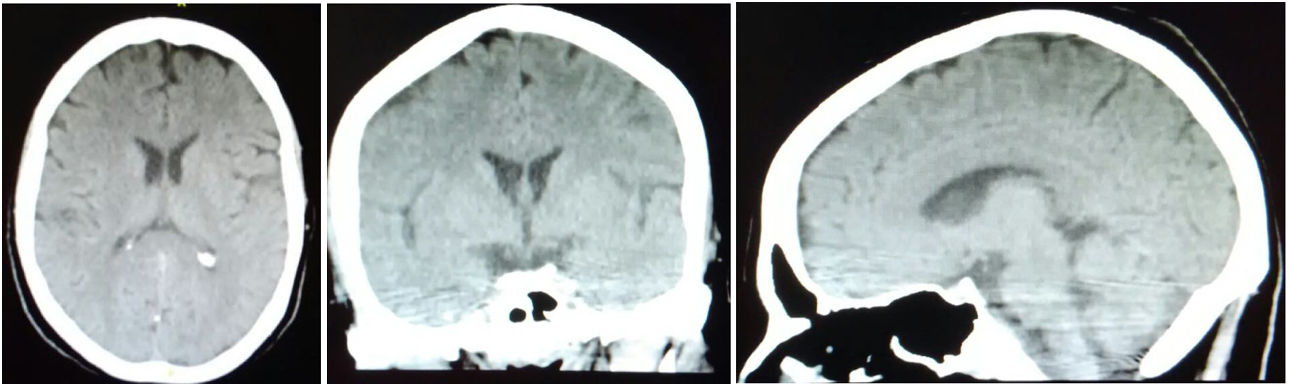

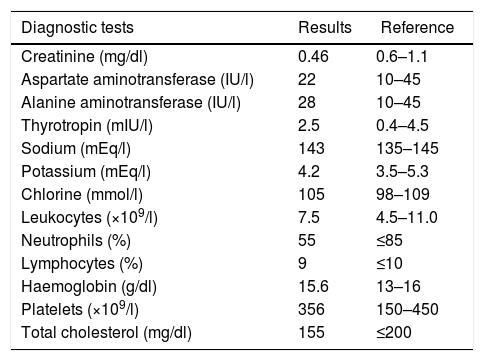

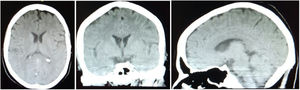

Tests were performed to rule out organicity. A simple computed tomography (CT) scan of the skull did not show structural lesions (Fig. 1). Serum paraclinical studies showed adequate thyroid, kidney and liver functions, fluid and electrolyte balance, and a normal haemogram (Table 1), so any systemic process that could be associated with this condition was ruled out.

Studies on admission.

| Diagnostic tests | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.46 | 0.6–1.1 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/l) | 22 | 10–45 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/l) | 28 | 10–45 |

| Thyrotropin (mIU/l) | 2.5 | 0.4–4.5 |

| Sodium (mEq/l) | 143 | 135–145 |

| Potassium (mEq/l) | 4.2 | 3.5–5.3 |

| Chlorine (mmol/l) | 105 | 98–109 |

| Leukocytes (×109/l) | 7.5 | 4.5–11.0 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 55 | ≤85 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 9 | ≤10 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 15.6 | 13–16 |

| Platelets (×109/l) | 356 | 150–450 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 155 | ≤200 |

The patient was admitted with a diagnosis of unspecified eating disorder (ICD10: F50.9), unspecified anxiety disorder (ICD10: F41.9), and grade I obesity (E66.9). Treatment with fluoxetine 5 ml (20 mg)/day and alprazolam 0.25 mg/8 h was started.

The patient presented noticeable improvement in her anxiety and compulsive symptoms caused by the consumption of menthol sweets, a good sleep pattern during the hospital stay, and a decrease in self-harm attempts. Given her adequate progress and after verifying she was taking the medication properly, it was decided to discharge her one week later, with medication and a follow-up appointment.

On the thirtieth day after discharge, the patient went to the follow-up appointment, reporting a decrease in her consumption of menthol, but a craving for refined sugars, followed by feelings of guilt after ingestion, and a sensation of the unpleasant taste of certain foods. She also had pain in her back and upper limbs and reported that she was only taking fluoxetine and that she did not attend her appointment with a psychologist.

In the third month, she was reassessed, and she stated that she was not taking the medication due to cultural beliefs, “because they damage my kidneys”. Although she had stopped consuming menthol, she was still craving refined sugars. The patient and accompanying family member were explained the need to continue with the medication.

Nine months after discharge, she reported that she suffered permanent pain in her joints due to her rheumatic disease, limiting her ability to walk, associated with general insomnia, anxiety, crying, sadness, irritability, explosiveness and thoughts of death, and a resumption of pathological pinching Therefore, the medical treatment was adjusted to sertraline 50 mg every morning, trazodone 50 mg every night and lorazepam 1 mg every night. The patient remained stable, but 8 months later the benzodiazepine was adjusted, as she was notably anxious and her insomnia had returned. She was adjusted to lorazepam 1 mg (morning and night).

At the time, the patient reported mild symptoms of depression in relation to her pain, without pathological pinching, but again consumption of between 4 to 5 menthol sweets a day, and also onychophagia. The established treatment was continued and she was sent to psychotherapy.

Ethical considerationsBased on resolution 8430 of 1993, which establishes the standards for health research, her informed consent was requested and granted, and the identity of the patient was respected (only sociodemographic and diagnostic data and the treatments administered are reported) when analysing the clinical evolution of the patient.

DiscussionIt has been shown that women have a higher risk of FC, most notably during ovulation or at the beginning of menstruation3. These differences in eating behaviour according to gender are due to the neuronal organisation during the prenatal stage dependent on hormonal stimuli, in which oestrogens are the most decisive4.

Anatomically, it is known that FC is related to the functioning of the reward system, which has structures such as the hippocampus, the amygdala, the nucleus accumbens and the prefrontal cortex, among others. These structures are also affected in anxiety disorders5, and this explains the comorbidity in the case presented.

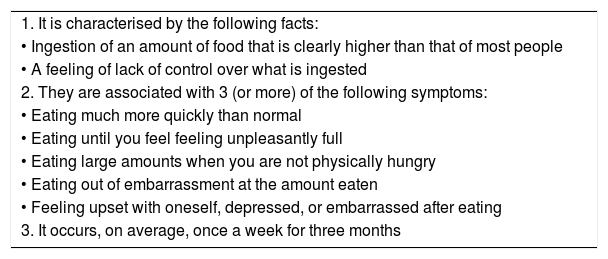

The differential diagnosis between FC and anxiety disorders can be supported by the Yale scale for food addiction. Its version in Spanish is validated in a Mexican population, has adequate psychometric properties and allows us to identify cases of craving6. Furthermore, the diagnosis can be supported by the criteria established in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (Table 2)7.

DSM–5 diagnostic criteria7.

| 1. It is characterised by the following facts: |

| • Ingestion of an amount of food that is clearly higher than that of most people |

| • A feeling of lack of control over what is ingested |

| 2. They are associated with 3 (or more) of the following symptoms: |

| • Eating much more quickly than normal |

| • Eating until you feel feeling unpleasantly full |

| • Eating large amounts when you are not physically hungry |

| • Eating out of embarrassment at the amount eaten |

| • Feeling upset with oneself, depressed, or embarrassed after eating |

| 3. It occurs, on average, once a week for three months |

The pathophysiology shows that the neuronal activity of the serotonin pathways is increased in the craving due to the increase in plasma cortisol. This increase aims to regulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. However, if this response is maintained chronically, it leads to a decrease in tryptophan that leads the patient to a high carbohydrate intake, the aim of which is to restore the concentration of serotonin8,9.

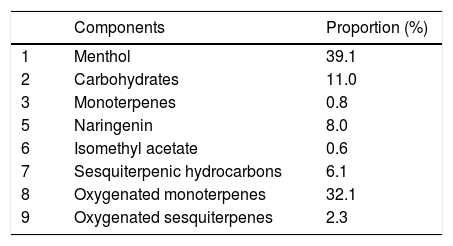

Regarding the craving for menthol, the hypothesis proposed is that large amounts of carbohydrates are found in the composition of these sweets (Table 3)10. Other studies have shown that menthol sweets contain some substances such as naringenin, which acts in a similar way to benzodiazepines by binding to the GABA-A receptor, and possibly has an anxiolytic effect, in addition to an inhibitory activity of monoamine oxidase (MAOI) that increases serotonin concentration11,12. These effects could explain the patient's behaviour with menthol sweets.

Composition of mints.

| Components | Proportion (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Menthol | 39.1 |

| 2 | Carbohydrates | 11.0 |

| 3 | Monoterpenes | 0.8 |

| 5 | Naringenin | 8.0 |

| 6 | Isomethyl acetate | 0.6 |

| 7 | Sesquiterpenic hydrocarbons | 6.1 |

| 8 | Oxygenated monoterpenes | 32.1 |

| 9 | Oxygenated sesquiterpenes | 2.3 |

Taken and adapted from Isidora et al.10.

Another peculiarity of menthol is that it binds to a type of nicotinic receptor within nerve cells and promotes the expression of other genes in the reward and pleasure regions, a stimulus similar to that produced with tobacco consumption13, which could explain the need to increase the number of mints consumed by the patient to obtain a pleasurable response.

It has been found that there is a significant relationship between glucose compulsion and altered anthropometric profile, for which these patients present some degree of overweight or obesity14. However, recent discoveries have shown that the most powerful brain circuit to control food consumption also regulates lipid metabolism15.

Some studies have shown that aromatherapy with substances such as peppermint leads to responses such as greater relaxation, increased motivation and vigour, and more locomotor activity16.

It can be said that anxiety and eating disorders seem to share a number of common characteristics. Proof of this would be the phenomenological similarities, characteristics (age of onset, course and comorbidity), aetiology, risk factors and response to pharmacological and/or behavioural treatments, demonstrated by a recent meta-analysis, which indicates that there is a positive correlation between these two conditions17. The natural progression of these untreated conditions tends to be chronic and to have an unfavourable prognosis18.

In conclusion, it is common to find an association between anxiety disorder and eating behaviour disorders, which have a pathophysiological correlation, but a behaviour as specific as in this case towards the consumption of menthol sweets is very rare.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Muñoz OH, Maldonado JCA, Rodríguez LJV, Sanabria MBA. Craving por mentolados: a propósito de un caso. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:301–304.

The expression food craving can be perfectly and exactly translated by the Spanish terms “antojo” or “craving for foodstuff”.