There are very few studies on the consumption of psychoactive substances (PAS) among young people from indigenous territories and evening or blended learning students. In Inírida, a municipality in the Colombian Amazon, there were concerns about a possible consumption issue that had never been characterised before.

ObjectiveTo characterise the consumption of alcohol, tobacco and PAS in Inírida among teenage evening and blended learning students.

MethodsThe Inter-American Uniform Drug Use Data System (SIDUC) survey developed by the Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (CICAD) was adapted to the cultural context and carried out on 95% of 284 evening and blended learning students (262). Descriptive statistics and multiple correspondence analyses were used.

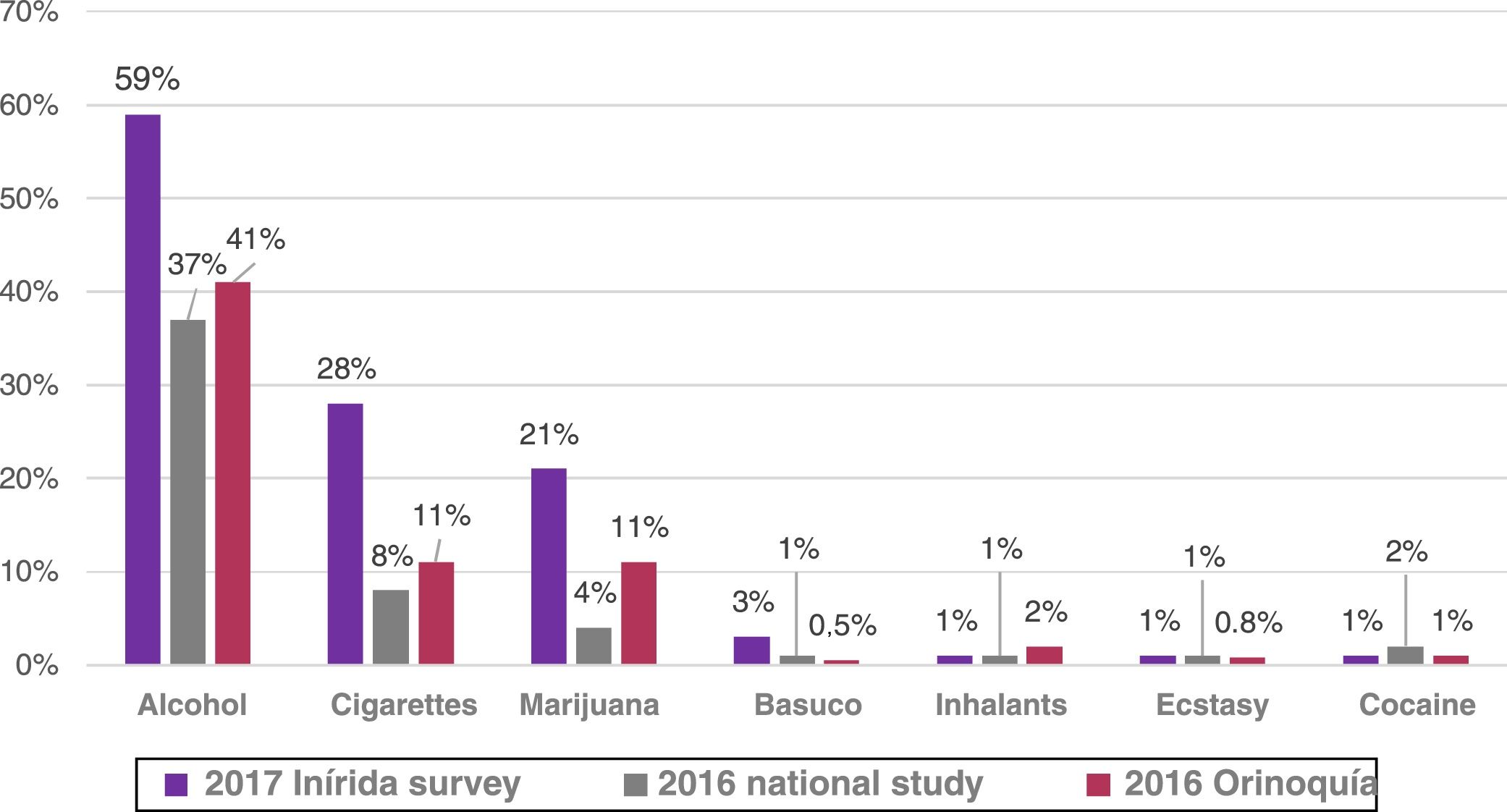

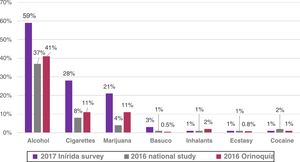

ResultsCurrently, 59% consume alcohol; 28% tobacco; 21% marijuana; 3% cocaine paste; 1% ecstasy (MDMA); 1% cocaine; and 1% inhalants. Also, 61% believe that drugs are available inside and around the vicinity of their school, and that marijuana (62%) and cocaine paste (35%) are easily acquired. Drugs are most commonly offered in neighbourhoods (56%) and at parties (30%). Those offering the highest quantity of drugs are acquaintances (35%) and friends (29%). And 51% stated that they had participated in preventive activities related to consumption.

ConclusionsCurrently, the population has a higher consumption of the substances studied in comparison with the national reference, that of Orinoquía and Amazonía, with the exception of cocaine and inhalants. The consumption situation was confirmed, so participatory actions are proposed.

Existen muy pocos estudios sobre el consumo de sustancias psicoactivas (SPA) en jóvenes de territorios indígenas y en estudiantes semipresenciales o nocturnos. En Inírida, municipio de la Amazonía colombiana, preocupaba un posible problema de consumo nunca caracterizado.

ObjetivoCaracterizar el consumo de alcohol, tabaco y SPA en adolescentes de Inírida escolarizados en jornada nocturna y semipresencial.

MétodosEncuesta CICAD/SIDUC, ajustada al contexto cultural, al 95% de los 284 estudiantes de la jornada elegida (n = 262). Se utilizó estadística descriptiva y análisis de correspondencias múltiples.

ResultadosActualmente consume alcohol el 59%; cigarrillo, el 28%; marihuana, el 21%; basuco, el 3%; éxtasis, el 1%; cocaína, el 1%, e inhalables, el 1%. El 61% considera que en el colegio y alrededores hay disponibilidad de drogas y es fácil conseguir marihuana (62%) y basuco (35%). Se ofrecen drogas con mayor frecuencia en el barrio (56%) y las fiestas (30%). Las personas que más les ofrecen drogas son conocidos (35%) y amigos (29%). El 51% manifiesta haber recibido actividades de prevención del consumo.

ConclusionesLa población actualmente hace mayor consumo de las sustancias estudiadas que el referente nacional y de la Orinoquía y Amazonía y Amazonía, excepto en cocaína e inhalables. Se corrobora la situación de consumo y se proponen acciones participativas.

Guainía is a multi-ethnic and multi-border Colombian department in the Amazon region that has undergone accelerated processes of westernisation since the mid-twentieth century. It has an 83% indigenous population, mostly belonging to the Puinave, Curripaco, Sikuani and Piapoco ethnic groups.1

Inírida is the only municipality and capital of Guainía. In 2017, it had 20,100 inhabitants, 60.3% of them indigenous, with a predominance of young people.2 It receives migrants due forced internal displacement as well as migrants from Venezuela. Its high levels of unemployment and unmet basic needs3 force heads of households to dedicate most of their time to informal and low-paying jobs away from home, or to be out of town for long periods to work in the gold mines, mainly those of Yacapana in Venezuela, leaving their children in the care of third parties or without adult accompaniment. In 2016, healthcare personnel identified a previously unreported problem of use of psychoactive substances (PASs) in young people. An increase in PAS dealers was also detected, in addition to the absence of strong public policies aimed at controlling micro-trafficking. Around the municipality's schools, PASs are offered at minimal prices (0.3 dollars per dose in 2018).

Alcohol, tobacco and PAS consumption patterns are multidimensional in nature, and the difficult conditions faced by the world's indigenous adolescents, such as poverty, marginalisation and low presence of the State, make them a vulnerable group for the development of problematic use.4–7

In Colombia there is a national study on PAS use in schoolchildren, with data from the Orinoco and Amazon regions; the study sample has not included young people from Guainía.8 In order to have a clear diagnosis of the situation of use at the municipal level that would allow for effective interventions, this study sought to identify the frequencies of alcohol, cigarette and PAS consumption; to characterise the school, family, social and economic conditions that the literature has described as related to such consumption; and to characterise access, perception of risk, exposure to risks and participation in prevention or treatment programmes in adolescents enrolled in blended and night school in Inírida.

MethodsDescriptive, cross-sectional, self-administered, anonymous, survey-based study. The Comisión Interamericana para el control del Abuso de Drogas [Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission] Sistema Interamericano de Datos Uniformes sobre consumo de Drogas [Inter-American Drug Use Data System] (CICAD/SIDUC),9 which has been used in secondary school students in the region, was used. The cultural adaptation recommended by the CICAD/SIDUC was made and, on the recommendation of the ethics committee, some questions were deleted so as not to overwhelm students whose native language is not necessarily Spanish and to avoid indirectly promoting other PASs. In the case of tobacco, only cigarette consumption was investigated.

The adjusted survey was conducted without the presence of teachers and confidentiality was ensured. Of the 284 students (100%) enrolled in a school with blended and evening courses in Inírida, 262 students (95%) who were in school on the study dates (late 2017), with an age range of 10−19 years, were surveyed. Blended and evening courses were chosen because the municipal government planned to survey daytime schools. Exclusion criteria: people who did not want to participate in the study and people who were not in a mental or physical condition to self-administer the survey.

Consumption was understood as the use of licit and illicit substances, one or more times, in a specific period. Consumption in the last month or current consumption: use of a certain substance one or more times in the last 30 days. Consumption in the last year or recent consumption: one or more times in the last 12 months. Consumption at some point in life: one or more times in any period of one's life.10

Quantitative variables were summarised using measures of central tendency and dispersion, and qualitative variables were summarised using absolute and relative frequencies. A multiple correspondence analysis was performed to characterise consumption. The statistical analysis of the information was performed in Stata 13 and SPAD 7.3.

The study was approved by the departmental Education Secretariat, the administration of the educational institution, the parents' association, and an Ethics Committee which deemed it of minimal risk.

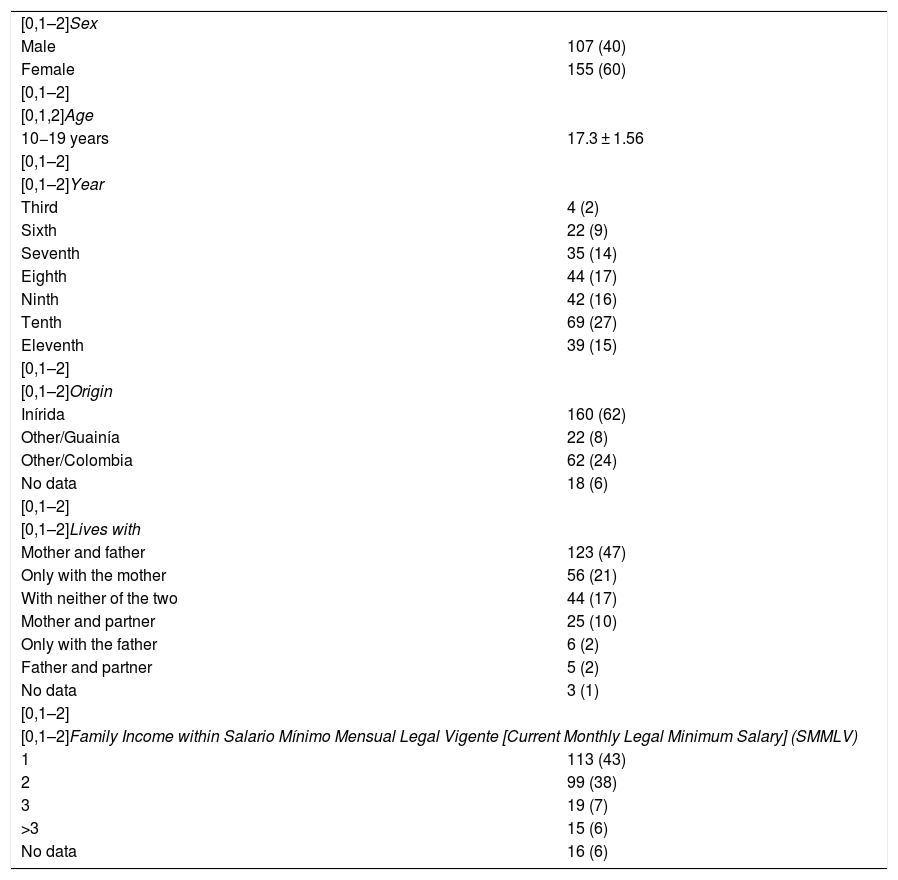

ResultsOf the 262 participants, 60% were female. The average age was 17.3 ± 1.56 years; 62% were natives of Inírida, 35% were mestizo or colonist, 23% were Puinave, 16% were Curripaco and the remaining 26% were distributed among the Sicuani, Piapoco, Cubeo and Yeral ethnic groups. Most were in the tenth grade (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the students.

| [0,1–2]Sex | |

| Male | 107 (40) |

| Female | 155 (60) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1,2]Age | |

| 10−19 years | 17.3 ± 1.56 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Year | |

| Third | 4 (2) |

| Sixth | 22 (9) |

| Seventh | 35 (14) |

| Eighth | 44 (17) |

| Ninth | 42 (16) |

| Tenth | 69 (27) |

| Eleventh | 39 (15) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Origin | |

| Inírida | 160 (62) |

| Other/Guainía | 22 (8) |

| Other/Colombia | 62 (24) |

| No data | 18 (6) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Lives with | |

| Mother and father | 123 (47) |

| Only with the mother | 56 (21) |

| With neither of the two | 44 (17) |

| Mother and partner | 25 (10) |

| Only with the father | 6 (2) |

| Father and partner | 5 (2) |

| No data | 3 (1) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Family Income within Salario Mínimo Mensual Legal Vigente [Current Monthly Legal Minimum Salary] (SMMLV) | |

| 1 | 113 (43) |

| 2 | 99 (38) |

| 3 | 19 (7) |

| >3 | 15 (6) |

| No data | 16 (6) |

Values are expressed in terms of n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

Current cigarette consumption was 28% and consumption at some point in life was 55% (males 30% and females 25%). The average age of first use was 14 years. The majority of those who have smoked cigarettes at some point in life were in the tenth grade (30%), followed by the eighth grade (19%). The highest consumption was recorded at 18 years (39%).

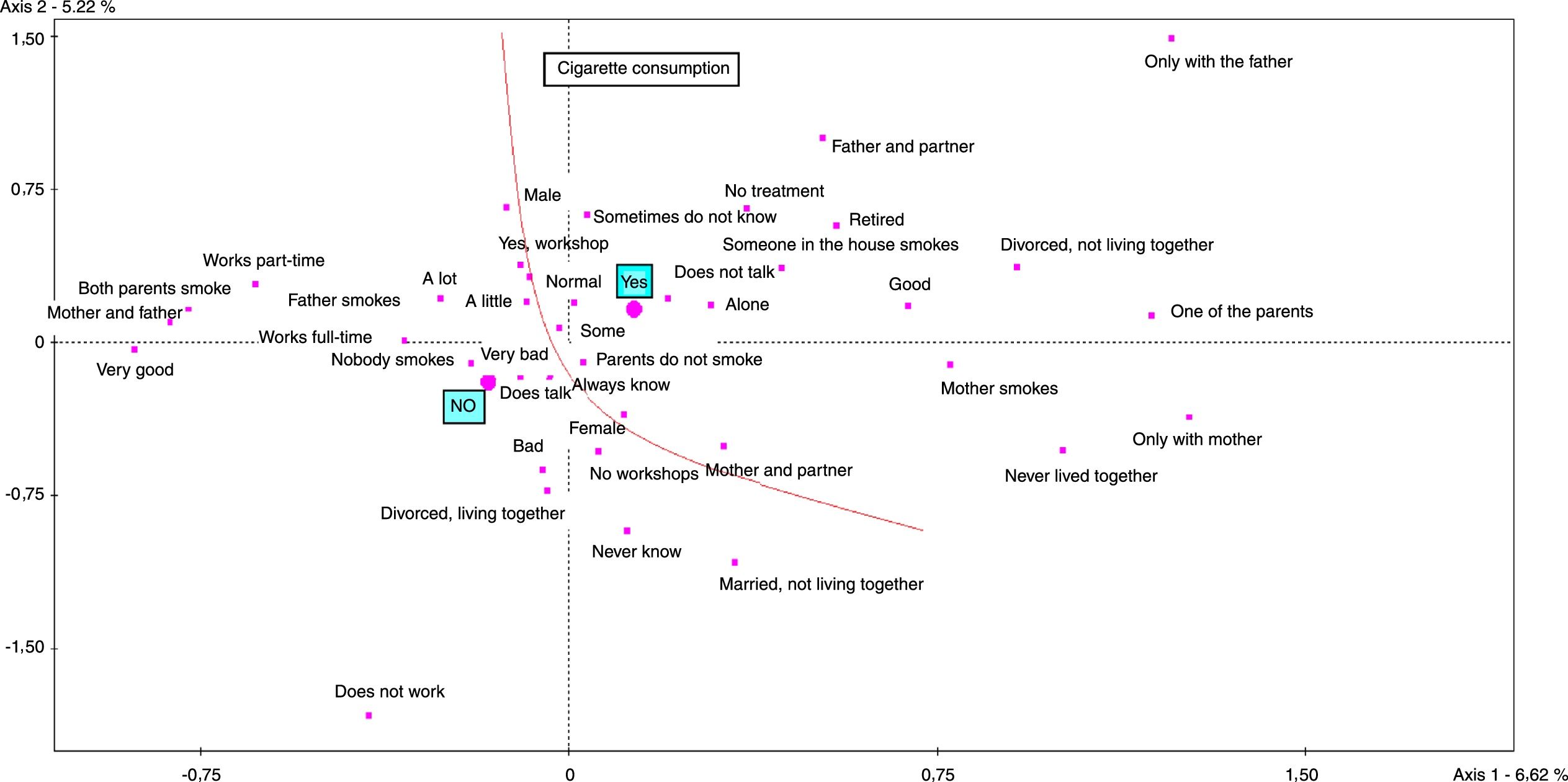

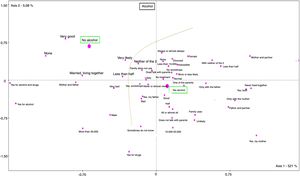

Among those who currently smoke cigarettes, certain characteristics were found, such as having a smoker in the home, not having talked with parents about the danger of using drugs, having participated in consumption prevention activities but not finding them to their liking, having a normal or fair financial situation and having parents who do not smoke (Fig. 1).

Alcohol use68% of the students have consumed alcohol in the last 12 months, 59% have done so in the last 30 days and 85% have done so at some point in life. There is a slight female majority (58% compared to 42%). 43% said they had not consumed alcoholic beverages in the last 2 weeks.

By year, 28% were in the tenth grade, 19% were in the eighth grade, 17% were in the eleventh grade and 16% were in the ninth grade. The group that started consuming alcohol at 13–16 years of age comprised 51%, followed by the groups who started at 10-12 (21%), 17-20 (13%) and under 10 years of age (1%).

The most frequently consumed liquor was beer (33%) on weekends, followed by hard liquors (29%): whiskey, vodka, brandy and rum.

19% stated that all or almost all of their friends consume alcohol on weekends, and 18% reported that half of their friends do. 32% reported that their father consumes alcohol, 11% reported that both their parents do and 4% reported that their mother does.

Of the students who currently consume alcohol, 14% have family problems, 11.5% perform poorly on tests and 4.72% have problems with the police.

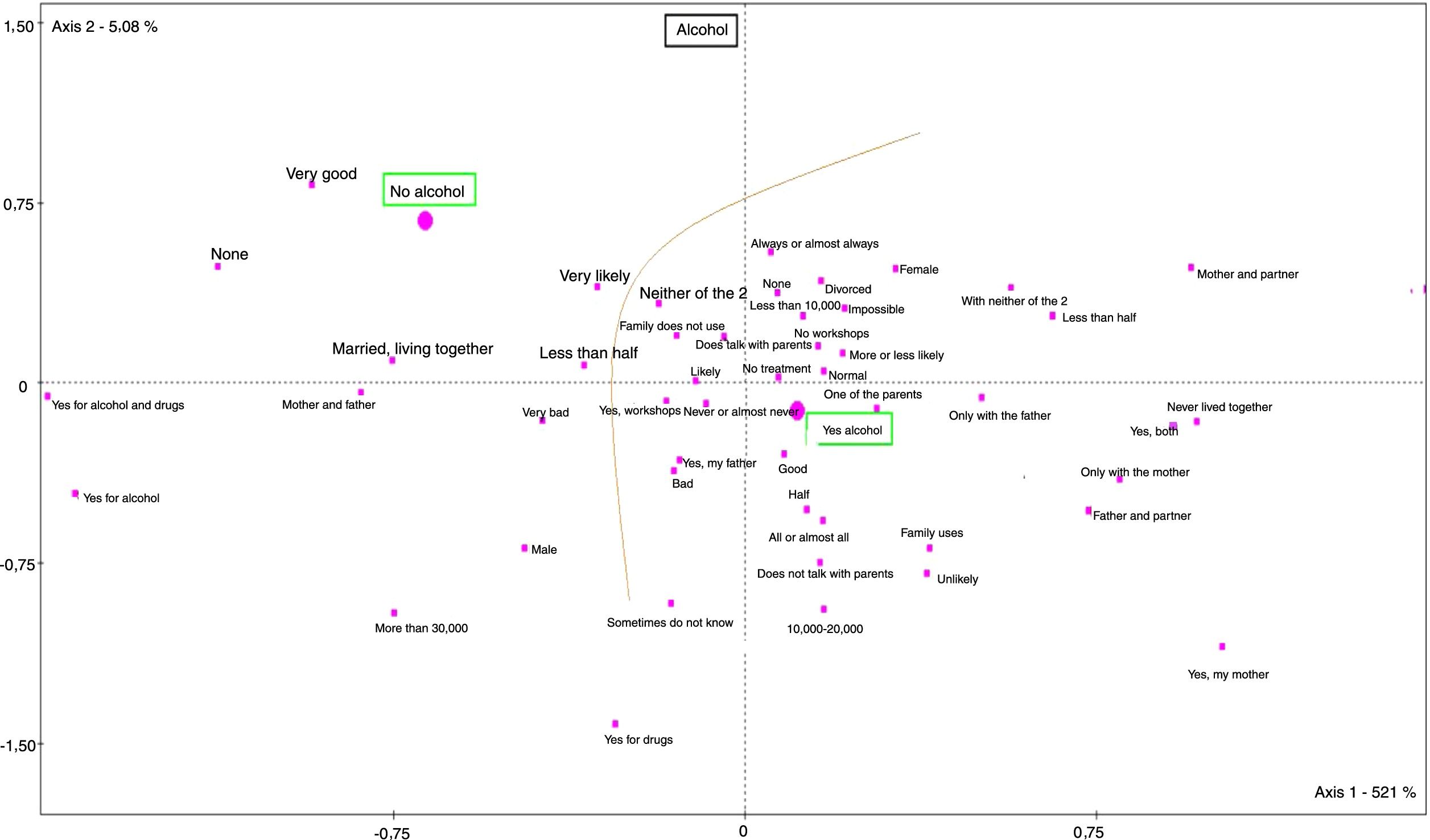

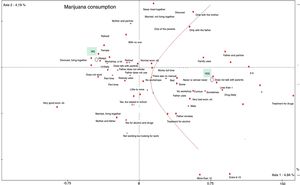

Current consumption of alcohol was more common in women than in men, the parents never or almost never know where they are, they have not spoken with their parents about the danger of using drugs, some of the parents also consume alcoholic beverages, they live with only one of their parents, they have a family member who uses some type of substance, almost all or at least half of their friends consume alcohol on weekends, they perceive their economic situation as good, they have received neither workshops to prevent consumption nor treatment, and they considered their own admission to university unlikely (Fig. 2).

Marijuana consumptionMarijuana consumption in the last 12 months was found in 16%, current consumption was found in 21% and consumption at some point in life was found in 37% (22% men and 15% women). Among those having used marijuana at some point in life, 21% were in the eighth grade, 16% were in the seventh grade and 15% were in the tenth grade.

Among those who use marijuana weekly or daily, 17% have family problems, 52% perform poorly on tests and 12% have problems with the police. 19% of respondents say that less than half their friends use marijuana and 9% say that half their friends do so.

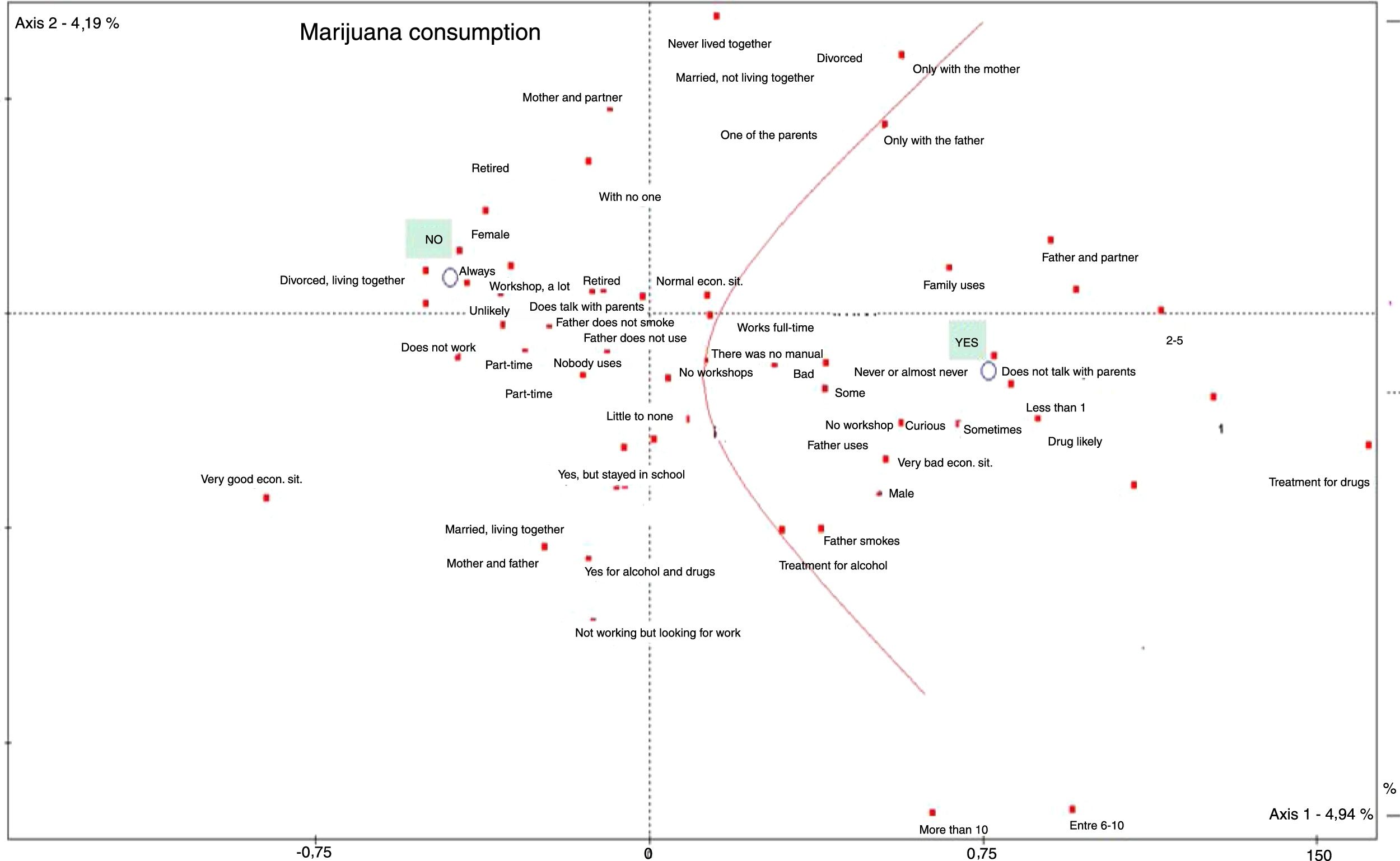

Among those who report current marijuana use, certain characteristics were found, such as: the majority are male; the parents never or almost never know where they are; they do not talk to their parents about the danger of using substances; someone in the family uses substances; the parents work all day; they consider their economic situation to be bad; most say they have received neither workshops, manuals, or materials for preventing consumption nor treatment; and they use 1-5 marijuana joints each time they go out with friends (Fig. 3).

Basuco consumptionThe use of basuco, or coca paste, was found in 6% (3% women and 2.6% men) at some point in life; 5% in the last 12 months and 3% in the last 30 days. Among those who have used it at some point in life, 20% are in the eighth grade; 15% are in the ninth grade and 10% are in the seventh grade.

Use of inhalants4% stated that they had used inhalants at some point in their lives (2.57% women and 1.42% men); 1% had used them in the last 12 months and 1% had used them in the last 30 days. Those who had used them were in eighth grade (20%), ninth grade (20%) or tenth grade (20%); there was no evidence of use in sixth grade or eleventh grade.

Ecstasy consumption3% of the students reported having used ecstasy at some point in their lives (males 2% and females 1%); 1% reported having done so in the last 12 months and 1% reported having done so in the last 30 days.

By year, those who used at some point their life are in the eighth grade (35%), seventh grade (25%) or tenth grade (25%).

Cocaine consumption2.36% of the students reported having used cocaine at some point in their lives (males 1.5% and females 0.86%); 1% reported having done so in the last 12 months and another 1% reported having done so in the last 30 days.

Polydrug use31% of the adolescents use more than one substance at the same time. The most common combination is alcohol plus cigarettes (17%), followed by alcohol plus marijuana and cigarettes (5%), and alcohol plus marijuana (2%). Almost all cigarette users use at least one other substance. Of the remaining 69%, 33% do not use any substances, 31% use only alcohol, 4% use only cigarettes and 1% use only marijuana. 2.3% have received treatment at some point in their life for alcohol, 1% have for drugs and another 1% have for alcohol and drugs.

Other conditions of consumption80% of those surveyed talk to their parents about the danger of using drugs and 19% have a sibling or other person at home who uses drugs.

61% are aware of the presence of PASs in the school and its surroundings, 50% have witnessed use in or around the school, 37% have witnessed the sale of PASs in or around the school and 50% have seen a student using drugs in or around the school. The easiest substances to obtain are marijuana (62%), basuco (35%), cocaine (15%) and ecstasy (9%). Although some substances are hard to come by, all are being offered to students.

The place where marijuana was offered the most was in the neighbourhood (56%) and at parties (30%). Marijuana is offered by acquaintances (35%) or friends (29%); cocaine is offered by strangers (25%) or acquaintances (14%); basuco is offered by strangers (18%) or friends (15%); ecstasy is offered by strangers (19%) or acquaintances (7%).

The respondents report that, due to the consumption of alcohol or illicit substances, 19% have had family problems, 10%, have performed poorly on a test, 4% have had problems with the police and 4% have been in a big fight. 51% report having participated in drug prevention activities at school this year.

DiscussionThe results obtained correspond to blended and evening students, so they cannot be fully extrapolated to the daytime population or to the municipal, departmental or national population. However, the results are useful for local authorities as they confirm that PAS consumption exists and requires intervention.

The findings will be balanced against the 2018 national study, as it is the most similar, includes data for the Orinoquía and Amazon regions (OA) and uses the same survey instrument. For both licit and illicit substances, the current, annual and "at some point in life" consumption rates in this study are higher than those in the national study, both in general and in the OA,8 as described below (Fig. 4).

The highest recorded consumption is that of alcohol, according to both national and OA data, followed by cigarette consumption, which in this study is more than double that in the OA despite multiple national efforts to control tobacco, with public policies aimed at reducing its consumption, such as the increase in the tobacco tax, massive advertising campaigns, smoke-free closed environments and restrictions on advertising.11 Taking into account the legal nature of both substances, one could wonder if it is necessary to re-evaluate existing measures or look for alternative strategies to discourage demand and consumption while simultaneously pursuing others to effectively reduce supply.

It is also worth considering whether there is customary endorsement of the use of these substances in the family context, in the educational community and in the general population of Inírida, which may be promoting the availability of and interest in the substances despite efforts made to control them. When consumption of a substance is habitual and widely socially accepted in a given context, there is a great possibility that this social norm will overlap the juridical/legal norm, which may promote a change in the perception of the substance and the risk that it entails and therefore influence motivations for consumption.12

With regard to marijuana, the consumption rate found in this study (21%) is much higher than those in the national study, in the country (4%) and in the OA (11.3%). However, it is not far from that seen in other (daytime) school contexts in which the consumption of this substance is predominant. It is striking that it is above the national figures, but the factors that may affect the dissemination thereof require further investigation.

Rates of consumption of basuco at some point in life, consumption in the last 12 months and current consumption are more than double the national and OA figures. It is important to start a discussion about this substance (coca paste), regardless of the values obtained, as it is linked to greater cognitive and social deterioration and as it carries a greater stigma.13–15

The use of inhalants at some point in life and in the last 12 months was lower than that of the national study, and current consumption was similar.

The rate of consumption of ecstasy at some point in life was higher than the national rate, while rates of consumption in the last 12 months and current consumption were similar to national and OA values. In both studies, consumption of ecstasy was higher among males than females.

With regard to cocaine consumption, the same values were found as in the OA, while rates of consumption at some point in life, consumption in the last 12 months and current consumption were lower compared to the national values, with higher consumption in men than in women, in both cases.

Most of the students, both this study and in the national study, are aware of the presence and sale of PASs in and around the school, as well as consumption by students. In both studies, the easiest substance to obtain is marijuana, followed by basuco; the most difficult to access is ecstasy.

Regarding other illegal substances, the diversity of substances found is striking. Taking into account the level of inhalant use found, the lack of discrimination by type of inhalant and the fact that certain substances were removed from the instrument in the process of cultural and ethical adaptation, the possibility that a market for substances is still expanding undetected in Inírida or Guainía cannot be ruled out. Dialogues on this subject must be initiated between community actors and state institutions in order to specifically investigate inhalants such as glue, poppers, dicks (isopropyl nitrite), ladies (methylene chloride) and many others that are increasing in the country.16

The same could be said about the possible use of other synthetic drugs, in addition to ecstasy; notably, the use of ecstasy, a drug traditionally recognised as urban or metropolitan, has been found among these adolescents.

This situation is also a call for future studies to take into account the disadvantages of lumping together different types of consumption when creating specific and effective intervention strategies.

Other studies in Latin America have characterised the consumption of alcohol and psychoactive substances in indigenous and non-indigenous adolescents, such as a 2015 study on patterns of PAS consumption in the indigenous population residing in and originally from Mexico City,17 wherein the highest alcohol rates of consumption corresponded to alcohol (47.4% of males and 49.4% of females), followed by tobacco (22.9% of both females and males) and marijuana (17.1% of males and 13.1% of females), with lower results than our own. There was evidence of higher rates of use of inhalants: 11.1% of males and 13.1% of females.

Another study conducted in 450 indigenous and mestizo high school students from the Saraguro canton in Loja, Ecuador,18 also found that the most commonly consumed substances, both by indigenous and mestizo students, were alcohol (62.3% of males and 41.4% of females), followed by marijuana (17.1% of males and 4.9% of females) and other inhalants, coca paste, cocaine, heroin and ecstasy (with percentages <1%).

No comparison was made to other Colombian studies in young people, due to differences in the population or in the instrument used.19,20

This contribution would be incomplete if Guainian society were not offered at least an outline of possible interventions based on the current evidence; the remainder of this section offers such an outline.

In the case of interventions in PAS consumption with minors, methodologies must be designed in which the contextual aspects of consumption are the centre of attention, rather than the substances themselves. It is even proposed that mentions of PASs be minimal or almost null, without ignoring their existence in certain cases or obscuring reality in a way that may be unfavourable for intervention.

The starting point should be with a conception of substance use that steps away from notions of social dysfunction (the user as a deviant from social norms) and physical disease (substance use as a merely toxicological matter linked to addiction). Large parts of the literature and existing policies have revolved around these notions. Extensive reassessment of these approaches in various interdisciplinary scientific studies has found that not only are they ineffective, they do more harm than good.21–25 Substance use should be understood as a product of decision-making by an individual at a certain time and in a certain place arising from the confluence of various factors (cultural, historical, sociodemographic, political, environmental, psychological, biological, etc.) in that individual's life. This calls for a complex reading in which simplistic ideas about right and wrong are avoided and polarising attitudes that fail to appreciate the shades of grey that account for the appearance and course of the phenomenon are abandoned.

In addition, due to the characteristics of Inírida and Guainía, the design of prevention strategies should take into account the characteristics of their ethnic groups (cosmogony, outlook on PAS consumption, approaches pursued in communities, etc.) and the approach taken should entail differentiated actions for each population, age and community group.

The premises of community participation and social construction must also be taken into account. These are understood as the involvement of the different social factors that are key in the design, implementation and evaluation of a comprehensive strategy for preventing and addressing consumption in the development of key consensuses so that this strategy works in a comprehensive, cross-cutting fashion.

For this reason, indigenous and community leaders, various state entities (education, health, recreation, culture, police and other sectors), and the general population must be included. In the case of the school community, there must be highly active participation by students, teachers and parents. The starting point for strategies for teachers and parents, unlike those for students, should be information about PASs, their consumption and the implications thereof, with a view to broadening knowledge and eliminating misconceptions that may be harmful or lead to poor practices in addressing and approaching these matters with counterproductive effects on students.

Thus, adhering to the characteristics of internationally recognised interventions for the development of good practices and according to the indications of national studies, the strategy or set of strategies pursued should, in short, be centred on these particular characteristics26:

- 1

They should be based in secondary school. They should not exclude capacity-building activities for boys and girls in primary school or early childhood.

- 2

They should be targeted with an emphasis on the population of the grades in which PAS consumption begins.

- 3

They should include activities with parents or responsible adults (at home).

- 4

They should use a broad framework for strengthening life skills, rather than a restrictive framework focused solely on the issue of drugs.

- 5

They should be pursued with a dynamic and participatory schedule of activities.

- 6

They should involve activities among peers.

- 7

They should consider the community environment.

- 8

They should involve teachers, taking into account the differential considerations mentioned above.

- 9

They should include the use of communication technologies (if the material conditions of the context and the community allow it).

- 10

They should have a defined evaluation process.

It is also necessary to map out the municipality's different existing prevention strategies and to evaluate, in light of these criteria, whether they meet expectations. Likewise, the community in general must evaluate the effectiveness and relevance of these strategies.

The strategies should have the ultimate goal of strengthening the following matters, identified as key to producing autonomous individuals able to manage risk and make important life decisions:

- •

Bolstering of life skills. Activities that help to build up individuals with skills for managing success, and, at the same time, resilience for coping with life's inevitable difficulties, having their own resources so that they are not subjected to certain situations. This also includes strengthening of critical thinking and knowledge of citizens' rights and duties, among many other similar activities.

- •

Sociocultural and recreational alternatives. These include all kinds of activities that strengthen students' creative and expressive capacities, taking into account their diversity of intelligences and interests. Students learn to suitably manage their free time and are able to take advantage of stimulating cultural, recreational and sports activities for personal development.

- •

Mobilisation of social networks. These seek to stimulate sociability and strengthen students' social ties in family, community and peer settings, promoting communication and empathy as guidelines.

- •

Community work. Activities that strengthen the notion of community and the rebuilding of social fabric, enabling students to understand the importance of community work and individual participation and capacity in various situations. Promotion of individuality and the pursuit of success based on goals rather than processes (as is the case with grading in schools) have been found to be factors that generate stress and anguish, which may then serve as motivators for PAS consumption.

- •

Availability of comprehensive and differential care. Apart from the availability of services and strategies to address the above-mentioned matters, spaces should be created that promote the reporting of potentially problematic situations that may or may not motivate PAS consumption. It is proposed that experiences around listening centres or areas, psychological support processes and the like be reviewed.

- •

In addition, for students who engage in problematic substance use and voluntarily request support in quitting or intervention in a specific aspect of their life that motivates such use, there should be comprehensive treatment services and a review of those students' particular life context, to ensure the effectiveness of the treatment and avoid relapses in problematic use.

In the surveyed population, the rate of current consumption of the substances studied is higher than the national rate, except for cocaine, which is lower, and inhalants, which is similar. Similar studies must be conducted in daytime students, but this study corroborates the existence of a situation of use that warrants action. To the extent possible, this action should be participatory, cross-cutting and aligned with the local culture.

FundingThis research was funded by an internal call for bids by the FUCS (163-8417-8) and by Colciencias (CT 748-2016).

Conflicts of interestNone.

To the directors, students and parents' association of the educational institution and the Inírida Municipal Education Secretariat.

Please cite this article as: Pedroza-Buitrago A, Pulido-Reynel A, Ardila-Sierra A, Villa-Roel SM, González P, Niño L, et al. Consumo de alcohol, tabaco y sustancias psicoactivas en adolescentes de un territorio indígena en la Amazonía colombiana. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:246–254.

Undergraduate thesis: This study corresponds to the undergraduate thesis entitled "Consumption of alcohol, tobacco, psychoactive substances in adolescents enrolled in a school with blended, evening courses in Inírida, Guainía", for the Specialisation in Family Medicine by the authors, Pedroza-Buitrago, Pulido-Reynel. Approved in 2018, by the Fundación la Universitaria de Ciencias de la Salud [Health Sciences University Foundation] (FUCS).

This work was presented as a poster at the XXVII Jornada de Investigación Posgrado de Medicina [27th Conference on Postgraduate Research in Medicine], held in Bogotá, DC, on 25 January 2019. The title of the poster was "Consumption of alcohol, tobacco and psychoactive substances in adolescents enrolled in a school with blended and evening courses in Inírida, Guainía".