Although the absence of memory impairment was considered among the diagnostic criteria to differentiate Alzheimer’s disease (AD) from Behavioural Variant of Frontotemporal Dementia (bvFTD), current and growing evidence indicates that a significant percentage of cases of bvFTD present with episodic memory deficits. In order to compare the performance profile of the naming capacity and episodic memory in patients with AD and bvFTD the present study was designed.

MethodsCross-sectional and analytical study with control group (32 people). The study included 42 people with probable AD and 22 with probable bvFTD, all over 60 years old. Uniform Data Set instruments validated in Spanish were used: Multilingual Naming Test (MINT), Craft-21 history and Benson’s complex figure, among others.

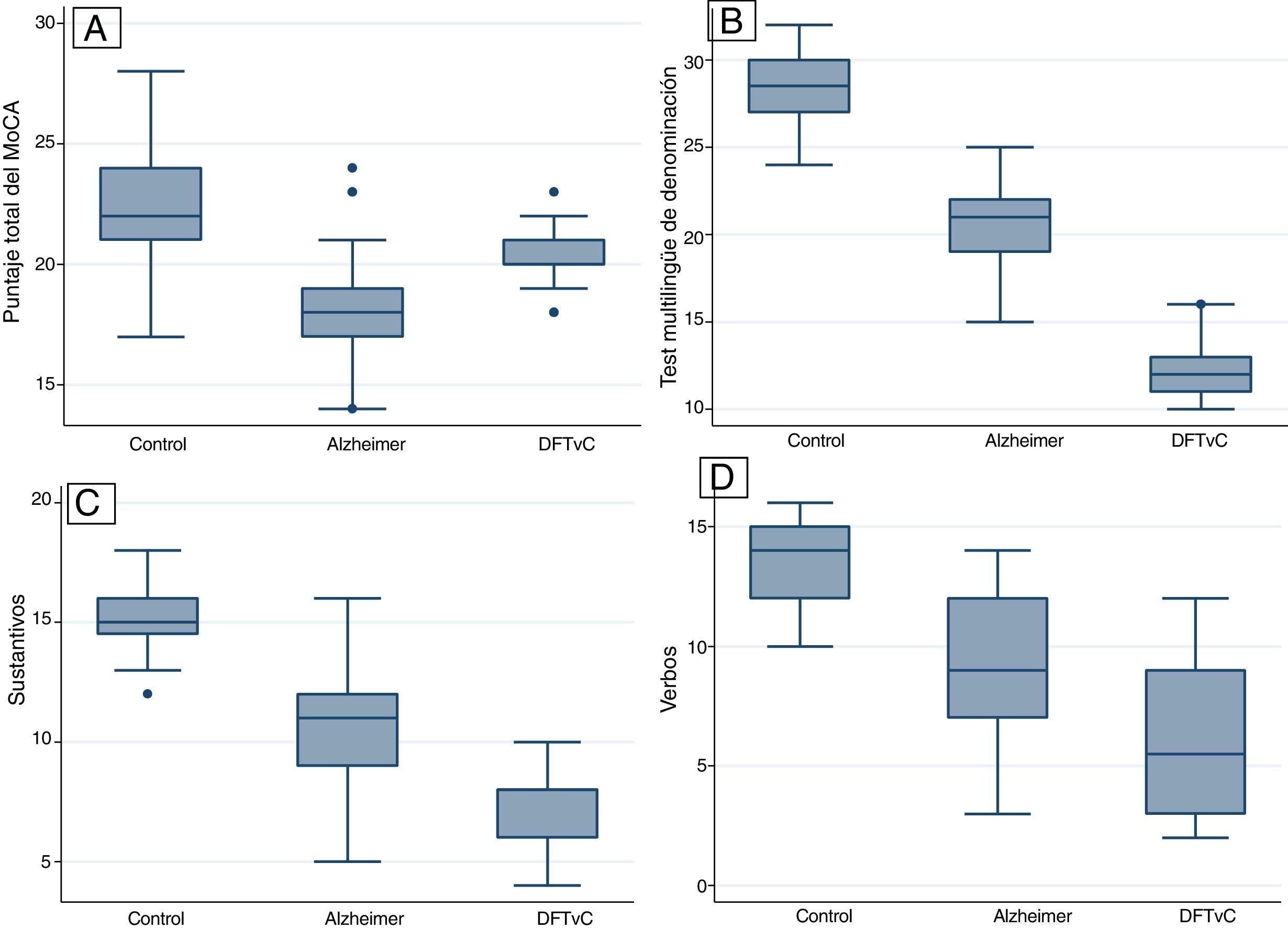

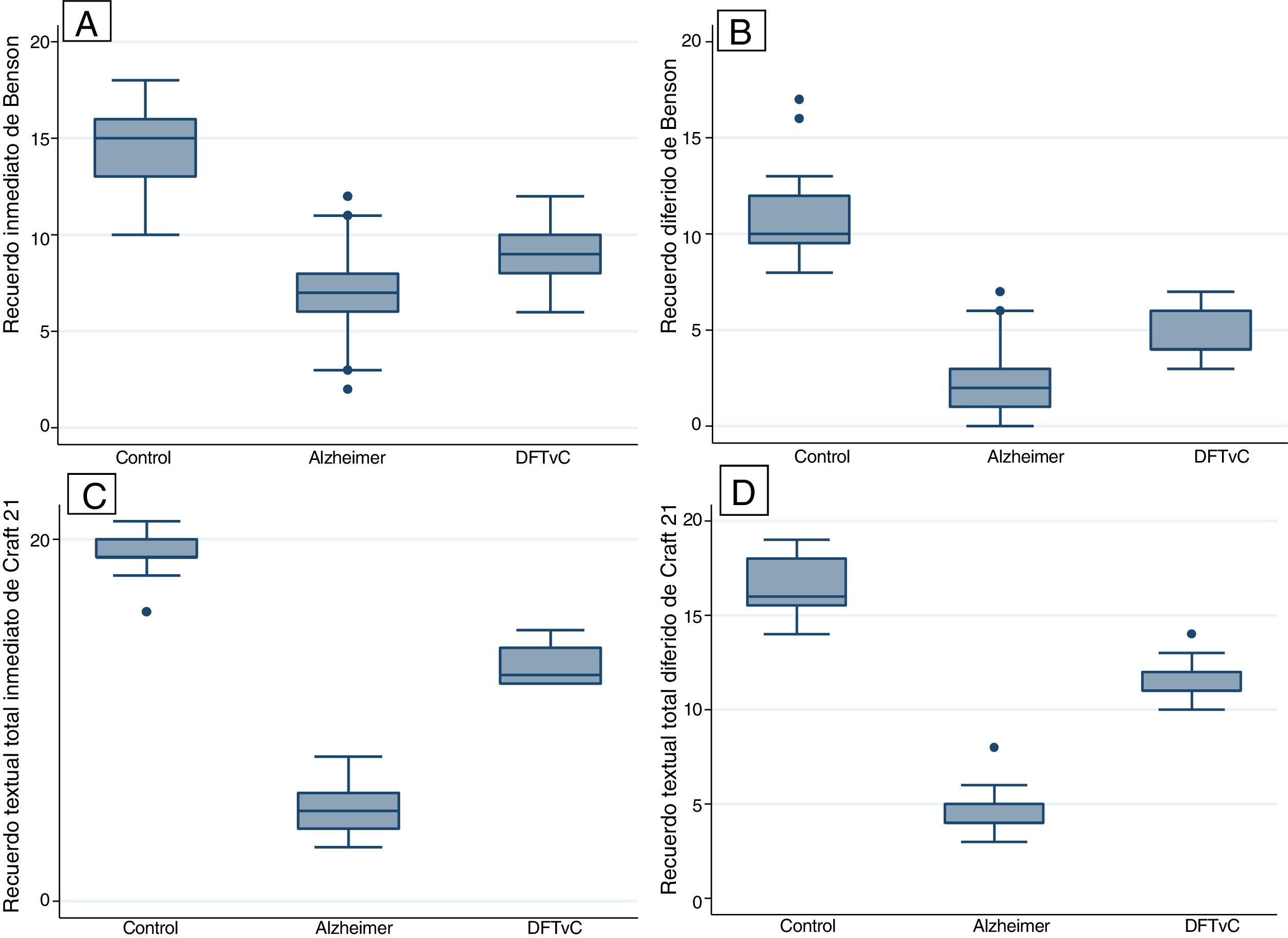

ResultsA higher average age was observed among the patients with AD. The naming capacity was much lower in patients with bvFTD compared to patients with AD, measured according to the MINT and the nouns/verbs naming coefficient. All patients with bvFTD, 73.81% of those with AD and only 31.25% of the control group failed to recognise Benson’s complex figure. All differences were statistically significant (p < 0.001).

ResultsThis study confirms the amnesic profile of patients with AD and reveals the decrease in naming capacity in patients with bvFTD, an area of language that is typically affected early on with executive functions, according to recent findings.

ConclusionsPatients with AD perform worse in verbal and visual episodic memory tasks, while patients with bvFTD perform worse in naming tasks. These findings open the possibility of exploring the mechanisms of prefrontal participation in episodic memory, typically attributed to the hippocampus.

Aunque la ausencia de deterioro de la memoria se consideró entre los criterios diagnósticos para diferenciar la enfermedad de Alzheimer (EA) de la demencia frontotemporal variante conductual (DFTvC), la evidencia actual, en aumento, señala un importante porcentaje de casos de DFTvC con déficits de la memoria episódica. El presente estudio se diseñó con el fin de comparar el perfil de desempeño de la capacidad denominativa y de la memoria episódica de los pacientes con EA y DFTvC.

MétodosEstudio transversal y analítico con grupo de control (n = 32). Se incluyó a 42 sujetos con probable EA y 22 con probable DFTvC, todos mayores de 60 años. Se utilizaron instrumentos del Uniform Data Set validados en español: Multilingual Naming Test (MINT), historia de Craft-21 y figura compleja de Benson, entre otros.

ResultadosSe observó un mayor promedio de edad entre los pacientes con EA. La capacidad denominativa fue mucho menor en los pacientes con DFTvC que en aquellos con EA, medida según el MINT y el coeficiente de denominación sustantivos/verbos. Todos los pacientes con DFTvC, el 73,81% de aquellos con EA y solo el 31,25% de los controles no lograron reconocer la figura compleja de Benson. Todas las diferencias fueron estadísticamente significativas (p < 0,001).

ResultadosEste estudio confirma el perfil amnésico de los pacientes con EA y revela la disminución de la capacidad denominativa de los pacientes con DFTvC, un área del lenguaje que se afecta típica y tempranamente con las funciones ejecutivas, según recientes hallazgos.

ConclusionesLos pacientes con EA rinden peor en las tareas de memoria episódica verbal y visual, mientras que los pacientes con DFTvC rinden peor en tareas de denominación. Estos hallazgos abren la posibilidad de explorar los mecanismos de participación prefrontal en la memoria episódica, típicamente atribuida al hipocampo.

The term “dementia” is defined as an acquired clinical syndrome caused by reversible or irreversible brain dysfunction. It is primarily characterised by serious decline in cognitive functions, commonly associated with psychiatric disorders, behavioural disorders or, in some cases, movement disorders that ultimately affect functional independence.1 With respect to subtypes of dementia, door-to-door studies in individuals 65 years of age and older in urban communities in Latin America found that Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was the most common (56.2%), followed by AD with cerebrovascular disease (CVD) (15.5%) and vascular dementia (VD) (8.7%).2 There have been few reports in our region of other degenerative causes of dementia, such as frontotemporal dementia (FTD). In studies in communities in Latin America in individuals 55 years of age and older, the prevalence of FTD has been found to be as high as 12-18 cases per 1,000 population, and higher in the Brazilian population (2.6%-2.8%) than in the Peruvian population (1.9%) or the Venezuelan population (1.53%).3 Regarding the clinical characteristics of AD, patients’ symptoms start as errors in episodic memory of recent events, followed by impairment of language and visual–spatial abilities, as well as difficulties with skilled movements, indicating the spread of cortical damage from the parahippocampal regions towards posterior association areas. FTD, for its part, is a syndrome characterised by gradual decline in behaviour or language, along with marked frontal and temporal lobe atrophy.1 FTD includes three different clinical phenotypes: behavioural variant, semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (PPA) and nonfluent/agrammatic variant PPA; the most common subtype is behavioural variant FTD (BvFTD).4 Patients with BvFTD show gradual changes in their personality and social behaviour. According to the consensus criteria,5 a diagnosis of possible BvFTD requires three of the following six characteristics: disinhibition, apathy/inertia, loss of empathy, perseveration/compulsive behaviours, hyperorality and a neuropsychological profile of executive dysfunction with relative preservation of episodic memory and visual–spatial abilities. A diagnosis of probable BvFTD further requires a decline in functioning and prominent signs of focal frontotemporal impairment on structural and functional neuroimaging (particularly in the orbitofrontal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex). A diagnosis of definitive BvFTD is reserved for patients with a known pathogenic genetic mutation or histopathological evidence of frontotemporal lobe degeneration. Despite discrepancies in neuropsychological patterns, there is a growing body of evidence on the typical dysexecutive pattern in patients in early-stage BvFTD4–6 and on the amnestic pattern in most patients with AD.7 In 2005, the United States National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centre (NACC) created the Uniform Data Set (UDS) to collect uniform clinical data on various degenerative forms of dementia. In April 2008, the UDS Neuropsychology Work Group was formed. This group recommended replacing the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA); the Logical Memory IA-Immediate Recall and IIA-Delayed Recall from the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (WMS-R) with the Craft Story 21 (Immediate and Delayed Recall); the Digit Span from the WMS-R with the Number Span; and the Boston Naming Test with the Multilingual Naming Test (MINT),8 whose version 3.0 in Spanish was implemented in March 2015.

The objective of this study was to conduct a comparative evaluation of performance in word capacity (MINT and naming of nouns and verbs) and episodic memory (Craft Story 21 and Benson Complex Figure Copy) in patients with AD and BvFTD with the version in Spanish of the UDS neuropsychological battery.

MethodsStudy designA cross-sectional analytical study was conducted in patients over 60 years of age who regularly visited the diagnostic unit for cognitive impairment and dementia prevention of the Instituto Peruano de Neurociencias [Peruvian Institute of Neurosciences] (IPN) between March 2017 and March 2019.

Study populationThree groups were studied: 32 control subjects, 42 subjects with a diagnosis of probable AD and 22 subjects with a diagnosis of probable BvFTD in mild to moderate stages, according to the results of the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR).9 The sample size was calculated for expected rates of AD of 50%10 and BvFTD of 2%,3 based on experience, and convenience sampling was performed until the sample size calculated was reached.

The inclusion criteria were: patients >60 years of age who met the diagnostic criteria for dementia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).11 Probable AD was diagnosed according to the criteria of the United States National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association,7 and BvFTD was diagnosed according to the criteria of the international consortium.5 The control group was made up of patients’ relatives and healthy volunteers. The exclusion criteria were: subjects with difficulty completing the cognitive tests due to hearing or vision problems or other physical problems that might have interfered with their performance; language other than Spanish; low level of education (defined as fewer than four years of education); score >4 on the criteria for the modified Hachinski scale; a diagnosis of depression; concomitant CVD; a history of substance addiction or abuse; or cognitive impairment explained by another cause, such as hypothyroidism, Vitamin B12 deficiency, liver disease, chronic kidney disease, neurological infections (human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection or syphilis), serious traumatic brain injury or subdural haematoma.

Clinical and neuropsychological evaluationThe subjects underwent the following successive evaluations (screening, and diagnosis of dementia and type of dementia) in each phase. During the screening phase, the patients underwent a comprehensive clinical evaluation and brief cognitive tests, including: the MMSE,12 the clock-drawing test-Manos’ version (CDT-M)13 and the Pfeffer Functional Activities Questionnaire (PFAQ).14 Individuals with responses below the scores established for this research protocol proceeded to a second evaluation, in which new MMSE and CDT-M tests were administered by an evaluator other than the one who led the screening phase.

The cut-off point on the MMSE for suspected dementia was adjusted for years of education: 27 for those with more than seven years, 23 for those with four to seven years, 22 for those with one to three years and 18 for those with no education.10

The CDT-M evaluates the individual's ability to place the numbers 1-12 inside a circle as on a clock and then assesses the direction and proportionality of the hands of the clock when the individual tries to set them to 11:10 AM. The maximum score is 10 points, and in Peruvians a score <7 indicates cognitive impairment.14

The PFAQ includes 11 questions on activities of daily living, with scores from 0 to 3 depending on the seriousness of the individual’s disability in each activity. A score of more than 6 points indicates functional impairment; the maximum score is 33 points.

Individuals with “cognitive impairment” confirmed in the second round of tests had samples drawn for a complete blood count (haemoglobin; glucose; urea; creatinine; liver function tests [aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT)]; serum levels of albumin and globulin, Vitamin B,12 and folic acid; venereal disease research laboratory test [VDRL] to rule out syphilis; enzyme-linked immunoassay [ELISA] to rule out HIV infection; thyroid panel [triiodothyronine (T3), thyroxine (T4) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)]; and serum sodium, potassium and chloride electrolytes). These individuals also underwent computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, and an evaluation of symptoms of depression (Beck Depression Inventory [BDI]-II), to rule out pseudodementia. A certified evaluator blinded to the brief cognitive tests applied the CDR9 to classify their stage of dementia. In the final phase, with the results of the blood tests, brain imaging and neuropsychology report, the type of dementia was diagnosed by consensus between the neurologists and neuropsychologists on the team. The UDS neuropsychological battery consisted of the following tests: the MoCA, Craft Story 21-Immediate Recall, Benson Complex Figure Copy (Immediate Recall), Digit Span Forward and Backward, category fluency, Trail Making Test Parts A and B, Craft Story 21-Delayed Recall, Benson Complex Figure Copy (Delayed Recall), MINT, and verbal fluency test. The Craft Story 21 consists of reading a story, after which the individual evaluated must remember (immediate recall) as many words as possible from the story: “Maria’s child Ricky played soccer every Monday at 3:30. He liked going to the field behind their house and joining the game. One day he kicked the ball so hard that it went over the neighbour’s fence where three large dogs lived. The dogs’ owner heard loud barking, came out and helped them retrieve the ball.” The individual evaluated is instructed to try not to forget it, then after approximately 20 minutes will be asked to retell the story (delayed recall). For the Benson Complex Figure Copy, the individual is given a figure printed on a sheet of paper and asked to copy the design (immediate recall). After they have finished the drawing, they are asked to remember this design because later on (in approximately 10-15 minutes) they will be asked to draw it again from memory (delayed recall). In addition, the patient is shown four figures, one of which is the figure they copied and remembered, and is asked to recognise the original stimulus among the four options (recognition of the Benson Complex Figure Copy). For the Forward Digit Span test, the individual is asked to repeat a series of larger and larger numbers in the same order. For the Backward Digit Span test, the individual is asked to repeat a series of numbers of larger and larger numbers in the opposite of the order in which the evaluator states them. In the category fluency test, the individual is asked to name all the animals they can in one minute, then is asked to name all the vegetables they can in one minute. For the Trail Making Test Part A, the individual is shown a sheet printed with various numbers inside of circles distributed in a random order and is asked to draw a line from one circle to another in ascending order, starting with the number 1 and ending with the number 25. For the Trail Making Test Part B, the individual is shown a sheet printed with various numbers and letters inside of circles distributed in a random order and asked to draw a line from one circle to another in ascending order, alternating between numbers and letters, starting with the number 1 and ending with the number 13. In the MINT, the individual is shown drawings of objects (32 items), one each time, and is asked to state each object's name. Finally, for the verbal fluency test, the patient is asked to name all the words starting with the letter P they can in one minute, then is asked to do the same but with the letter M.

Study variablesFor the MINT, the total score for correctly named objects out of up to 32 points was used; this score was obtained after adding up the total number of named objects without a semantic cue and the total number of named objects with a cue.

For naming of nouns and verbs, the total score for correctly named nouns and verbs was used, and the noun-to-verb ratio was also reported.

For immediate and delayed recall in the Benson Complex Figure Copy, the total score obtained following evaluation of each figure element, out of up to 17 points, was recorded. In addition, recognition of the Benson Complex Figure Copy was reported dichotomously.

For the Craft Story 21, for both immediate and delayed recall, the total units remembered (verbatim score) and the total units remembered with paraphrasing (paraphrase score) were recorded.

Data analysisAbsolute and relative frequencies were calculated for the categorical variables, and measures of central tendency and standard deviation were calculated for the continuous variables. The normal distribution of the continuous variables was determined using a graph or statistical test. Comparison tests were performed between the categories determined by the results for the patients from the control, AD (early and late) and BvFTD groups for the categorical variables using the χ2 test (recognition of the Benson Figure) and for the continuous variables (age, MoCA score, score on naming tests, immediate recall and delayed recall for the Craft Story 21 and Benson Complex Figure Copy) using analysis of variance (ANOVA). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated. The Stata software program, ver. 14 (StataCorp LP, United States), was used.

Ethical considerationsThe privacy and anonymity of each of the participants, who granted their informed medical consent, were respected. The approval of the Hospital Nacional Docente Madre Niño San Bartolomé [San Bartolomé Peruvian National Maternal–Child Teaching Hospital] independent ethics committee was obtained.

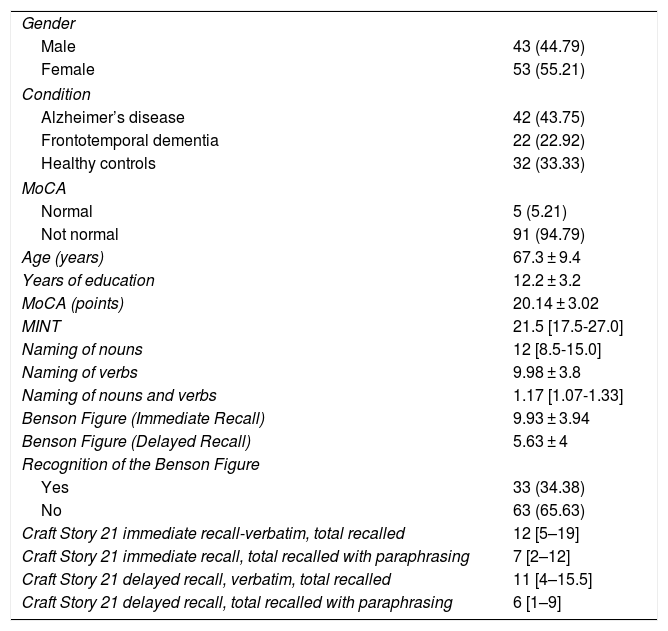

ResultsA total of 96 participants were evaluated: 42 participants with AD, 22 participants with BvFTD and 32 healthy controls. The majority were women, with a mean age of 67.3 years. Table 1 also shows the participants’ average results for different cognitive tests, such as the MoCA, MINT, naming of verbs and nouns, Benson Complex Figure Copy, immediate and delayed recognition; and Craft Story 21. The score obtained on the MoCA, according to recommendations from the authors, does not reflect the cognitive status of the controls.

General characteristics of the population studied.

| Gender | |

| Male | 43 (44.79) |

| Female | 53 (55.21) |

| Condition | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 42 (43.75) |

| Frontotemporal dementia | 22 (22.92) |

| Healthy controls | 32 (33.33) |

| MoCA | |

| Normal | 5 (5.21) |

| Not normal | 91 (94.79) |

| Age (years) | 67.3 ± 9.4 |

| Years of education | 12.2 ± 3.2 |

| MoCA (points) | 20.14 ± 3.02 |

| MINT | 21.5 [17.5-27.0] |

| Naming of nouns | 12 [8.5-15.0] |

| Naming of verbs | 9.98 ± 3.8 |

| Naming of nouns and verbs | 1.17 [1.07-1.33] |

| Benson Figure (Immediate Recall) | 9.93 ± 3.94 |

| Benson Figure (Delayed Recall) | 5.63 ± 4 |

| Recognition of the Benson Figure | |

| Yes | 33 (34.38) |

| No | 63 (65.63) |

| Craft Story 21 immediate recall-verbatim, total recalled | 12 [5–19] |

| Craft Story 21 immediate recall, total recalled with paraphrasing | 7 [2–12] |

| Craft Story 21 delayed recall, verbatim, total recalled | 11 [4–15.5] |

| Craft Story 21 delayed recall, total recalled with paraphrasing | 6 [1–9] |

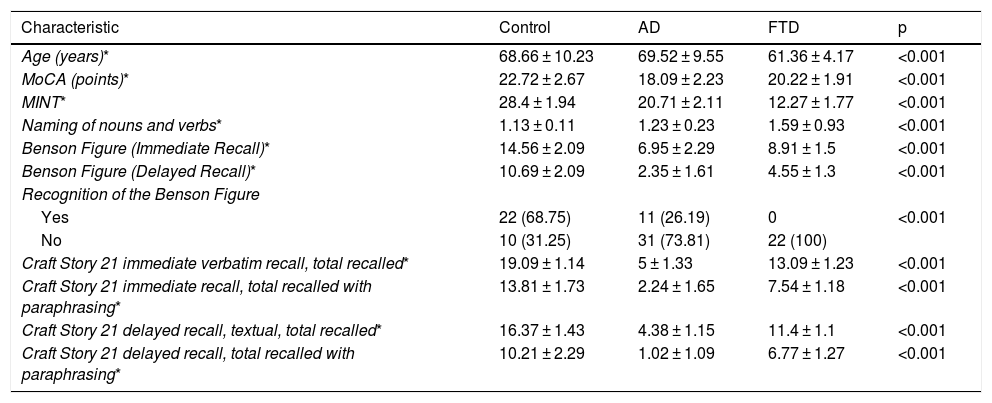

Statistical differences were found between the three study groups (healthy controls, AD and BvFTD) in the variables of age and score on the different tests: the MoCA, MINT; naming of verbs and nouns; Benson Complex Figure Copy, immediate and delayed recognition; and Craft Story 21 (Table 2).

Differences between word capacity and episodic memory scores of patients with AD and BvFTD.

| Characteristic | Control | AD | FTD | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 68.66 ± 10.23 | 69.52 ± 9.55 | 61.36 ± 4.17 | <0.001 |

| MoCA (points)* | 22.72 ± 2.67 | 18.09 ± 2.23 | 20.22 ± 1.91 | <0.001 |

| MINT* | 28.4 ± 1.94 | 20.71 ± 2.11 | 12.27 ± 1.77 | <0.001 |

| Naming of nouns and verbs* | 1.13 ± 0.11 | 1.23 ± 0.23 | 1.59 ± 0.93 | <0.001 |

| Benson Figure (Immediate Recall)* | 14.56 ± 2.09 | 6.95 ± 2.29 | 8.91 ± 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Benson Figure (Delayed Recall)* | 10.69 ± 2.09 | 2.35 ± 1.61 | 4.55 ± 1.3 | <0.001 |

| Recognition of the Benson Figure | ||||

| Yes | 22 (68.75) | 11 (26.19) | 0 | <0.001 |

| No | 10 (31.25) | 31 (73.81) | 22 (100) | |

| Craft Story 21 immediate verbatim recall, total recalled* | 19.09 ± 1.14 | 5 ± 1.33 | 13.09 ± 1.23 | <0.001 |

| Craft Story 21 immediate recall, total recalled with paraphrasing* | 13.81 ± 1.73 | 2.24 ± 1.65 | 7.54 ± 1.18 | <0.001 |

| Craft Story 21 delayed recall, textual, total recalled* | 16.37 ± 1.43 | 4.38 ± 1.15 | 11.4 ± 1.1 | <0.001 |

| Craft Story 21 delayed recall, total recalled with paraphrasing* | 10.21 ± 2.29 | 1.02 ± 1.09 | 6.77 ± 1.27 | <0.001 |

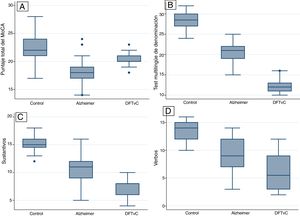

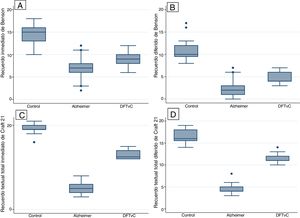

A higher mean age was in the AD group compared to the BvFTD and control groups. Performance on the MoCA was lower among the patients with AD than among the patients with BvFTD and the controls. Word capacity was much lower in patients with BvFTD than in those with AD, measured according to the MINT and the noun-to-verb naming ratio (Fig. 1, Table 2 and Table 3). In addition, the patients with AD had poorer performance according to their visual episodic memory score measured based on the Benson Complex Figure Copy, immediate and delayed recall, and their verbal episodic memory score measured based on immediate and delayed recall, for both the verbatim score and the paraphrase score, for the Craft Story 21 (Fig. 2, Tables 2 and 3).

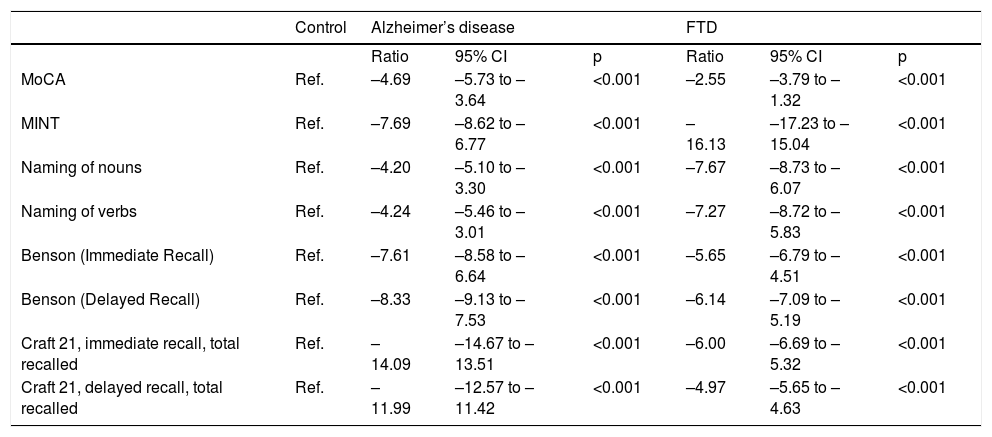

Ratios according to scores and diagnosis of AD or BvFTD.

| Control | Alzheimer’s disease | FTD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio | 95% CI | p | Ratio | 95% CI | p | ||

| MoCA | Ref. | –4.69 | –5.73 to –3.64 | <0.001 | –2.55 | –3.79 to –1.32 | <0.001 |

| MINT | Ref. | –7.69 | –8.62 to –6.77 | <0.001 | –16.13 | –17.23 to –15.04 | <0.001 |

| Naming of nouns | Ref. | –4.20 | –5.10 to –3.30 | <0.001 | –7.67 | –8.73 to –6.07 | <0.001 |

| Naming of verbs | Ref. | –4.24 | –5.46 to –3.01 | <0.001 | –7.27 | –8.72 to –5.83 | <0.001 |

| Benson (Immediate Recall) | Ref. | –7.61 | –8.58 to –6.64 | <0.001 | –5.65 | –6.79 to –4.51 | <0.001 |

| Benson (Delayed Recall) | Ref. | –8.33 | –9.13 to –7.53 | <0.001 | –6.14 | –7.09 to –5.19 | <0.001 |

| Craft 21, immediate recall, total recalled | Ref. | –14.09 | –14.67 to –13.51 | <0.001 | –6.00 | –6.69 to –5.32 | <0.001 |

| Craft 21, delayed recall, total recalled | Ref. | –11.99 | –12.57 to –11.42 | <0.001 | –4.97 | –5.65 to –4.63 | <0.001 |

Coef.: coefficient; 95%CI: confidence interval of 95%; Ref.: reference.

All differences were statistically significant (p < 0.001). All patients with BvFTD and 73.81% of subjects with AD, as well as 31.25% of the controls, did not manage to recognise Benson Complex Figure.

DiscussionThe sample studied had a median level of education of 12.2 ± 3.2 years. This was consistent with studies conducted in Lima on dementia14,15 and FTD,16–18 in which the populations studied had 11 years of education on average. In addition, the sample of patients with AD was older than that of patients with BvFTD, in line with prior studies conducted in Latin America3,19,20 and Peru,16–18 as BvFTD usually presents in middle age, with an onset around age 58.4,6

This study confirmed the amnestic profile of patients with AD1,7 and revealed a decrease in word capacity in patients with BvFTD. According to recent findings,21 this area of language is affected typically and early with executive functions. Our series of patients with AD showed a serious decline in verbal episodic memory (evaluated by immediate and delayed recall of the Craft Story 21) and visual episodic memory (evaluated by immediate and delayed recall and recognition of the Benson Complex Figure), which is also affected in patients with BvFTD, but with a very significant difference. Episodic memory in patients with dementia often used to be evaluated by having them learn a list of words and recall stories using logical memory;22,23 however, the NACC UDS has recommended the Craft Story 21 and the Benson Complex Figure Copy since 2008.8,23 Craft et al.25 had designed multiple forms of recall of 22 stories similar to those used in logical memory in a study of the impact of insulin on cognition in patients with early-stage AD; the UDS Neuropsychology Work Group, after various pilot tests, decided to include only story 21, known today as the Craft Story 21. Visual–spatial abilities decline early in amnestic forms of AD, and may be affected early in other clinical syndromes of AD, such as posterior cortical atrophy and cortical Lewy body dementia.1 Therefore, the NACC UDS recommended including the Benson Complex Figure in the evaluation of neurodegenerative forms of dementia.24 In addition, different performance profiles and a clear association with frontal and parietal regional atrophy have been demonstrated in patients with FTD and AD.25,26 Episodic memory has been found to be typically preserved in patients with early-stage BvFTD; however, there is a growing body of evidence that a certain percentage of cases of BvFTD, such as cases with pathology confirmation, may present with a marked deficit in episodic memory27,28 and are characterised by impairment of classic memory tasks based on immediate and delayed recall, with relative preservation of recognition memory.29,30 Other studies have found patients with BvFTD and patients with AD to show comparable decline.30,31 The reasons for these discrepancies are not clear, but could be attributed to a number of factors, such as different stages in disease progression, the type of memory evaluated and the inclusion in studies of BvFTD with progression, known as phenocopies.28,30,32 These findings open up the possibility of exploring the mechanisms of prefrontal involvement in episodic memory, typically attributed to the hippocampus.28,33

While patients with BvFTD do typically present social disintegration and personality changes,4–6 there is substantial phenotypic overlap with other entities, in particular PPA, even in early-stage BvFTD.4,34,35 Deficiencies in confrontation naming,37–39 understanding of isolated words40 and phrases,41 and semantic abilities41,42 have been reported. In addition, frontotemporal atrophy often overlaps with abnormalities in language neural networks,43,44 and the neuroanatomical evidence available has linked abnormalities in the frontal, temporal and parietal circuits to the genesis of the language deficiencies in this syndrome.21,36 Thus, the decline in the cortical networks that mediate semantic verbal processing may account for the linguistic profile of patients with BvFTD;21,35 therefore, proper evaluation of language is required in this syndrome. The NACC UDS Neuropsychology Work Group selected the 32-item MINT to replace the short (30-item) version of the Boston Naming Test (BNT). The MINT was originally developed as naming test in four languages: English, Spanish, Hebrew and Mandarin Chinese. A cross-sectional study8 showed good correlation between the BNT and the MINT (r = 0.76). Preliminary normative data from the UDS for the MINT were later published,24 and recently the MINT detected deficiencies in the naming of different degrees of cognitive impairment in patients with mild cognitive impairment and AD dementia, though they must be corrected for age, gender, race and level of education.45

One of the main limitations of this study was its sample size, which might not have been large enough to yield more accurate estimates. In addition, it is recognised that the participants were sampled from a specialised dementia unit, which could limit the extent to which the results can be generalised. A second anticipated limitation was related to the risk of misclassifications in the study groups (control, BvFTD and AD), since the cross-sectional design of the study precluded longitudinal follow-up of each case to accurately determine diagnoses in each group. Furthermore, pathology studies of samples of brain tissue to establish definitive diagnoses could not be conducted. The fact that type of dementia was diagnosed based on clinical judgement, in addition to blood tests and brain imaging, but not biomarkers in blood or cerebrospinal fluid, was identified as a third limitation. However, diagnosis was based on a comprehensive evaluation and by consensus of a multidisciplinary team of experienced clinicians, for whom structured clinical diagnosis served as a standard in this study. The clinicians based their clinical diagnosis on the information available from the visit on the first day of evaluation in the community, i.e., the information from the medical history and the structured interview, clinical examination (neurological and psychiatric), medical history and, later on, information from standardised cognitive and functional tests performed by specialists in cognitive evaluation at the specialised memory centre of the IPN. A fourth limitation of this study was that the participants were from an urban area, spoke and understood Spanish as their native language or were bilingual, and had been speaking and understanding Spanish as a second language for more than 10 years. This means that the results probably better reflected the performance of the UDS battery in this linguistic group than in a rural population or a population whose exclusive or predominant language is not Spanish (e.g., Quechua or Aymara); the behavior of the UDS battery in such populations is not known. It would be important to determine the probable influence of culture and bilingualism.

ConclusionsPatients with AD show poorer performance on verbal and visual episodic memory tasks, whereas patients with BvFTD show poorer performance on naming tasks. In addition, the version in Spanish of the UDS neuropsychological battery can be used in patients with median levels of education.

Please cite this article as: Custodio N, Montesinos R, Cruzado L, Alva-Díaz C, Failoc-Rojas VE, Celis V, et al. Estudio comparativo de la capacidad denominativa y la memoria episódica de los pacientes con demencia degenerativa. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2022;51:8–16.