Shared paranoid disorder is characterised by the development of psychotic symptoms in people who have a close affective bond with a subject suffering from a mental disorder. This case is the first case of burn injuries reported in the context of this disorder.

CaseWe describe a young couple, with a similar pattern of burns caused by contact with a griddle. The injuries are the result of the aggression caused by a relative of one of them, who presented psychotic symptoms, related to the previously undiagnosed spectrum of schizophrenia.

ConclusionsThe impact of this condition encompasses social, physical and psychological components, requiring multidisciplinary management and a high index of diagnostic suspicion.

El trastorno psicótico compartido se caracteriza por la aparición de síntomas psicóticos en personas que tienen un vínculo afectivo estrecho con un sujeto que padece un trastorno mental; este caso es el primer reporte de lesiones por quemaduras en el contexto de este trastorno.

CasoSe trata de una pareja joven, con un patrón similar de quemaduras causadas por el contacto con una plancha. Las lesiones son el resultado de la agresión causada por un familiar de uno de ellos, que presentaba síntomas psicóticos relacionados con el espectro de esquizofrenia no diagnosticado previamente.

ConclusionesEl impacto de esta afección abarca los componentes social, físico y psicológico y requiere un tratamiento multidisciplinario y un alto índice de sospecha diagnóstica.

Shared psychotic disorder (SPD) is an uncommon illness, with little clinical recognition, therefore requiring a high index of clinical suspicion. It was described as a mental “contagion” in 1651,1 and in 1877 the term folie à deux or communicated insanity was introduced and the characteristics of the disorder were established.1–3 In 1880, the three fundamental criteria for diagnosis were determined: a) a close relationship between the subjects; b) identical or very similar content of the delusions in the individuals, and c) the subjects share and accept each other’s delusions.4,5

Induced delusional disorder (ICD-10) or SPD (DSM-4) may involve two (folie à deux) or, very rarely, more individuals, but is then reported as folie à trois, folie à quatre, folie à cinq or folie famille.4,6

In recent DSMs, it was referred to as SPD because it concerned people who developed delusions similar to those of a close relative or peer. The second individual’s delusions were often resolved once the relationship with the first individual was severed. There are several reasons why this condition was excluded from the DSM-5. For decades there has been very little research that could help in understanding SPD, and only case reports; while most of these patients live with someone who has schizophrenia or delusional disorder, the phenomenon has also been linked to dissociative disorders and obsessive compulsive disorder; most patients who would have previously received a diagnosis of folie à deux (SPD) meet the criteria for delusional disorder, which is the category in which they must now be grouped in the DSM-5. Otherwise, another specified psychotic disorder would have to be diagnosed and the reasons would have to be explained.

Its incidence ranges from 1.7% to 2.6% of the population.2 Some 73%–81% of cases involve two individuals. The largest group reported has been 12 people.5,7

Case reportFemale patient A was admitted to the institution in labour, and had a full-term newborn without complications. She presented with intermediate and deep second-degree burns on 18% of her total body surface area (TBSA), located on her trunk and extremities (Fig. 1); she initially reported boiling oil as the cause, but the lesions showed a pattern indicating contact burns (Fig. 2), so she was confronted, and she stated that her sister had burned her with an iron. Patient A reported that female patient C had been living with her and male patient B for three months. During this period, she observed restlessness, difficulty sleeping and changes in behaviour in patient C; she stated that the colour of her eyes and the tone of her voice were different. “She seemed like another person, she spoke differently, she had supernatural strength, her eyes were glassy and opaque”, which she attributed to “demonic possession”. She said that when she was close to patient C, she was afraid of losing her pregnancy, which is why she agreed to let patient C burn her with the iron, on the grounds that it was the only way to expel “Satan” from her body.

She was hospitalised for 26 days, with subjective certainty and conviction about what she had reported, but during the last week she questioned what had happened; she considered that her sister might be “sick in the head”.

Patient B was admitted 6 days after being burned with an iron, with intermediate and deep second-degree burns involving 11% of the TBSA on his trunk and extremities (Fig. 3). Patient B reported that the burns were caused by patient C, whom he described as sad and withdrawn (“she kept crying and locked herself in her room”). He also described changes in her behaviour and stated that at times patient C seemed to him “as if she were a compassionate and loving angel”, but at other times he saw her as a demon (“she spoke strangely, she had a lot of strength, as if someone else was in her body, she said she was going to take my wife and my son”), a situation he attributed to her being “possessed”. He commented that it frightened him, because patient C verbalised in vociferous language “that she was a portal between God and hell”, and he feared that she would fulfil the prophecy of taking his family with her, which is why he did not resist when she was burning him with the iron.

On leaving the institution, he had a delusional memory of what had happened, and expressed doubts about the possibility that patient C had really been possessed.

To treat the burns, every other day patients A and B received dressings and coverage of the more deeply burned areas with split-thickness grafts on day 21 post-burn, with very good results.

Patient C is a 20-year-old female. She has had complex command auditory hallucinations since she was eight years old. In early adolescence, she was abused by her stepfather, and although she brought this situation to her mother's attention, she was not believed, and from then on she became withdrawn and suffered from insomnia, muscle fatigue and poor academic performance. She described periods of sadness and thoughts of death, which were accompanied by impulsive suicide attempts. At the age of 16, she started using cannabis, without specifying her pattern of use. After breaking up with her partner, she moved in with patients A and B. She again exhibited sad mood, emotional lability, sleep maintenance insomnia, hyporexia, visual and tactile hallucinations, and mystical and self-referential delusions; she also reported recurrent thoughts of death and structured suicidal ideation. She stated that on the day she assaulted patients A and B, she heated the iron and burnt them but did not remember precisely what happened, and described reduced consciousness. During hospitalisation, when asked about other similar behaviour, she described previous assaults on other family members and even stated her intention to burn down her parents’ house to ward off the demon. It was concluded that patient C had a depressive subtype schizoaffective disorder. She was treated in the psychiatric hospital and discharged with antipsychotics; she attended check-ups and remission of positive symptoms was achieved; patients A and B live separately from patient C and patient A occasionally telephones her.

DiscussionThis case is the first report of burns related to SPD. In SPD, the primary case is the individual presenting with the original delusion, who influences another individual, called the secondary case, the majority of whom are women. In total, 64% of secondary cases occur in family members with first degree of consanguinity,2 as is the case with patients A and C. Secondary patients may subsequently develop a psychotic disorder, typically schizophreni.8

Due to the tendency of collective behaviour to imitate attitudes, movements and expressions, the idea of an emotional “contagion” is sustained.9 The changes in patient C’s behaviour become the main focal point of coexistence and mark a change in the family dynamics that generates delusions and acceptance of patient C’s behaviours by A and B.

The development of Patient C’s psychotic symptoms are the result of multiple factors: exposure to sexual abuse during childhood or adolescence,10 socio-economic stressors and changes in her interpersonal relationship,11,12 schizoid personality traits and cannabis use.13 Patient C, who did not receive early treatment, had a worsened prognosis, due to affective, positive, negative and social deterioration symptoms.14 Some of the divergences found include the fact that patient C does not fit the biotype of a primary patient, she does not have an imposing character or a higher academic level or intelligence; furthermore, the patients were not in isolation.

The appearance of SPD can be attributed to difficulties in separation-individuation processes,15 the development of archaic defence mechanisms such as projection and identification, and delusions may also be an attempt by the individual to explain incomprehensible experiences.16,17

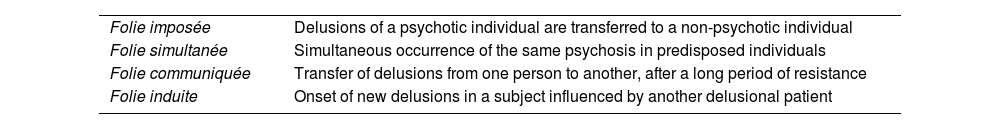

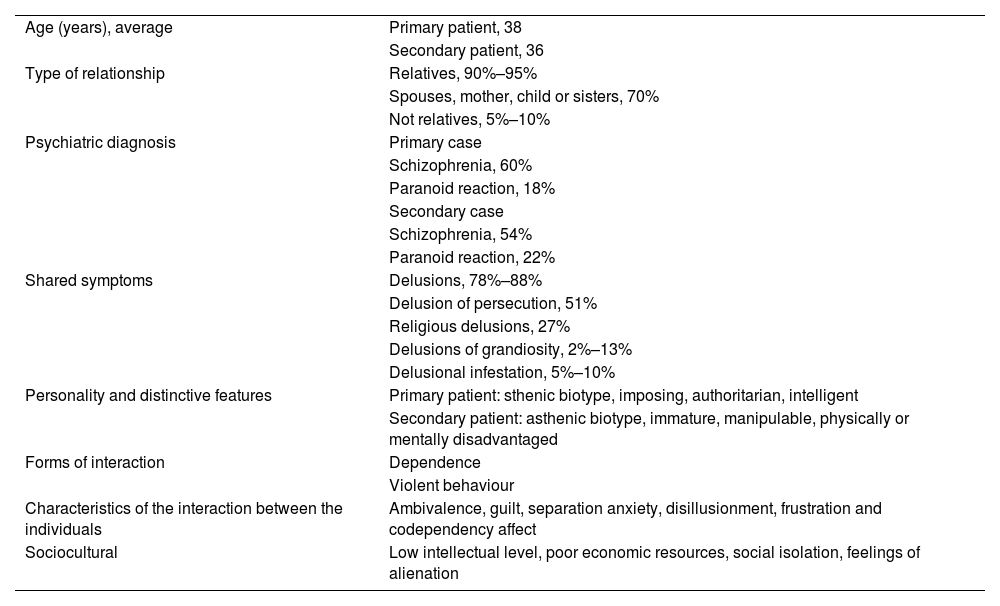

The classification of SPD subtypes is presented in Table 1 and the main characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Classification of the subtypes of shared psychotic disorder.3,4,17

| Folie imposée | Delusions of a psychotic individual are transferred to a non-psychotic individual |

| Folie simultanée | Simultaneous occurrence of the same psychosis in predisposed individuals |

| Folie communiquée | Transfer of delusions from one person to another, after a long period of resistance |

| Folie induite | Onset of new delusions in a subject influenced by another delusional patient |

Common clinical features of shared psychotic disorder.3,8

| Age (years), average | Primary patient, 38 |

| Secondary patient, 36 | |

| Type of relationship | Relatives, 90%–95% |

| Spouses, mother, child or sisters, 70% | |

| Not relatives, 5%–10% | |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | Primary case |

| Schizophrenia, 60% | |

| Paranoid reaction, 18% | |

| Secondary case | |

| Schizophrenia, 54% | |

| Paranoid reaction, 22% | |

| Shared symptoms | Delusions, 78%–88% |

| Delusion of persecution, 51% | |

| Religious delusions, 27% | |

| Delusions of grandiosity, 2%–13% | |

| Delusional infestation, 5%–10% | |

| Personality and distinctive features | Primary patient: sthenic biotype, imposing, authoritarian, intelligent |

| Secondary patient: asthenic biotype, immature, manipulable, physically or mentally disadvantaged | |

| Forms of interaction | Dependence |

| Violent behaviour | |

| Characteristics of the interaction between the individuals | Ambivalence, guilt, separation anxiety, disillusionment, frustration and codependency affect |

| Sociocultural | Low intellectual level, poor economic resources, social isolation, feelings of alienation |

In the case presented, separating the individuals allowed for the delusions to be resolved. A separation period of at least six months is recommended.18 Antipsychotics can be prescribed to primary and secondary patients.3,19–21

The importance of such cases also lies in their legal, ethical and social implications, given the reported fatal outcomes, such as homicides.22 Kraya et al. report five cases: two homicides of infants committed by their parents; a third case includes the homicide of two children, the suicide of the father and the attempted suicide of the mother; in the fourth case they describe serious personal injuries caused by a mother to her daughter; and the last case is that of twins who devised the homicide of their father (they did not go through with it, but burned down a farm on his property).22

Scott presents the killing of a police officer by a mother and her teenage son.23 Bourgeois et al. report the attempted murder and personal injury of the general practitioner of a woman with delusional parasitosis24 and the homicide of a woman at the hands of her two adolescent daughters.25–27

Deep burns can exacerbate underlying psychological problems and/or lead to secondary mental disorders, such as peritraumatic dissociation, delirium post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder.28 Contact burns are common,29 affect mainly the extremities and may require skin dressing and prolonged hospitalization.30

ConclusionsSPD is a rare disorder but it has a great social impact because it is associated with aggression towards oneself or others.

High clinical suspicion should be raised in the accident and emergency department when finding a similar pattern of injury, with conflicting narratives about the events, in individuals with a close emotional bond.

Given the complexity of the diagnostic and therapeutic approach, a multidisciplinary team is required; identifying the inducing patient, distancing them from the induced cases and initiating specific pharmacological treatment personalised for each of the members involved with the psychotherapeutic approach, as well as assertive communication with the family or social circle affected by the dysfunctional dynamic that was generated.

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that they have followed their institution's protocols on the publication of patient data.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.