The main aim of this study is to determine the prevalence of behavioural disturbances (BD) in a group of patients with diagnosis of neurocognitive disorders assessed by a memory clinic in a referral assessment centre in Bogotá, Colombia, in 2015.

Material and methodsThis is an observational, retrospective descriptive study of 507 patients with a diagnosis of neurocognitive disorder (according to DSM-5 criteria) evaluated in a referral centre in Bogotá, Colombia, in 2015.

ResultsAmong the group of patients assessed, analyses reveal mean age for minor neurocognitive disorders of 71.04 years, and 75.32 years for major neurocognitive disorder (P < 0.001). A total of 62.72% of the sample were female. The most prevalent aetiology of the neurocognitive disorders was Alzheimer’s disease, followed by behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia and neurocognitive disorders due multiple aetiologies. BD occur more frequently in neurocognitive disorder due to behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia (100%), Alzheimer’s disease (77.29%) and vascular disease (76.19%). The most prevalent BD in the group assessed were apathy (50.75%), irritability (48.45%), aggression (16.6%), and emotional lability (14.76%).

ConclusionsBD occur more frequently in patients with diagnosis of major neurocognitive disorder. BD are more prevalent in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia than any other group. Apathy, irritability, emotional lability and aggression are the BD that occur with greater prevalence in our sample. We discuss the importance of BD in the clinical progression of neurocognitive disorders.

El objetivo de este estudio es determinar la frecuencia de alteraciones conductuales (AC) en un grupo de pacientes con diagnóstico de trastorno neurocognoscitivo (TN) valorado por clínica de memoria en un centro de evaluación en Bogotá, Colombia, durante el año 2015.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional descriptivo y de corte retrospectivo de 507 pacientes con diagnóstico de trastorno neurocognoscitivo (según criterios del DSM-5), valorados en un centro de referencia en Bogotá en 2015.

ResultadosLa media de edad de los sujetos con trastorno neurocognoscitivo leve en el momento del diagnóstico era 71,04 años y la de aquellos con trastorno neurocognoscitivo mayor, 75,32 años (p < 0,001). El 62,72% de la muestra son mujeres. La etiología más frecuente del trastorno neurocognoscitivo fue la enfermedad de Alzheimer probable, seguida por la degeneración lobar frontotemporal, variante conductual, y el trastorno neurocognoscitivo debido a múltiples etiologías. Las AC se presentan con mayor frecuencia en TN debido a degeneración frontotemporal variante conductual (100%), enfermedad de Alzheimer (77,29%) y vascular (76,19%). Las AC más prevalentes en el grupo evaluado fueron la apatía (50,75%), la irritabilidad (48,45%), la agresividad (16,6%) y la labilidad emocional (14,76%).

ConclusionesLas AC suelen aparecer en pacientes con diagnóstico de trastorno neurocognoscitivo mayor. Según la etiología del trastorno neurocognoscitivo mayor, las AC son más prevalentes en la degeneración frontotemporal variante conductual. Apatía, irritabilidad, labilidad emocional y agresividad son las AC más comunes en toda la muestra.

In 2015, major neurocognitive disorder (MaND) affected 47 million people in the world, 60% of whom lived in low- and medium-income countries.1 It is estimated that, in 2030, more than 75 million people will have some sign of MaND. This figure is projected to have tripled by 2050.1 In general, neurocognitive disorder (ND) is divided into mild neurocognitive disorder (MiND) or major neurocognitive disorder (MaND), and has replaced the term "dementia" used in previous decades due to the new criteria and diagnostic categories proposed by the American Psychiatric Association in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5).2

In addition to cognitive and functional signs characteristic of NDs, there are behavioural disturbances (BD), which also affect patient functioning and may appear at any point in the course of the disease with a highly variable grouping pattern.3 BD are defined as a heterogeneous group of symptoms that impact various domains of an individual's psychic functioning, such as affect, thinking and behaviour.4 BD are common in patients with a diagnosis of ND, whether it is MiND or MaND.5–7

BD negatively impact the patient and his or her carers to a far greater extent than cognitive decline symptoms themselves.5 BD are associated with risk behaviours8, a higher percentage of institutionalisation, more hospitalisations on mental health units9 and greater use and higher costs of health services.10

Despite the importance of BD in the course and follow-up of NDs, the different studies that have examined their prevalence have reported disparate, inconclusive data in the various samples analysed.5–7 Some studies have indicated that BD may be found in any type of ND and in any stage of the disease.11,12 The studies have shown major differences in reporting the prevalence of BD in NDs. Some have found that 59% of patients with MiND may present BD13; others have indicated that 50-80% of patients with ND have BD in the course of their disease.11 Although these reports provide important information on BD in NDs, the prevalence of BD in the different types of ND — including MiND and MaND — has yet to be determined. Regardless of prevalence, the impact of BD on quality of life and care for people with ND renders BD a very important subject in the study of the population with this condition.

The objective of this study was to determine BD frequency and type in a group of patients with a diagnosis of ND (making a distinction between MiND and MaND) assessed at the Intellectus Memory and Cognition Centre at Hospital Universitario San Ignacio [San Ignacio University Hospital] in 2015.

Material and methodsDesignThis was a retrospective, descriptive, observational study.

PopulationA review of 859 medical histories yielded 507 patients with a diagnosis of ND (either MaND or MiND) evaluated at the Intellectus Memory and Cognition Centre at Hospital Universitario San Ignacio in Bogotá, Colombia, between 1 January and 31 December 2015. An interdisciplinary assessment was performed as described below.

Evaluation of the group of cases at the memory clinicGeriatric medicine, psychiatry, neurology and neuropsychology conducted a standardised interdisciplinary assessment. Geriatric medicine performed a full evaluation of the patient's baseline condition that included multimorbidity, functioning and social situation. Psychiatry conducted a semi-structured interview to detect BD according to the classification of the International Psychogeriatric Association (IPA)4 and the DSM-5.2 The interview also ruled out BD that could be attributed to an independent mental illness. The neurology department performed an in-depth examination of the medical history and risk factors for cerebrovascular disease, checked for other nervous system diseases and conducted a neurological examination. The neuropsychology department was responsible for doing a full battery of neuropsychology tests, which included examination of various cognitive domains such as memory, executive function, attention, visuoconstructional function, language and social cognition. Following the assessments mentioned, an interdisciplinary decision-making board was convened to arrive at a diagnosis and consensus recommendations.

Study conductAll medical histories for patients assessed at the Intellectus Memory and Cognition Centre at Hospital Universitario San Ignacio during the period mentioned were taken. Patients with a diagnosis of ND according to the criteria of the DSM-5, which divides NDs into major and mild forms depending on the functional decline caused by the cognitive deficit, were enrolled. The manual includes as part of the diagnosis the presence of BD, which depends on whether the cognitive disorder is accompanied by clinically significant BD.2 Patients who had any concomitant chronic mental illness with a diagnosis of neurocognitive disorder and patients with disorders related to the use of psychoactive substances were excluded.

InstrumentsFunctioning in basic activities of daily living was measured using the Barthel Index, which was initially developed to evaluate the capacity for self-care of people with neuromuscular abnormalities and is now used to screen for dependency in basic activities of daily living. This scale is easy to apply and useful for longitudinal patient follow-up.14

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was used as a general measure of cognition. This test has shown high sensitivity in tracking cognitive functioning in general and is widely supported for initial follow-up of abnormalities in domains such as memory, language, executive function and visuoconstructional capacity in people with NDs.15,16

The Yesavage scale was used to screen for depression. This scale has high internal and external reliability and validity in detecting depression in older adults.17 As the patients in question had a diagnosis of ND, the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia was also used. This 19-item instrument administered to both patients and carers has high sensitivity, internal validity and inter-observer reliability.18

The standardised battery of neuropsychological tests consisted of specific tests for each cognitive domain. Language was evaluated using tests of phonological and semantic fluency, naming and complex verbal comprehension. Attention was assessed using the Symbol Digit Modalities Test. The visuoconstructional domain was evaluated with the Rey Complex Figure Test. Executive function was assessed using interpretation of sayings, graphomotor series and the Institute of Cognitive Neurology (INECO) screening test. Finally, memory was evaluated using the Grober test.

Statistical analysisAn initial univariate analysis examined outliers and sample distribution. This enabled the variables to be adjusted and categorised. Categorical variables were expressed in terms of frequencies and percentages; means ± standard deviation were used to present continuous variables. The data were subsequently analysed with bivariate models to determine the association between dependent and independent variables;2 tests were used for categorical variables and Student's t-test was used for continuous variables. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Data analysis was performed using the program STATA (version 12) for iOS.

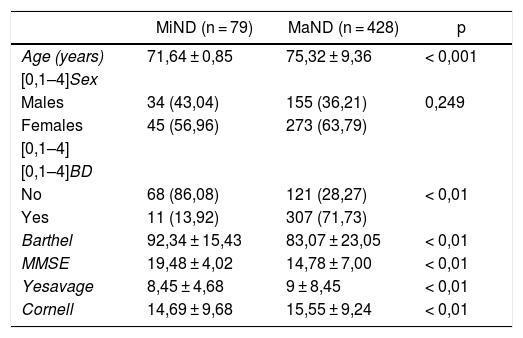

ResultsInitially, 859 medical histories for patients assessed by a memory clinic in 2015 were reviewed. Applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria yielded a total of 507 medical histories with MiND and MaND (Table 1).

Description of the population (n = 507).

| MiND (n = 79) | MaND (n = 428) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71,64 ± 0,85 | 75,32 ± 9,36 | < 0,001 |

| [0,1–4]Sex | |||

| Males | 34 (43,04) | 155 (36,21) | 0,249 |

| Females | 45 (56,96) | 273 (63,79) | |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]BD | |||

| No | 68 (86,08) | 121 (28,27) | < 0,01 |

| Yes | 11 (13,92) | 307 (71,73) | |

| Barthel | 92,34 ± 15,43 | 83,07 ± 23,05 | < 0,01 |

| MMSE | 19,48 ± 4,02 | 14,78 ± 7,00 | < 0,01 |

| Yesavage | 8,45 ± 4,68 | 9 ± 8,45 | < 0,01 |

| Cornell | 14,69 ± 9,68 | 15,55 ± 9,24 | < 0,01 |

BD: behavioural disturbance; MaND: major neurocognitive disorder; MiND: mild neurocognitive disorder: MMSE: Mini-mental State Examination.

Values express n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

The mean age of the people with MiND at diagnosis was 71.04 years, and that of those with MaND was 75.32 years (p < 0.001). There were more women than men with a diagnosis of ND (318 women and 189 men). This difference persisted when the sample was stratified by severity (MiND versus MaND); however, it was not statistically significant (p = 0.249).

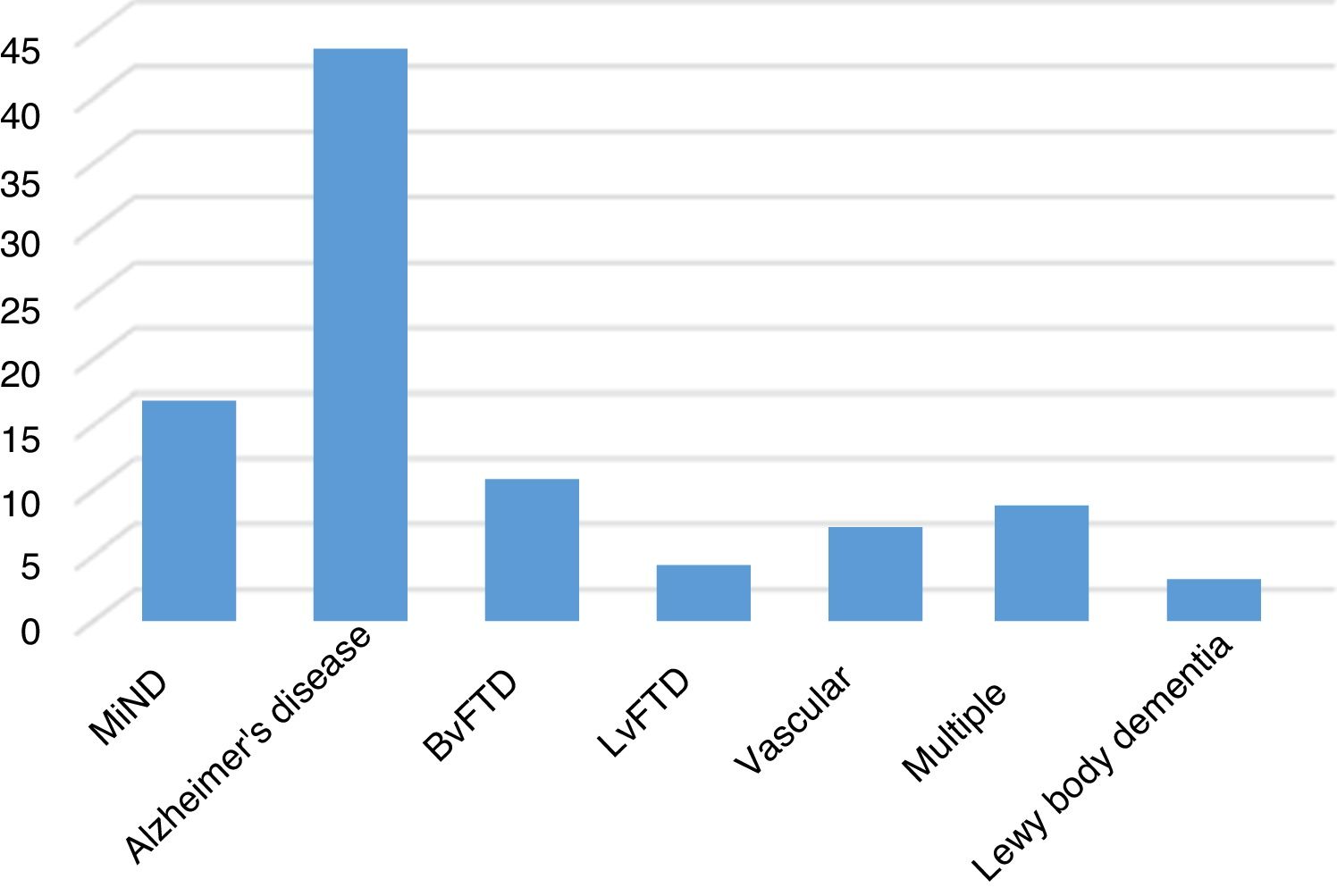

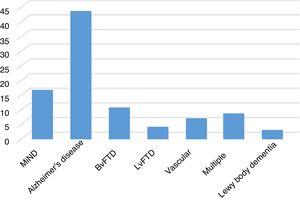

Among aetiologies of ND, Alzheimer's disease was the most common, followed by behavioural variant frontotemporal lobar degeneration (BvFTD), and finally disorders of multiple aetiologies and those of vascular aetiology (Fig. 1).

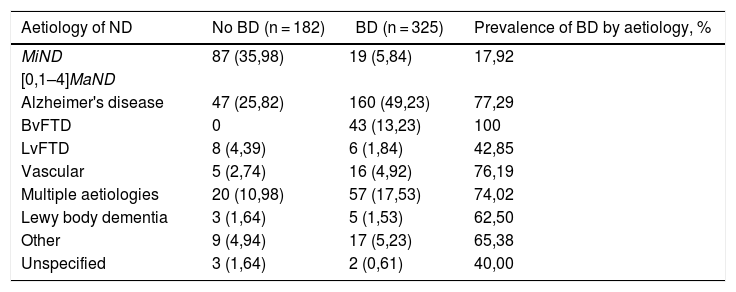

The analyses showed a higher frequency of BD in patients with MaND than in patients with MiND (Table 1). When the group with MaND was analysed, the highest frequency of BD corresponded to BvFTD, followed by Alzheimer's disease, vascular aetiologies and multiple aetiologies (Table 2).

Prevalence of behavioural disturbance by aetiology of neurocognitive disorder.

| Aetiology of ND | No BD (n = 182) | BD (n = 325) | Prevalence of BD by aetiology, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| MiND | 87 (35,98) | 19 (5,84) | 17,92 |

| [0,1–4]MaND | |||

| Alzheimer's disease | 47 (25,82) | 160 (49,23) | 77,29 |

| BvFTD | 0 | 43 (13,23) | 100 |

| LvFTD | 8 (4,39) | 6 (1,84) | 42,85 |

| Vascular | 5 (2,74) | 16 (4,92) | 76,19 |

| Multiple aetiologies | 20 (10,98) | 57 (17,53) | 74,02 |

| Lewy body dementia | 3 (1,64) | 5 (1,53) | 62,50 |

| Other | 9 (4,94) | 17 (5,23) | 65,38 |

| Unspecified | 3 (1,64) | 2 (0,61) | 40,00 |

BD: behavioural disturbances; BvFTD: behavioural variant frontotemporal degeneration; MaND: major neurocognitive disorder; MiND: mild neurocognitive disorder; LvFTD: language variant frontotemporal degeneration.

Unless otherwise indicated, values express n (%).

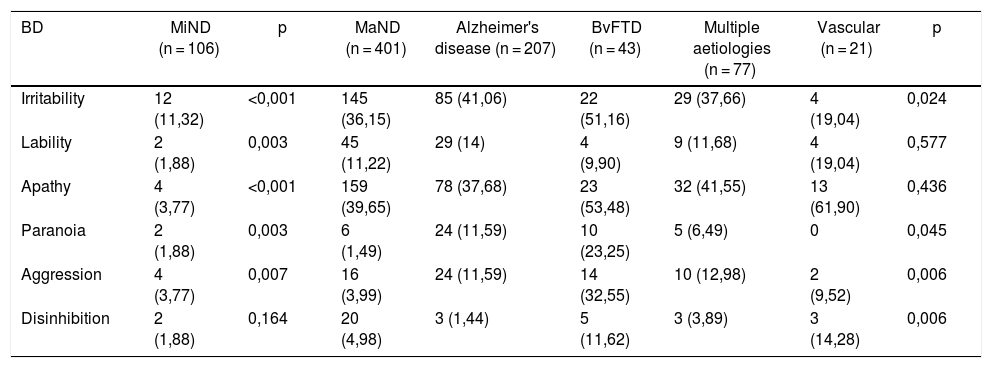

Apathy, irritability, aggression and emotional lability were the most common types of BD, but differences by severity were seen. Subjects with MiND presented more irritability, apathy and aggression; those with MaND presented more apathy, irritability and emotional lability. When BD was analysed by aetiology in subjects with MaND, the following were seen (in order of frequency): in Alzheimer's disease, irritability, apathy, emotional lability, paranoia and aggression; in BvFTD, apathy, irritability and aggression. In subjects with MaND of vascular aetiology, apathy, irritability and emotional lability were most common; and in ND due to multiple aetiologies, apathy, irritability and aggression were most common (Table 3).

Prevalence of most common types of behavioural disturbance by aetiology of neurocognitive disorder.

| BD | MiND (n = 106) | p | MaND (n = 401) | Alzheimer's disease (n = 207) | BvFTD (n = 43) | Multiple aetiologies (n = 77) | Vascular (n = 21) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irritability | 12 (11,32) | <0,001 | 145 (36,15) | 85 (41,06) | 22 (51,16) | 29 (37,66) | 4 (19,04) | 0,024 |

| Lability | 2 (1,88) | 0,003 | 45 (11,22) | 29 (14) | 4 (9,90) | 9 (11,68) | 4 (19,04) | 0,577 |

| Apathy | 4 (3,77) | <0,001 | 159 (39,65) | 78 (37,68) | 23 (53,48) | 32 (41,55) | 13 (61,90) | 0,436 |

| Paranoia | 2 (1,88) | 0,003 | 6 (1,49) | 24 (11,59) | 10 (23,25) | 5 (6,49) | 0 | 0,045 |

| Aggression | 4 (3,77) | 0,007 | 16 (3,99) | 24 (11,59) | 14 (32,55) | 10 (12,98) | 2 (9,52) | 0,006 |

| Disinhibition | 2 (1,88) | 0,164 | 20 (4,98) | 3 (1,44) | 5 (11,62) | 3 (3,89) | 3 (14,28) | 0,006 |

BD: behavioural disturbances; BvFTD: behavioural variant frontotemporal degeneration; MaND: major neurocognitive disorder; MiND: mild neurocognitive disorder.

Values express n (%).

This study examined BD in patients diagnosed with ND (MiND or MaND) in 2015 at a centre specialising in cognition in Bogotá. It found that the most common types of BD were apathy, irritability, aggression and emotional lability and that the least common types were hallucinations, psychosis and sadness.

A high frequency of BD was found in the different aetiologies of ND. This might have been explained by the fact that the interdisciplinary group conducted a systematic evaluation of BD.

At our centre, the highest frequency of BD was seen in subjects with BvFTD, followed by those with Alzheimer's disease, those with disorders of vascular aetiology and, finally, those with disorders due to multiple aetiologies.

In addition, a rate of BD as high as 13.92% was seen in MiND, indicating that BD was significant regardless of ND severity or aetiology. When this study was compared to prior studies, similar prevalences were found.12

Previous studies on BD prevalence in patients diagnosed with MaND have reported depression/dysphoria, apathy, delirium and anxiety/aggression as the most common types of BD in the population.19 Other studies in institutionalised patients diagnosed with MaND have shown a prevalence of BD of up to 92%,20 with the most commonly seen types of BD being apathy, irritability, aberrant motor behaviour and agitation/aggression.21 In our study, in general, the prevalence of BD was similar to that in prior publications, but differed in that emotional lability was more prevalent in our population.

When BD prevalences were compared, studies that had only determined the presence or absence of dementia reported apathy, irritability, persecution and depression; in others, aberrant motor behaviour and aggression were also prevalent.22,23

Moreover, articles that examined BD by aetiology of ND have found a prevalence in Alzheimer's disease of 66–100%; the most commonly reported types of BD were apathy, irritability and depression.24 Others found a prevalence of BD of up to 39%, particularly in the form of aggression, alteration of activity and psychosis.12 In this study, in general, the frequency of BD in MaND due to Alzheimer's disease was similar and only differed in that emotional lability was also common in the population studied.

A study with 60 patients, divided into those with multi-infarct dementia and those with subcortical ischaemic vascular disease, reported a BD prevalence of 95%; types of BD included apathy, abnormal eating behaviour and irritability.25 These results did not differ from our own, which found BD to be present in more than 50% of cases of ND of vascular aetiology in the form of apathy, irritability or emotional lability, although abnormal eating behaviour did not appear.

BD in patients with a diagnosis of MaND contributes to early institutionalisation, a decline in quality of life for both patients and carers, carer overload, increased disability4 and the costs involved in care for patients with dementia.26

BD appear to play a role in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with ND. A group of prior studies indicated that BD in cognitively normal patients may predict cognitive decline.27,28 Thus, criteria for mild behavioural impairment have been proposed as a way to identify early incipient changes associated with neurodegenerative diseases of any aetiology.29

BD in NDs seems to lie at the core of a group of neuropsychiatric disturbances that include changes in cognitive, affective and social interaction processes.29 Furthermore, some types of BD would seem to arise from the decline in the processes described. For example, disinhibited behaviour could be tied to changes in inhibitory control and other executive functions, considering emotional regulation processes. Similarly, affective, cognitive and social changes could be described in symptoms such as apathy and irritability.29 Interactions between these cognitive, affective and social abnormalities, added to BD, are associated with changes in the course of MaNDs.

Therefore, considering that BD are associated with the adverse outcomes reported,4,26 investigation of these abnormalities in NDs opens up an opportunity to investigate how better behaviour management may impact treatment response, follow-up and disease prognosis.

Further studies should evaluate the presence of BD using other standardised instruments. Demographic and cognitive factors associated with changes in BD prevalence in different types of ND must also be examined. Finally, subsequent studies must analyse the extent to which better management of BD could alter the progressive course of the disease.

Limitations of this study include its cross-sectional methodology, which impeded causal inference, and the fact that it was conducted at a leading national specialised centre for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with suspected ND, as it precluded evaluation of BD prevalence in the general population. Another limitation is the way in which BD were evaluated, i.e. by clinical consensus rather than a scale. However, some publications have stated that one source of information on the presence of BD is direct observation by a medical team.4,30

ConclusionsThis study sought to determine the frequency of BD in a group of patients with a diagnosis of ND in the target population. Following evaluation of reports of interdisciplinary assessments by a memory clinic, it can be affirmed that BD is a common manifestation in patients with ND in general, and is prevalent in MiND and in the different aetiologies of MaND according to other studies.

Although BD essentially appears in MaND, it does also present in MiND. This is significant as BD has been proposed as a way to identify early changes associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Identification of BD in our population has valuable implications for developing and implementing specific treatment strategies to decrease its impact on the patient, carer and health system.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Chimbí-Arias C, Santacruz-Escudero JM, Chavarro-Carvajal DA, Samper-Ternent R, Santamaría-García H. Alteraciones del comportamiento de pacientes con diagnóstico de trastorno neurocognoscitivo en Bogotá (Colombia). Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:136–141.

The authors Claudia Chimbí-Arias and José Manuel Santacruz-Escudero have contributed equally to this work.

Study presented at the XII Congreso Colombiano de Gerontología y Geriatría [12th Colombian Gerontology and Geriatrics Conference], Bogotá, Colombia, 21 May 2016.