Depression represents a major disease burden in Colombia. To better understand opportunities to improve access to mental healthcare in Colombia, a research team at Javeriana University conducted formative qualitative research to explore stakeholders’ experiences with the integration of mental healthcare into the primary care system.

MethodsThe research team conducted 16 focus groups and 4 in-depth interviews with patients, providers, health administrators and representatives of community organisations at five primary care clinics in Colombia, and used thematic analysis to study the data.

ResultsThemes were organised into barriers and facilitators at the level of patients, providers, organisations and facilities. Barriers to the treatment of depression included stigma, lack of mental health literacy at the patient and provider level, weak links between care levels, and continued need for mental health prioritization at the national level. Facilitators to the management of depression in primary care included patient support systems, strong patient-provider relationships, the targeting of depression interventions and national depression guidelines.

DiscussionThis study elucidates the barriers to depression care in Colombia, and highlights action items for further integrating depression care into the primary care setting.

La depresión representa una importante carga de enfermedad en Colombia. Para comprender mejor las oportunidades para mejorar el acceso a la atención de la salud mental en Colombia, un equipo de investigación de la Universidad Javeriana realizó una investigación cualitativa formativa para explorar las experiencias de las partes interesadas con la integración de la atención de la salud mental en los servicios de atención primaria.

MétodosEl equipo de investigación realizó 16 grupos focales y 4 entrevistas en profundidad con pacientes, proveedores, administradores de salud y representantes de organizaciones comunitarias en cinco clínicas de atención primaria en Colombia, y utilizó un análisis temático para analizar los datos.

ResultadosLos temas se organizaron en barreras y facilitadores al nivel de pacientes, proveedores, organizaciones y estructuras. Las barreras para el tratamiento de la depresión incluyeron estigma, falta de conocimientos sobre salud mental a nivel del paciente y del proveedor, vínculos débiles entre los niveles de atención y la necesidad continua de priorización de la salud mental a nivel nacional. Los facilitadores para el manejo de la depresión en la atención primaria incluyeron sistemas de apoyo al paciente, relaciones sólidas entre el paciente y el proveedor, la focalización de las intervenciones para la depresión y las guías nacionales de depresión.

DiscusiónEste estudio aclara las barreras para la atención de la depresión en Colombia y destaca los elementos de acción para integrar aún más la atención de la depresión en el entorno de atención primaria.

In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), depression is common, highly burdensome, and results in negative outcomes at the individual and societal level. Among LMICs, depression is ranked as the leading neuropsychiatric cause of the burden of disease.1 This burden is also felt in Colombia, where depressive disorders are the 7th leading cause of disability, and there is a 5.4% lifetime prevalence of depressive disorders.2,3 Despite the fact that depressive disorders are common, many individuals in Colombia experience challenges in accessing mental healthcare. The 2015 National Mental Health Survey in Colombia found that in the past 12 months, less than half of individuals with a mental health disorder received any type of care.3 Barriers to accessing care are largely due to the limited mental health workforce in Colombia; in 2017, there were only 1.84 psychiatrists per 100,000 people.4 Additionally, identification of depression remains challenging, particularly in the primary care setting where physicians detect less than half of patients with major depressive disorder.5 These barriers highlight a need for greater integration of depression care into the primary setting in Colombia.

Recent legislative efforts by the Colombian government indicate that the country is moving forward in prioritizing mental health for the population. In 2013, the Colombian government passed Law 1616, which granted all Colombians the right to mental health.6 This law was bolstered in 2018, with a resolution that prioritized the integration of mental healthcare into primary care.7 In support of the Colombian government’s mental health program, researchers from Javeriana University in Colombia and Dartmouth College in the United States worked to develop a new mental health service delivery model, called the DIADA project (Detection and Integrated Care for Depression and Alcohol Use in Primary Care), which uses digital technology to increase access to and quality of mental health services (see Torrey et al. for a description of this model).8 This research team conducted focus groups and in-depth interviews to better understand barriers and facilitators to integrating screening for depression into the primary care setting in Colombia. Although studies across the globe have attempted to understand these barriers and facilitators, including stigma, providers’ confidence in managing depression, financial burdens, and limited mental health training for primary care providers, to our knowledge, no studies have been conducted in Colombia to understand these factors within the primary care setting.9–11

MethodsStudy proceduresWe recruited participants from the five primary care healthcare sites across Colombia that would later become the scale-up sites for the DIADA project. The healthcare centers included: site 1 (an urban ambulatory healthcare center in Bogotá), site 2 (an urban regional hospital in the state of Boyacá), site 3 (a rural primary care center), site 4 (a rural clinic that provides care to urban and rural populations), and site 5 (a rural clinic that coordinates mental health services for 47 municipalities). Dartmouth College and Javeriana University’s Institutional Review Boards approved this study.

Focus groups and interviews were held with four different types of participants: healthcare professionals, healthcare administrators, patients, and community organization representatives. As part of the inclusion criteria, all participants were at least 18 years old. Healthcare workers were required to have worked in their respective health institution for at least nine months, patients were required to have used the institution’s health services within the last 12 months, and community organization representatives were required to have had more than five years of experience in the community. Participants were compensated the equivalent of US $16 for their participation. All participants signed informed consent.

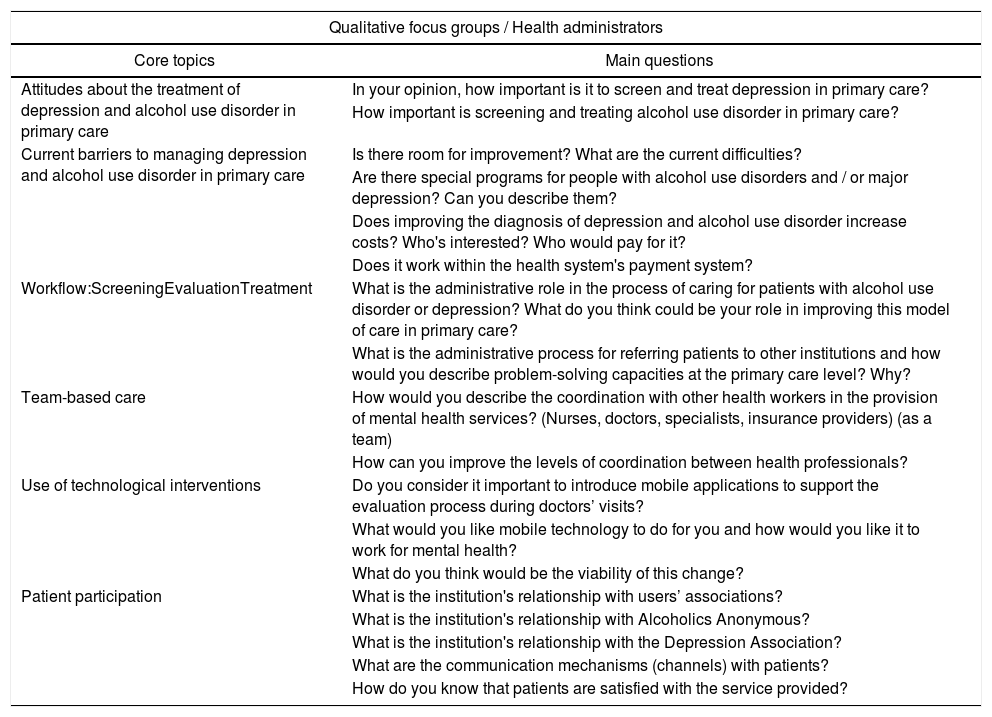

An experienced facilitator, an anthropologist with extensive training in this methodology, led the focus groups, which were grouped by type of participant. To enable a more in-depth understanding of themes identified in the focus groups, the research team recruited participants from previous focus groups to participate in semi-structured in-depth interviews, based on willingness to participate. Two researchers with training in qualitative methods led these hour-long interviews. See Table 1 for example focus group guiding questions.

Focus group example guiding questions.

| Qualitative focus groups / Health administrators | |

|---|---|

| Core topics | Main questions |

| Attitudes about the treatment of depression and alcohol use disorder in primary care | In your opinion, how important is it to screen and treat depression in primary care? |

| How important is screening and treating alcohol use disorder in primary care? | |

| Current barriers to managing depression and alcohol use disorder in primary care | Is there room for improvement? What are the current difficulties? |

| Are there special programs for people with alcohol use disorders and / or major depression? Can you describe them? | |

| Does improving the diagnosis of depression and alcohol use disorder increase costs? Who's interested? Who would pay for it? | |

| Does it work within the health system's payment system? | |

| Workflow:ScreeningEvaluationTreatment | What is the administrative role in the process of caring for patients with alcohol use disorder or depression? What do you think could be your role in improving this model of care in primary care? |

| What is the administrative process for referring patients to other institutions and how would you describe problem-solving capacities at the primary care level? Why? | |

| Team-based care | How would you describe the coordination with other health workers in the provision of mental health services? (Nurses, doctors, specialists, insurance providers) (as a team) |

| How can you improve the levels of coordination between health professionals? | |

| Use of technological interventions | Do you consider it important to introduce mobile applications to support the evaluation process during doctors’ visits? |

| What would you like mobile technology to do for you and how would you like it to work for mental health? | |

| What do you think would be the viability of this change? | |

| Patient participation | What is the institution's relationship with users’ associations? |

| What is the institution's relationship with Alcoholics Anonymous? | |

| What is the institution's relationship with the Depression Association? | |

| What are the communication mechanisms (channels) with patients? | |

| How do you know that patients are satisfied with the service provided? | |

We used audio recorders to record the focus groups and interviews, transcribing the interviews verbatim in Spanish and replacing personally identifiable information with de-identified labels. Subsequently, three experts in qualitative research independently read the transcripts. The authors first performed a deductive analysis of the data, based on a preliminary matrix of categories created by the research team. They then conducted a thematic analysis of the data, using the matrix to guide this analysis. This exploratory methodology allowed them to identify patterns across stakeholder perceptions.12,13 The authors used NVivo 11 software to code and analyze the data.14 All analyses were conducted in Spanish. The authors iteratively identified themes to create their codebook, and open coded one transcript to ensure consistency. The coders also completed a test of inter-coder reliability to resolve coding discrepancies.

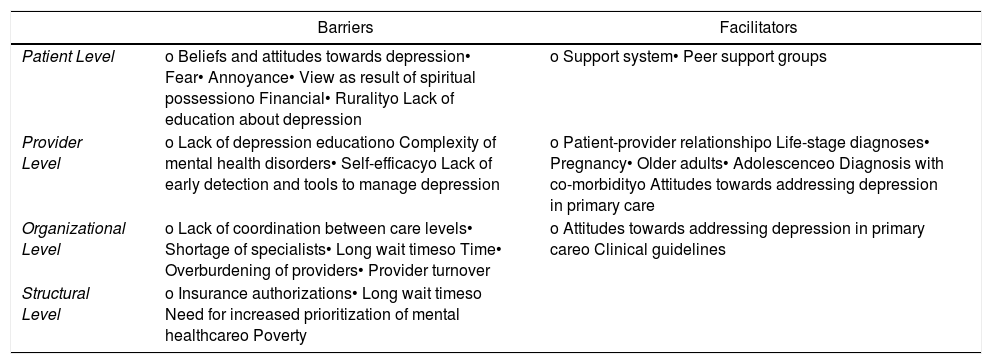

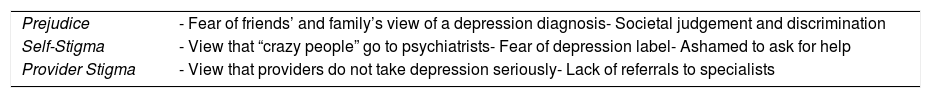

ResultsIn total, 16 focus groups and 4 in-depth interviews were completed across the five sites. The focus groups involved 108 participants, including 36 patients, 30 health professionals, 26 health administrators, and 16 community organization representatives. Interviews were completed with one participant from each group (see Cardenas et al. for participant characteristics). The results are organized, based on Chaudoir et al.’s multi-level framework of factors that impact implementation outcomes, into patient, provider, organizational, and structural level barriers and facilitators to implementation (see Table 2).15,16 They begin by highlighting an overarching barrier to depression management, stigma, which is broken down into social stigma, which we refer to as “prejudice,” self-stigma, and provider stigma, based on Ahmedani’s model of stigma levels (see Table 3).17 Depression stigma is a particularly important barrier to understand, given that a cross-national study of depression stigma in 16 countries found that globally there exists a “backbone of stigma” that requires better understanding to effectively dismantle.18

Barriers and facilitators to addressing depression within the primary care setting.

| Barriers | Facilitators | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Level | o Beliefs and attitudes towards depression• Fear• Annoyance• View as result of spiritual possessiono Financial• Ruralityo Lack of education about depression | o Support system• Peer support groups |

| Provider Level | o Lack of depression educationo Complexity of mental health disorders• Self-efficacyo Lack of early detection and tools to manage depression | o Patient-provider relationshipo Life-stage diagnoses• Pregnancy• Older adults• Adolescenceo Diagnosis with co-morbidityo Attitudes towards addressing depression in primary care |

| Organizational Level | o Lack of coordination between care levels• Shortage of specialists• Long wait timeso Time• Overburdening of providers• Provider turnover | o Attitudes towards addressing depression in primary careo Clinical guidelines |

| Structural Level | o Insurance authorizations• Long wait timeso Need for increased prioritization of mental healthcareo Poverty |

Impact of stigma on depression identification and management.

| Prejudice | - Fear of friends’ and family’s view of a depression diagnosis- Societal judgement and discrimination |

| Self-Stigma | - View that “crazy people” go to psychiatrists- Fear of depression label- Ashamed to ask for help |

| Provider Stigma | - View that providers do not take depression seriously- Lack of referrals to specialists |

The first level within Ahmedani’s model of stigma levels that impacted depression treatment and identification was prejudice. Prejudice is a structural belief in society that individuals with a specific stigmatized condition are part of an inferior group.17 Mental health prejudice can lead to discrimination, be influenced by or further negative stereotypes of individuals with mental illness, and concerningly, has remained steady across time.18,19 One manifestation of prejudice in our interviews was patients’ fear of how their social network would react to their disclosure of their depression. Healthcare administrators felt that many patients did not disclose their depression symptoms to their providers out of fear that this disclosure could cause tension in their family and judgment from society. Additionally, a patient expressed that among her family and friends, a diagnosis of a mental illness was viewed as the worst possible diagnosis that a person could receive. This prejudice encouraged participants to hide their diagnoses to avoid tensions within their social network and discrimination from society.

Self-stigmaThe second level of stigma experienced by our participants that impacted their views of depression and treatment seeking behavior was self-stigma. Self-stigma is the internalization of prejudice by an individual with the stigmatized condition, whereby the impact of societal stigma can lead an individual to feel guilty or inadequate about their illness.17 As described by modified labeling theory, the fear of being labeled as someone with a mental illness can cause a person to feel stigmatized, which in turn can impact their self-esteem, lead them to miss out on work and other important opportunities, and avoid seeking care.20–22 Many providers and health administrators discussed their perceptions of patients’ self-stigmatization and the label of “crazy” that patients placed on diagnoses of mental illness. They described how many patients did not go to the doctor for their depression because they felt that only “crazy people” go to psychiatrists. This self-stigmatization manifested in individuals’ fear of being labeled and connected to a diagnosis of depression. Self-stigmatization also had the effect of causing patients to want to manage their depression on their own, to avoid the stigmatized labels associated with mental illness.

Provider stigmaThe third level of stigma, provider stigma, develops in a similar way to prejudice, whereby mental health professionals may desire to create social distance from individuals with mental health disorders, or may do so unintentionally, resulting in a reduction in early detections and sufficient follow-up.17 Provider stigma has been found to lead to patients feeling labeled or marginalized by health professionals, discontinuing treatment, and avoiding seeking care.23 Although in general, providers in our study expressed support for the treatment of depression in the primary care setting, some patients reported feeling that their providers did not take their mental illness seriously. Some patients reported that after their provider identified their depression, they were only told to manage it the best that they could, and were not given further treatment or referrals.

Patient level barriersBeliefs and attitudes towards depressionOne of the main barriers to seeking depression treatment at the patient level was patients’ beliefs and attitudes towards depression and seeking treatment for depression. The first attitude expressed by patients towards seeking treatment for depression was fear of becoming addicted to psychiatric medications or that medication would not resolve their illness. Providers perceived that these fears led patients to reject their diagnoses and referrals, and that they ultimately did not return to appointments. Another attitude towards depression treatment that patients expressed was annoyance. Providers and administrators commented that some patients expressed annoyance at diagnoses of depression; “in general, mental health diagnoses bother patients a lot, above all older adults, because they believe that one is underestimating their other pathologies, their other things” (Focus Group Site 1 Administrators).

Financial barriersA second barrier for patients in seeking depression treatment, particularly in rural settings, are financial barriers. Although, under Law 100 all Colombians are entitled to a comprehensive health benefits package, and out-of-pocket expenses account for one of the lowest rates of total health expenditures in the region (14.4%), the indirect costs associated with accessing mental healthcare represent a burden to the population.24 In rural settings that lack specialized mental health providers, once a depressive disorder is diagnosed in the primary care setting, patients described having to be referred to providers in neighboring regions. They recounted needing to pay for transportation and a hotel, which represented a major financial barrier. In these cases, patients sometimes were forced to choose between feeding themselves and their family, or travelling to care. Due to these financial barriers, rural patients were frequently lost to follow-up or ended up back in primary care, after having experienced a mental health crisis.

Lack of education about depressionThe third barrier to seeking treatment at the patient level was a lack of patient education about depression and mental illness. Health administrators identified mental health education as a large need in Colombian society, as a means of reducing the stigma surrounding mental illness. They described how the population needs more education around the idea that depression is an illness, which needs to be managed like any physical illness. This lack of mental health education meant that many patients had symptoms of depression, but did not feel prepared to ask their providers for help. Additionally, without education about depression, the friends and family of depressed individual tend to miss their symptoms; this barrier is particularly apparent among older adults, whose family members may just view their depression as a symptom of their old age.

Provider level barriersLack of education managing depressionAt the provider level, the biggest barrier to identifying and managing depression in the primary care setting was a lack of provider training in mental healthcare. Primary care providers, particularly from medical schools outside of Bogotá, reported that they did not get enough, or any, training in medical school in depression diagnosis and management, and felt that they often missed diagnoses or were only able to identify depression in moments of crisis. Even when providers are able to diagnose depression, they often do not feel that they have the tools to manage or do not know about the depression guidelines for treatment and diagnosis. Additionally, providers described how technical guidelines for mental illness were not sufficiently modified for the rural Colombian context, which made it challenging to provide depression care in this setting. Due to this lack of training, providers reported that they sometimes could not educate their patients about depression: “providers were not taught to educate patients…because they do not have time or patience…because many patients leave the appointment and say, ‘I didn’t understand the doctor about how to take the medication’ or ‘the doctor didn’t tell me, and I simply asked a question and he/she is very bad-tempered’” (Focus Group Site 2 Providers).

Because of a lack of depression education, providers reported that there was not enough early detection of cases in primary care, and that patients’ depression often went untreated until it reached a point that required a higher level of care. Providers and administrators reported that many of the cases that are detected come from the emergency department, and that providers sometimes do not follow-up with patients with depression until they have had a suicide attempt.

Complexity of mental health disordersProviders also identified the complexity of mental illness as a barrier to recognition. Multiple providers reported that it was harder to identify mental than physical illness as they oftentimes come with co-morbidities and are less “quantifiable” than physical illnesses. They described how with mental illness; they frequently treat the symptoms of the illness rather than the illness itself. The combination of insufficient training and the difficulty of identifying when a patient was experiencing a mental health disorder reduced primary care providers’ self-efficacy for addressing depression.

Organizational level barriersLack of coordination between care levelsThe main barrier to treating depression at the organizational level was a lack of strength of the referral network between primary and secondary care, and a lack of resources for treating depression at the specialist level. Providers and health administrators reported that there were not enough psychiatrists and psychologists nearby to whom they could refer depression cases. Because there were so few specialists, patients reported that they experience long wait times for appointments and are often treated only with medication. Consequently, they reported removing themselves from the waitlist before their appointment, which meant that they were returning to the primary care system for treatment. Providers also expressed that patients are frequently lost to follow-up when there are no specialists nearby to treat them. One hospital administrator stated, “In this moment we are attending crisis episodes, but if we identify them early…I need to have a site where I am going to provide care for them and focus, so this means that I need to have medications, people’s availability, and a physical payment infrastructure…I do not have psychiatrists or psychologists prepared in this theme [depression] and there is so much rotation of personnel, what am I going to do with this patient…better that we do not identify it [depression]” (Focus Group Site 2 Health Administrators).

TimeProviders at the primary care level also reported feeling overburdened due to a lack of time in their appointments. They described how especially with patients with comorbidities, these patients’ physical concerns were generally their primary reason for their appointment, and that it was difficult to manage their depression while trying to resolve their physical health concern. They also addressed how a high rotation of providers within the primary care setting led to an overburdening of providers, and that these organizational barriers meant that it was difficult to provide continuous care.

Structural level barriersInsurance authorizationsAt the structural level, insurance authorizations, specifically authorizations for referrals to secondary levels of care or for specific medications, represented a barrier to depression care. Patients and health administrators reported that because insurance medication providers are sometimes unsystematic, it could take months to obtain insurance authorizations from the public insurance system, which was difficult for depressed patients who require frequent visits and continuity of care. Patients stated that they sometimes get their medication authorizations in one town, but need to travel to another to fill them, which is an arduous process.

Need for increased priority of mental health careA second structural barrier that patients and providers identified was the politicization of health. Although the Colombian government has in many ways made mental health, and the delivery of mental health a priority, some providers still felt as though there needed to be more action from the government and medical schools to complete this integration. Some providers felt that there were politicians who did not view mental health as cost-effective in the short term, which meant that they delayed making it a political priority.

PovertyFinally, providers and administrators reported that poverty was an important structural barrier to providing high quality depression care. They described how they have found that some of their patients’ depression was caused or made worse by their lack of resources and daily struggles. One provider reported that in these cases, he was unsure how to successfully treat his patients’ depression without also addressing their social environment, and that it was almost impossible to comply with international guidelines for depression care.

Patient level facilitatorsSupport networksThe main patient level facilitator to depression management that our participants described was support networks. Patients and providers noticed that individuals who asked for help for their depression were those who had a strong support system. They shared that these patients had often already accepted their diagnosis, with the help of their friends and family, and were looking for tools to address their depression. Patients also described how one way that they would like to increase their support networks would be through depression peer support groups. One patient mentioned that “I’m more interested in a group where one can share and have ties and belonging than to go a psychiatrist and take pills” (Focus Group Site 1 Patients).

Provider level facilitatorsPatient-provider relationshipThe first provider level facilitator identified by participants was a strong two-way patient-provider relationship. Patients stated that it is important for providers to converse with their patients about their illness to improve their understanding of their condition and medications. Providers felt that some patients are able to express their depression easier than others, which is why taking the time to develop rapport is essential in depression identification. Additionally, providers stressed that the strength of mental health stigma is why the patient-provider relationship is so important. One doctor expressed, “If they do not understand their problem, they are not going to accept opportunities for treatment for alcoholism and depression because they are going to feel mentally ill. You do not want to make it an additional burden for them. So, you have to change it into an opportunity…when they understand, then they act on recommendations, but you have to cultivate this relationship” (Focus Group Site 1 Providers).

Life stage diagnoses and comorbiditiesA second facilitator of depression diagnosis at the provider level was promoting depression care at stages in patients’ lives. Providers discussed how because depression emerges more frequently at particular life stages, they can screen for depression during this time, and potentially identify the disease early. Depression “is a disorder that one sees repeated in different life cycles, from little kids to very old adults. And it can be triggered by anything, in a child there are many factors, in an adolescent, in an adult…” (Focus Group Site 1 Providers).

Specifically, some of the study participants from a lactating mothers’ group described how during pregnancy and post-pregnancy, Colombian providers are more willing to diagnose their patients with depression and refer them to psychologists. Because gynecologists complete a psychosocial risk scale with their pregnant patients as a form of universal screening, they are more frequently able to identify depression in this group than in the general population. Providers discussed how older adulthood is another stage that should be targeted for depression interventions, as older adults often become depressed due to feelings of isolation, and are more likely to seek care for their depression because it provides them with an opportunity for social interactions. Consequently, providers discussed how older adults should be educated about identifying symptoms of depression, so that they will consult before they experience an adverse event. Providers identified adolescence as a third stage in the life cycle when individuals experience high levels of depression, due to factors like family violence, grades, and relationships. Finally, providers described how community and school-based education about depression symptoms represent opportunities for early identification.

Attitudes towards integrationA facilitator at both the provider and organizational level to depression management was the attitude, shared by both providers and administrators, that it is important to treat depression early, and at the primary care level, where doctors have the greatest access to undiagnosed cases of depression. This desire to make depression screening and treatment within the primary care system a priority signifies that there is significant buy-in for integration.

Organizational level facilitatorsClinical guidelinesA final facilitator of depression management in primary care at the organizational level were the clinical guidelines and protocol for depression treatment. Providers described how particularly in the primary care setting, where there is a high rotation of personnel, the systematic use of depression guidelines was important to provide instructions and stability within the clinic. One doctor described how in depression care, he follows some protocols 100 % of the time, and others he adapts based on his needs in the situation. Overall providers felt that the integration of guidelines within the clinics greatly facilitated depression management.

DiscussionThe goal of this paper was to highlight the barriers and facilitators to integrating depression screening and treatment into the primary care setting in Colombia to inform the implementation of a new model of depression care. There are four action items that arose from this study. First, at the patient level, there is a need to increase mental health literacy. A lack of mental health literacy exacerbated self-stigma and prejudice, which further reduced the likelihood that depressed individuals would seek care. Previous studies have found significant associations between self-stigma, mental health literacy, and openness to seeking professional care.25,26 Research has shown that mental health literacy interventions can reduce mental health stigma and increase mental health treatment seeking.27,28 Furthermore, patients highlighted the importance of their social support networks in deciding to seek care, demonstrating the need for mental health literacy education for patients’ support system. Mental health literacy interventions have the potential to increase the likelihood that individuals will encourage their friends or family to seek help for their mental health disorders.28

Second, we recommend action taken at the provider level to allocate resources towards increased training and tools for primary care providers in depression management. Many providers in our study reported that they had not received enough mental health education, which led them to miss or poorly describe depression diagnoses. However, this barrier also represents an opportunity for increased identification and management of depression; if doctors can target patients at different points in their life when they may be particularly susceptible to depression, then they may be able to reduce self-stigma and increase depression diagnoses. Studies show that in LMICs, trainings targeted to teach primary care providers about depression identification and treatment can improve patients’ depression outcomes.1 In Colombia, a study that trained healthcare professionals in depression management found a statistically significant increase in depression and mixed anxiety-depressive disorder diagnoses, from 5.9% before to 10.6% after the intervention.29

Third, at the organizational level, the biggest theme that emerged was to fortify the linkages between primary and secondary care to improve patients’ continuity of care. Studies have found that at the clinical level, strategies for increasing service linkages in mental healthcare include “partnership forming activities,” such as the development of partnered service arrangements, regular clinical meetings and information sharing, the designation of care managers, and tele-health consultations by psychiatrists to patients in rural clinics.30 At the organizational level, collaborative care models have significantly improved depression outcomes.31

Fourth, at the structural level, the Colombian government has increasingly made the integration of mental health into the primary care setting, a priority. To optimize this political opportunity, greater collaboration between researchers, policymakers, and health worker could facilitate and encourage continued investment in this area. Peru offers an impressive model of mental health reform and prioritization with their creation of Community Mental Health Centers and Guiding Principles for Action in Mental Health.32 Cross-regional knowledge sharing is another important strategy to improve depression screening and treatment in primary care.

The first limitation of this study was that participants self-selected to participate, which could indicate that they had stronger feelings about the integration of depression into the primary care system than the general population. The second limitation was that focus groups and interviews were held in hospitals that had already agreed to be part of the DIADA project. As a result, these hospitals might not have been a representative sample of primary care hospitals and primary care hospital staff’s perceptions of depression in Colombia. However, to capture a broader range of barriers and facilitators, we selected hospitals from multiple regions in Colombia, with settings that ranged from urban to rural.

ConclusionAlthough the barriers described above represent real challenges to depression treatment in Colombia, these results highlighted multiple opportunities for, and already existing facilitators of, depression identification and management in the primary care setting in Colombia. These identified factors directly impacted the integration of the DIADA project’s model of care, specifically in relation to provider and patient depression education, tool creation for depression diagnosis and management, fortifying referral networks for depression, and collaborating with policymakers in Colombia and practitioners in Peru and Chile.8 Finally, these results can inform future depression interventions in Colombia, and in other LMICs that struggle from a paucity of mental health resources and providers, to improve depression outcomes and increase patient ownership of their care.

FundingResearch reported in this publication was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number 1U19MH109988 (Multiple Principal Investigators: Lisa A. Marsch, Ph.D. and Carlos Gómez-Restrepo, MD). The contents are solely the opinion of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH or the United States Government.

Conflict of interestDr. Lisa Marsch, one of the principal investigators on this project, is affiliated with the business that developed the mobile intervention platform that is being used in this research. This relationship is extensively managed by Dr. Marsch and her academic institution.

Dr. Diana Goretty Oviedo-Manrique played an essential goal in developing the interview guides and conducting the interviews that are reported on in this article.

Please cite this article as: Bartels SM, Cardenas P, Uribe-Restrepo JM, Cubillos L, Torrey WC, Castro SM, et al. Barreras y facilitadores para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la depresión en atención primaria en Colombia: Perspectivas de los proveedores, administradores de atención médica, pacientes y representantes de la comunidad. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:64–72.