The aim of this study was to evaluate the auditory hallucinatory experience in a clinical sample of patients with psychiatric symptoms (e.g. Schizophrenia), a religious group (e.g. Christians) and a “control” group (with no mental disorder and non-religious). The sample consisted of individuals of both sexes. The patient sample was recruited in two psychiatric hospitals of Buenos Aires City, the religious from an evangelical cult, and people with no religious beliefs or previous psychiatric symptoms (control group). The Hallucinatory Experiences Questionnaire and the Oxford-Liverpool Inventory Feelings and Experiences were the measurement tools used. The White Christmas Test was also administered in order to assess the degree of vivid imagery hearing based on a version of signal detection paradigm in which the subjects think that they hear a song in the background of white noise. The results showed that patients showed greater attributional bias (compared with evangelicals and the control group), but the religious group also tended to show greater bias (although less) than the control group. In addition, patients tended to show greater schizotypal and hallucinatory experiences compared with the evangelicals and the control group, but surprisingly, the control group showed higher negative schizotypy than the religious group, which indicates that religious practices could help reduce the negative effects of schizotypy.

El objetivo de este estudio es evaluar la experiencia alucinatoria auditiva en una muestra clínica de pacientes con historial psiquiátrico (p. ej., esquizofrénicos), practicantes religiosos (p. ej., cristianos evangélicos devotos) y un grupo control (sin trastorno mental y no religiosos devotos). La muestra estuvo integrada por individuos de ambos sexos. La muestra de pacientes se reclutó en 2 hospitales psiquiátricos de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, un grupo de practicantes religiosos (cristianos devotos) en un culto evangélico y un grupo de control no religioso y carente de síntomas psiquiátricos previos. Se aplicó el Cuestionario de Experiencias Alucinatorias y el Oxford-Liverpool Inventory Feelings and Experiences, y luego se administró el White Christmas Test, que evalúa el grado de la imaginería auditiva vívida con base en una versión del paradigma de detección de señal, en que el sujeto cree escuchar un tema musical en el trasfondo de un ruido blanco. Los pacientes mostraron mayor sesgo atribucional que los evangélicos y el grupo control, pero además los religiosos tambien tendieron a mostrar mayor sesgo (aunque en menor grado) que el grupo control. Además, los pacientes tendieron a mostrar más esquizotipia y experiencias alucinatorias que los evangélicos y el grupo control, pero sorprendentemente el grupo control mostró mayor esquizotipia negativa que el grupo religioso, lo cual indica que las prácticas religiosas podrían contribuir a disminuir los efectos negativos de la esquizotipia.

Hallucinations are known not only to occur in individuals with disorders, as dysfunctional perceptual experiences, but also in the general population. There are cases where people who have no disorder experience a kind of hallucination, for example, a mystical-type one. Most people assume that everyone has the ability to discriminate between thoughts and images, or the things we see and hear. However, we do not know a priori if the perceived events are internal and generated in our mind or external and generated by other agents apart from the person.1 The process of discriminating between these two types of events is known as source monitoring and was studied by Johnson et al. in a series of experiments with a non-clinical population.2 The work of these authors, which focused on the source of memories, shows that we use a variety of clues when we discriminate between the memory of thoughts and the memory of real events.3

For example, contextual time information and spatial location can help a person determine whether or not an event “really happened”, as can the sensory qualities of the memory, the vividness and the detail and complexity. In addition, people can make use of the memories of certain cognitive operations. For example, a person is more likely to recognise an evoked event as a self-generated idea if he/she can remember the cognitive effort involved in generating the idea. If a person remembers performing an act that goes against natural laws or conflicts with what he/she knows about the world, he/she will realise that what he/she remembers is probably a fantasy.1

If judgements in source monitoring are influenced by the inherent possibility of perceiving events, this explains the role of culture in the “shaping” of hallucinatory experiences. It is more likely that an individual whose environment accepts the existence of ghosts or values spiritual experiences will attribute reality to the image of a deceased relative, than another individual whose world is more materialistic and scientific. The impact of external stimuli on hallucinations can also be understood in terms of the source monitoring hypothesis. The ability to locate sounds was assessed using a type of test in which the participants, surrounded by screens, were asked to state the location of the experimenter's voice. Patients with reactive schizophrenia who suffered from hallucinations had poorer skills in locating sounds in space than the control patients.1,4

Morrison et al.5 argued that monitoring abnormalities in patients suffering from hallucinations could probably be better detected if source attributions were measured immediately, rather than measuring the attributions based on memories of the previously presented information. It was possible to achieve this using the methodology proposed by signal detection theory (SDT). SDT is a mathematical theory of perception that proposes that the detection of the external stimulus (or signal) is a function that depends on two factors; the first, perceptual sensitivity, which refers to the effectiveness of perceptual systems; the second, the partiality of the response, which refers to the individual criterion to decide whether a perceived event is a real stimulus or an internal noise. SDT proposes several methods to independently measure sensitivity and bias involving a series of tests in which an individual gives a value to a signal in a noisy background. The assessment value in these circumstances can be divided into four categories: correct (the signal is correctly detected); errors (the signal is present, but it is judged to be absent); correct rejections, and false alarms (the signal is judged to be present when it is not).6

The hallucinatory experience varies greatly across all cultures.7,8 In most Western cultures, hallucinations tend to be considered a threat, whereas in non-Western cultures hallucinations can be considered to be holy experiences.9 This distinction is the difference between psychological and religious interpretations.10 While psychological literature considers hallucinations to be pathological afflictions, religious literature considers some hallucinatory experiences as holy or transcendental (although other experiences may be the opposite, such as demonic possession, for example).11

In keeping with the cognitive approach to hallucinations in terms of attributions and beliefs, other authors have highlighted the importance of studying the subjective experience of hearing voices instead of simply their frequency or content.12 For example, Chadwick et al.13 found in schizophrenic patients that voices perceived as malevolent provoked negative emotions, while voices perceived as benevolent provoked positive emotions. Beliefs about voices were not always linked to the content of voices (in 31% of cases, beliefs were incongruent with content) and were based more on the identity and meaning of the voices. Close et al.14 found that beliefs about malevolence/benevolence were always related to the content of the voice in schizophrenic patients. Although investigation of hallucinations with psychotic patients can have positive effects,15 the typical psychotic perception of the voices is malevolence and the typical reaction, of negative affect and anguish.16

The picture is less clear with regard to studies on religious people. On the one hand, some studies have found many similarities between psychotic and mystical states in delusions and hallucinations. For example, Jackson17 found no clear differentiation between psychotic and spiritual experiences. On the other hand, however, there seem to be differences in the meaning and interpretation attributed to psychotic experiences compared to spiritual experiences and also in the emotional and behavioural reactions to such experiences. Spiritual experiences can have adaptive consequences and improve life, while psychotic experiences lead to negative social consequences and behaviour.18

Peters et al.19 found evidence to support that view in their study. They found that individuals belonging to sects or new religious movements (Druids or Hare Krishna) scored significantly higher in the incidence of delusional ideation than control groups (non-religious and Christian), but they did not differ significantly from psychotic patients. However, these same religious people showed significantly lower levels of distress associated with their delirium than outpatient psychotic patients, with their levels being closer to those of the control group.

Up to now, comparative research on psychotic, religious and “normal” samples related to psychosis and schizotypy has mainly been carried out with reference to delusional beliefs. This study aims to examine the more specific experience of auditory hallucinations in terms of vulnerability to psychosis and religiousness. Compared to “normal” controls, it was expected that psychotic individuals would perceive hallucinations as more negative because the typical psychotic auditory hallucination involves malevolent voices.13,14 However, it was expected that religious people, specifically evangelical Christians, would experience hallucinations as more positive than the controls, because the typical evangelical experience of an auditory hallucination is interpreted in benign terms, even as divine intervention.17,20

White Christmas TestThe vividness of the mental images refers to the quality of the images that a person can or cannot form in response to inductive verbal stimuli. Marks21 defines vividness in terms of being “clear and vivid”. An image will have greater vividness the more it resembles an actual perception in different characteristics such as its brightness or sharpness and how strong or dynamic it is. One way to measure the quasi-perceptual conscious experience in which a mental image is formed is by analysing how an individual verbalises about that subjective experience.22–24

Some studies seem to suggest a relationship between the intensity of the imagery (visual or auditory) and the hallucinatory experience, and propose that the hallucinations may be the result of abnormal vivid mental imagery.25 A theory also developed by Mintz et al.26 argues that hallucinations occur as a consequence of defective reality testing. Horowitz27 proposed that people who hallucinate suffer from a deficit of imagery and produce vivid images from an external source. In an attempt to test this theory, several different types of tests were used to compare psychiatric patients “with” and “without” hallucinations, but the results were contradictory.28,29 Mintz et al.26 used the White Christmas Test (WCT) by Barber et al.,30 and found differences between “hallucinators” and “non-hallucinators”, but it is not clear whether this was the result of differences in imagery or, for example, caused by suggestibility.

In the literature on the experimental psychopathology of hallucinations, the WCT by Barber et al.1,30 is often cited. It is an experimental test that enables artificial hallucinations to be obtained.30,31 The WCT was designed to assess vivid imagery and participants were asked to close their eyes and imagine the song “White Christmas” by Bing Crosby. After 30s, they were asked to rate the strength of their imagery. In the WCT, the subjects are told that this tune has been recorded in the background of some white noise (a soft hissing similar to the static from the radio when needing tuned), but in fact there is nothing in the background. The participants are asked to close their eyes and try to hear the tune. After a certain time, the listening is interrupted and they are asked to rate the quality of what they heard from “not clear at all” to “clear”.

With this test, it was found that a considerable number of participants indicated that they had heard the song, although most also said they did not believe that the song was recorded on the tape. Compared to a control group of healthy individuals, the psychiatric patients who suffered from hallucinations not only claimed to have heard the song when they were under the stimulus of the white noise, but were firmly convinced that the song was really recorded on the tape. As a result, it was concluded that some mental imagery is necessary in individuals, although it is not a necessary condition for genuine hallucinations to occur. Only the combination of two factors, a strong mental imagery and limited reality testing capabilities, produce pathological hallucinations. Barber et al.30 found that approximately 5% of the sample of healthy individuals said they had heard the tune (replicated by other researchers32,33) in a background of white noise.

In that study, the subjects received instructions to close their eyes and imagine that they could hear the famous Bing Crosby song. After 30s, they were asked to rate the intensity of their imagery of the song “White Christmas”. Curiously, more than half of the subjects stated that they clearly heard the tune (p. 16). While Barber et al.30 interpreted this result as evidence of the ease with which the non-clinical population ends up accepting the suggested hallucinations, subsequent studies used the WCT as a paradigm to examine the broader category of normal and abnormal hallucinatory experiences.

Barber et al.30 found that the vast majority of patients who hallucinated (85%) “heard” the tune during the test. However, a minority (40%) of control patients also heard it. The authors concluded that auditory imagery is a necessary condition, but not sufficient for pathological hallucinations to occur, and argued that only in combination with defective reality testing would the vividness of the imagery produce hallucinations.

Using more sophisticated designs (e.g. series of tests with signals and/or noise) than the WCT, some studies have questioned the contribution of vivid auditory imagery in the hallucinatory experience. For example, Bentall et al.4 argue that, if people with hallucinatory experiences have unusual imagery vividness, they would be expected to perform poorly in a task of detecting an auditory signal because of their poor sensitivity to external signals. However, that was not what was found; instead of having reduced perceptual sensitivity, people who scored high on the Launay-Slade Hallucination Scale34 and patients with schizophrenia who had hallucinations showed greater predisposition to believe that an auditory signal was present (i.e., a biased assessment), compared to control participants. This led Bentall1 to believe that “those who hallucinate make quick judgements and rely too much on the nature of their perceptions”.

The crucial point of the WCT is that some people tend to have auditory events when they are directed, but in reality they never actually have them. Because patients who hallucinate and normal participants score high on the Launay-Slade Hallucination Scale and tend to report vivid auditory images in the WCT, the relevance of this phenomenon to clinical and non-clinical hallucinators is taken for granted.26,31 While it is true that previous studies31 have ruled out the possibility that the hallucinatory experience during the WCT is related to hypnotic suggestion, it could well be that such reports have nothing to do with the predisposition to hallucinations, but rather they reflect greater sensitivity to satisfy the expectations of the experimenter (i.e., greater social desirability).

However, hallucination during the WCT could also reflect the general tendency to endorse strange or bizarre topics, a tendency that is typical of people prone to fantasy.35 Propensity to fantasy means a deep and intense involvement in fantasies and imagination.36 Although it is not an inherently pathological trait, people who score high on this trait are susceptible to false memories and show a positive response bias in questionnaires that ask for trivial but detailed autobiographical events,36 tend to have paranormal experiences37 and are good at stimulating dissociative amnesia.36

There are several versions of the WCT. In early studies26,30 participants were instructed to close their eyes and imagine that they heard the tune “White Christmas”. They were then asked if they had had convincing imagery of the song. Apart from the fact that this version seeks to generate hallucinations, it is a short-term memory exercise rather than an auditory perception task. This study is therefore based on a more neutral version which is similar to the signal-detection model.4 People were told that they might be able to hear the tune “White Christmas” and to indicate to what extent they thought they could hear it. More specifically, the participants were taken to a room in the laboratory with acoustic insulation. As they entered the room, the song “White Christmas” by Bing Crosby was playing and they were asked if they were familiar with it. They were then told that they were going to listen to a tape with white noise through their headphones for 3min. They were also told, “The song “White Christmas” you just heard may be mixed in with the white noise. If you think or believe you hear the song clearly, please press the button in front of you. Of course, you can press the button several times if you think you have heard fragments of the song”.

As “White Christmas” was not actually played during the 3min of white noise, the frequency with which the participants pressed the button was assessed. After that period, they were asked to complete a scale about the degree of confidence with which they had actually heard the song (0=I did not hear the song at all; 100=I heard the song loud and clear). In a recent version of Merckelbach et al.,36 a second part is added to the WCT, similar to the signal-detection model. The subjects listen to a fragment of the song before starting the new second part, and they are then told that through headphones they will hear white noise in which fragments of the tune have been inserted. Subjects should press a button when they think they can hear one of these fragments. In the first part of the task, the subject is asked to imagine the melody of the song for 30s and then on a scale of 0–10 (where 0 corresponds to “I didn’t hear anything” and 10 to “the melody seemed very clear”) rate the intensity with which they had imagined the song. All the subjects then listen to the tune equally in order to establish a baseline. While the song is playing, they are given the instructions for the second part of the task, identical to that applied by Merckelbach et al. The subject then listens to the white noise through the headphones for 3min and has to press the space bar on the keyboard every time they think they hear a fragment of the song, while the programme records each participant's frequency of response. At the end, they are asked to indicate the clarity, volume and duration of the fragments they have heard on a scale of 0–10. They are also asked where the music they heard came from, as the individual may attribute it to an external source (they think they heard it outside their head) or an internal source (they think they generated the tune themselves).33

In response to the above, our aim was to try to explain the auditory hallucinatory experience and, to guide us in our research, we devised the following questions: What is the aetiology of auditory experiences in religious groups? To what extent do patients with schizophrenia and devout Christians experience attributional biases in response to an indeterminate stimulus? The general aim of this study was to evaluate the auditory hallucinatory experience in a clinical sample of patients with a psychiatric history (e.g. schizophrenia), a group of religious people (e.g. devout evangelical Christians) and a control group (with no mental illness and non-religious). We hypothesised that: (H1) patients with schizophrenia would score high in the WCT compared to the evangelicals and the control group; (H2) patients with schizophrenia would score high in schizotypy and hallucination compared to the evangelicals and the control group; and (H3) the evangelical group would score high in the WCT, schizotypy and hallucination compared to the control group.

MethodsParticipantsThree mixed-gender groups were formed (each with eight males and eight females) selected by gender and age, similar to the psychiatric patients (religious people and controls). The patients were aged 18–55 (mean 36.06±9.56 years); the devout Christians, 24–70 (44.13±14.40 years); and the control group, 20–71 (30.50±7.82 years). Male patients were recruited at Hospital Nacional J.T. Borda and female patients at Hospital Nacional B. Moyano in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires. All the outpatients were in optimal condition cognitively to respond to the self-administered questionnaires and score the WCT. The devout Christians were members of the Evangelical Christian congregation “Dios Hace Milagros” [God makes miracles], most of whom had lived in the community of the city of Quilmes, in the suburbs of Buenos Aires, for at least five years. The control group was selected from among friends and family members, university colleagues and professionals in general with a good intellectual level, with the inclusion criteria that they were not religious devotees (although all were non-practicing Catholics) and had no psychiatric history.

ProcedureBoth instruments (CEA and O-LIFE) were delivered by hand in a sealed envelope and instructions were given on how to complete them. In the case of patients with schizophrenia, each patient signed an informed consent form, and whoever applied them also wrote down the verbal responses given and/or the reactions to the WCT. The data was treated with confidentiality, and the anonymity of their responses maintained. The WCT and the two instruments were applied individually to each participant.

InstrumentsWhite Christmas TestThe White Christmas test is an experimental test created by Barber et al.30,31 which assesses vivid auditory imagery. The procedure consisted of the following steps: a portable MP3 player was used with a stereo headset that completely covered both ears. The participants were asked to close their eyes while the music was playing. Barber et al. used the 1942 Bing Crosby version of the song “White Christmas”, but for cultural reasons it was decided to replace that with Symphony No. 9 in D minor (Opus 125), composed by the German musician Ludwig van Beethoven (known as “Ode to Joy”). Once they had listened to the tune for 60s, each participant was immediately asked to listen to white noise (a soft hissing similar to the static from the radio when needing tuned) and informed that the same tune could be heard in the background, but nothing had actually been recorded. After another 60s of listening to the white noise, they were asked to indicate the strength of the imagery by rating how clearly they could hear the tune on a Likert scale from “I didn’t hear anything” (0) to “I heard it very clearly” (4) in answer to the question, “How clearly did you hear the tune “Ode to Joy”?”

Cuestionario de Experiencias Alucinatorias (CEA) [Hallucinatory Experiences Questionnaire]38Inspired by the questionnaires created by Barrett,34,39,40 the version used in this study measures the propensity to hallucinate in six sensory modalities identified in 38 items. The CEA includes the auditory, visual, gustatory, tactile, olfactory and hypnagogic/hypnopompic (HG/HP) modalities. The H/H is a subscale that represents the sum of the items corresponding to each sensory modality, but does not distinguish between hypnagogic (while falling asleep) and hypnopompic (waking up). Each item is answered by a five-point Likert scale, from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). The scale's internal consistency is high and the estimated reliability for the subscales was also high (Cronbach's α=0.75).

Oxford-liverpool inventory of feelings and experiences (O-LIFE)40,41The O-LIFE is a self-applied 40-item questionnaire with dichotomous options (yes/no) which can be applied to adolescents and adults, both in the healthy population and the patient population. The O-LIFE assesses four subscales:

- 1.

Unusual experiences (UE)

- 2.

Cognitive disorganisation (CD)

- 3.

Introvertive anhedonia (IA)

- 4.

Impulsive nonconformity (IN)

These subscales also have a high degree of internal consistency. A combination of the four subscales makes it possible to assess two types or “factors” of schizotypy, and provides a total score (α=0.90), derived from the sum of the gross scores of the subscales: unusual experiences/cognitive disorganisation (positive schizotypy) and introvertive anhedonia/impulsive nonconformity (negative schizotypy). O-LIFE contains two dimensions of schizotypy: (a) positive dimension, known as unconventional/abnormal perceptual or cognitive-perceptual experiences, which refers to excessive or distorted functioning of a normal process and includes various forms of hallucinations, paranoid ideation, ideas of reference and thought disorders; and (b) negative dimension, known as anhedonia or interpersonal deficit, which refers to a decrease or deficit in normal behaviour in an individual who has difficulty in feeling pleasure at a physical and social level, affective flattening, lack of any close confidants and difficulties with interpersonal relationships.

ResultsA Shapiro–Wilk analysis was carried out as a hypothesis test on the normality of the variables. From the values obtained, we decided to use ANOVA for the statistical analyses, to compare the scores between religious people, patients and controls in WCT, schizotypy and hallucination.

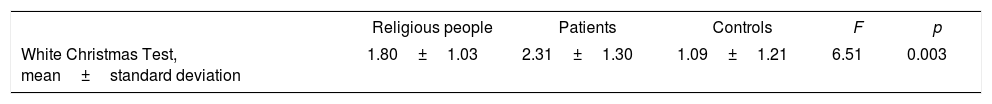

H1 was that patients would score high in the WCT compared to the evangelicals and the control group, which was confirmed — F(2.31)=6.51 (p=0.003) — (Table 1).

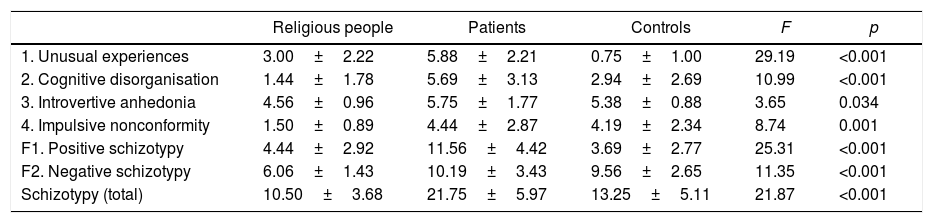

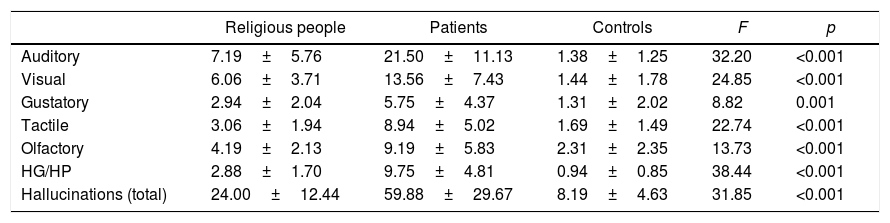

H2 was that patients would score high in schizotypy and hallucination compared to evangelicals and the control group, which was confirmed with schizotypy — F(21.75)=21.87 (p<0.001) — (Table 2) and with hallucination — F(59.88)=31.85 (p<0.001). In addition, it was found that they scored high in positive schizotypy (UE+CD) and negative (IA+IN) (both p<0.001) (Tables 2 and 3).

Comparison of religious people, patients and controls in schizotypy.

| Religious people | Patients | Controls | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Unusual experiences | 3.00±2.22 | 5.88±2.21 | 0.75±1.00 | 29.19 | <0.001 |

| 2. Cognitive disorganisation | 1.44±1.78 | 5.69±3.13 | 2.94±2.69 | 10.99 | <0.001 |

| 3. Introvertive anhedonia | 4.56±0.96 | 5.75±1.77 | 5.38±0.88 | 3.65 | 0.034 |

| 4. Impulsive nonconformity | 1.50±0.89 | 4.44±2.87 | 4.19±2.34 | 8.74 | 0.001 |

| F1. Positive schizotypy | 4.44±2.92 | 11.56±4.42 | 3.69±2.77 | 25.31 | <0.001 |

| F2. Negative schizotypy | 6.06±1.43 | 10.19±3.43 | 9.56±2.65 | 11.35 | <0.001 |

| Schizotypy (total) | 10.50±3.68 | 21.75±5.97 | 13.25±5.11 | 21.87 | <0.001 |

Comparison of religious people, patients and controls in terms of propensity to have hallucinations.

| Religious people | Patients | Controls | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auditory | 7.19±5.76 | 21.50±11.13 | 1.38±1.25 | 32.20 | <0.001 |

| Visual | 6.06±3.71 | 13.56±7.43 | 1.44±1.78 | 24.85 | <0.001 |

| Gustatory | 2.94±2.04 | 5.75±4.37 | 1.31±2.02 | 8.82 | 0.001 |

| Tactile | 3.06±1.94 | 8.94±5.02 | 1.69±1.49 | 22.74 | <0.001 |

| Olfactory | 4.19±2.13 | 9.19±5.83 | 2.31±2.35 | 13.73 | <0.001 |

| HG/HP | 2.88±1.70 | 9.75±4.81 | 0.94±0.85 | 38.44 | <0.001 |

| Hallucinations (total) | 24.00±12.44 | 59.88±29.67 | 8.19±4.63 | 31.85 | <0.001 |

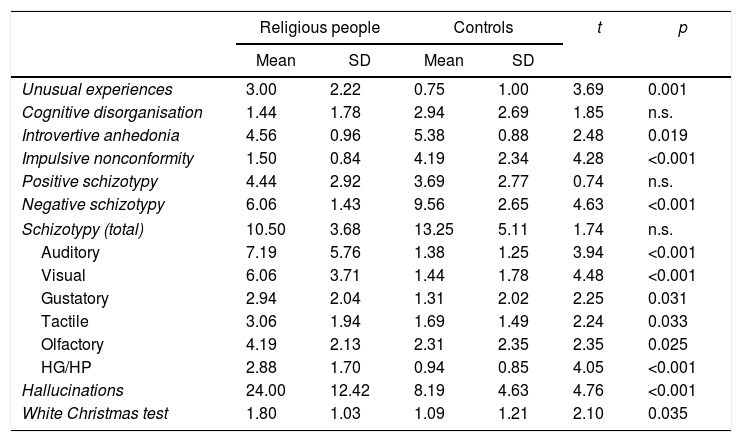

H3 was that the religious group would score higher in schizotypy, hallucination and WCT compared to the control group. This was confirmed with schizotypy; in fact, the religious group scored significantly lower in negative schizotypy (IA+IN) than the control group (p<0.001), but did not score higher in positive schizotypy (no significant differences). With regard to propensity to hallucinate, the religious group scored significantly higher than the non-religious control group (p<0.001) in all its sensory modalities. Lastly, the religious group scored higher in WCT than the control group (p=0.035) (Table 4).

Comparison of religious people, patients and controls in terms of schizotypy, propensity to have hallucinations and White Christmas Test.

| Religious people | Controls | t | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Unusual experiences | 3.00 | 2.22 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 3.69 | 0.001 |

| Cognitive disorganisation | 1.44 | 1.78 | 2.94 | 2.69 | 1.85 | n.s. |

| Introvertive anhedonia | 4.56 | 0.96 | 5.38 | 0.88 | 2.48 | 0.019 |

| Impulsive nonconformity | 1.50 | 0.84 | 4.19 | 2.34 | 4.28 | <0.001 |

| Positive schizotypy | 4.44 | 2.92 | 3.69 | 2.77 | 0.74 | n.s. |

| Negative schizotypy | 6.06 | 1.43 | 9.56 | 2.65 | 4.63 | <0.001 |

| Schizotypy (total) | 10.50 | 3.68 | 13.25 | 5.11 | 1.74 | n.s. |

| Auditory | 7.19 | 5.76 | 1.38 | 1.25 | 3.94 | <0.001 |

| Visual | 6.06 | 3.71 | 1.44 | 1.78 | 4.48 | <0.001 |

| Gustatory | 2.94 | 2.04 | 1.31 | 2.02 | 2.25 | 0.031 |

| Tactile | 3.06 | 1.94 | 1.69 | 1.49 | 2.24 | 0.033 |

| Olfactory | 4.19 | 2.13 | 2.31 | 2.35 | 2.35 | 0.025 |

| HG/HP | 2.88 | 1.70 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 4.05 | <0.001 |

| Hallucinations | 24.00 | 12.42 | 8.19 | 4.63 | 4.76 | <0.001 |

| White Christmas test | 1.80 | 1.03 | 1.09 | 1.21 | 2.10 | 0.035 |

The general aim of this study was to evaluate the auditory hallucinatory experience in a clinical sample of patients with a psychiatric history (such as schizophrenia), a group of religious people (such as devout evangelical Christians) and a control group (with no mental illness and non-religious). More specifically, we aimed to analyse the attributional bias associated with auditory hallucinations assessed with the WCT, compare WCT scores, positive/negative schizotypy and hallucinatory propensity in three groups (patients, religious people and controls), and relate the WCT score with schizotypy and the propensity to hallucinate. The results showed not only that patients scored high on the WCT compared to evangelicals as predicted, but also that evangelicals scored higher than the control group.

The results showed that the patients clearly demonstrated greater attributional bias (using the WCT) compared to the evangelicals and the control group, but that the religious group also tended to show greater bias (although to a lesser degree) than the control group. This indicates that the religious people, who are often characterised by experiencing mystical states in their worship, have a moderately greater tendency to attribute an external origin to their auditory experiences.

Patients also tended to show greater schizotypy and more hallucinatory experiences than evangelicals and the control group. Surprisingly, the control group tended to show greater negative schizotypy than the religious group (although no differences were found in the positive dimension), suggesting that practising religion may contribute to diminishing the negative effects (aggression, social isolation, etc.) of schizotypy. For example, the religious group showed a greater frequency of unusual perceptual experiences (hearing voices, seeing apparitions, etc.) and, in particular, a broader multisensory modality of hallucinatory experiences (auditory, visual, tactile, gustatory, and hypnagogic/hypnopompic) than those who did not practice any religion.

In general, we would argue that religious groups tend to show a greater frequency of positive perceptual experiences than the control group, and that patients show greater attributional bias of their auditory (and probably also visual) experiences. The main results of this study can be catalogued as follows. To begin with, according to previous studies,26,30 43% of the control participants said that they had heard the music (Mintz and Alpert stated 32%). In addition, the hallucinatory experiences were not related to greater auditory perception in the WCT. This finding further reinforces the conclusion of Young et al.31 that the experience of the WCT is not simply suggestion or fulfilling the expectations of the experimenter, as the subjects were unaware that the tune had not been recorded. That aspect is important for the following reason: the WCT showed that normal controls often interpret positively that there is actually a stimulus present, in the sense of a predisposition that a significant proportion of normal individuals has to have hallucinatory experiences.31

We are also able to conclude that the relatively high prevalence of hallucinations found in the general population does not necessarily demonstrate that normal people have persistent less intense and debilitating forms of schizophrenic symptoms, but that at least a large number of people tend to exaggerate their unusual perceptual experiences. It is clear that this area is worthy of further study. For example, it would be interesting in future studies to examine the links between the hallucinatory experience, attributional bias using tasks to assess other sensory modalities (e.g. visual or tactile) which might have important implications in the construction of magical thinking, creativity and other unusual perceptual experiences, such as paranormal experiences.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Parra A, Maschi G. Sesgo atribucional en pacientes psiquiátricos, religiosos y un grupo control en el juicio de la experiencia alucinatoria: la tarea del White Christmas test. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2018;47:82–89.