The spectrum of suicidal behaviour (SB) is nuclear in the clinic and management of borderline personality disorder (BPD). The pathological personality traits of BPD intervene as risk factors for SB in confluence with other clinical and sociodemographic variables associated with BPD. The objective of this work is to evaluate the specific personality traits of BPD that are related to SB.

MethodsA cross-sectional, observational and retrospective study was carried out on a sample of 134 patients diagnosed with BPD according to DSM-5 criteria. The Millon-II, Zuckerman–Kuhlman and Barrat questionnaires were used to assess different personality parameters. Variable comparisons were made using the χ2 test and the Student’s t-test. The association between variables was analysed using multivariate logistic regression.

ResultsStatistically significant differences were observed between SB and related factors and the neuroticism-anxiety dimension in the Zuckerman–Kuhlman test. It is also significantly related to the phobic and antisocial subscale of the Millon-II. Impulsivity measured with the Zuckerman–Kuhlman and Barrat tests does not appear to be related to SB.

ConclusionsThe results presented raise the role of phobic, antisocial and neuroticism traits as possible personality traits of BPD related to SB, suggesting an even greater importance within the relationship between BPD and SB than that of impulsivity. Looking to the future, longitudinal studies would increase the scientific evidence for the specified findings.

El espectro de la conducta suicida (CS) es nuclear en la clínica y el tratamiento del trastorno límite de personalidad (TLP). Los rasgos patológicos del TLP intervienen como factores de riesgo de CS en confluencia con otras variables clínicas y sociodemográficas asociadas con el TLP. El objetivo del presente trabajo consiste en evaluar los rasgos de personalidad específicos del TLP que se relacionan con la CS.

MétodosSe realiza un estudio transversal, observacional y retrospectivo, de una muestra de 134 pacientes con diagnóstico de TLP según los criterios del DSM-5. Se utilizan los cuestionarios de Millon-II, Zuckerman-Kuhlman y Barrat para valorar distintos parámetros de la personalidad. Se realizan comparaciones por variables mediante las pruebas de la χ2 y de la t de Student. La asociación entre variables se analiza mediante regresión logística multivariada.

ResultadosSe objetivan diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre la CS y relacionadas y la dimensión neuroticismo-ansiedad en el test de Zuckerman-Kuhlman. Asimismo se relaciona de manera significativa con la subescala fóbica y antisocial del Millon-II. La impulsividad medida con las pruebas de Zuckerman-Kuhlman y Barrat no aparece relacionada con la CS.

ConclusionesLos resultados presentados plantean el papel de los rasgos fóbicos, antisociales y del neuroticismo como posibles rasgos de personalidad del TLP relacionados con la CS. Incluso se propone una importancia mayor que el de la impulsividad dentro de la relación del TLP con la CS. De cara al futuro, estudios longitudinales permitirían aumentar la evidencia científica de los hallazgos presentados.

In Spain, suicide is the main cause of unnatural death and it is responsible for twice as many deaths as traffic accidents, 13 times more than homicides and 80 times more than gender violence.1–3 About 95% of patients who attempt suicide may meet criteria for at least one psychiatric diagnosis.4,5 Affective disorders are the most common diagnosis, followed by substance use disorder (especially alcohol), schizophrenia, and personality disorders, especially borderline personality disorder (BPD).6–8

BPD has a multifactorial aetiology and is characterised by emotional instability, a chronic feeling of emptiness, and suicidal or related behaviours (SB).9,10 SB is often core to the BPD construct, and is one of the most important targets for treatment and the most frequent source of conflict for clinicians.11,12 Forty percent to 85% of patients with BPD attempt suicide, with an average of three suicide attempts (SA) per patient.13,14 The completed suicide rates are between 5% and 10%, some 400 times higher than the estimate for the general population.13,15,16

The personality traits of patients with BPD are involved to some extent in these behaviours, which act as mediating factors between the personality structure and the expressed or manifest behaviour.17,18 The pathological features of BPD intervene as risk factors for SB in confluence with other clinical and sociodemographic variables associated with BPD, such as a history of trauma in childhood or previous SA.8,19–21

Suicide risk assessment is one of the most important and simultaneously complex tasks that any clinician must face, since BPD constitutes a particularly difficult group in the treatment of SB.11,22,23 Some of these personality traits may be SB risk markers and being able to identify them early would help improve therapeutic adherence, prognosis, and treatment of these patients with SB.24–26

To this end, the objective of this paper is to evaluate the specific personality traits of BPD related to SA and nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI).

MethodsStudy designThis is a cross-sectional, observational and retrospective study that aims to analyse the relationships between different personality traits and the subsequent presentation of SB in a sample of patients with BPD.

ParticipantsThe sample consisted of 134 patients between the ages of 18 and 56, diagnosed with BPD according to the DSM-5 criteria.27 These patients were recruited consecutively in the admission process to the Personality Disorders Day Unit of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos in Madrid (Spain). This is a specific and national reference unit for the treatment of patients with this diagnosis. The sample is divided into two groups according to whether they had a history of SB, on the one hand, or whether they presented with NSSI.

Patients meeting criteria for other diagnoses, including those with an IQ <85, severe neurologic disease, a history of traumatic brain injury, serious medical illness, current use of psychoactive substances (except tobacco), or refusal to participate in the study, were excluded. The hospital ethics committee approved the assessment protocol and all participants signed the informed consent.

Procedure, variables and instrumentsThe clinical evaluation was carried out with a questionnaire that assesses possible SA and NSSI and the modality of the SA. Likewise, the following questionnaires and interviews were used as personality measurement instruments:

- •

Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (MCMI-II).28 This provides empirically validated, relevant and reliable information on individual personality traits. It has four indices that enable evaluation of the validity of the protocol and 24 clinical scales grouped according to the degree of severity: clinical personality patterns, severe personality disorder, clinical syndromes, and severe clinical syndromes.28,29

- •

Zuckerman–Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire (ZKPQ).30 This measures the dimensions that constitute the model of the alternative five personality factors. It is based on the assumption that the “basic” personality traits are those with a strong biological-evolutionary basis29: impulsivity and sensation seeking, which is the sum of two subscales (impulsivity, understood as lack of planning and taking action without hardly any thought, and the sensation-seeking subscale, which includes the tendency to take risks, the search for arousal etc.); neuroticism-anxiety, which refers to being frequently worried, tense, upset, fearful, indecisive, lacking in self-confidence, and very sensitive to criticism; aggressiveness-hostility, which describe a readiness to express verbal aggression, rude, thoughtless and antisocial behaviour, vengefulness and impatience with others; sociability, which is divided into two subscales (parties and friends, which measures the number of friends, the time spent with them and the pleasure of attending parties and social gatherings, and intolerance of isolation, which indicates a preference for company of others in contrast to being alone and doing solitary activities), and activity, which is divided into two subscales (general activity, which describes the need for continuous general activity and an inability to rest when there is nothing to do, and work effort, which measures preference for challenging and difficult jobs, as well as a high degree of energy to work and multitask).

- •

Barrat Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11).31 This measures the degree of impulsivity with 30 items. The results are divided into three indices or subscales: attentional, motor, and nonplanning impulsivity, in addition to the total score. According to the authors, from the clinical point of view the total score is more important. In some studies, the median of the distribution of the values reached by the scale in the studied population is proposed as the cut-off point, but it can be understood that the scale itself does not have a predetermined cut-off point.29

Subjects were evaluated individually by a psychiatrist and a clinical psychologist for approximately 120min in the Personality Disorders Unit of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid (Spain). In order to minimise variability, all tests were performed at similar times (between 10:00am and 12:00pm).

Statistical analysisMean±standard deviation was used to describe continuous data and percentages were used for categorical data. Regarding the quantitative variables, their adjustment to normal distribution was determined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The sample was divided into two groups based on whether or not there was a history of SB and whether or not there was NSSI. Comparisons between variables were made using the χ2 and the Student’s t tests. The association between variables was analysed using a multivariate logistic regression model. For data analysis, the SPSS statistical package, version 19.0, was used. The significance level for all hypothesis contrast tests was p<0.05.

ResultsOf the 134 patients participating in the study, 97 were women (72.3%) and 37 were men (27.6%). The mean age of these patients was 30±8.74 (range, 18–56) years. The main patient sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Socio-demographic variables of the sample.

| Sex (n=134) | |

| Male | 37 (27.6) |

| Female | 97 (72.3) |

| Ethnicity (n=134) | |

| Caucasian | 116 (86.6) |

| Latin American | 3 (2.5) |

| Other | 3 (2.5) |

| Marital status (n=114) | |

| Single | 83 (72.8) |

| Married or partnership | 26 (22.8) |

| Divorced or separated | 5 (4.4) |

| Children (n=134) | |

| No | 109 (81.4) |

| Yes | 25 (18.6) |

| Number of children (n=134) | |

| 0 | 109 (81.4) |

| 1 | 15 (11.2) |

| 2 | 7 (5.2) |

| 3 or more | 3 (2.2) |

| Current activity (n=134) | |

| Unemployed | 78 (58.2) |

| Working | 16 (11.9) |

| Student | 24 (17.9) |

| Time off work | 16 (11.9) |

| Dependent (n=134) | |

| Yes | 107 (79.9) |

| No | 27 (20.1) |

| Level of education (n=134) | |

| Primary | 18 (13.5) |

| Secondary | 53 (39.8) |

| Professional training | 27 (20.3) |

| University studies | 35 (26.6) |

| Socioeconomic level (n=134) | |

| Low | 20 (22.7) |

| Middle-low | 37 (42) |

| Middle-high | 31 (35.2) |

Values are expressed in terms of n (%).

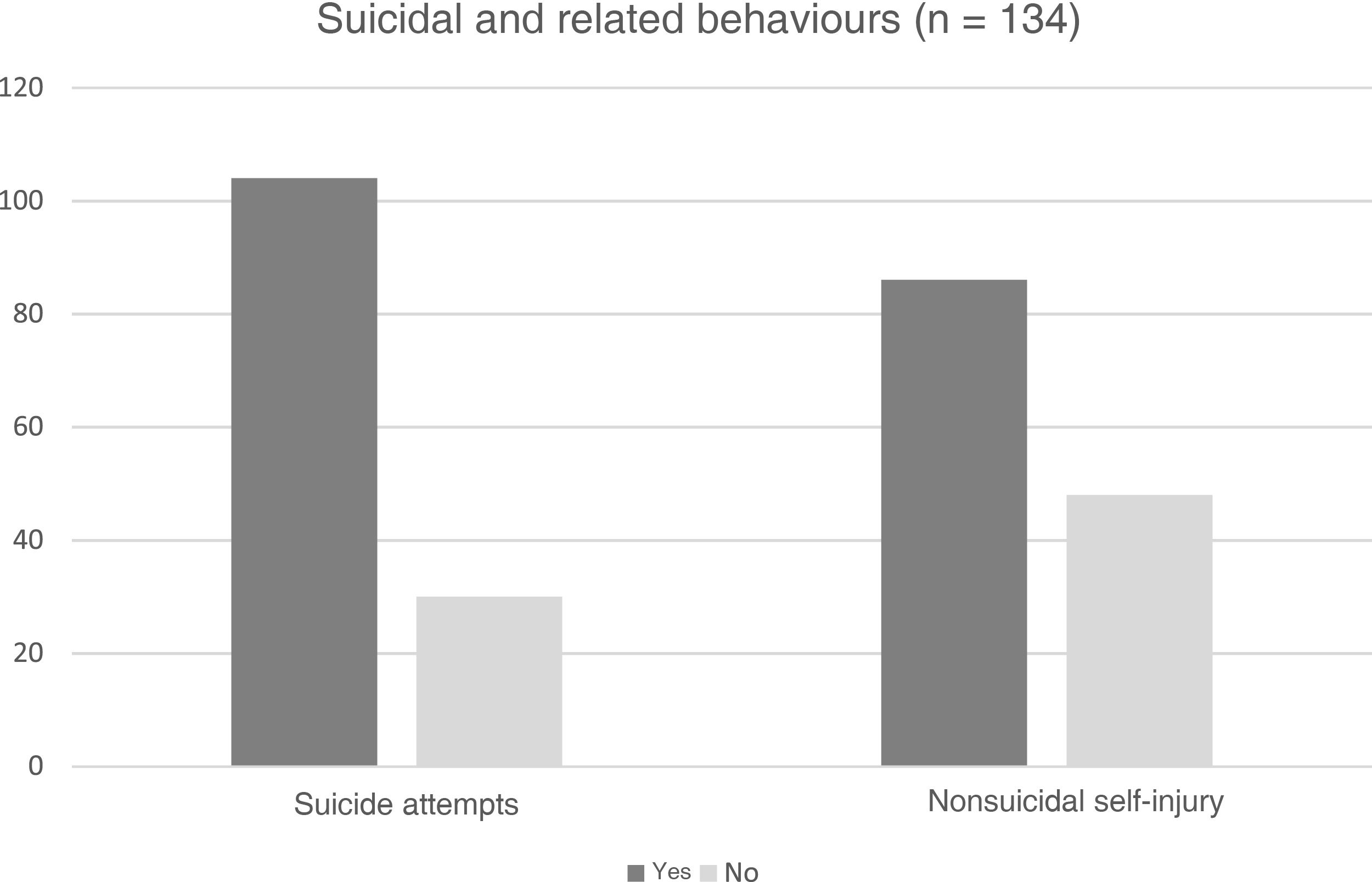

Of the 134 patients (77.6%), 104 reported a history of at least one SA, while 30 patients (22.4%) had no history of SB (Fig. 1). The mean SA/patient was 2.69±1.77. On the other hand, 86 patients (64.2%) reported a history of NSSI, while 48 (35.8%) did not (Fig. 1). The distribution of SA methods is shown in Table 2. The most frequent method was the combination of methods (53.5%), followed by drug overdose (46.5%). Table 3 shows the different means and medians of the subscales of the ZKPQ, MCMI-II and BIS-11.

Method of attempted suicide in the sample studied.

| Drug overdose | |

| Yes | 40 (46.5) |

| No | 46 (53.5) |

| Venoclysis | |

| Yes | 6 (7) |

| No | 80 (93) |

| Poisoning | |

| Yes | 1 (1.2) |

| No | 85 (98.8) |

| Hanging | |

| Yes | 1 (1.2) |

| No | 85 (98.8) |

| Fall from height | |

| Yes | 6 (7) |

| No | 80 (93) |

| Stab wound | |

| Yes | 1 (1.2) |

| No | 85 (98.8) |

| Jumping in front of a vehicle | |

| Yes | 2 (2.3) |

| No | 84 (97.7) |

| Other methods/combination of methods | |

| Yes | 46 (53.5) |

| No | 40 (46.5) |

Values are expressed in terms of n (%).

Scores on the different scales of the ZKPQ, MCMI-II and BIS-11 questionnaires.

| Mean±standard deviation | Median | |

|---|---|---|

| ZKPQ (n=73) | ||

| Neuroticism-anxiety | 14.79±4.29 | 17 |

| Activity | 7.49±3.42 | 7 |

| Sociability | 6.1±3.94 | 6 |

| Impulsivity and sensation seeking | 9.81±5.12 | 10 |

| Aggressiveness and hostility | 9.48±3.33 | 10 |

| MCMI-II (n=68) | ||

| Schizoid | 73.07±27.08 | 70 |

| Avoidant | 79.62±25.99 | 83 |

| Dependent | 63.49±35.88 | 72.5 |

| Histrionic | 66.56±29.9 | 68.5 |

| Narcissistic | 66.38±32 | 70 |

| Antisocial | 78.53±28.23 | 79 |

| Aggressive–sadistic | 73.47±27.46 | 73 |

| Compulsive | 54.65±28.98 | 51 |

| Passive–aggressive | 88.24±26.78 | 91.5 |

| Masochistic | 86.24±21.2 | 90.5 |

| Schizotypal | 84.14±25.07 | 82 |

| Borderline | 94.2±24.26 | 101.5 |

| Paranoid | 71.38±20.44 | 67 |

| BIS-11 (n=113) | ||

| Motor | 24.3±7.87 | 25 |

| Non-planning | 24.02±8.14 | 24 |

| Attentional | 20.6±5.36 | 21 |

BIS-11: Barrat Impulsiveness Scale; MCMI-II: Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory; ZKPQ: Zuckerman–Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire.

According to the univariate analysis of the SA (Table 4), statistically significant differences were observed in their association with the scores on the t test for the equality of means in ZKPQ, sociability dimension (p=0.044). This variable appears to have a protective effect, that is, the higher the score, the less association of BPD with SA. Likewise, the scores in the t test for equality of means in ZKPQ, neuroticism-anxiety dimension (p=0.061) are close to statistical significance.

Results of the Student’s t test for the equality of means of suicide attempts.

| p (Bilateral) | Mean difference (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| BIS-11 | |||

| Motor | 0.538 | 1.123 | (–2.476 to 4.721) |

| Non-planning | 0.377 | 1.662 | (–2.050 to 5.375) |

| Attentional | 0.456 | 0.923 | (–1.524 to 3.370) |

| Total | 0.424 | 3.371 | (–4.957 to 11.698) |

| ZKPQ | |||

| Impulsivity | 0.923 | –0.149 | (–3.203 to 2.905) |

| Neuroticism-anxiety | 0.061 | 2.22 | (–0.283 to 4.724) |

| Aggressiveness and hostility | 0.980 | –0.025 | (–2.010 to 1.960) |

| Activity | 0.737 | 0.345 | (–1.693 to 2.383) |

| Sociability | 0.044 | –2.356 | (–4.641 to –0.070) |

| MCMI-II | |||

| Schizoid | 0.882 | 1.159 | (–14.413 to 16.731) |

| Avoidant | 0.880 | 1.135 | (–13.807 to 16.076) |

| Dependent | 0.229 | 12.404 | (–8.002 to 32.810) |

| Histrionic | 0.747 | –2.784 | (–19.964 to 14.396) |

| Narcissistic | 0.640 | –4.322 | (–22.692 to 14.048) |

| Antisocial | 0.473 | –5.846 | (–22.017 to 10.325) |

| Aggressive–sadistic | 0.589 | –4.288 | (–20.045 to 11.468) |

| Compulsive | 0.997 | 0.029 | (–16.640 to 16.698) |

| Passive–aggressive | 0.977 | 0.226 | (–15.175 to 15.627) |

| Masochistic | 0.966 | –0.264 | (–12.458 to 11.929) |

| Schizotypal | 0.340 | 6.885 | (–7.431 to 21.200) |

| Borderline | 0.946 | –0.476 | (–14.425 to 13.473) |

| Paranoid | 0.933 | 0.5 | (–11.253 to 12.253) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; BIS-11: Barrat Impulsiveness Scale; MCMI-II: Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory; ZKPQ: Zuckerman–Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire.

According to the univariate analysis of the NSSI, the scores on the t test for the equality of means in ZKPQ, neuroticism-anxiety dimension (p=0.031) and in MCMI-II, avoidant (p=0.045) and antisocial (p=0.027) subscales appear as risk factors (Table 5).

Results of the Student’s t test for the equality of means of methods of nonsuicidal self injury.

| p (Bilateral) | Mean difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| BIS-11 | ||

| Motor | 0.519 | –1.005 (–6.155) |

| Non-planning | 0.316 | 1.614 (–6.344) |

| Attentional | 0.442 | 0.815 (–4.185) |

| Total | 0.779 | 1.014 (–14.281 |

| ZKPQ | ||

| Impulsivity | 0.62 | 0.616 (–4938) |

| Neuroticism-anxiety | 0.031 | 2.216 0.212–4.219) |

| Aggressiveness and hostility | 0.448 | –0.613 (–3.201) |

| Activity | 0.187 | 1.09 (–3.261) |

| Sociability | 0.322 | –0.945 (–3.783) |

| MCMI-II | ||

| Schizoid | 0.828 | –1.475 (–26.994 |

| Avoidant | 0.045 | 12.88 0.317–25.443) |

| Dependent | 0.485 | 6.272 (–35.641) |

| Histrionic | 0.676 | –3.127 (–29.772) |

| Narcissistic | 0.487 | –5.57 (–31.788) |

| Antisocial | 0.027 | –15.339 (–27.12) |

| Aggressive–sadistic | 0.59 | –3.704 (–27.32) |

| Compulsive | 0.568 | –4.148 (–28.83) |

| Passive–aggressive | 0.12 | 10.341 (–26.215) |

| Masochistic | 0.083 | 9.113 (–20.662) |

| Schizotypal | 0.188 | 8.217 (–24.666) |

| Borderline | 0.175 | 8.192 (–23.85) |

| Paranoid | 0.835 | 1.064 (–20.372) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; BIS-11: Barrat Impulsiveness Scale; MCMI-II: Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory; ZKPQ: Zuckerman–Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire.

Impulsivity measured with the ZKPQ and BIS-11 tests does not appear to be related to SB or the NSSI according to the univariate analysis (Tables 4 and 5).

With the multivariate analysis using logistic regression, a statistically significant association is found between SB and NSSI (odds ratio [OR]=3.218; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.069–9.690; p=0.038). In turn, NSSI is associated in a statistically significant way with SA (OR=4.037; 95% CI, 1.491–10.932; p=0.006).

DiscussionThis study found a strong statistical association in the multivariate analysis between NSSI and SB in patients diagnosed with BPD, a finding also present in other studies.32,33 It was found that NSSI is a greater predictor of SA than the reverse, that is, that SA with respect to NSSI, as indicated by recent works.34–36 We can see that they are closely related, and a continuum can be formed in the expression of a basic malaise common to them.37

Despite some differences in the empirical findings, with different estimates of the importance of some pathological personality traits or others in BPD, it remains a widely accepted theory that patients diagnosed with BPD are at high risk of suicidal and related behaviours.8,21,38,39 This is widely corroborated data, about which there are few discussions. The difficulties begin when analysing BPD in terms of different personality traits and the criteria that define its diagnosis, as well as the degree of contribution of each one of these factors separately in the development of SB.20

Among the personality disorders most closely related to SB are BPD and antisocial personality disorder.40 The comorbidity of both may jointly increase the risk of SB, compared to that of each of the diagnoses separately,41,42 as well as determining worse psychosocial functioning.43,44

Self-inflicted injury is a pattern of self-destructive behaviour that includes NSSI, SA, and death by suicide, and comorbidity between BPD and antisocial personality disorder has been shown to foster them.45,46 The analysis carried out does not find a significant relationship with SA, but it does with NSSI according to the univariate analysis. Therefore, it makes sense to think that a patient affected by BPD with antisocial personality traits presents with a greater tendency towards NSSI as a precursor to SB.

Regarding phobic traits, there are publications that relate them to SB.47,48 Cognitive rigidity, rumination, thought suppression, the feeling of belonging, the perception of being a burden or attentional biases are some cognitive factors related to SB that may be part of the symptomatic procession of patients with BPD and a higher score in phobic traits.49 It is possible that these patients with phobic traits have characteristics of self-aggression framed not in behavioural inhibition deficits, but in a more obsessive/pan-neurotic model of an inability to stop the desire to harm themselves, and show discomfort and anxiety during the process of restraining from the behaviour, but a significant relief when the act is carried out.50

In the sample of patients studied, a statistically significant relationship was found according to the univariate analysis among the personality dimensions measured by the ZKPQ questionnaire30 of neuroticism-anxiety, as a risk factor for NSSI. The neuroticism-anxiety dimension refers to being frequently worried, tense, upset, fearful, indecisive, lacking in self-confidence, and very sensitive to criticism.29 If this level of neuroticism is high, the subjects have unrealistic ideas, difficulties in tolerating frustration, excessive needs, or a tendency towards psychological distress.51,52

High levels of neuroticism and low levels of extraversion are associated with SB49 Systematic reviews on personality traits correlated with suicidal behaviour propose that neuroticism is a risk marker.6,24 Based on the univariate analysis, the analysis presented indicates that this dimension could predict NSSI. It could be affirmed that the patients with BPD who are more prone to worrying, being tense, lacking in self-confidence and being sensitive to criticism would be more prone to NSSI as a precursor to SB itself.

Contrary to several authors and previous relatively consolidated evidence, no statistically significant relationship has been found between SB and impulsivity or aggressiveness, which are frequent characteristics or personality traits in these patients that could be found to be associated with SB or NSSI.53–55 One possible explanation is that not all suicidal and related behaviours are associated with aggressive-impulsive behaviours.56 Likewise, impulsivity is a heterogeneous conceptual construct, that is difficult to define clinically and phenomenologically in a unitary way.55 For this reason, it is considered useful to distinguish between state impulsivity and trait impulsivity. The first would be a characteristic of the suicidal act, which can appear fleetingly, and the second is an implicit or structural characteristic of the subject making an attempt, a more stable characteristic over time.57

Impulsivity measured with the Barrat scale (BIS)31 is the trait impulsivity subtype, which is not as defining of SB or NSSI rated as impulsive or non-planning, as state impulsivity.56 Impulsivity measured with the ZKPQ scale30 is the sum of two subscales: impulsivity, understood as lack of planning and taking action without hardly any thought, and the sensation-seeking subscale, which includes the tendency to take risks, the search for arousal, etc.29 In this line, several authors state that impulsivity and other temperament traits are not good predictors of SB.20,58 Other authors state that childhood trauma, especially sexual abuse, would be a better predictor of SB than impulsivity.19,59–61 However, as will be seen later, the cross-sectional design of the study may have influenced the absence of this finding.

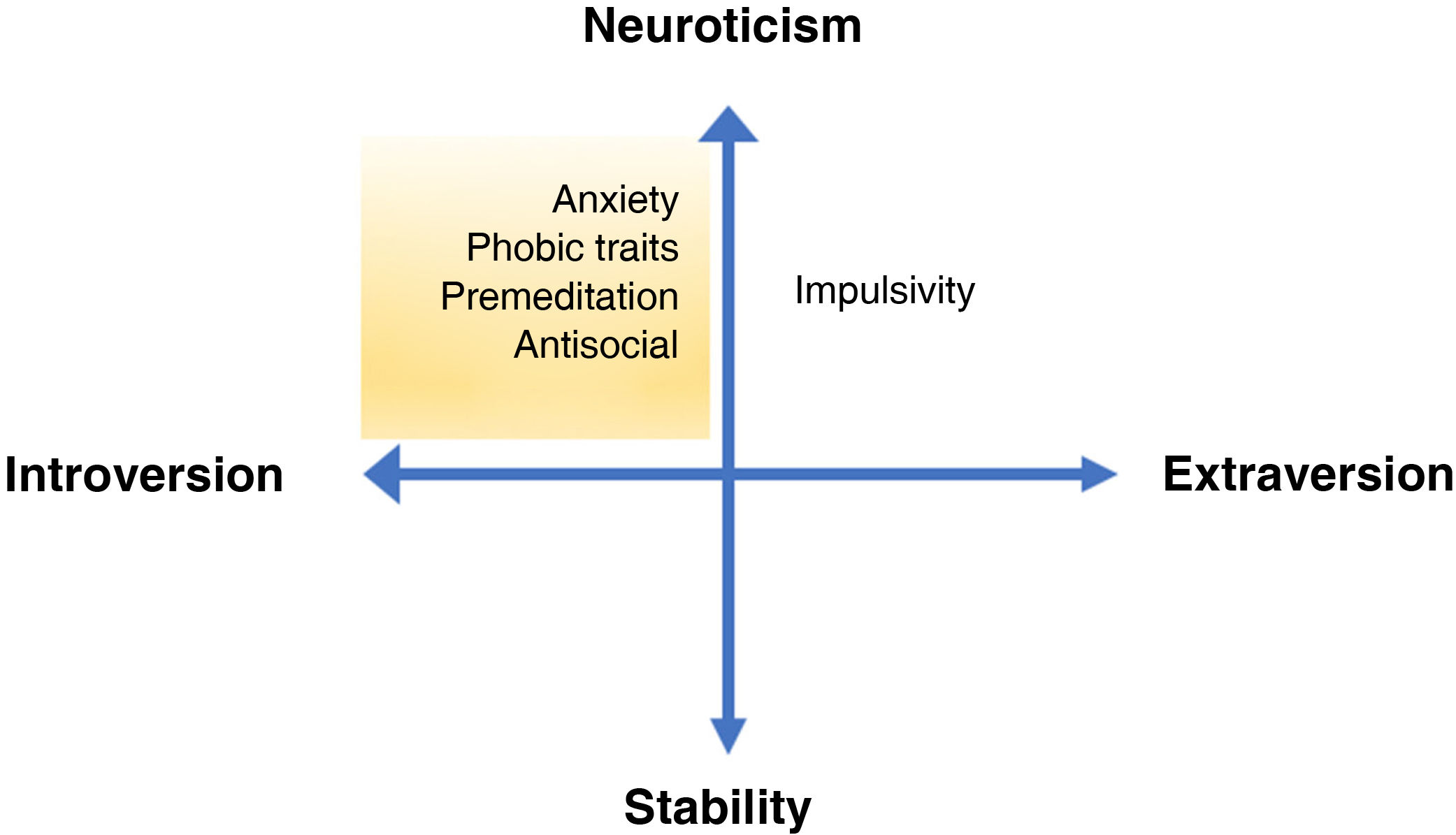

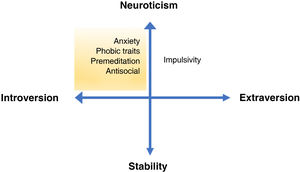

In summary, combining personality traits in the introversion-extraversion and neuroticism-stability dimensions,62 it is evident that patients with BPD who are more prone to introversion and neuroticism (in which patients with more phobic, neurotic or antisocial traits could be included) have a higher risk of SB than those more prone to extraversion (the most impulsive) or stability (Fig. 2).

Gray’s model adapted to the basic dimensions of borderline personality disorder. The neuroticism-stability (vertical axis) and introversion-extraversion (horizontal axis) personality dimensions are presented, with examples of typical traits of each dimension. The area of greatest suicide risk according to the findings described is shaded in yellow.

The main methodological limitation of the design of this study is that it is an observational, descriptive and cross-sectional study, concurrent and retrospective in time. This design model does not allow for the establishment of causal links between the associations found and does not have the statistical power comparable to that of a prospective study.

ConclusionsThe results presented raise the role of phobic, antisocial and neurotic traits as possibly SB-related personality traits of BPD, with greater importance proposed even than that of impulsivity within the relationship of BPD with SB. These results could be complementary to further research projects with a view to their inclusion in SB assessment scales and clinical treatment within the comprehensive treatment for this disease.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.