Harmful alcohol use is a public health problem worldwide, contributing to an estimated 5.1% of the global burden of illness. Screening and addressing at-risk drinking in primary care settings is an empirically supported health care intervention strategy to help reduce the burden of alcohol-use problems. In preparation for introducing screening and treatment for at-risk drinking in primary care clinics in Colombia, we conducted interviews with clinicians, clinic administrators, patients, and participants in Alcoholics Anonymous. Interviews were conducted within the framework of the Detección y Atención Integral de Depresión y Abuso de Alcohol en Atención Primaria (DIADA, [Detection and Integrated Care for Depression and Alcohol Use in Primary Care] www.project-diada.org) research project, and its qualitative phase that consisted of the collection of data from 15 focus groups, 6 interviews and field observations in 5 regional settings. All participants provided informed consent to participate in this research. Findings revealed the association of harmful alcohol use with a culture of consumption, within which it is learned and socially accepted practice. Recognition of harmful alcohol consumption includes a social context that influences its screening, diagnosis and prevention. The discussion highlights how, despite the existence of institutional strategies in healthcare settings and the awareness of the importance of at-risk drinking among health personnel, the recognition of the harmful use of alcohol as a pathology should be embedded in an understanding of historical, social and cultural dimensions that may affect different identification and care scenarios.

El consumo nocivo de alcohol es un problema de salud pública en todo el mundo, que contribuye a aproximadamente el 5.1% de la carga mundial de la enfermedad. La detección y el abordaje del consumo nocivo de alcohol en atención primaria es una estrategia de intervención de atención en salud empíricamente respaldada para ayudar a reducir la carga de los problemas de consumo de alcohol. En preparación para introducir pruebas de detección y tratamiento para el consumo nocivo de alcohol en clínicas de atención primaria en Colombia, realizamos entrevistas con médicos, administradores clínicos, pacientes y participantes en Alcohólicos Anónimos. Las entrevistas se realizaron en el marco del proyecto de investigación Detección y Atención Integral de Depresión y Abuso de Alcohol en Atención Primaria (DIADA, www.project-diada.org), y su fase cualitativa consistió en la recopilación de datos en 15 grupos focales, 6 entrevistas y observaciones de campo en cinco entornos regionales. Todos los participantes proporcionaron consentimiento informado para participar en esta investigación. Los hallazgos muestran la asociación del consumo nocivo de alcohol con una cultura de consumo, en la cual esta se expresa como una práctica aprendida y socialmente aceptada. El reconocimiento del consumo nocivo de alcohol incluye un contexto social que influencia su detección, diagnóstico y prevención. La discusión resalta cómo, a pesar de la existencia de estrategias institucionales en el contexto de atención en salud y de la conciencia sobre la importancia del consumo nocivo de alcohol entre el personal sanitario, el reconocimiento del uso nocivo del alcohol como una patología debe estar integrada con la comprensión de las dimensiones históricas, sociales y culturales que pueden afectar diferentes escenarios de identificación y atención.

Risky alcohol use is a major public health concern - it can worsen outcomes for many general medical and psychiatric illnesses and is a risk factor for road traffic accidents and violence. The World Health Organization (WHO) notes that alcohol consumption is a unique risk factor for population health as it affects the risks of infectious diseases, noncommunicable diseases and injuries.1 In fact, 5.9% of all deaths on a global scale (a total of 3.3 million deaths annually) can be attributed to harmful alcohol use. Moreover, an estimated 5.1% of the global burden of disease and injury can be attributed to alcohol.2 Public health approaches to address this disease burden include the regulation of the physical availability of alcohol, the imposition of taxes, the alteration of the context in which alcohol is consumed, education and persuasion, the regulation of the promotion of alcohol, the implementation of measures to manage drunkenness, and the promotion of treatment and early intervention.3

Implementing promotion and early intervention for mental health problems in primary care has been proposed as a key strategy in the Latin American region.4 Standardized screening and brief interventions for harmful alcohol use have been widely tested and shown to work5–10 but are rarely used in routine practice in primary care settings. This may be, in part, because addressing unhealthy alcohol use requires culture change for its implementation within the healthcare community, a sophisticated understanding of local sociocultural attitudes towards alcohol, and consistent public policies regarding alcohol use and its economic impacts. For example, an Australian study demonstrates how sociocultural factors can influence detection and intervention for risky alcohol use at the primary care settings. There was consensus that “detecting at-risk drinking is important but difficult to do, social and cultural attitudes to alcohol consumption affect willingness to ask questions about its use, the dynamics of patient-doctor interactions are important, and alcohol screening questionnaires lack practical utility.” Analysis suggests that the conceptual barriers to detecting at-risk drinking were: community stigma and stereotypes of “problematic drinking”, General Practitioner’s (GP) perceptions of unreliable patient alcohol use histories, and the perceived threat to the patient-doctor relationship”.11 Other comparative studies show no difference between implementation settings.7

In particular, in Colombia, alcohol use is a significant public health concern and varies by gender. Data from the 2015 Colombian National Mental Health Report demonstrated that 12.0% of the population between 18 and 44 years old have risk factors for harmful alcohol use, with a higher prevalence of harmful use within males (16.0%) than in females (9.1%).12 For the adult population above the age of 45, the prevalence of harmful alcohol use is 6.0%–10% in the male population, compared to 3.2% in the female population.13 These data demonstrate that the gap between the prevalence of harmful alcohol use in men and women is much larger in older adults than in younger populations that consume alcohol.13,14

Current mechanisms exist within Colombian public policy that target the harmful use of alcohol and include various guidelines established by the World Health Organization (WHO).15 One of the regulatory frameworks implemented in 2010 in Colombia is the 120 Decree that aims to protect minors and the community at large from the effects of harmful alcohol use by implementing strategies that reduce harm, minimize the risk of accidents, violence and crime. It also includes the promotion of responsible consumption of alcohol using practices that mediate the culture of consumption characteristic of the population.16 The state imposed several other strategies, policies and plans to address the problem of harmful alcohol use. The National Strategy for a Comprehensive Response to Alcohol Consumption is a critical example of one of these plans that strives to implement mechanisms for the prevention and reduction of the social and public health consequences associated with harmful alcohol use and to promote inter-institutional and community strengthening with regards to alcohol consumption and its effects.17 Of equal importance. The National Plan for Health Promotion, Prevention and Psychoactive Substance Consumption Care in Colombia, seeks to reinforce institutions, promote mental health, as well as supporting programs of prevention, treatment and harm reduction.18 All these regulations face a challenge in their operationalization since they are related to community relations, socio-cultural matters and particular ways in which alcohol consumption is understood both by community and health personnel.

This article presents the results of a qualitative study conducted with primary care stakeholders that sought to identify the sociocultural practices associated with the harmful use of alcohol and provide evidence to support the embedding of care models.

MethodsThis qualitative research was conducted within the framework of the Detección y Atención Integral de Depresión y Abuso de Alcohol en Atención Primaria (DIADA) research project. A collaborative between Dartmouth College in the United States and Javeriana University in Colombia, part of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Research Partnership for Scaling Up Mental Health Interventions in Low-and Middle Income Countries, with the purpose of carrying out evidence-based interventions that promote the screening and treatment of depression and harmful alcohol use within primary health care. This project involves using standardized screening, interventions, and mobile applications to strengthen mental health care within the primary care context as a step in the implementation strategy. The protocol study was approved by the ethics committees at the Javeriana’s School of Medicine in Colombia and Dartmouth College in the U.S.

One phase of the multi-phase project was implemented within five sites with patients, health and administrative personnel and community organizations. This phase consisted of the collection of data through 15 focus groups with Medical Personnel, Administrative personnel and patients, 6 interviews (conducted in 2017 across all sites) and field observations. An anthropologist conducted this portion of the qualitative phase in April of 2018. All participants provided informed consent to participate in this research. When presenting specific information, a number will identify the sites in order to preserve site confidentiality.

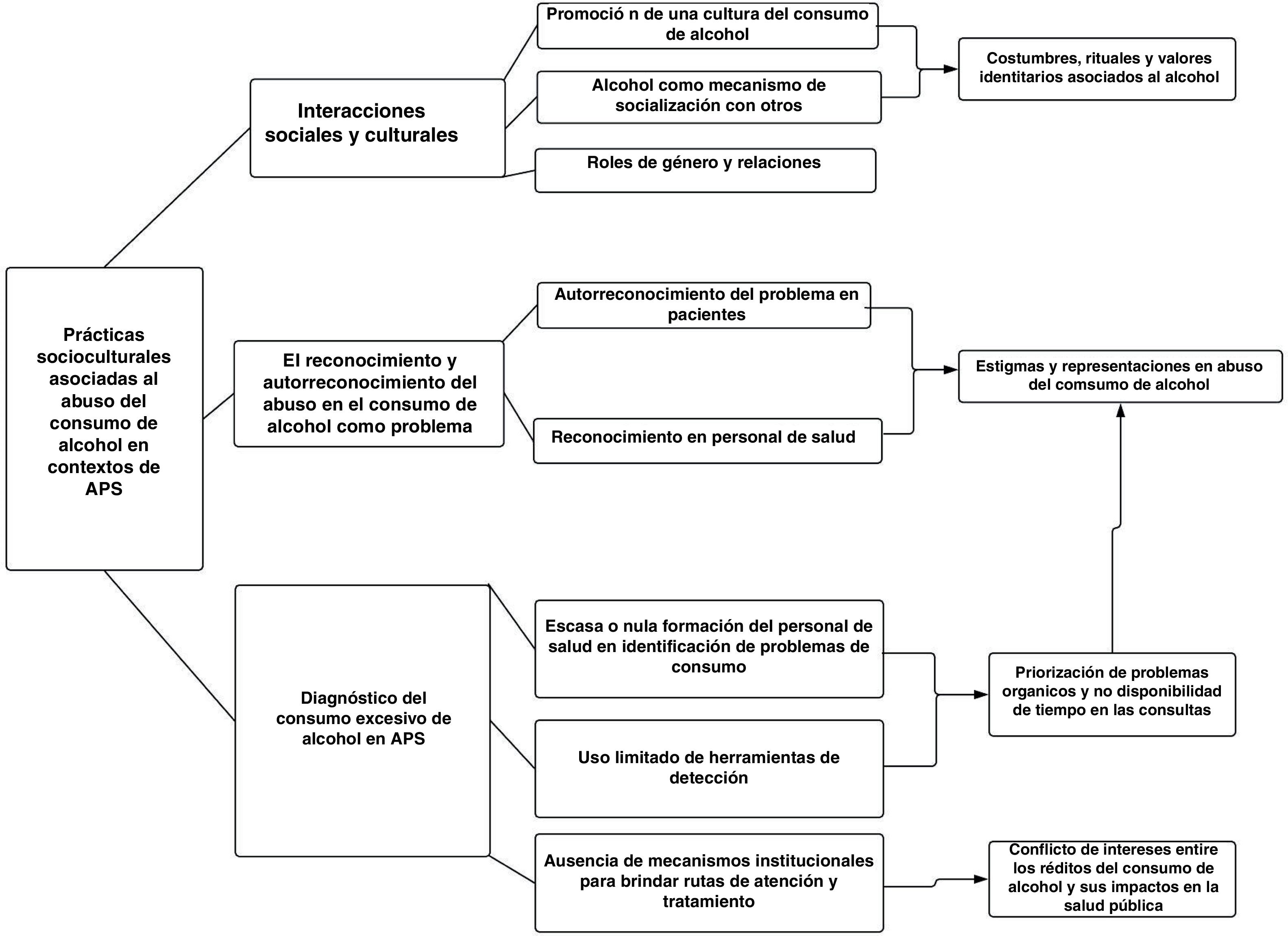

The data collected was first transcribed and systematized using NVivo 11 Software following the 6 phases proposed by Lorelli et al. for the “thematic analysis process”,19 which includes: familiarizing with data, generation of initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining themes and report production. Within the transcriptions, the analytic team defined the following themes: “socio-cultural practices and alcohol”, “socio-cultural practices”, “recognition and self-recognition of harmful alcohol use”, “Diagnosis of harmful alcohol use”. Based on the triangulation between theoretical review and data analysis each of these themes were developed as different levels of sociocultural practices associated with the harmful use of alcohol in primary health care settings.

ResultsFig. 1 depicts the different levels of sociocultural practices associated with the harmful use of alcohol within primary care settings. Subsequently, the results derived from these levels are presented through references to, or extracts from, the qualitative information that was collected.

Social and cultural interactionsFindings from our qualitative research revealed the association of harmful alcohol use with a culture of consumption, within which it is expressed as a learned and socially accepted practice: “culturally, the harmful use of alcohol occurs every day. I believe that we grew up within an environment in which everyone from families to the individuals that surround them… have a culture of alcohol consumption. Before, I would have believed, it is my perception, before I would have been likely to give a drink to a minor, and say “go ahead, try it” … It is a socially accepted practice, that some people know how to manage, and others do not, when it gets out of hand is when medical problems occur” (Medical Personnel, Site 1, 2017).

In the majority of cultures, such socially accepted practices and interactions are articulated as everyday cultural activities such as festivities, celebrations, or rituals in which alcohol is a major element (20). One of the focus groups identified the association of the Catholic first communion ritual with the consumption of alcohol as a social norm: “… Take the example of celebrations, the first communion, what is done is that it is celebrated with alcohol. The normal thing for us to do is make a list of what we are going to drink and offer” (Alcoholics Anonymous Focus Group, 2017). In addition to this, in some rural regions it is common for children or minors to consume traditional alcoholic beverages such as “el guarapo” and “la chicha”, fermented beverages made from sugar cane extract or maize alongside adults during regional festivals, and to become intoxicated without any regulation from the authorities (Administrative Focus Group, Site 5 2017, and Medical Personnel Site 4, 2017).

This situation is also observed in one of the rural settings, where according to one of the nurses it is a norm for children to take “la chicha” to school as a snack, and where the intoxication of minors occurs frequently (Field Notes, March 20, 2018, Site 2). In this case, the consumption of alcohol is not related to a specific event or ritual. Thus, it appears that “la chicha” and “el guarapo” do not necessarily represent drinks that are solely used to celebrate but rather represent drinks for everyday use and all kinds of activities: “I had a patient that had cirrhosis and it was a surprise to him… This is the thing, here in the city one is used to not drinking all the time, but there [in rural areas] the consumption of “guarapo” occurs every day. I tell them, “no, if you go work, drink water or juice”, and they respond, “Juice and water are more harmful to me than [el guarapo], [el guarapo] in not a problem” (Focus Group site 1, 2017).

In addition to alcohol’s association with daily activities and cultural events, another practice that reinforces the regular consumption of alcoholic beverages, such as “el guarapo” or “la chicha” in these regions, is their production within the home. In some regions, these drinks are commercialized within places called “chicherías.” “Chicherías” according to information provided by the local health center, are the homes of families who possess the recipes for preparing the drink and have historically been in charge of its preparation as well as are places in which these drinks are consumed regularly. Additionally, based on observations made during a visit to a “chichería”, the low cost of these drinks enables the majority of the population to access “la chicha” and to drink at these locations, and have conversations and interactions while drinking (Field Notes, March 20, 2018, Site 2).

In this sense, another element to consider is the consumption of alcohol as a mechanism of socialization, used to create relationships with others. Medical personnel related that: “at social gatherings it is very common to give a person liquor because that is how it is. So, it does not look like a problem, but more a habit…” (Medical Personnel Focus Group Site 1 2017). Additionally, our participants identified the consumption of liquor as being encouraged by the media and at “rumbas” (parties) as a recreational habit (Users Association of Site 1). Indeed, for many it is considered the only source of entertainment: “when I leave here, from the hospital, I say “well, what am I going to do?” I go out onto the street and there is nothing, the only thing there are bars that are open all day with music for all. Here no one sees anything else outside…” (Medical Personnel Site 4, 2017).

Apart from the role of alcohol in processes of socialization, alcoholic beverages that are produced within these regions also generate a strong sense of identity and are considered “native” to the region. Participants in municipalities of Boyacá highlighted that: “The thing here is to try to instill people with the importance of avoiding the consumption of alcohol, but it is that here… Boyacá is recognized nationally for its production of beer. We have breweries in almost all municipalities, and we have wineries everywhere. We also have our own brandy and rum, and people are very regionalist about this, you know, it is part of the culture…” (Medical Personnel Focus Group, site 2, 2017).

From our qualitative results, and within the sociocultural practices that permeate the consumption of alcohol, we also identified a transversal axis in the sociocultural practices that mediate these relationships, which are gender relations. Gender relations take into account the roles that men and women fulfill within society and their effect on the consumption of alcohol, which in turn affects how this problem is approached and dealt with within primary health care settings. These gender relations were identified within a focus group in which alcohol was deemed as synonymous with virility and masculinity: “…If I drink every day and I am with a group of friends, I am considered the boar, the hard one. Because of this, I am considered “machísimo”, if you instead exercise you are considered the… the weird one and you are the one that needs help, or the one that is stingy or that kind of thing…” (Administrative Focus Group, Site 3, 2017).

The findings suggest that there was a much higher perception or recognition of female drinkers in Site 2 than in other regions. This comment complements individuals’ observations from the health center within this region, that it is common for women just like men to consume large amounts of alcoholic beverages such as “chicha” (Field Notes, March 20, 2018, Site 2). Unfortunately, it was not possible to corroborate the specific proportion of men to women that consume alcohol within the region with this qualitative data. Additionally, the administrative staff indicated that there are ritual practices associated with the consumption of “chicha” that are considered witchcraft. In this ritual, women’s underwear is dipped into the drink during its preparation, enabling the woman who owns the underwear to successfully infatuate the men around her (Field Notes, March 20, 2018, Site 2).

Finally, the relationship between alcohol, violence, and gender was exposed within our findings, mainly within family contexts and towards women. In Site 2 a focus group revealed that: “… You see the mistreatment of the woman and sometimes also the women that are drinking with their husbands. They leave fighting and the children suffer the consequences…” (Patient Focus Groups, Site 2, 2017).

Another focus group referenced aggression and interfamilial violence as a consequence of harmful alcohol use that can lead people to seek care (Site 3, 2017). In other words, harmful alcohol use tends to only be viewed as a problem or considered “important” once violence or mistreatment occurs at the intra-familiar level. This finding is important as it suggests that psychological interventions at the primary health care level tend to treat the consequences of harmful alcohol use, such as violence, rather than the source of the problem or the harmful alcohol use itself (Administrative Focus Group, Site 3, 2017).

Recognition and self-recognition of harmful alcohol useIn order to analyze results concerning the processes of the identification of harmful alcohol use as a problem within primary health care settings, it is important to highlight three different points of view from different actors in these processes.

Based on the interviews conducted with the health personnel, the lack of recognition of harmful alcohol use was most often justified by patients through arguments such as “I go out on the weekends, and sometimes I get drunk, but I never lose consciousness… or mothers of adolescents say “no, it’s normal” (Medical Personnel Focus Group, site 1, 2017). These citations imply that many individuals have an established relationship with alcohol as something that is consumed daily and is a habitual social practice rather than a problem or disease that is not only determined by biomedical parameters but also by socially established limits or the definition of “normal consumption” in different contexts. Indeed, a participant reported that the consumption of alcohol is considered normal as long as a person “does not lose his temper, and does not change his personality, it’s just a little sip and that’s it” (Users Association Focus Group, Site 1, 2017).

We also found that it is unusual for patients to schedule medical consultations or see medical professionals in order to address their harmful alcohol use. Many patients do not recognize the health risk due to their alcohol use. Indeed, a medical professional stated: ““I have not seen a single patient that has visited me for problems related to alcohol abuse. The patients say, “I have high blood pressure, I have diabetes, and I have a multitude of other things, I drink alcohol, I drink beer on the weekend, I like to drink, but I do not see the problem with this. If the patient can’t even recognize his own symptoms, how can he even try to or say no [to alcohol], it is a problem that is very complex to treat, approach and to manage” (Focus Group, Site 2, 2017). The latter implies that the detection or diagnosis of harmful alcohol faces a common problem with other chronic or silent diseases that is the interpretation of symptoms, consequences and health effects from alcohol or other life style factors.

However, when harmful alcohol use is recognized, family is the fundamental actor within this detection process. The familial social circle helps the patient recognize his/her problem: “The last person to say yes I accept that I have a problem is the person with the problem, but the first to detect it, if it is a unified family, is the family” (Users Association, Focus Group, Site 1, 2017). Similarly, another interview mentioned that because some patients with harmful alcohol use disorder are not aware of their problem, family members are often consulted to confirm whether the patient does indeed struggle with harmful alcohol use (Social Worker Interview, Site 3, 2017).

At the primary health care level, harmful alcohol use is oftentimes not recognized or treated as a pathology due to its perceived complexity: “It is very complicated, therefore, to think about these complex pathologies, so a pathology due to alcohol… (laughter), not here” (Medical Personnel, Site 2, 2017). Other medical personnel justified their reluctance to treat patients with harmful alcohol use due to their lack of training on how to manage these types of cases, which results in the frequent avoidance of the problem within this setting (Health Personnel Focus Group, Site 1, 2017). This avoidance was further justified by health personnel as a complete disregard of the harmful use of alcohol as a disease among the staff: “We have been with doctors, and there are some that do not know or we go with psychologists who should know and they say: “that is a disease? A bad habit yes, but a disease?” (Alcoholics Anonymous, Focus Group, 2017).

Other participants view the recognition of harmful alcohol use as a two-way problem produced by the lack of self-recognition on behalf of the patients and the unpreparedness of the health personnel to treat the issue: “then, if I go, not for gastritis but (in a one in ten thousand occurrence) I got to my doctor to tell him: “help me, I am an alcoholic”, because for us (characteristics of an alcoholic is the negation of the problem), but let’s say that I accept and I go and tell him that I am an alcoholic, ¿What will my EPS doctor tell me? For this there is no acetaminophen, for that there is nothing, total ignorance?” (Alcoholics Anonymous, Focus Group, 2017).

Education level is expressed also by health personnel as an influential factor in the recognition of harmful alcohol use. During an interview, a health personnel expressed that he had a patient with a high risk of death due to harmful alcohol use whom, after overcoming the crisis, relapsed. The health personnel then explained that this was due to the fact that “he did not have a sufficient level of education, yes, in order to understand the magnitude of what was happening, of his illness…” (Social Worker Interview, Site 3, 2018). In contrast, another medical personnel stated that a person with a low educational level is more likely to strictly follow the doctor’s suggestions, while a person with a higher educational level would tend to question their recommendations, hindering the efficacy of the treatment and the credibility of the doctor (Focus Group, Site 1, 2017).

Besides education a health personnel said that it is the existence of “preconceptions” that patients have with regards to being “stigmatized on a cultural level”, that cause non-compliance with regards to the recommendations or prescriptions of the doctor and is the source of the trouble they experience with accepting the diagnosis (Doctors Focus Group, Site 5, 2017). This difficulty caused by stigma and prejudice manifests itself in this manner: “No, it is that they are treating me as an alcoholic, but if I don’t drink every day” or “but I am not crazy” or “I am not a drug addict” (Doctors Focus Group, Site 1, 2017).

Both misrepresentations and education level of patients and community are associated with the harmful use of alcohol, on top of the low attention by health personnel to the role that promotion and prevention has in this process.

Diagnosis of harmful alcohol useDespite the existence of globally validated tools for the diagnosis of harmful alcohol use, such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), there are low utilization rates or a complete lack of utilization of these tools in primary health care settings in Colombia. Although medical personnel are introduced to these tools during their training, many do not implement them within consultations or do not maintain medical records of the outcomes of the use of these tools, with the exception of some guidelines for the side effects of alcohol in specific cases (Doctors, Focus Group, Site 2, 2017). Some health personnel have reported that this is due to the test’s length and the short time available during consultations for its application (Medical Personnel Focus Group, IPS Bogotá, 2017) or due to the pressure of having to “quickly evacuate their patient” (Medical Personnel Focus Group, Site 2, 2017).

Similarly, the lack of use of these tools corresponds to institutional difficulties associated with the provision of support strategies, or the absence of specific routes through which patients with harmful alcohol use receive care within the health system (Doctors, Focus Group, Site 1, 2017). As reported in one of our focus groups, existing care routes in particular institutions cause “a patient that has harmful alcohol use, or other harmful use of psychoactive substances, to be tied up. There is nowhere to refer that patient, there are no agreements, that is, they provide short term care, and if the man after a crisis is stable… he goes home and from there follows the treatment” (Administrative Personnel Focus Group, Site 3, 2017). Likewise, administrative problems associated with contracts with institutions capable of providing specialized services for this group of patients often result in the discontinuity of treatment and follow-up of patients (Administrative Personnel, Site 3, 2017).

Limitations of institutional regulations for the harmful use of alcohol were also identified within focus groups: “… There is publicity that discourages drunk driving, but nowhere does drinking responsibly appear… The Ministry of Health and the Secretary of Health have produced a lot of publicity; however, this has not led to any results” (Focus Group, Site 1, 2017). The weakness of these institutional regulations was justified in one interview by the conflicts of interest that exist due to the economic benefits that alcohol generates within society: “…The government and its related institutions… are worried because the more alcohol that is consumed, the more money there is for health and other things… Our health policies are crushed by economic considerations, even if they contradict each other…” (Interview Hospital Psychiatrist, Site 4, 2017).

Sociocultural practices associated with harmful alcohol use within primary care settings are related to socio-cultural interactions, the recognition among clinicians and self-recognition among patients for alcohol use as a problem and the diagnosis within primary care centers. Within the collected data rituals and gender roles, stigma and lack of tools for self-recognition have equal importance as the lack of capacities of health personnel in the identification of harmful alcohol use.

DiscussionThe use of alcohol reflects a complex pattern that is deeply entwined with culture and meaning. Understanding its sociocultural role is critical to efforts to lessen its negative impact on health in primary care settings.

Practices and/or experiences associated with the consumption of alcohol are woven into routine daily social life in Colombia. In the media, as well as in daily traditional practices, alcohol can be seen as vehicle for interaction within society and is considered more of a tradition or a custom than a problem. This cultural interpretation of alcohol affects the process of screening and intervention for harmful alcohol use in primary care.

Historically, in Colombia alcoholic beverages were used in daily cultural practices, festivities, celebrations, and rituals and considered a key part of the diet. Given this history, alcohol can be symbolically linked to elements such as social solidarity,21 identity and in some cases can be linked with curative effects.22 In this sense it should be understood that drinking is not itself a carrier of a homogenous or standardized representation. On the contrary, social practices that occur within specific spatiotemporal contexts allow the consumption and use of alcohol to acquire differing values.21

Based on this notion, apart from their manufacturing processes, the distinction between fermented and distilled drinks is articulated through specific socio-cultural practices. Ever since pre-Hispanic and pre-colonial periods, the consumption of fermented drinks was not exclusively recreational. On the contrary, the consumption of “la chicha” and other artisanal drinks, was considered a key element of the diet for both adults and children, due to beliefs regarding their nutritional and energy benefits.22 Additionally, before the colonial period, indigenous villages considered the consumption of these beverages as a ritual conducted for therapeutic purposes.23

Furthermore, during this time period, the consumption of “la chicha” was popularized as a means to replace traditional protein sources such as meat, as it was more accessible due to its low manufacturing cost.22 It was also used as a stimulant for work. This association highlighted the positive effect of the consumption of this type of drink on productivity, which generated the large scale expansion of its consumption, as well as its commercialization and distribution within establishments called “chicherías”.24 However, an association was also developed during the colonial period, late nineteenth century and mid twentieth century, between the consumption of fermented drinks and the disturbance of public order, such as fights, due to drunkenness, crime, abandonment of work responsibilities, hygiene and health problems22. Furthermore, during this time period, indigenous rituals involving “chicha” were also considered as contradicting catholic morals. “Chicherías” were thus viewed as immoral and impure, and as being places of socialization in which obscene actions occurred.24

In contrast, distilled beverages were widely produced from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. Their introduction during the colonial period was linked to their use and consumption within festive, ritual and non-dietary contexts. Furthermore they were popular among all social classes and had a higher alcohol content than fermented drinks.23 In addition to this, from the thirteenth century until the beginning of the twentieth century, medical schools recognized the therapeutic properties of alcoholic beverages, especially those distilled for consumption and topical uses.22

This study’s findings indicate that alcohol consumption plays an important social and cultural role in festivities, social events and local practices.25 Because the consumption of alcohol is socially accepted in a multitude of contexts,20 patient’s self-recognition as well as the identification of harmful alcohol use by medical personnel face multiple barriers within the context of primary health care, as these processes of recognition do not exclusively subscribe to the biomedical parameters that define harmful alcohol use.

Additionally, within some regional contexts, the consumption of artisanal alcoholic drinks is associated with the strengthening of community ties, such as historically in some indigenous villages.26,27 Consequently, these types of beverages, including “la chicha” or “el guarapo,” are considered “unregulated”. However, regulatory policies have been developed for these drinks due to the large public health risks associated with their high levels of ethanol or levels of toxic substances such as methanol.17 Nevertheless, a strong cultural identity is rooted within the consumption of these drinks,17 which legitimizes their consumption as a cultural and traditional practice that is “normal” or “natural” in certain contexts.

It is also important to consider the social value associated with the consumption of alcohol that legitimizes, in certain scenarios such as festivities and celebrations, the ingestion of any type of beverage. However, if the consumption of alcohol occurs outside of these scenarios, it can be considered “abnormal” or “illegitimate”. This distinction enables the identification of the sociocultural rules associated with the consumption of alcohol within each society and the potential limitations of detection tools when dealing with issues of a sociocultural nature.11

We identified two effects of the socio-cultural nature of harmful alcohol use with regards to medical personnel. The first effect was the lack of knowledge about and need for the use of tools to detect harmful alcohol use, due to this level of consumption being a socially accepted practice. Amongst our interviews and focus groups, health personnel consistently evaluated harmful alcohol use as a “cultural problem” and not a medical one, which in some studies has been linked to the perception that these tools lack practicality.11 Secondly, some studies recognize that the stigma surrounding harmful alcohol use largely affects health personnel28–30; therefore, barriers related to the access of patients with harmful alcohol use to primary health care can be associated with medical personnel’s lack of knowledge regarding how to address this type of problem as well as patients’ fear of stigmatization from health personnel and from their social circle.

With respect to the identified gender relations, it is important to note the male and female roles that operate within scenarios of harmful alcohol use and form the basis of both the misrepresentations and stigmas surrounding alcoholic beverages. The results of the GENACIS project (Genres, Alcohol and Cultures: An International Study) compared the prevalence of intake in women and men in six countries (Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Mexico, Uruguay and USA). The results indicated that men drink more than women, that the prevalence of intense consumption is three four times more common in men than in women and that genres and cultures exert strong influences on the use and abuse of alcohol3). As shown in our results, data in the Americas show a greater proportion of men who consume alcohol compared to women,3 and that there are social norms related to alcohol consumption that based on a male dominated culture32 associates virility with the consumption of alcohol.33

However, it is also important to highlight the stigmas regarding women’s consumption of alcohol. Women who consume alcohol are often looked down upon in society and are considered to be contradicting their role in various social contexts as a mother or caregiver.32,34,35 Despite this, the number of women that consume alcohol has gradually risen in the Americas.3,31 According to one study, women with harmful alcohol use may be reluctant to express that they struggle with their alcohol consumption due to shame and guilt32 and may refuse to receive care due to these stigmas. The presence of gender relations associated with the consumption of alcohol suggests that adopting a gendered approach to the management of harmful alcohol use within primary health care settings may aid in its detection in both male and female populations. For example, the tools used for the identification of harmful alcohol use are limited in their ability to fully evaluate the life experiences related to alcohol consumption that are particular to men and women. To remediate this challenge, these tools should be applied differently depending on gender, and should address the differences that gender produces with regards to the problem of harmful alcohol use.34

In some social environments alcohol consumption generates greater social interaction, regardless of social position, and facilitates communicative skills.25 Alcohol’s role as a social facilitator was contrasted within our results by its use as a means of social exclusion with respect to non-consumers. This dichotomy further strengthens a culture in which the consumption of alcohol is promoted and accepted, which in turn influences the assessment of harmful alcohol use as a pathological issue.

Finally, and in light of the weakness associated with the implementation of regulatory frameworks for the harmful use of alcohol, it is important to recognize the economic interest that lies within the promotion and commercialization of alcohol consumption. As mentioned in one of our interviews, this economic interest can be more influential than regulations promoted at the policy level and guidelines regarding the consumption of alcohol. For example, studies carried out in four African countries have similarly highlighted the influence of the alcohol industry on legislative developments.36,37 The Panamerican Health Organization (PAHO) has highlight this relation as both a challenge and barrier in the promotion and prevention of problematic alcohol consumption.3 Furthermore, a systematic review of seventeen studies identified the influence of the alcohol industry on marketing regulatory frameworks, auto-regulation and the diffusion of information regarding the effectiveness of these regulations.36,38 Additionally, it is clear that the alcohol industry’s marketing strategy, within the processes of prevention and regulation, is more aimed towards the promotion of their product rather than the regulation of its consumption.3,39

Some limitations of the study should be noted. First, these conclusions cannot be extrapolated to other regions, even in the same country, since regional forms and meaning to the logics of alcohol consumption vary among them. Secondly, even though various stakeholders were included, some opinion groups may be not represented in the local qualitative data.

In addition, within the Latin American region protocols should consider gender as a structural issue that culturally mold alcohol use. In future studies, the perspective of gender, ethnicity and social class must be incorporated in data collection and analysis. Finally, the results from this qualitative phase can be complemented and contrasted with the actual implementation challenges once programs targeting alcohol use problems in the sites are rolled out.

ConclusionThe purpose of this study was to illustrate practices and relationships valued at a sociocultural level that are related to harmful alcohol use, and their possible impacts and repercussions within the identification of this disease within primary health care settings. Despite the existence of institutional strategies and the awareness of health personnel, the recognition of the harmful use of alcohol as a pathology requires the visualization of social and cultural dimensions that may affect different identification and care scenarios. This recognition will lead to a more efficient and effective adoption of detection and intervention tools and processes for patients and medical personnel – interventions that are adapted to the specific contexts in which they are applied.

As demonstrated in this report, harmful alcohol consumption is not seen in a single way; on the contrary, its manifestation lies in the dynamics, roles and representations present within each social context in which the consumption of alcohol has multiple connotations. This implies that in order to be successful, health strategies for the diagnosis and care of harmful alcohol use as a mental health problem should articulate these distinctive features.

Finally, it is important to analyze harmful alcohol use as more than a just a pathology or a problem but as a phenomenon that takes place in a social context. Understanding this context is crucial to engaging the patient and will enable a more nuanced and effective approach to the detection, diagnosis, and treatment of harmful use of alcohol in primary care.

DisclaimerThe views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

FundingResearch reported in this publication was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number 1U19MH109988 (Multiple Principal Investigators: Lisa A. Marsch, Ph.D. and Carlos Gómez-Restrepo, MD). The contents are solely the opinion of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH or the United States Government

Conflict of interestDr. Lisa Marsch, one of the principal investigators on this project, is affiliated with the business that developed the mobile intervention platform that is being used in this research. This relationship is extensively managed by Dr. Marsch and her academic institution.

Please cite this article as: Vargas S, Medina Chávez AM, Gómez-Restrepo C, Cárdenas P, Torrey WC, Williams MJ, et al. Abordando el consumo nocivo de alcohol en atención primaria en Colombia: entendiendo el contexto sociocultural. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:73–82.