Susac syndrome is a rare clinical condition, possibly mediated by an autoimmune process; the classic triad is composed of retinopathy, decreased hearing acuity and neuropsychiatric symptoms (encephalopathy). There are few cases reported with neuropsychiatric symptoms as the main manifestation. We present a case of Susac syndrome in a 34-year-old female with a predominance of neuropsychiatric symptoms, characterised by partial Klüver–Bucy syndrome, apathy syndrome, pathological laughter and crying, and cognitive dysfunction predominantly affecting attention, which showed a qualitative improvement with the use of immunological therapy. This case report highlights the importance of neuropsychiatric manifestations as clinical presentation in patients with neurological conditions.

El síndrome de Susac es una entidad clínica poco frecuente, posiblemente mediada por un proceso autoinmune; la tríada clásica se compone de retinopatía, disminución en la agudeza auditiva y síntomas neuropsiquiátricos (encefalopatía). Hay pocos casos descritos con sintomatología neuropsiquiátrica como la sintomatología principal. Presentamos un caso de síndrome de Susac, que corresponde a una mujer de 34 años, con predominio de sintomatología neuropsiquiátrica, caracterizada por un síndrome de Klüver-Bucy parcial, un síndrome apático, risa y llanto patológico y alteraciones cognitivas de predominio atencional; dichos síntomas mejoraron cualitativamente con el uso de terapia inmunológica. Este caso revela la importancia de las manifestaciones neuropsiquiátricas como presentación clínica en pacientes con entidades neurológicas.

Susac syndrome is a rare clinical condition possibly mediated by an autoimmune process.1 It was described for the first time in 1973, and was initially known as SICRET2 (small infarctions of cochlear, retinal, and encephalic tissue). Another term used to refer to this condition was RED-M (retinopathy, encephalopathy and deafness microangiopathy) syndrome.3 In 1979, Susac4 again described this clinical condition and in the following decade it was called Susac syndrome. This condition is characterised by involvement of the small arteries in the brain, the inner ear and the retina, which is why its classic clinical triad is made up of: encephalopathy with or without focal neurological deficit, loss of sensory hearing acuity and visual disturbance.4 Initially, this triad occurs in approximately 20% of patients. However, this figure increases to 70% as the condition progresses.5 Recently, the diagnostic criteria for the syndrome were published, which will help the study of this condition.6

The state known as encephalopathy is related to a deterioration in mental functions, which can generate neuropsychiatric manifestations. The following have been described in Susac syndrome: cognitive impairment in 48% of cases, confusion in 39%, emotional disorders in 16%, behavioural changes in 15%, personality changes in 12%, apathy in 12%, and psychosis in 10%.1 These figures are based on a retrospective review of all cases reported up to 2013. This review shows that neuropsychiatric manifestations, that is, mental and behavioural disturbances, are frequent, but more detailed clinical descriptions are required about the modes of presentation of these manifestations, since, without adequate guidance, mental and behavioural disturbances can be a source of diagnostic confusion. Neurological patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms are frequently referred to psychiatric hospitals without an adequate differential diagnosis. The purpose of this article is to present a clinical case of Susac syndrome, describe clearly the nature of the mental and behavioural disorders, and analyse it with the tools of a bibliographic review focused on the neuropsychiatric dimension of the problem. By adequately categorising acute neuropsychiatric symptoms, beyond the general concept of "encephalopathy", clinical suspicion and identification of the syndrome can be improved to obtain a greater number of scientific reports. The neuropsychiatric description of this case may help to give more visibility to Susac syndrome in the context of mental and behavioural disorders.

Regarding ethical considerations, informed consent for the study, guaranteeing confidentiality of the data, was given by both the patient and a first-degree relative.

Presentation of the clinical caseThe patient is a 34-year-old Mexican woman, with six years of schooling, right-handed, with no previous history of systemic, neurological or psychiatric diseases.

She presented disabling symptoms of vertigo lasting three days, six months before her hospitalisation. Also, two months before her hospitalisation, she had symptoms of tinnitus in the right ear for two days. The symptoms were self-limited and did not require medical management. One month before admission, the patient's partner observed a subacute onset of behavioural changes, characterised by visual-spatial disorientation, apathy and difficulty starting to walk. On a couple of occasions they also observed signs of hyperorality. For these reasons, she was admitted to a neurological referral centre.

During the first neuropsychiatric evaluation, the patient was awake (with a preserved sleep-wake cycle), with difficulty maintaining attention; she was distracted by environmental stimuli. Despite the stress implicit in her medical condition and the difficulties and discomforts of hospitalisation, she had a placid attitude. For example, she continued to smile politely, unusual within the hospital context and the circumstance of her illness. This, together with the previous report of hyperorality, led to it being considered a case of partial Klüver–Bucy syndrome. The patient's psychomotricity was greatly diminished, although she occasionally presented phenomena of environmental dependence (she picked up objects that were close to her to explore them despite receiving instructions not to pick them up). She did not speak spontaneously, only when questioned, and her responses were sparse, with increased response latency. Her voice was low in volume and monotonous. Her speech was poor in content, with generally monosyllabic responses. Despite being easily distracted by stimuli from her environment, when she was asked about her particular tastes in an attempt to stimulate her, she showed no interest. Initially, she did not present emotional behavioural reactions beyond her placid attitude. The APADEM-NH7 apathy scale was applied, in which she obtained a positive score in 42 items, related to the dimensions of cognitive inertia and self-generated behaviours. In this way, a syndrome of apathy with cognitive and self-activating characteristics was diagnosed. Regarding the exploration of other neurological symptoms, we found generalised hyperreflexia and Babinski's sign bilaterally. However, she did not show decreased strength. Initial laboratory tests were only positive for human chorionic gonadotropin. The obstetric evaluation revealed a pregnancy of 15 weeks of gestation, with a normal fetus. Consensus was reached with first-degree relatives and the pregnancy was therapeutically interrupted after the first line of treatment used (see below).

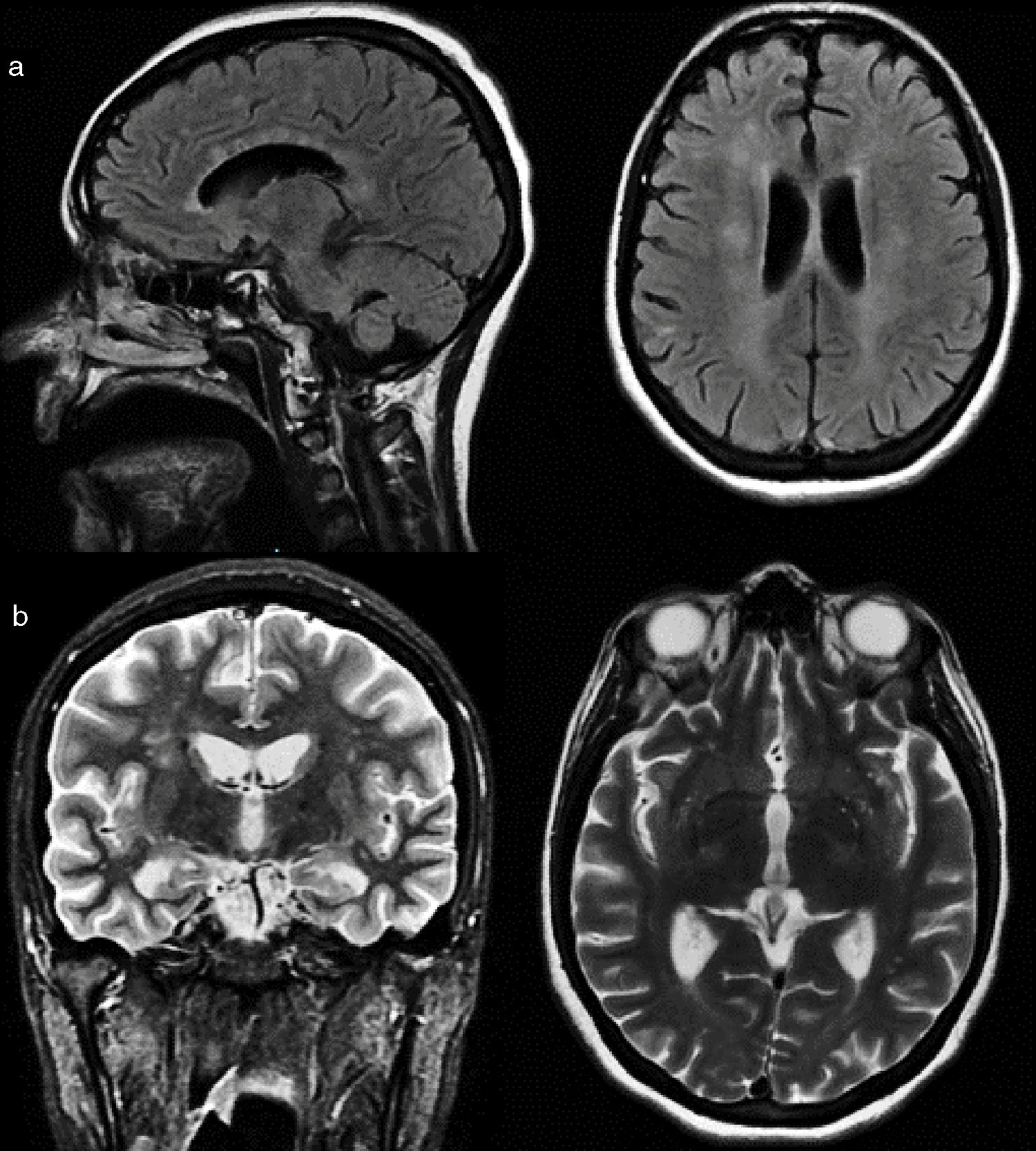

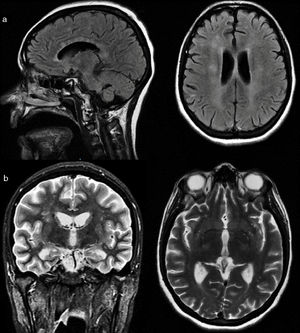

A magnetic resonance image (Fig. 1a and b) of the brain was performed, finding multiple bilateral hyperintense lesions in different regions of white matter such as the corpus callosum, corona radiata and periventricular regions, as well as in nuclei of grey matter, such as the caudate nucleus, in addition to cerebellar infratentorial regions.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. a) Sagittal and axial slices in FLAIR (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) sequence where hyperintense "snowball" lesions are observed in the corpus callosum, corona radiata and periventricular regions. b) Coronal and axial sections in T2 sequence, showing loss of volume of hippocampal structures and hyperintensities in the corona radiata and basal ganglia.

Lumbar puncture had a normal opening pressure. Cerebrospinal fluid of a liquid, transparent, colourless consistency was obtained, with proteins of 77 mg/dl, glucose of 52 mg/dl (serum glucose 89 mg/dl) and absence of cells. Fine speckled antinuclear antibodies (1: 2560) were found, without any systemic manifestation. The rest of the studies ordered (in search of paraneoplastic, infectious, autoimmune aetiology) did not present alterations.

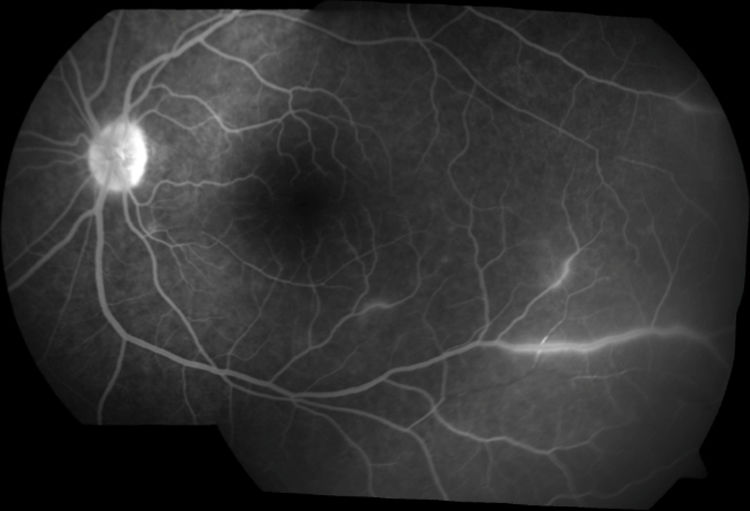

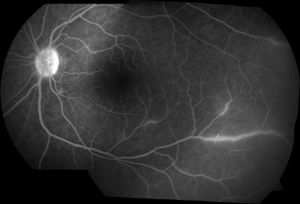

Ophthalmological evaluation by fluorescein angiography revealed occlusion of branches of the retinal artery (Fig. 2). Audiometric tests showed a bilateral hearing loss with a sensorineural pattern.

Treatment was started with boluses of methylprednisolone 1 g per day for 5 days, with poor clinical response. For this reason, treatment with immunoglobulin was started, calculated at a standard dose of 0.4 mg/kg/day for 5 days. The behavioural manifestations changed during the immunoglobulin treatment. The placid attitude continued throughout the course, but goal-directed behaviours increased. In addition, we observed a qualitative improvement in attention. An unexpected effect was that the patient began to present affective lability, going through affective incontinence and developing a clear pseudobulbar affect (that is, a loss of control of emotional expression, with episodes of uncontrollable laughing and crying, and unrelated to the subjective emotional state of the patient; as an example, she began to laugh in an exaggerated way the moment she interacted with the doctor and this generated shame, she constantly said that she did not want to laugh, that she was not laughing at the medical staff, but it was uncontrollable). The quantification on the PLACS scale for pathological laughter and crying8 was 15 points, of which 11 corresponded to the pathological laughter section and four to the pathological crying section.

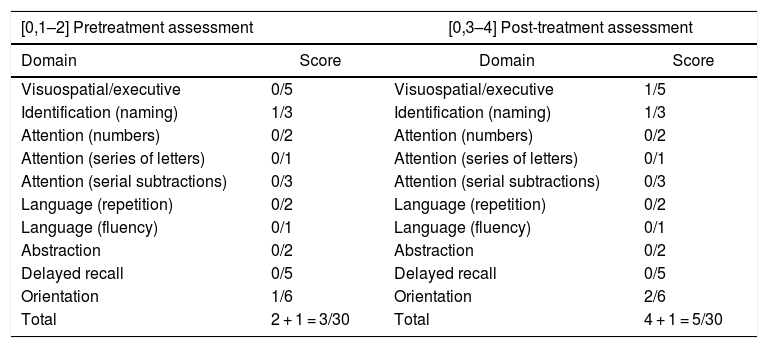

In the first assessment (Table 1) by the Neuropsychology Department, before treatment with methylprednisolone, data consistent with loss of initiative and low reactivity to environmental stimuli were found, as well as an alteration of attention, which generated secondarily an alteration of expressive language (very reduced spontaneous language, with primary preservation of automatic language, repetition and naming), language understanding, memory and executive functions.

Pre-treatment (day 2 of hospital stay) and post-treatment (day 20 of hospital stay) performance in the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Battery.

| [0,1–2] Pretreatment assessment | [0,3–4] Post-treatment assessment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Score | Domain | Score |

| Visuospatial/executive | 0/5 | Visuospatial/executive | 1/5 |

| Identification (naming) | 1/3 | Identification (naming) | 1/3 |

| Attention (numbers) | 0/2 | Attention (numbers) | 0/2 |

| Attention (series of letters) | 0/1 | Attention (series of letters) | 0/1 |

| Attention (serial subtractions) | 0/3 | Attention (serial subtractions) | 0/3 |

| Language (repetition) | 0/2 | Language (repetition) | 0/2 |

| Language (fluency) | 0/1 | Language (fluency) | 0/1 |

| Abstraction | 0/2 | Abstraction | 0/2 |

| Delayed recall | 0/5 | Delayed recall | 0/5 |

| Orientation | 1/6 | Orientation | 2/6 |

| Total | 2 + 1 = 3/30 | Total | 4 + 1 = 5/30 |

In the second neuropsychological evaluation, carried out after the immunoglobulin treatment, the patient was able to cooperate to a greater extent compared to the first evaluation. While the scores on the neuropsychological batteries remained quantitatively similar, her qualitative performance was better. The report of the second evaluation was as follows: "The patient is seen to have moderate to severe neuropsychological symptoms, characterised by adynamia and alterations in attention, memory, constructive praxis and executive functions. Unlike in the previous evaluation, there is an increase in activity, attention to interfering stimuli, environmental dependence, placidity and anosodiaphoria".

In the follow-up outpatient evaluation, three months after hospital discharge, the patient's neuropsychiatric status had improved considerably, with a clear persistence of the prefrontal manifestation (mainly executive domain and environmental dependence), as well as the pathological laughter and crying. In this follow-up period, the patient was dependent for complex activities of daily living but was beginning to perform some basic activities of daily living independently.

Discussion and conclusionsThe case we have presented illustrates some relevant characteristics of Susac syndrome. First, the triad characterised by encephalopathy, loss of auditory sensory acuity and visual impairment is fulfilled.4 Second, it is a case that probably obtained its maximum phenotypic expression due to the patient's pregnancy. There are some case reports where this relationship is described but, due to the level of evidence, we cannot reach causal conclusions in this regard.10,11 Third, the clinical response was demonstrated with the immunomodulatory treatment implemented in two stages. We will focus our discussion on the neuropsychiatric aspects.

As already mentioned, the term encephalopathy refers only to a diffuse brain disease and there is no consensus on the definition of this term from a clinical point of view. Therefore, during the clinical approach, a more detailed description is required, particularly of neuropsychiatric disorders, since these are often considered as "non-organic" or purely "psychological" in nature. However, an evidence-based clinical analysis can demonstrate that the alterations in the present case are closely linked to the objective brain damage that is encompassed by the term "encephalopathy". The patient presented alterations in attention, episodic memory and semantic memory, as well as in praxis and executive functions. This is consistent with the literature published so far. The affected cognitive domains that have been described in the case reports are mainly: attention deficits, language alterations, episodic and semantic memory impairment, visuospatial tasks, concrete thinking, impulsivity and psychomotor retardation.12,13

However, some of the neuropsychiatric manifestations of this case have not been described so far in the context of Susac syndrome, for which they merit their own discussion: namely, the elements of a (partial) Klüver–Bucy syndrome, the apathetic syndrome and the phenomenon of pathological laughter and crying. The three phenomena are linked to a well-documented neuroanatomical basis in the scientific literature and we will address them below:

- 1

Placidity is classically described in Klüver–Bucy syndrome14, as are the hyperorality behaviours reported by the family member. Although in the present case there is no bilateral lesion of the temporal lobe amygdala, it must be remembered that the involvement of multiple tracts of white matter can generate phenomena of corticolimbic disconnection. The amygdala of the temporal lobe establishes connections with the orbitofrontal cortex through the white matter of the uncinate fasciculus. In our patient, there are multiple lesions in the white matter of the frontal lobe, capable of altering the frontolimbic connectivity corresponding to the basolateral circuit of the amygdala. Placidity and hyperorality as such have not been described in Susac syndrome, although they could belong to the category of personality changes present in 12% of cases.

- 2

The definition of apathy according to Levy and Dubois15 consists of a reduction in goal-directed behaviours compared to a previous baseline and is divided into three dimensions: a) apathy due to failures in emotional-affective processing; b) apathy due to failures in cognitive processing (the most serious category of the three), and c) apathy due to a deficiency in auto-activation. In the case we describe, the patient had a mixture of cognitive processing and auto-activation components according to the analysis of the APADEM-NH scale and the behavioural quality observed during the examination. The anatomical regions described in these two subtypes of apathy correspond to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and its subcortical efferents, such as the dorsal caudate nucleus and the dorsomedial nucleus of the thalamus (which is associated with cognitive processing), in addition to the medial prefrontal cortex (corresponding to the auto-activation process). In the present case, a decrease in brain volume was observed in the medial frontal cortex, and also lesions in the white matter of the frontal lobe capable of interrupting the connections between the dorsolateral prefrontal circuit and its striato-thalamic efferents. Apathy has been described in up to 12% of cases of Susac syndrome.1

- 3

Finally, pseudobulbar affect or pathological laughter and crying is defined as episodes of uncontrollable laughing or crying inappropriate for the circumstances in which the patient finds him/herself and inconsistent with subjective monitoring of his/her emotional state. Some authors propose that this may be a continuum from affective lability to pseudobulbar affect.16 The alteration lies in a loss of voluntary control over emotional expression; this is due to disconnection processes. The classically described pathway is the cortico-ponto-cerebellar connection.16 In this case, we see multiple affected areas involving this tract. Pseudobulbar affect has not been previously described in Susac syndrome. It could be included in the section on emotional disorders (since it corresponds to a disorder of emotional expression), which are present in 19%.

The process by which neuropsychiatric syndromes are generated in this case is through disconnection of different anatomical regions, so it is to be expected that, as with the cognitive evaluations that have been described, the neuropsychiatric syndromes of this condition are heterogeneous, depending on injured anatomical structures. We consider that the neuropsychiatric description of this particular case may contribute to giving more visibility to Susac syndrome in the context of mental and behavioural disorders.

Finally, it is important to mention that this case offers several lessons. First, the relevance of the mental and behavioural examination in patients with "atypical" clinical pictures will allow us to make an appropriate approach and diagnosis. Second, clinical observation will lead us to the generation of hypotheses and the understanding of the functioning of the nervous system. Third, with this case we can broaden our clinical panorama in patients with this syndrome.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz-García RG, Chacón-González J, Bayliss L, Ramírez-Bermúdez J. Neuropsiquiatría del síndrome de Susac: a propósito de un caso. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:146–151.