Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a rare and potentially fatal drug adverse reaction. There are still few studies of this entity in the child–adolescent population.

ObjectivesDescribe the clinical, laboratory and therapeutic characteristics of children and adolescent patients with NMS. Analyse the grouping of symptoms present in NMS in the same population.

Material and methodsA MEDLINE/PubMed search of all reported cases of NMS from January 2000 to November 2018 was performed and demographic, clinical, laboratory and therapeutic variables were identified. A factorial analysis of the symptoms was performed.

Results57 patients (42 males and 15 females) were included, (mean age 13.65 ± 3.89 years). The onset of NMS occurred at 11.25 ± 20.27 days with typical antipsychotics and at 13.69 ± 22.43 days with atypical antipsychotics. The most common symptoms were muscle stiffness (84.2%), autonomic instability (84.2%) and fever (78.9). The most common laboratory findings were CPK elevation and leucocytosis (42.1%). The most used treatment was benzodiazepines (28.1%). In the exploratory factorial analysis of the symptoms we found 3 factors: 1) “Catatonic” with mutism (0.912), negativism (0.825) and waxy flexibility (0.522); 2) “Extrapyramidal” with altered gait (0.860), involuntary abnormal movements (0.605), muscle stiffness (0.534) and sialorrhoea (0.430); and 3) “Autonomic instability” with fever (0.798), impaired consciousness (0.795) and autonomic instability (0.387).

ConclusionsNMS in children and adolescents could be of 3 types: catatonic, extrapyramidal and autonomic unstable.

El síndrome neuroléptico maligno (SNM) es una rara y potencialmente fatal reacción adversa medicamentosa. Aún son pocos los estudios de esta entidad en la población infanto-juvenil.

ObjetivosDescribir las características clínicas, de laboratorio y terapéuticas de los pacientes niños y adolescentes con SNM. Analizar la agrupación de síntomas presentes en el SNM en la misma población.

Material y métodosSe realizó una búsqueda en MEDLINE/PubMed de todos los casos reportados de SNM desde enero del 2000 hasta noviembre del 2018 y se identificaron las variables demográficas, clínicas, laboratoriales y terapéuticas. Se realizó un análisis factorial de los síntomas.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 57 pacientes (42 varones y 15 mujeres), con edad promedio de 13,65 ± 3,89 años. La aparición del SNM ocurrió a los 11,25 ± 20,27 días (con antipsicóticos típicos) y a los 13,69 ± 22,43 días (con antipsicóticos atípicos). Los síntomas más frecuentes fueron la rigidez muscular (84,2%), inestabilidad autonómica (84,2%) y fiebre (78,9). Los hallazgos de laboratorio más frecuentes fueron la elevación del CK y leucocitosis (42.1%). El tratamiento más usado fue la indicación de benzodiacepinas (28,1%). En el análisis factorial exploratorio de los síntomas encontramos 3 factores: 1) «catatónico», con mutismo (0,912), negativismo (0,825) y flexibilidad cérea (0,522); 2) «extrapiramidal», con alteración de la marcha (0,860), movimientos anormales involuntarios (0,605), rigidez muscular (0,534) y sialorrea (0,430), y 3) «inestabilidad autonómica», con fiebre (0,798), alteración de la consciencia (0,795) e inestabilidad autonómica (0,387).

ConclusionesEl SNM en niños y adolescentes podría ser de 3 tipos: catatónico, extrapiramidal e inestable autonómico.

The symptoms associated with neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) were first described in 1956 by Ayd, and defined as such by Delay and Deniker in 1968, when they reported an unusual response to haloperidol.1 Initially, the term neuroleptic was used to describe those psychotropic drugs that controlled psychotic symptoms and produced extrapyramidal symptoms as a side effect — in other words, first-generation antipsychotics.2 Thus, NMS was described as a set of signs and symptoms that present as a potentially severe adverse reaction, secondary to the use of first-generation antipsychotics. However, over time it has been seen that it can also occur secondary to the use of atypical antipsychotics, mood stabilisers and even medication other than psychotropic drugs.

Initially, a prevalence of around 0.2%–3% was described in 1993,3 but in recent years a decrease in this has been observed, to 0.01%–0.02%,4 possibly due to greater care in the prescription and titration of medication. Four main symptoms are usually considered for its diagnosis: hyperthermia, muscular rigidity, altered consciousness and autonomic dysfunction. Added to these are diaphoresis, tremors, incontinence, leukocytosis and elevated creatine kinase (CK). Despite this, to date there is no consensus on universal diagnostic criteria.5

Although this adverse reaction can occur at any stage of life, in any gender and in people with both psychiatric and non-psychiatric illness, some risk factors associated with its appearance have been identified, such as advanced age, male gender, polypharmacy, dehydration, malnutrition, rapid administration of antipsychotics, structural brain damage and affective disorders.1,5 Among the main associated complications are the development of rhabdomyolysis, respiratory failure, kidney failure and sepsis, with a mortality of 5.6%. Among the predictive factors of mortality are advanced age, respiratory, renal and cardiovascular failure.6 It is, then, a widely described and studied syndrome, with various fatal complications. Despite this, there are still few studies in the child–adolescent population. Apparently, it is postulated that the course and treatment in children and adolescents is usually the same as in adults. However, more studies are needed in this regard.1,2 For this reason, the present work aims to describe the clinical and laboratory characteristics and the treatment of child and adolescent patients with NMS, and we will also analyse the grouping of the symptoms.

MethodsThe guidelines of the PRISMA Statement7 guide were followed. A search was carried out in the MEDLINE/PubMed search engine of all the reported cases of NMS from 1 January 2000 to 3 November 2018, entering the terms: (children OR child OR paediatric OR pediatric OR school child OR adolescents OR adolescence OR teenage) AND (case OR report OR case report OR case reports) AND (neuroleptic malignant syndrome). We selected the articles that met the following characteristics: articles written in English or Spanish and case reports or case series of NMS in people <18 years of age.

The identification and initial screening of the articles were carried out by the co-author (JHV). The titles and abstracts of all articles found were reviewed first; then two investigators (DLA, JHV) reviewed the full text of potentially relevant articles.

After a bibliographic review, it was decided to search in each case for the following variables: 1) demographic: age; gender; 2) clinical: fever; muscular rigidity; waxy flexibility; echophenomena (echopraxia, echolalia); mutism; negativism; abnormal involuntary movements; gait disturbance; dysarthria; dysphagia; hypersalivation; alteration of consciousness; autonomic instability; 3) laboratory tests: myoglobinuria; leukocytosis; thrombocytosis; hydroelectrolytic disturbances; altered liver enzymes; CK peak; increased LDH; 4) history of NMS: drug responsible for NMS; onset of symptoms (days); diagnosis and treatment of NMS. The data were extracted by the two investigators (DLA, JHV) independently, and any discrepancies later resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis was performed by one investigator (JHV). The percentages of each variable were found, as well as the average ages through the use of descriptive statistical techniques. Differences in the clinical picture, laboratory tests and treatment of NMS were searched for among the different antipsychotics responsible using the difference in two proportions test and analysis of variance (ANOVA).

An exploratory factor analysis was carried out with symptoms as variables, using the principal component analysis method, and then adjusted by Varimax rotation with Kaiser normalisation. The feasibility of performing a factor analysis of symptoms was evaluated using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and the Bartlett sphericity test. The number of factors was determined using the criterion of eigenvalue >1. The significance level of this study was 0.05. The data were analysed with the statistical program SPSS version 23 of IBM.

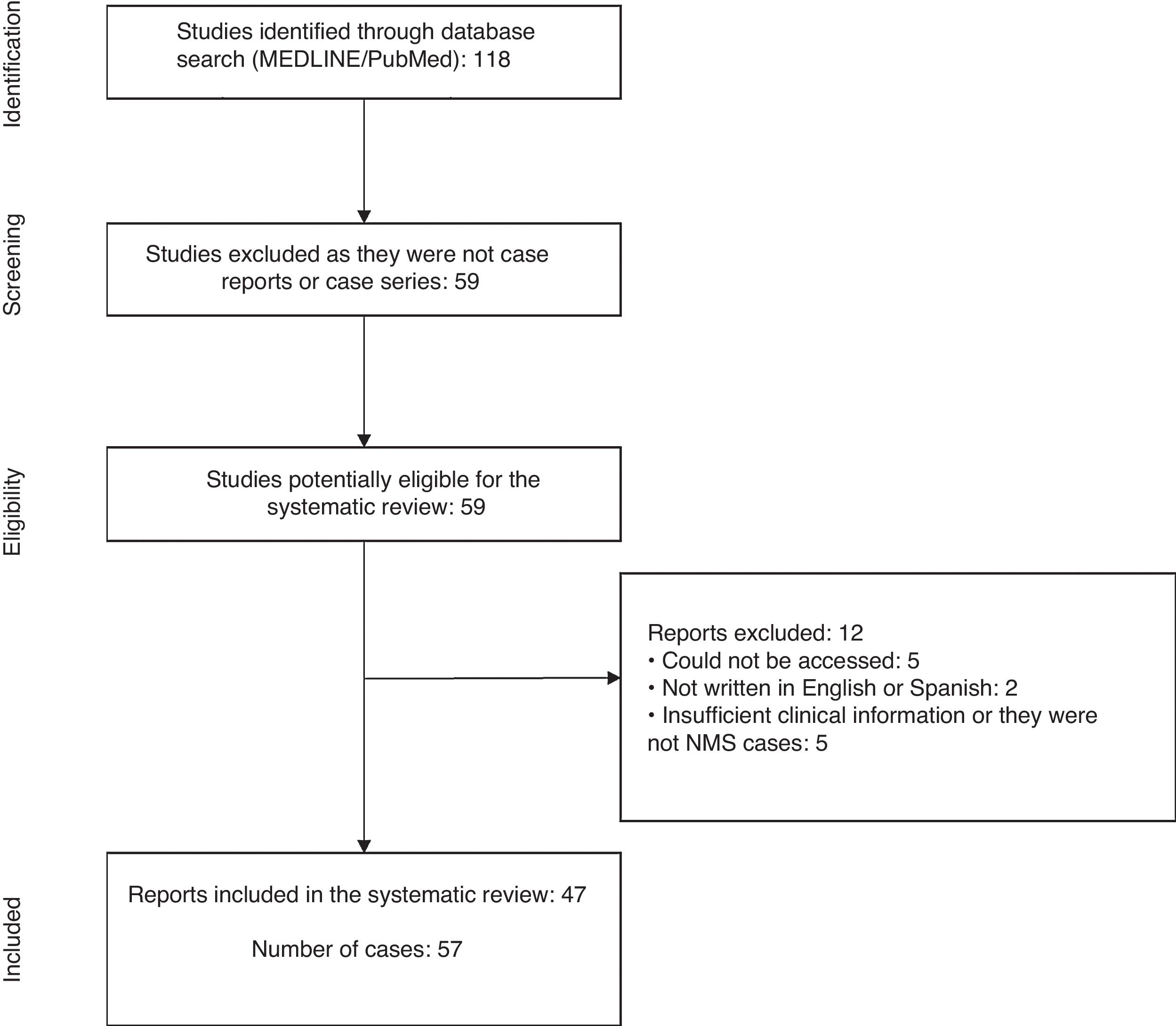

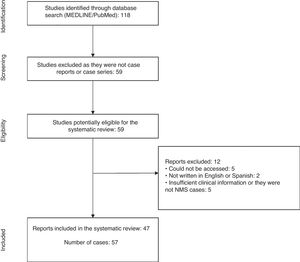

ResultsThe initial search yielded a total of 118 articles. Of these, 59 articles that were not case reports or series were discarded, leaving 59 articles with reports of cases of NMS in children and adolescents published between 1 January 2000 and 3 November 2018.1,3,8–64

From the review of these case reports, a total of 12 articles were excluded because the report was not accessible,56,60–63 was not written in English or Spanish,57,64 and did not have enough clinical data or was not a case of NMS.53–55,58,59 With the agreement of the investigators, 47 articles were included in the present study1,3,8–52 (Fig. 1).

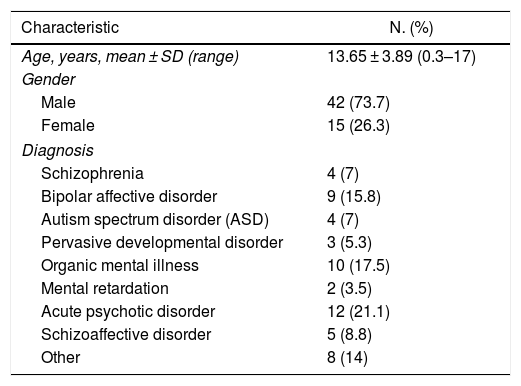

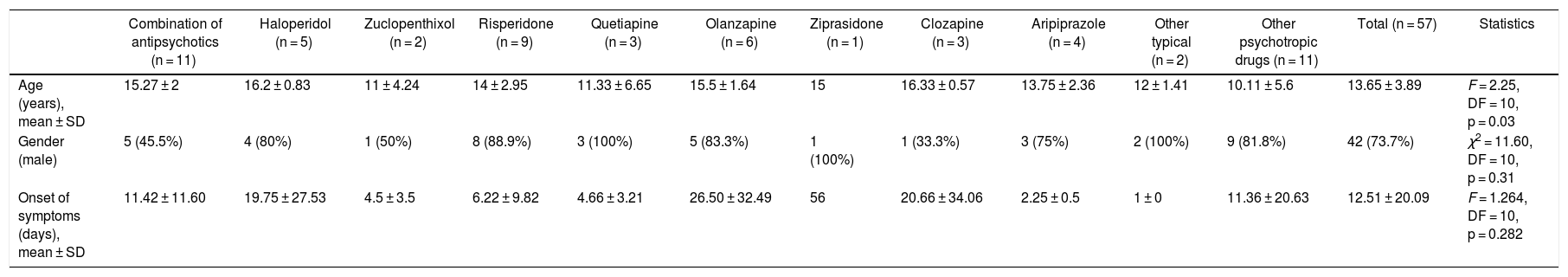

The sample included 57 patients (42 men and 15 women), with an average age of 13.65 ± 3.89 years. The most frequent diagnosis was acute psychotic disorder (21.1%) (Table 1). The onset of NMS occurred at 11.25 ± 20.27 days when only typical antipsychotics were used (n = 8) and at 13.69 ± 22.43 days when atypical antipsychotics were used (n = 26) (Table 2).

Age, gender and diagnosis of 57 patients under 18 years of age with neuroleptic malignant syndrome reported between 2005 and 2018.

| Characteristic | N. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD (range) | 13.65 ± 3.89 (0.3–17) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 42 (73.7) |

| Female | 15 (26.3) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Schizophrenia | 4 (7) |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 9 (15.8) |

| Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) | 4 (7) |

| Pervasive developmental disorder | 3 (5.3) |

| Organic mental illness | 10 (17.5) |

| Mental retardation | 2 (3.5) |

| Acute psychotic disorder | 12 (21.1) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 5 (8.8) |

| Other | 8 (14) |

SD: standard deviation.

Cases of NMS caused by antipsychotics and other psychotropic drugs in 57 patients under 18 years of age.

| Combination of antipsychotics (n = 11) | Haloperidol (n = 5) | Zuclopenthixol (n = 2) | Risperidone (n = 9) | Quetiapine (n = 3) | Olanzapine (n = 6) | Ziprasidone (n = 1) | Clozapine (n = 3) | Aripiprazole (n = 4) | Other typical (n = 2) | Other psychotropic drugs (n = 11) | Total (n = 57) | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 15.27 ± 2 | 16.2 ± 0.83 | 11 ± 4.24 | 14 ± 2.95 | 11.33 ± 6.65 | 15.5 ± 1.64 | 15 | 16.33 ± 0.57 | 13.75 ± 2.36 | 12 ± 1.41 | 10.11 ± 5.6 | 13.65 ± 3.89 | F = 2.25, DF = 10, p = 0.03 |

| Gender (male) | 5 (45.5%) | 4 (80%) | 1 (50%) | 8 (88.9%) | 3 (100%) | 5 (83.3%) | 1 (100%) | 1 (33.3%) | 3 (75%) | 2 (100%) | 9 (81.8%) | 42 (73.7%) | χ2 = 11.60, DF = 10, p = 0.31 |

| Onset of symptoms (days), mean ± SD | 11.42 ± 11.60 | 19.75 ± 27.53 | 4.5 ± 3.5 | 6.22 ± 9.82 | 4.66 ± 3.21 | 26.50 ± 32.49 | 56 | 20.66 ± 34.06 | 2.25 ± 0.5 | 1 ± 0 | 11.36 ± 20.63 | 12.51 ± 20.09 | F = 1.264, DF = 10, p = 0.282 |

SD: standard deviation; DF: degrees of freedom.

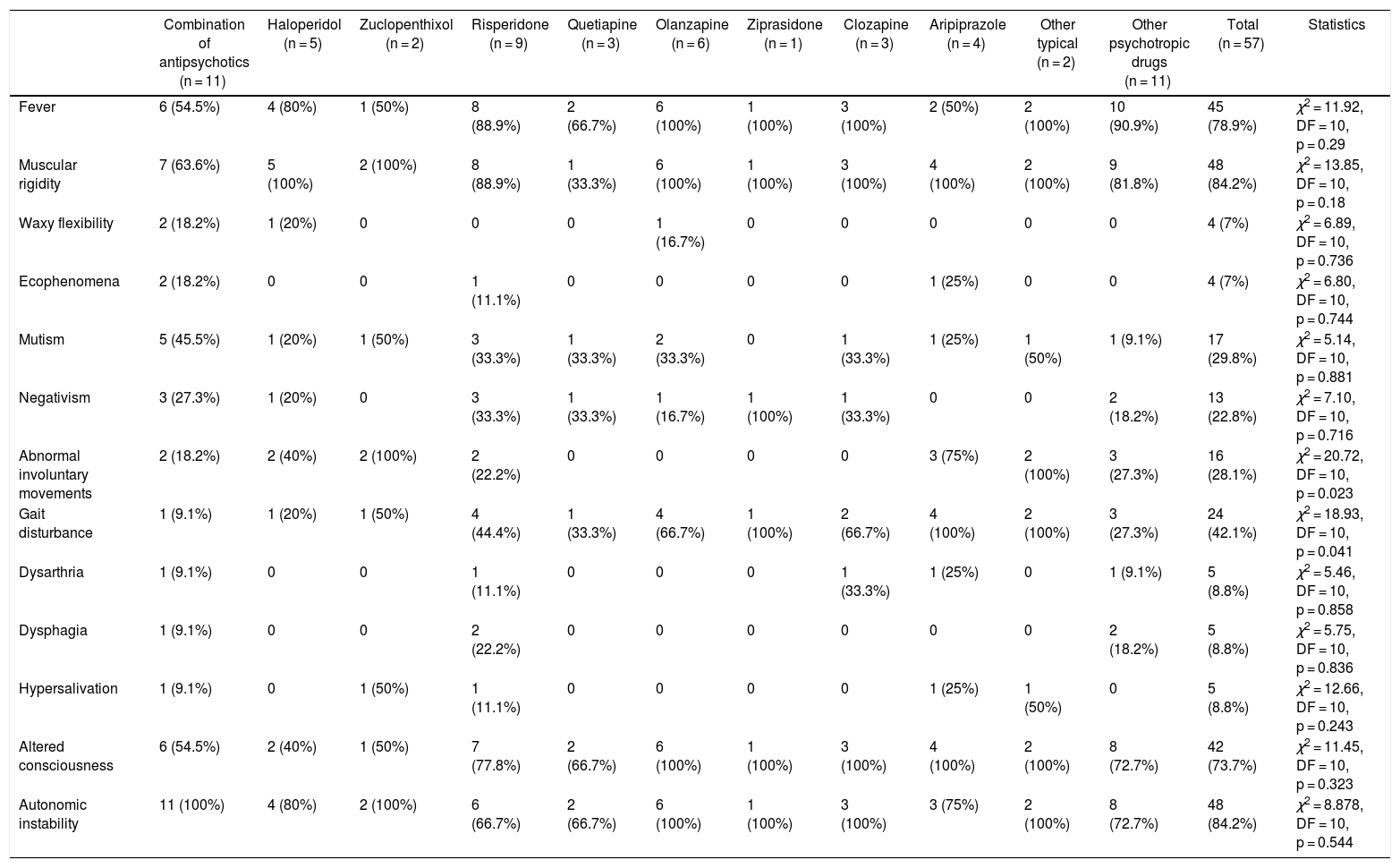

Table 3 shows the frequency of clinical symptoms by antipsychotic. The most frequent symptoms were muscle rigidity (84.2%), autonomic instability (84.2%) and fever (78.9%). The clinical presentation of NMS differed depending on the antipsychotic used, with Abnormal involuntary movements (p = 0.023) and gait disturbance (p = 0.023) being those related to the antipsychotic administered. Fever was observed in all cases in which olanzapine, ziprasidone and clozapine were administered. However, these differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.29). We found no fatal cases.

Frequency of symptoms of 57 cases of patients under 18 years of age with antipsychotic-induced NMS.

| Combination of antipsychotics (n = 11) | Haloperidol (n = 5) | Zuclopenthixol (n = 2) | Risperidone (n = 9) | Quetiapine (n = 3) | Olanzapine (n = 6) | Ziprasidone (n = 1) | Clozapine (n = 3) | Aripiprazole (n = 4) | Other typical (n = 2) | Other psychotropic drugs (n = 11) | Total (n = 57) | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever | 6 (54.5%) | 4 (80%) | 1 (50%) | 8 (88.9%) | 2 (66.7%) | 6 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 2 (50%) | 2 (100%) | 10 (90.9%) | 45 (78.9%) | χ2 = 11.92, DF = 10, p = 0.29 |

| Muscular rigidity | 7 (63.6%) | 5 (100%) | 2 (100%) | 8 (88.9%) | 1 (33.3%) | 6 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 2 (100%) | 9 (81.8%) | 48 (84.2%) | χ2 = 13.85, DF = 10, p = 0.18 |

| Waxy flexibility | 2 (18.2%) | 1 (20%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (7%) | χ2 = 6.89, DF = 10, p = 0.736 |

| Ecophenomena | 2 (18.2%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (25%) | 0 | 0 | 4 (7%) | χ2 = 6.80, DF = 10, p = 0.744 |

| Mutism | 5 (45.5%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (50%) | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (25%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (9.1%) | 17 (29.8%) | χ2 = 5.14, DF = 10, p = 0.881 |

| Negativism | 3 (27.3%) | 1 (20%) | 0 | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (100%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (18.2%) | 13 (22.8%) | χ2 = 7.10, DF = 10, p = 0.716 |

| Abnormal involuntary movements | 2 (18.2%) | 2 (40%) | 2 (100%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (75%) | 2 (100%) | 3 (27.3%) | 16 (28.1%) | χ2 = 20.72, DF = 10, p = 0.023 |

| Gait disturbance | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (50%) | 4 (44.4%) | 1 (33.3%) | 4 (66.7%) | 1 (100%) | 2 (66.7%) | 4 (100%) | 2 (100%) | 3 (27.3%) | 24 (42.1%) | χ2 = 18.93, DF = 10, p = 0.041 |

| Dysarthria | 1 (9.1%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (25%) | 0 | 1 (9.1%) | 5 (8.8%) | χ2 = 5.46, DF = 10, p = 0.858 |

| Dysphagia | 1 (9.1%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (18.2%) | 5 (8.8%) | χ2 = 5.75, DF = 10, p = 0.836 |

| Hypersalivation | 1 (9.1%) | 0 | 1 (50%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (25%) | 1 (50%) | 0 | 5 (8.8%) | χ2 = 12.66, DF = 10, p = 0.243 |

| Altered consciousness | 6 (54.5%) | 2 (40%) | 1 (50%) | 7 (77.8%) | 2 (66.7%) | 6 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 2 (100%) | 8 (72.7%) | 42 (73.7%) | χ2 = 11.45, DF = 10, p = 0.323 |

| Autonomic instability | 11 (100%) | 4 (80%) | 2 (100%) | 6 (66.7%) | 2 (66.7%) | 6 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 3 (75%) | 2 (100%) | 8 (72.7%) | 48 (84.2%) | χ2 = 8.878, DF = 10, p = 0.544 |

DF: degrees of freedom.

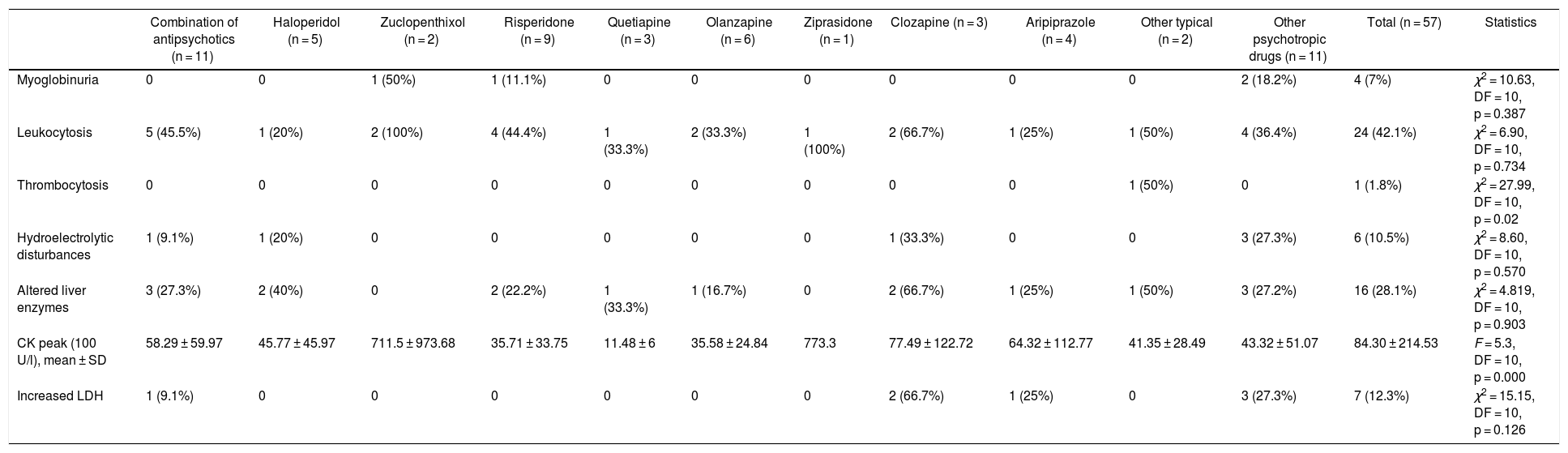

Table 4 presents the main laboratory findings by antipsychotic drug. The mean CK (100 IU/l) was 84.30 ± 214.53. In men, we found a mean CK of 96.64 ± 248.72, while in women it was 52.20 ± 69.22. However, these differences were not significant (p = 0.314). The most frequent laboratory finding, after elevated CK, was leukocytosis (42.1%).

Laboratory tests of 57 cases of patients under 18 years of age with antipsychotic-induced NMS.

| Combination of antipsychotics (n = 11) | Haloperidol (n = 5) | Zuclopenthixol (n = 2) | Risperidone (n = 9) | Quetiapine (n = 3) | Olanzapine (n = 6) | Ziprasidone (n = 1) | Clozapine (n = 3) | Aripiprazole (n = 4) | Other typical (n = 2) | Other psychotropic drugs (n = 11) | Total (n = 57) | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myoglobinuria | 0 | 0 | 1 (50%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (18.2%) | 4 (7%) | χ2 = 10.63, DF = 10, p = 0.387 |

| Leukocytosis | 5 (45.5%) | 1 (20%) | 2 (100%) | 4 (44.4%) | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 1 (100%) | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (25%) | 1 (50%) | 4 (36.4%) | 24 (42.1%) | χ2 = 6.90, DF = 10, p = 0.734 |

| Thrombocytosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (50%) | 0 | 1 (1.8%) | χ2 = 27.99, DF = 10, p = 0.02 |

| Hydroelectrolytic disturbances | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (20%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 0 | 3 (27.3%) | 6 (10.5%) | χ2 = 8.60, DF = 10, p = 0.570 |

| Altered liver enzymes | 3 (27.3%) | 2 (40%) | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (25%) | 1 (50%) | 3 (27.2%) | 16 (28.1%) | χ2 = 4.819, DF = 10, p = 0.903 |

| CK peak (100 U/l), mean ± SD | 58.29 ± 59.97 | 45.77 ± 45.97 | 711.5 ± 973.68 | 35.71 ± 33.75 | 11.48 ± 6 | 35.58 ± 24.84 | 773.3 | 77.49 ± 122.72 | 64.32 ± 112.77 | 41.35 ± 28.49 | 43.32 ± 51.07 | 84.30 ± 214.53 | F = 5.3, DF = 10, p = 0.000 |

| Increased LDH | 1 (9.1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (25%) | 0 | 3 (27.3%) | 7 (12.3%) | χ2 = 15.15, DF = 10, p = 0.126 |

CK: creatine kinase; DF: degrees of freedom; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; SD: standard deviation.

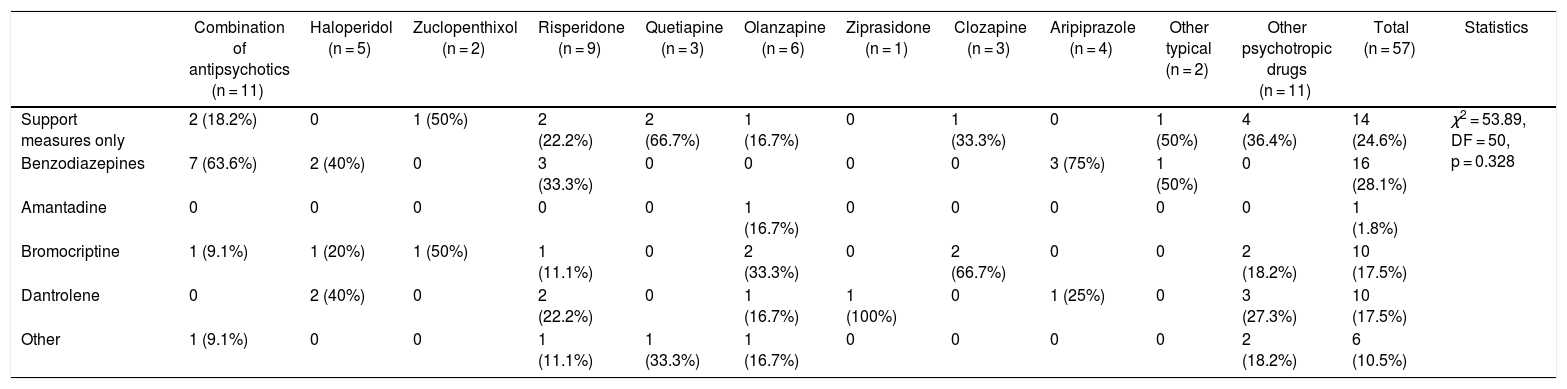

Table 5 shows the different NMS treatments used in the study sample, the most frequent one being benzodiazepines (28.1%) followed by supportive measures (24.6%).

Management of 57 cases of patients under 18 years of age with antipsychotic-induced NMS.

| Combination of antipsychotics (n = 11) | Haloperidol (n = 5) | Zuclopenthixol (n = 2) | Risperidone (n = 9) | Quetiapine (n = 3) | Olanzapine (n = 6) | Ziprasidone (n = 1) | Clozapine (n = 3) | Aripiprazole (n = 4) | Other typical (n = 2) | Other psychotropic drugs (n = 11) | Total (n = 57) | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support measures only | 2 (18.2%) | 0 | 1 (50%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 1 (50%) | 4 (36.4%) | 14 (24.6%) | χ2 = 53.89, DF = 50, p = 0.328 |

| Benzodiazepines | 7 (63.6%) | 2 (40%) | 0 | 3 (33.3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (75%) | 1 (50%) | 0 | 16 (28.1%) | |

| Amantadine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.8%) | |

| Bromocriptine | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 2 (33.3%) | 0 | 2 (66.7%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (18.2%) | 10 (17.5%) | |

| Dantrolene | 0 | 2 (40%) | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (100%) | 0 | 1 (25%) | 0 | 3 (27.3%) | 10 (17.5%) | |

| Other | 1 (9.1%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (18.2%) | 6 (10.5%) |

DF: degrees of freedom.

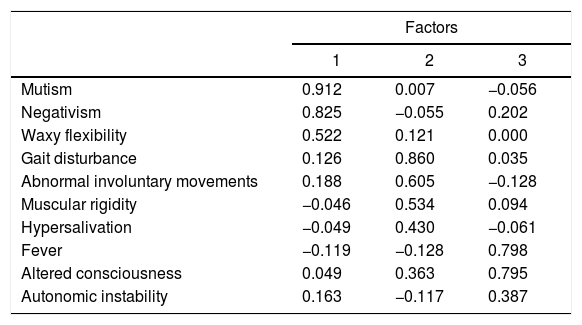

The feasibility tests to perform the factor analysis were satisfactory (Bartlett’s sphericity test: χ2 = 114.92, p = 0.004; KMO value = 0.555). Symptoms are reduced when grouped into three factors: 1) “catatonic” (eigenvalue 1.884, with a variance of 18.837%); 2) “extrapyramidal syndrome” (eigenvalue 1.755, with a variance of 17.54%), and 3) “autonomic instability” (eigenvalue 1.493, with a variance of 14.92%). Table 6 shows the grouping of symptoms in the three factors.

Exploratory factor analysis of the symptoms of 57 cases of patients under 18 years of age with NMS.

| Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Mutism | 0.912 | 0.007 | −0.056 |

| Negativism | 0.825 | −0.055 | 0.202 |

| Waxy flexibility | 0.522 | 0.121 | 0.000 |

| Gait disturbance | 0.126 | 0.860 | 0.035 |

| Abnormal involuntary movements | 0.188 | 0.605 | −0.128 |

| Muscular rigidity | −0.046 | 0.534 | 0.094 |

| Hypersalivation | −0.049 | 0.430 | −0.061 |

| Fever | −0.119 | −0.128 | 0.798 |

| Altered consciousness | 0.049 | 0.363 | 0.795 |

| Autonomic instability | 0.163 | −0.117 | 0.387 |

Extraction method: principal component analysis. Varimax rotated solution with Kaiser normalisation.

Factor 1: catatonic; factor 2: extrapyramidal; factor 3: autonomically unstable.

The current state of knowledge of NMS is based on case reports and series, few of which were carried out in children and adolescents. This study found that more cases were reported in males, similarly to Silva et al.,2 who found a higher frequency of NMS in males (63.63%) in case reports of children and adolescents. This is probably due to this population being more frequently exposed to antipsychotics, since many of the diseases in child and adolescent psychiatry predominantly affect males.65

The onset of symptoms occurred at 11.25 ± 20.27 days when only typical antipsychotics were used, and at 13.69 ± 22.43 days when atypical antipsychotics were used. However, this difference is not significant. In the literature, it has been reported that the time to the onset of symptoms was 8.7 ± 16.2 days in a sample of child–adolescent patients who developed NMS after the administration of atypical antipsychotics.66 These differences could be explained by the different sample sizes. These results are similar to those described in the adult population; as reported by Caroff and Mann,67 16% of patients develop NMS symptoms within the first 24 h, 66% within the first week, and 96% within a month. The clinical implications of this result suggest that we should maintain a watchful eye for the appearance of NMS symptoms for around two weeks.

The most frequently reported symptoms were: muscle rigidity, autonomic instability, fever and altered consciousness. These results are similar to those reported in other studies in a child–adolescent population exposed to typical and atypical antipsychotics,2 as well as to only atypical ones,66 Catatonic symptoms were also found, such as mutism and negativism, among others, which have been described in the literature since the 1980s. However, since then, more importance has been given to systemic than to catatonic manifestations.68 Some authors view malignant catatonia and NMS as two different conditions with overlapping clinical characteristics, while for others they are the same disorder.68 The appearance of catatonic symptoms in the adult population has been associated with greater severity and worse prognosis. This association is not entirely clear in the child–adolescent population.69,70

Abnormal involuntary movements were found more frequently in patients who received typical antipsychotics, with these differences being statistically significant. This was an expected finding, since dopamine blockade in the nigrostriatal pathway, caused by typical antipsychotics, tends to cause such clinical manifestations. Although dopamine blockade at the hypothalamus level would explain the autonomic alteration as well as thermoregulation, we found that these findings were not related to any particular antipsychotic.5

The main treatment used for NMS cases in our sample was benzodiazepines, followed by the exclusive use of life support measures. These results are different from that reported in another review, which found that the use of dantrolene was greater than that of benzodiazepines (39% vs. 30%).66 A possible explanation for this difference could be that the cases in our study were less severe, not requiring the use of dantrolene, which is reserved for severe cases of NMS This could be explained by the fact that in the last two decades greater care has been taken when titrating antipsychotics in children and adolescents.4

ECT is little used in the child–adolescent population,71 which would explain why it is the least used therapeutic measure in our sample. ECT can be considered as a second-line treatment, administered if the supportive measures and pharmacological treatment fail during the first seven days. Furthermore, it is used in those cases in which the underlying psychiatric diagnosis is psychotic depression or catatonia, which differs from the diagnoses of the cases that were reviewed in this study.72

In the factor analysis of symptoms, we found three factors: factor 1 (catatonia), factor 2 (extrapyramidal) and factor 3 (autonomic instability). In catatonic NMS, we found patients with a predominance of catatonic symptoms, which would partly explain the overlap between NMS and lethal catatonia. In extrapyramidal NMS, the predominance occurs in the usual extrapyramidal adverse reactions, while in autonomically unstable NMS there is a greater grouping of systemic symptoms. These findings could have therapeutic implications, with ECT and benzodiazepines being the treatment in NMS with catatonic predominance, bromocriptine or dantrolene used in extrapyramidal syndrome, and support measures used in autonomic instability.

This study’s potential limitations must be taken into consideration. The main one is related to the low representation and the small number of reported cases, which is because we analysed uncontrolled secondary sources. A systematic review of case reports cannot provide strong associations. However, it could report some hypotheses for later studies. Furthermore, we must emphasise that any attempt to apply the scientific method rigorously to the study of NMS must face the intrinsic challenges of this condition: it is unpredictable and appears infrequently, it has no established clinical markers and, often, it presents as an emerging disorder that threatens the life of the patient, making it difficult to obtain informed consent to participate in research protocols.

ConclusionsNMS in this sample was more frequent in males. The most frequently reported symptoms were: muscle rigidity, autonomic instability and fever. According to the factor analysis of symptoms, NMS could be of three types: catatonic, extrapyramidal and autonomically unstable.

FundingSelf-financed.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: León-Amenero D, Huarcaya-Victoria J. Síndrome neuroléptico maligno en niños y adolescentes: revisión sistemática de reportes de caso. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:290–300.