Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) can interfere with academic and professional performance, as affected individuals tend to fall asleep in situations that demand a high level of alertness. Medical students are often a population at risk of suffering from EDS due to the demanding number of study hours, the significant number of credits per subject in the academic curriculum, practical teaching sessions and hospital night shifts, which can lead to sleep deprivation or sleep debt. It is for these reasons that it is important to estimate the prevalence of EDS and its associated factors in medical students of a Higher Education Institution (HEI) in Bucaramanga, in order to implement early prevention strategies to reduce the occurrence of this problem and to improve the students’ quality of life and academic performance.

Material and methodsAn observational, cross-sectional analytical study with a population sample of 458 medical students enrolled in the second semester of 2015 at the Universidad Autonoma de Bucaramanga (UNAB), who completed four questionnaires: Sociodemographic Variables, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and Sleep Hygiene Index (SHI). A bivariate and multivariate analysis was performed to identify any correlations with EDS.

ResultsMean student age was 20.3 years and 62.88% of the 458 respondents were women. We were able to establish that 80.75% of participants suffered from EDS and 80.55% had a negative perception of their sleep quality (OR=1.91; 95% CI, 1.11–3.29; p=0.019]. In the multivariate analysis, it was found that the risk of EDS is lower in the clinical sciences than in the basic cycle. Furthermore, it was noted that a score higher than 15 in the Sleep Hygiene Index significantly increases the risk of suffering from EDS.

ConclusionsAlthough EDS is very common in medical students, only a small percentage present the most severe form of this sleep disorder. Being enrolled in basic cycle subjects is associated with a higher risk of suffering EDS, so it is important for the curriculum committees of higher education institutions to regularly evaluate the number of hours of supervised and independent work performed by medical students. Finally, it is important to implement campaigns aimed at improving university students’ perception of the risk of taking energy drinks and to establish sleep hygiene recommendations from the start of the academic programme.

La somnolencia diurna excesiva (SDE) puede llegar a interferir en el desempeño académico y profesional, debido a que las personas afectadas tienden a quedarse dormidas en situaciones que exigen un alto nivel de atención. Los estudiantes de Medicina representan una población en riesgo de SDE, dada la exigencia académica de numerosas horas de estudio, debido al gran número de créditos por asignatura contenidos en el plan de estudios del programa académico, las prácticas docentes asistenciales y los turnos nocturnos, que pueden generar privación o déficit acumulado del sueño. Por esta razón, es importante estimar la prevalencia de SDE y los factores asociados en estudiantes de Medicina de una institución de educación superior (IES) de Bucaramanga, con el objetivo de implementar estrategias de prevención primaria que disminuyan la presentación de este problema y mejoren la calidad de vida y el desempeño académico de los estudiantes.

Material y métodosEstudio transversal analítico observacional, con una muestra poblacional de 458 estudiantes de Medicina matriculados en el segundo semestre de 2015 en la Universidad Autónoma de Bucaramanga (UNAB), quienes respondieron a 4 cuestionarios: variables sociodemográficas, escala de somnolencia de Epworth, índice de calidad del sueño de Pittsburg (ICSP) e índice de higiene del sueño (IHS). Se realizó el análisis bivariable y multivariable en busca de asociación con SDE.

ResultadosLos estudiantes tenían una media de edad de 20,3 años; de los 458 encuestados, el 62,88% eran mujeres. Se estableció que el 80,75% de los participantes tenían SDE y el 80,55%, una percepción negativa de la calidad del sueño (OR = 1,91;IC95%, 1,11-3,29; p = 0,019). En el análisis multivariable, se encontró que el hecho de estar cursando ciencias clínicas disminuye el riesgo de SDE respecto a quienes estaban cursando el ciclo básico. Además, se observó que una puntuación > 15 en el IHS aumenta de manera significativa el riesgo de padecer SDE.

ConclusionesAunque es frecuente encontrar SDE en los estudiantes de Medicina, solo un pequeño porcentaje de ellos sufren la forma severa de este trastorno del sueño. Estar cursando asignaturas del ciclo básico se asocia con mayor riesgo de SDE, por lo cual es importante que los comités curriculares de las IES evalúen regularmente la cantidad de horas de trabajo supervisado e independiente que realizan los estudiantes de Medicina. Finalmente, es importante emprender campañas orientadas a mejorar la percepción de riesgo sobre el uso de bebidas energizantes de los estudiantes universitarios y realizar, desde el ingreso al programa académico, recomendaciones sobre los hábitos de higiene del sueño.

Sleep is one of the most important human behaviours and it takes up a third of people's lives, with important functions in homeostasis and consolidation of mnesic traces.1 However, due to the increase in modern world activities, which require greater performance and more competitive professionals in the labour market, the sleep-wake cycle of individuals has been affected, which brings as a consequence an increase in the frequency of mental health problems, greater use of substances (psychoactive substances, energy drinks, products containing caffeine and wakefulness-promoting drugs)2 and an increase in the risk of accidents3; it is estimated that around 30% of road traffic accidents are due to sleepiness.4

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), sleep disorders are classified into insomnia, hypersomnia, narcolepsy, parasomnias, breathing-related sleep disorders and other non-specified sleep-wake disorders.5 These sleep disorders are common and represent one of the most prevalent health problems, as they affect more than one third of the general population.6,7 In Colombia, the SUECA study, carried out in 2008 in the municipalities of Manizales, Villamaría and Neira, with a sample of 787 people over the age of seven, estimated a general prevalence of insomnia of 47.20% and of hypersomnia of 20.90% in the study population.8

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is defined as the tendency to fall asleep in situations which require a high degree of attentiveness4 and, despite being a prevalent condition in almost all stages of the life cycle,9 it can occur in one in five adults10 and be associated with alterations in metabolic markers. However, it has been little studied and health services tend to ignore it.4

The causes of EDS can be primary or secondary.11 Among the primary causes are narcolepsy, idiopathic hypersomnia and other rare hypersomnias (Kleine-Levin syndrome). The secondary causes are sub-divided into three groups: disorders which occur during sleep or are related to sleep (type of job, jet lag, restless legs syndrome and various situations which alter the circadian rhythm), those associated with medical conditions (traumatic brain injury, stroke, cancer, neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases) and, thirdly, the effects of certain medicines, such as hypnotics or benzodiazepines. With the sociocultural changes of modern life, new variables have also emerged which lead to voluntary and involuntary sleep deprivation and promote EDS.1,4,12

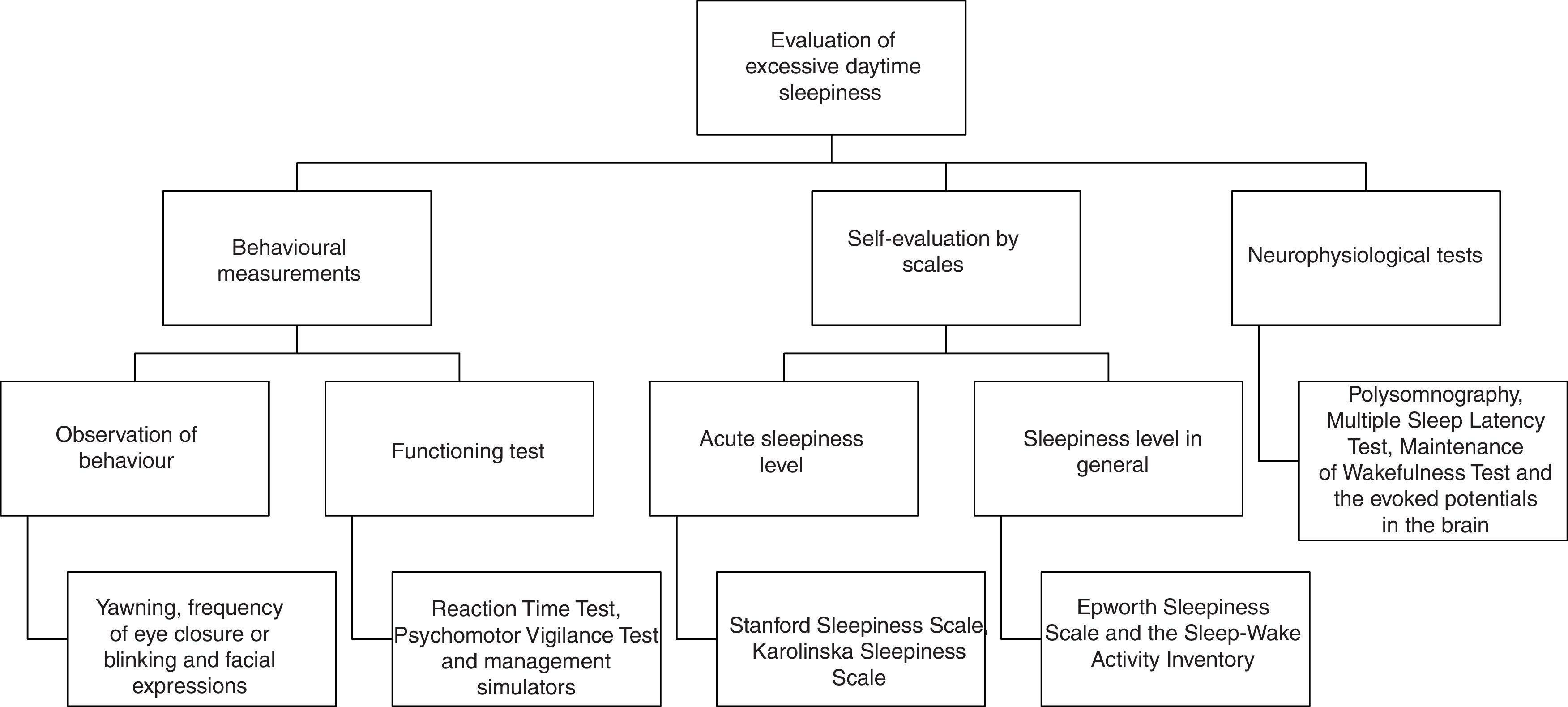

EDS is assessed using different methods; its measurement is complex and the combination of different tests and a complete medical history is required.1 The instrument which is used most frequently in the diagnostic approach is the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, which has good psychometric properties and has proven capacity to differentiate between individuals with and without the disorder. The diagnosis tends to be complemented with information from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, which evaluates the general quality of sleep and its disturbances during the previous month2,13,14 (Fig. 1).

University students, in particular those who study highly academically-demanding programmes, are a group of interest in terms of the presence of sleep disorders, as it is a population group mainly made up of young adults who go to bed very late and, therefore, have fewer hours of sleep, which also tend to be fragmented, generating EDS with probable physical and intellectual consequences.15 In the specific case of Medicine undergraduate education, mastering the necessary skills for a professional career involves students undertaking a large number of academic activities which are both theoretical and practical, as well as provide care during the clinical cycle. All this requires effort and time not only during the day, but often during the night, leading to chronic sleep deprivation and an accumulated deficit.4

As shown by several studies carried out in different parts of the world, a high percentage of undergraduate and postgraduate medical students suffer from EDS. A study carried out in Malaysia revealed that 35.50% of undergraduate medical students suffer from EDS associated with poor sleep quality.16 Another investigation carried out in Israel applied the Epworth scale to a sample of undergraduate students in the fifth and sixth year of Medicine and compared it with another sample of postgraduate students. The results revealed that the latter group had a greater risk of falling asleep (from five to eight times a day) during healthcare activities and having road traffic accidents; in addition, 63% of them had worse professional performance after night shifts.17 In Brazil, an EDS prevalence of 42.40% was reported and a major association with psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety was established.18

Various studies have been carried out in Colombia. Two carried out at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia [National University of Colombia] (UNAL) showed a high prevalence of EDS, which affected more than half of the students in the third and ninth semester, with a prevalence of 59.60%19 and 60.24%,9 respectively. In addition, it was demonstrated that poor sleep hygiene and the negative perception of sleep quality were greater in students who did more night shifts.9 Another study carried out at the Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira [Technological University of Pereira] (UTP) reported an EDS prevalence of 49.80% in medical students.13

The highly demanding hours of study leads to the need to stay awake for longer and to the consequent reduction in the hours of sleep.20 In addition, with the aim of improving semantic memory performance, logical reasoning and free recall memory, an increase in the consumption of caffeine, energy drinks, alcohol, nicotine and psychostimulant drugs has been found, which influence the amount and quality of sleep.15,21–23

Consuming substances containing caffeine in their primary composition (coffee, energy drinks) generates effects on sleep, such as reduced total sleep time, increased latency and reduced percentages of stages three and four of sleep without rapid eye movement.21,22 Their concomitant use with alcohol or nicotine can cause profound insomnia and fragmentation of sleep, which are expressed as EDS due to the different half-lives and opposing pharmacological actions of these substances.15,24 The use of central nervous system stimulants (modafinil, methylphenidate) is currently on the rise among young students and it has been reported that up to 15% of the Latin American population uses them.25 Their use has been related to the search for effects such as increased alertness and physical performance, acceleration of psychic processes and reduced fatigue; however, the consumption of these drugs has also been associated with reduced total restful sleep time, expressed as EDS.26

The consequences of suffering from EDS can be severe and have been associated with alterations in daily functionality,27 low work productivity, road traffic accidents,28 risky behaviours and impaired academic performance.29 Given that no study which addresses EDS in medical students in Bucaramanga and its metropolitan area has been found, it is considered important to estimate the prevalence of this condition and to analyse the associated factors, taking into account that it is a vulnerable population which would benefit from primary prevention programmes that could be implemented on the basis provided by this research.

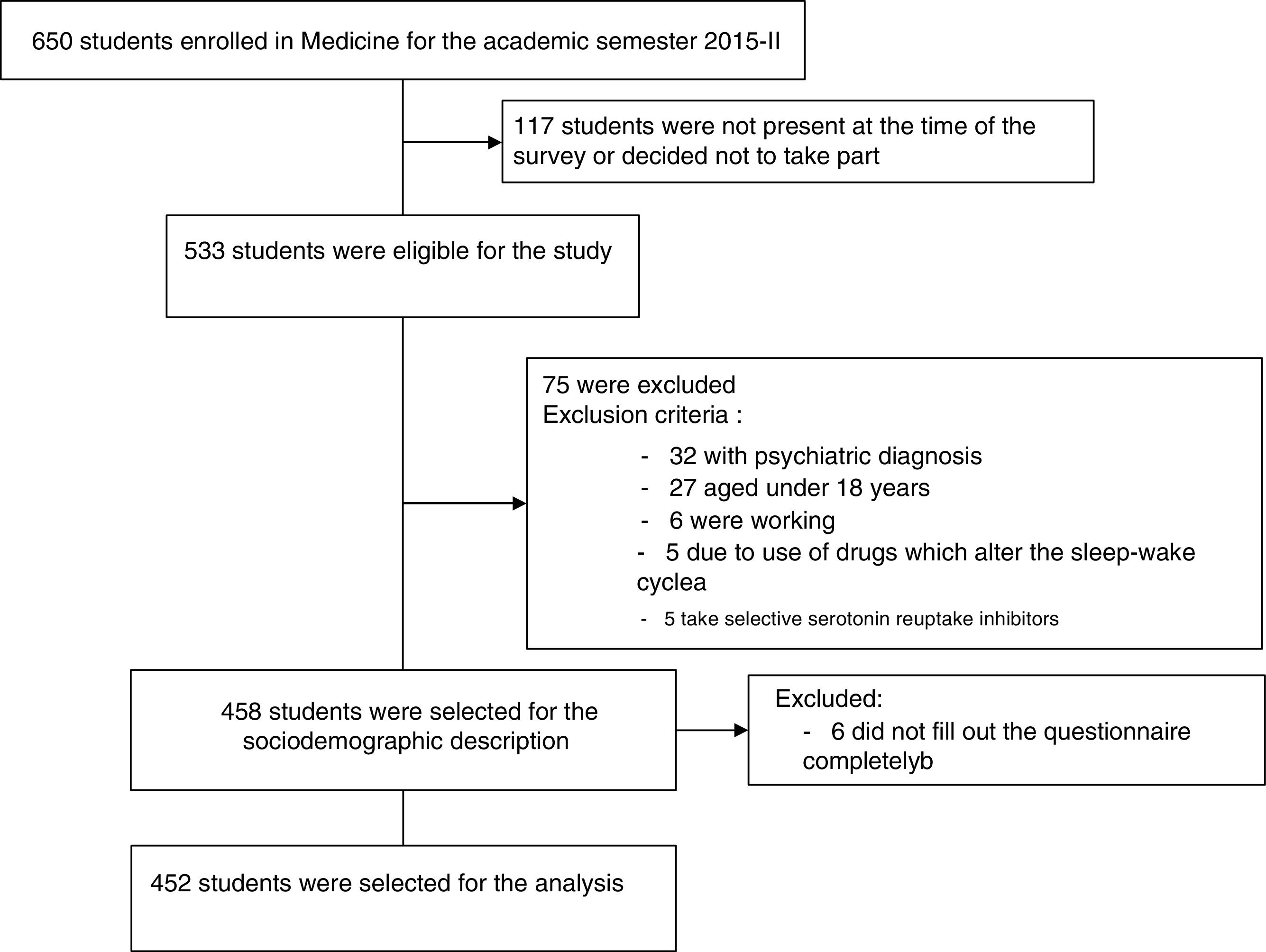

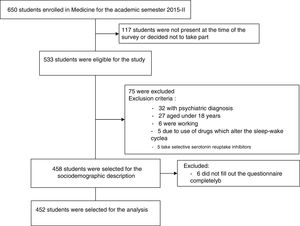

Material and methodsA cross-sectional analytical observational study in medical students at the Universidad Autónoma de Bucaramanga [Autonomous University of Bucaramanga], approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the UNAB (IREC), was conducted. The target population of the study was made up of 458 medical students who fulfilled the inclusion criteria: being over the age of 18 and being enrolled in the second academic period of 2015 in the different course subjects between the second and tenth semester of the study plan. Students with a diagnosis of a mental disorder or who were on treatments with medicines prescribed by a doctor that could affect the sleep-wake cycle, as well as students who said they were also working during their academic semester, were excluded. Furthermore, for the bivariate and multivariate analyses, six participants were excluded for not having completely filled in one of the sleep evaluation instruments. Therefore, 458 students were included for the description of the sociodemographic variables and of substance use, and 452 for the statistical analyses (Fig. 2).

Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Permission of the teaching staff was granted for the authors to take the information at the start of the lectures that grouped the largest number of students enrolled in each academic semester; the instruments were applied in week 13 of the academic calendar, a period with no general assessments (duration of the academic semester: 20 weeks). Verbal informed consent was obtained from all the participants, taking into account that it was minimal risk study based on Resolution no. 008430 of 1993. Subsequently, a single and self-administered questionnaire was given out with 49 questions, which included the following measuring instruments: sociodemographic characteristics, substance use variables (caffeine, alcohol, cigarettes, energy drinks, wakefulness-promoting drugs) and habits associated with EDS (12 questions), the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (8 questions) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (19 questions) validated in the Colombian population, and the Sleep Hygiene Index (10 questions) validated in Peru, which are described below.

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale is a self-administered questionnaire which evaluates the tendency to fall asleep in eight different sedentary situations and generates from 0 to 24 points; scores>10 indicate EDS (between 8 and 9 points indicate mild daytime sleepiness; between 10 and 15 points moderate daytime sleepiness, and >16 points severe daytime sleepiness).19 Internal consistency in its Colombian version is a Cronbach's alpha=0.85, with criterion validity to differentiate the different degrees of sleepiness and the detection of real sleep disorders confirmed by polysomnography.30

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index is a self-administered instrument which evaluates the quality of sleep and its disturbances during the last month in clinical and non-clinical populations, from 0 to 21 points; scores>5 indicate poor sleep quality (5–7 points require medical attention; 8–14 points require medical attention and medical treatment, and >15 points describe a severe sleep problem).31 Internal consistency in its Colombian version presents α=0.78, and it is an adequate instrument for the evaluation of sleep disorders which identifies “good and bad” sleepers.32

The Sleep Hygiene Index is a self-administered instrument that evaluates the presence of behaviours which disrupt sleep hygiene and classifies their frequency of presentation (always, frequently, sometimes, rarely, never). The scores from each component are added up and the total evaluation is obtained (0–65 points). A higher score indicates worse sleep hygiene.33,34 Its internal validity in its version for the Latin American population reflects α=0.70, which enables early detection of factors that alter sleep hygiene and makes it possible to make proposals to treat them.34

Once the questionnaires had been filled in anonymously, each student placed them in a sealed ballot box, which was located at the front of the auditorium. Then the data were incorporated into a Microsoft Excel matrix and the statistical analysis was performed with the STATA 13® software, with a descriptive analysis by means of measures of central tendency and dispersion of quantitative variables, in addition to proportions with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the qualitative variables. A multivariate analysis was carried out with a logistic regression model to calculate crude odds ratios (OR) and adjusted odds ratios (ORa) with their respective 95% CI for the variables that fulfilled statistical and epidemiological criteria and that merited their inclusion in the model, following stratified analysis. The variables included in the final model fulfilled the Greenland criteria and the principle of parsimony; Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit tests and analysis of influence and co-linearity were carried out to determine the most efficient explanatory model.35 For all the statistical tests, a significance level of α=0.05 was applied.

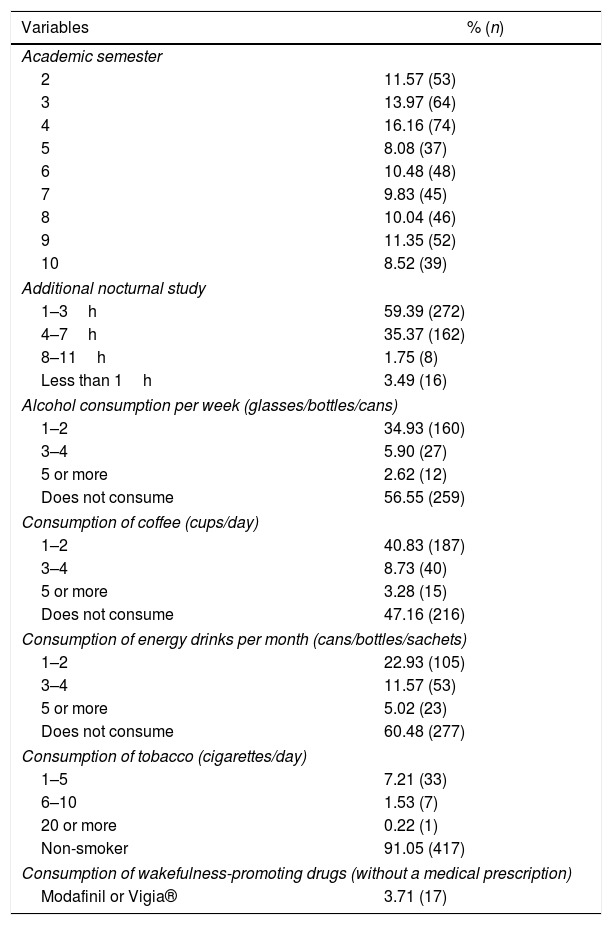

ResultsA total of 458 students were evaluated, and 452 were analysed in relation to the sleep variable. The mean age of the entire population was 20.30 (18–34) years; 62.88% (288/458) were female. In terms of the level of academic education, 41.70% (n=191) were studying the basic sciences semester (second to fourth semester) and 58.30% (n=267) were studying the clinical sciences semester (fifth to tenth semester); in relation to night shifts, 50.44% (n=231) reported that they were doing them (clinical sciences, the fifth semester was excluded because they did shifts of fewer than 4h per month). With regards to the consumption of wakefulness-promoting substances, 52.84% reported drinking coffee and 39.52% energy drinks. The sociodemographic characteristics and characteristics of consumption of wakefulness-promoting substances are described in Table 1.

Sociodemographic description and categorisation of the main variables.

| Variables | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Academic semester | |

| 2 | 11.57 (53) |

| 3 | 13.97 (64) |

| 4 | 16.16 (74) |

| 5 | 8.08 (37) |

| 6 | 10.48 (48) |

| 7 | 9.83 (45) |

| 8 | 10.04 (46) |

| 9 | 11.35 (52) |

| 10 | 8.52 (39) |

| Additional nocturnal study | |

| 1–3h | 59.39 (272) |

| 4–7h | 35.37 (162) |

| 8–11h | 1.75 (8) |

| Less than 1h | 3.49 (16) |

| Alcohol consumption per week (glasses/bottles/cans) | |

| 1–2 | 34.93 (160) |

| 3–4 | 5.90 (27) |

| 5 or more | 2.62 (12) |

| Does not consume | 56.55 (259) |

| Consumption of coffee (cups/day) | |

| 1–2 | 40.83 (187) |

| 3–4 | 8.73 (40) |

| 5 or more | 3.28 (15) |

| Does not consume | 47.16 (216) |

| Consumption of energy drinks per month (cans/bottles/sachets) | |

| 1–2 | 22.93 (105) |

| 3–4 | 11.57 (53) |

| 5 or more | 5.02 (23) |

| Does not consume | 60.48 (277) |

| Consumption of tobacco (cigarettes/day) | |

| 1–5 | 7.21 (33) |

| 6–10 | 1.53 (7) |

| 20 or more | 0.22 (1) |

| Non-smoker | 91.05 (417) |

| Consumption of wakefulness-promoting drugs (without a medical prescription) | |

| Modafinil or Vigia® | 3.71 (17) |

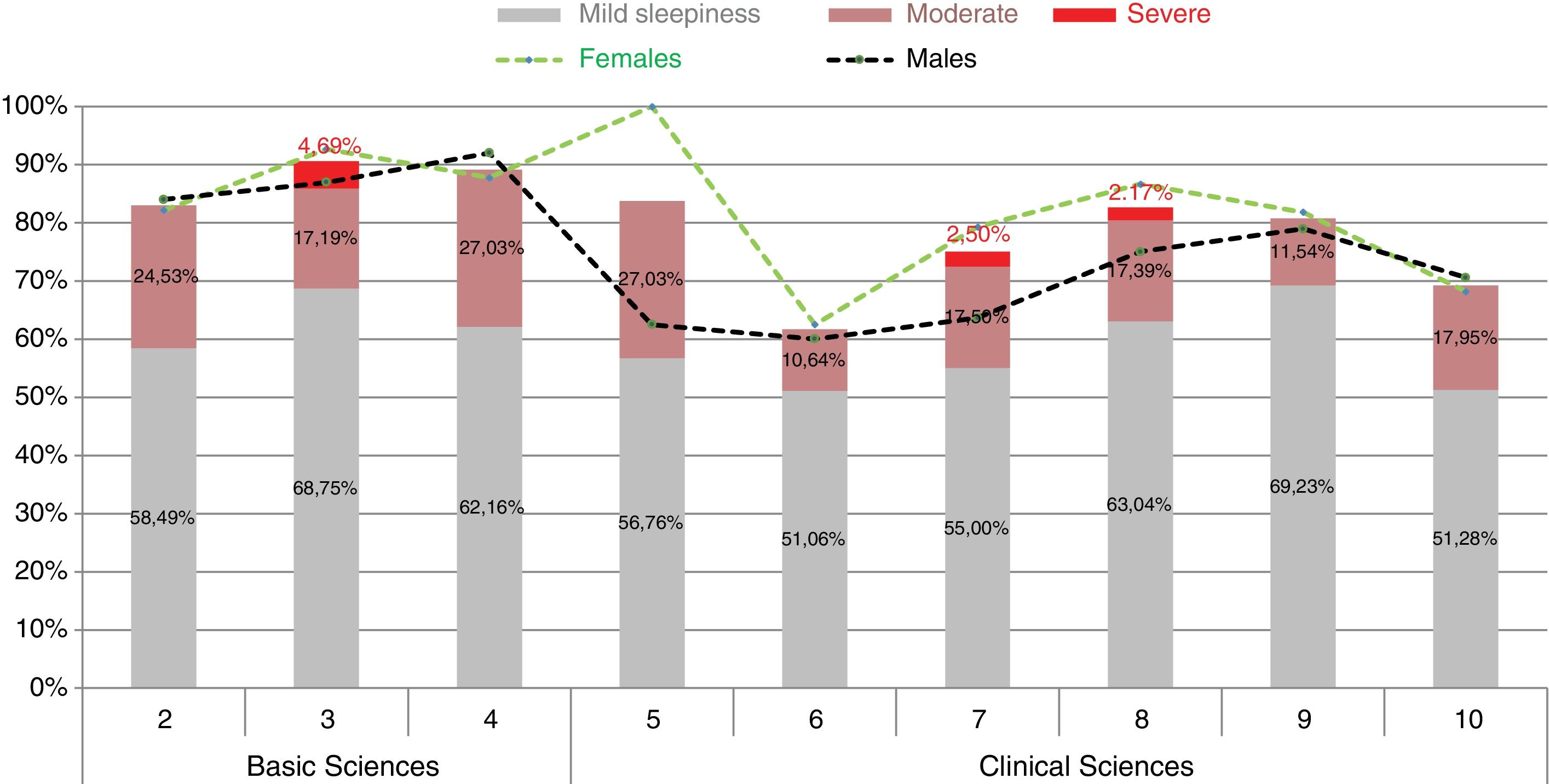

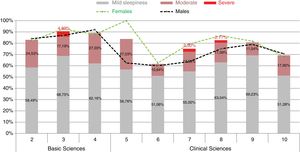

When evaluating the results of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, it was revealed that 80.75% (n=365/453) of respondents obtained scores indicating EDS, with a higher proportion of women – 82.81% (n=236/288) – than males affected – 77.25% (n=129/170). According to the severity of the EDS (mild, moderate and severe), the students who were studying the third semester presented a higher prevalence of severe EDS (4.69%) and those in the ninth semester had a higher prevalence of mild daytime sleepiness (69.23%) (Fig. 3). Furthermore, 80.55% of those affected with EDS reported poor quality of sleep and 42.19% reported poor sleep hygiene.

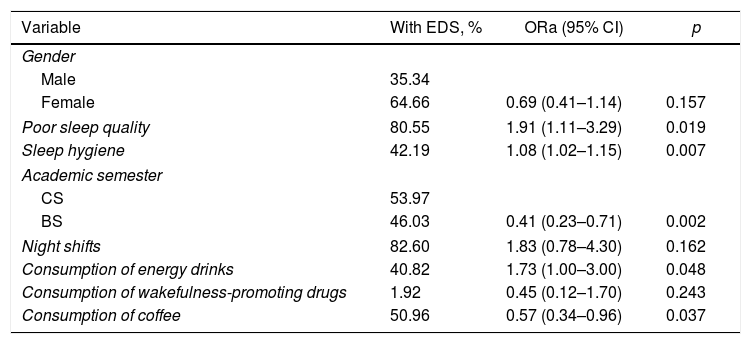

Bivariate analysis of EDS and associated variablesA significant association was found between EDS and poor sleep quality (OR=1.92; 95% CI, 1.11–3.29; p=0.019); with regard to sleep hygiene, a median of 15 was calculated in students who had EDS, and it was observed that, with each one-point increase above the median, the risk of EDS increased with statistically significant association (OR=1.09; 95% CI, 1.02–1.16; p=0.003). However, when the presence of EDS was compared based on the education cycle, it was revealed that studying the clinical sciences semesters was associated with a lower risk of EDS than the risk of those studying the basic sciences semesters (OR=0.58; 95% CI, 0.24–0.72; p=0.0009).

Furthermore, the consumption of energy drinks was identified as the variable with the highest risk of EDS regardless of the education cycle, with a statistically significant association (OR=1.74; 95% CI, 1.02–1.16; p=0.007). A statistically significant relationship of EDS with gender (OR=0.69; 95% CI, 0.42–1.15; p=0.157), the consumption of wakefulness-promoting drugs without a medical prescription (OR=0.46; 95% CI, 0.12–1.70; p=0.243) or the consumption of coffee (OR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.44–1.20; p=0.20) was not found.

Multivariate analysisIn the multivariate analysis using logistic regression, a similar pattern of significant association between EDS and poor sleep quality and poor sleep hygiene was observed; however, when evaluating the association with doing 12-h night shifts, no statistically significant relationship with EDS was found (OR=1.83; p=0.162). In terms of the consumption of energy drinks, the variable resulted in the risk of EDS being increased, but with a non-conclusive confidence interval. Table 2 presents the multivariate analysis of EDS and associated variables.

Multivariate analysis of EDS and associated variables.

| Variable | With EDS, % | ORa (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 35.34 | ||

| Female | 64.66 | 0.69 (0.41–1.14) | 0.157 |

| Poor sleep quality | 80.55 | 1.91 (1.11–3.29) | 0.019 |

| Sleep hygiene | 42.19 | 1.08 (1.02–1.15) | 0.007 |

| Academic semester | |||

| CS | 53.97 | ||

| BS | 46.03 | 0.41 (0.23–0.71) | 0.002 |

| Night shifts | 82.60 | 1.83 (0.78–4.30) | 0.162 |

| Consumption of energy drinks | 40.82 | 1.73 (1.00–3.00) | 0.048 |

| Consumption of wakefulness-promoting drugs | 1.92 | 0.45 (0.12–1.70) | 0.243 |

| Consumption of coffee | 50.96 | 0.57 (0.34–0.96) | 0.037 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; BS: basic sciences; CS: clinical sciences; EDS: excessive daytime sleepiness.

ORa: adjusted odds ratio.

EDS is a problem which affects most medical students at the UNAB. It is estimated that 80.75% of the students suffer from the condition, a value that exceeds that reported in a study carried out at the Technological University of Pereira (UTP), which revealed a general EDS prevalence of 49.80%.13 However, if the severe forms of EDS in third-semester students are analysed, it can be seen that, although a high percentage (90.63%) suffer from EDS, only 4.69% score the severe forms of the condition, results similar to those reported by a study carried out in third-semester students at the National University of Colombia (UNAL), which found a general prevalence of EDS of 59.60%, but only 6.07%19 of the sample evaluated had the severe form.

It is striking that the basic-cycle students evaluated have a higher risk of EDS, considering that they have a lower amount of credits and fewer hours of classroom-based and independent work and they do not do night shifts, compared to those studying subjects with healthcare-based teaching practices. Although the studies are contradictory, as is observed in one study on medical students in a Peruvian university, in which no difference was found in EDS between those studying the clinical cycle and those studying the basic cycle.20 Another study carried out in a medical school in Medellín (Colombia) found a statistically significant relationship between EDS and the education cycle (OR=1.60; 95% CI, 1.00–2.60; p=0.05),36 although its confidence interval is not conclusive; all of the above could be justified by differences between the different academic programmes.

One hypothesis of the results obtained in our population is that the stress generated by the social and academic demands that the transition to university life implies exposes students to an unknown environment in which they must socialise and create new friend groups, and adapt to a change in the teaching model and a new grading system. The latter considerations lead to the question being raised as to whether the method of study that students follow at school is not very effective in the first semesters, and perhaps for this reason they require a greater number of hours of independent study, mainly in the evening, which has a negative impact on sleep quality and the presence of EDS.

Sleep quality has been related positively to the perception of well-being and self-reported health. A higher quantity of somatic complaints, affective symptoms and little satisfaction with life has been reported.37 In our study, most medical students reported poor sleep quality, which increased the risk of EDS. It was observed that 80.55% of students who reported poor sleep quality presented with EDS, somewhat similar to the results of studies by the UNAL and the UTP, in which poor sleep quality with EDS was found in 79.52%9 and 79.30%13 of the students evaluated.

In addition to poor sleep quality, the fact that 154 students (42.19%) of the 365 with EDS had poor sleep hygiene is also noteworthy. In other words, when students do not have good sleep habits and different disruptive behaviours are presented, there is an increased risk of EDS. These data concur with those found in medical students at the UNAL, where 44.58% reported poor sleep hygiene.9 One of the main factors which alters the sleep pattern of medical students is the exposure to night shifts as part of their training, in which they are forced to remain awake during their normal sleeping period. Although this is associated with circadian rhythm sleep disorders, in our study no significant relationship was found between EDS and carrying out night shifts (p=0.162), which is consistent with the findings of the UNAL study, in which doing night shifts was not associated with EDS (p=1.171).9 These findings could be explained by the divergence between the intensity of the schedule and the number of hours working night shifts in the different semesters and programmes but, due to the fact that our study has a cross-sectional design, this causal link cannot be established.

Another bad habit that has been linked to sleep disorders is the drinking of coffee hours before going to sleep with the aim of voluntarily depriving oneself of sleep, as it has an impact on sleep quality and quantity23; the primary ingredient of energy drinks is caffeine, along with other substances such as guarana, taurine, glucuronolactone and sugar derivatives, among others.21 These drinks are ingested with the aim of perceiving a subjective feeling of well-being and increased energy, as well as to increase the number of waking hours, given that they act as central nervous system stimulants.

This consumption habit is common among medical students, as revealed in four schools in Karachi (Pakistan), where it was determined that 52% use energy drinks, with two main objectives: to reduce the hours of sleep and to study or complete academic tasks.38 In South America, this phenomenon has also been studied: at the Universidad de Chile [University of Chile], 43.00% of students said they had consumed energy drinks,39 and at the Universidad de Buenos Aires [University of Buenos Aires], this figure was 58.80%.40 In our study, it was observed that 70.77% of students surveyed consume energy drinks, and the multivariate analysis found that this behaviour generates a higher risk of EDS, probably because, when prolonging the hours of study at night, the amount of sleep is insufficient, but with non-conclusive bidirectional behaviour, which is perhaps justified by the time difference of consumption. However, this was not evaluated in this study, meaning that the impact of the timing on sleep was not identified.

Finally, self-medication is a common phenomenon in the university environment, as is revealed in the study carried out by the Universidad de Antioquia [University of Antioquia] in 2002, in which it was found that 97.00% of the university students surveyed had taken a medicine without a medical prescription at some point in their life. Among the reasons for this behaviour, there is evidence of factors related to the health system (travelling to the healthcare institution, waiting to be seen and copayment charges), to the medication (feeling of familiarity) and to individuals (low risk perception, influence of a friend or family member).41 In this study, it was found that 6.52% of medical students said they had consumed drugs which modify the sleep pattern. Of the 17 students who reported this behaviour, 15 were studying clinical cycle subjects, meaning they had already passed the subjects related to the pharmacological basis of therapy, which could give them a sense of safety with the use of psychotropic drugs.

It is common to find this behaviour in medical students: at Midwestern University in the United States, 15.20% of students reported using wakefulness-promoting substances without a medical prescription42 and at the Universidad de Buenos Aires [University of Buenos Aires], 45.09% admitted taking these medicines.40 In France, in a study on 1718 medical students and graduate doctors, 33.00% had used them at some point in their lives.43 A systematic review on the use of methylphenidate by medical students found that 34.80% had used the drug before going to university, but most (65.20%) reported that the first time was at university. Among the reasons stated by students, 62.50% said that it improved concentration, 59.80% that it helped them study and 47.50% that it increased waking hours.43 Therefore, it is clear that the use of psychotropic drugs is common in this study population and is related to the start of university life.44

Although the results of this study provide statistical evidence to formulate plausible hypotheses on the association between EDS and poor sleep quality in medical students, the fact that it is a cross-sectional study means there is not sufficient scope to evaluate causality hypotheses, as it does not comply with the temporality criterion. However, the information and the associations found make it relevant and justify the conduct of prospective studies to assess the risk factors of sleep disorders in this type of population.

ConclusionsIt is common for medical students to suffer from EDS but only a small percentage have a severe form of this sleep disorder. It is therefore important to conduct preventive educational programmes and to implement screening tests to promptly identify this health problem, which can have a negative impact on the academic performance of medical students.

Furthermore, as has been shown, this health problem is more common in students who are in the basic cycle, despite having fewer credits and not doing night shifts as in the clinical cycle, which highlights the importance of evaluating the method of study and accompanying students in the transition from school to university life.

Although more than half of the medical students reported good sleep hygiene, the fact that most consume energy drinks is contradictory, which leads us to believe that they are not clear about sleep hygiene measures or they underestimate the negative consequences that the consumption of these drinks can have on sleep quality.

While the use of wakefulness-promoting drugs in students is rare, it is important to provide information on the adequate use of the medicines, thereby improving the risk perception that self-medication involves.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Niño García JA, Barragán Vergel MF, Ortiz Labrador JA, Ochoa Vera ME, González Olaya HL. Factores asociados con somnolencia diurna excesiva en estudiantes de Medicina de una institución de educación superior de Bucaramanga. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2019;48:222–231.