In order to determine whether a medical professional is criminally liable for reckless conduct, a judge has to use a range of criteria. In modern legal doctrine, and especially in Colombian jurisprudence, it is increasingly important to assess to what extent a medical professional's conduct falls within the permitted margin of risk.

ObjectiveTo examine the importance for legal professionals of evaluating risk in the context of determining criminal liability pertaining to reckless conduct.

MethodologyThe methodology used was the dogmatic criminal law approach; concepts embodied in the meaning of crime and that are needed to establish criminal liability of an individual were interpreted and systematized. The background material was the result of a search of national and international papers on this subject matter, and the decisions issued by the Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice, Colombia, between 1995 and 2016 were reviewed.

ResultsThere is a consensus between the majority doctrine and the criminal jurisprudence about the importance of assessing the presence of risk in medical practice.

ConclusionsIn cases where the medical action results in harmful consequences for the patient but there is proof that the physician performed within to the allowable parameters of risk for the particular procedure, the medical professional shall be considered exempt from any criminal liability.

Para determinar la existencia de la responsabilidad penal como consecuencia de un comportamiento imprudente provocado por un profesional de la salud, es preciso que el juez, parta de evaluar diferentes criterios que le permitan identificar si estamos en presencia de una conducta penal. En la doctrina moderna y en la jurisprudencia de nuestro país, se viene exigiendo precisar sí la actuación del médico se hizo dentro del marco del riesgo permitido.

ObjetivoExaminar la trascendencia que para el operador jurídico tiene la valoración del riesgo a la hora de verificar la responsabilidad penal del médico por conductas imprudentes.

MetodologíaLa metodología aplicada fue la dogmática jurídico penal, es decir, se interpretaron y sistematizaron conceptos que hacen parte del significado del delito y que son necesarios para la determinación de la responsabilidad penal de una persona. En cuanto al material utilizado, se hizo un rastreo de obras nacionales e internacionales en torno a esta temática y se revisaron las decisiones emitidas por la Corte Suprema de Justicia-Sala Penal, Colombia, desde el año 1995 hasta el 2016.

ResultadosExiste consenso en la doctrina mayoritaria y en la jurisprudencia penal sobre la importancia de valorar la presencia del riesgo en la actividad médica.

ConclusionesEn aquellos casos en los que la actuación médica genera un resultado lesivo para el paciente, pero se comprueba que el galeno actuó bajo los parámetros del riesgo permitido propio de su actividad, se deberá eximir de responsabilidad penal al profesional de la salud.

Usually, reckless behavior in medical practice is associated with verification of breach of the objective duty of care; however, although this a determinant criterion, it is not the only one to be evaluated by the judge, since the unjust imprudent type comprises both a subjective and objective perspective.1

The subjective view of recklessness shall be analyzed from two different angles, one negative and one positive. The former involves the absence of deceit – awareness and will to perform the objective type, for instance the awareness and will to kill, injure, or endanger the life of the patient; the latter involves the potential to exercise caution – the possibility for the physician to foresee that his/her reckless action may cause the patient harm – and prevention; i.e., the physician's ability to prevent a poor outcome for the patient, in accordance with timeliness, modality, and place. As mentioned in a previous paper, the judge is required to make the assessment based on the criterion of the ideal average individual, in the same context as the individual who presumably acted recklessly.2 For instance, if an orthopedic surgeon acted with negligence, the judge must make an analysis based on the care and diligence of a careful orthopedic surgeon under the same conditions as the physician who acted recklessly; however, what the judge should refrain from doing is benchmarking against any surgeon or physician from a different specialty.3

With regards to the objective view, it entails what we have called the core of reckless crime – although other elements exist, this one is the most relevant.4 This assumes that the judge must make sure that the physician failed to use care and diligence according to the medical standards, failing to comply with his/her professional duties.2 To reach this conclusion, keep in mind that care involves both the obligation to take action and to refrain from taking action,5 for instance when lex artis rule requires that a patient with pneumonia shall be treated with antibiotics; however, if the patient is allergic to antibiotics, the physician must refrain from prescribing these drugs. Therefore, emphasis must be placed on the duty of care, both in doing as in refraining from doing.

Notwithstanding the above, making sure that the physician's behavior was against the standards, regulations, guidelines, and protocols of medical practice, is not sufficient to determine the criminal liability of the physician, since there is a close relationship between the duty of care and the risk taken by the healthcare professional. Consequently, henceforth, we shall refer to the medical doctor on the basis of doctrine and jurisprudence, specifying that occasionally some doctors dispense with studying violations to the objective duty of care and consider it merely as a verification of medical actions that place the patient's health and life at risk.2

The importance of risk in the medical activity as a determining criterion for criminal liabilityThe doctrine perspectiveAccording to contemporary doctrine and jurisprudence, risk assessment to determine the occurrence of reckless behavior is essential because it recognizes dangerous medical practice and acknowledges that the practice of medicine involves certain risks that even when damages occur, these may not be considered criminally relevant.6 In other words, there may be situations in which the behavior of a healthcare professional, despite injuring the patient, the outcome may be considered a random occurrence or an inherent risk to the practice of the medical profession.

In the recent doctrine, the study of care offenses1 additionally requires that the individual with his/her behavior exceeds the allowable limits; therefore, what is essential is to determine whether the physician generates a risk that exceeds the limits accepted according to the standards of the medical profession.7

According to some authors8 “the normative duty of care or diligence is only reasonable with regards to those behaviors or situations endangering beyond the legally acceptable risk. Therefore, lack of care is a necessary but insufficient condition, since not all care violations result in reckless crime; an additional specific normative element is required, and that is the risk created. This involves determining what risks or dangers should have been prevented by healthcare professionals9; therefore, there is no infringement by the caregiver if the allowable risk is not exceeded”.2

According to Corcoy Bidasolo, the objective duty of care and the allowable risk are autonomous elements each with its own content.10 Therefore, in the opinion of the author, both should be considered when ruling the occurrence of reckless behavior. The judge must study each independently, since in terms of reckless behavior involving medical liability, it must be acknowledged that in addition to lex artis rules, the risk taken by the healthcare professional with his/her actions, play a very important role; medical practice in itself is highly dangerous and entails a risk that the healthcare professional is entitled to take.

In contrast however, other doctrines11 assign a more predominant role to recklessness to such an extent that they claim that the duty of care and recklessness itself wear out under objective imputation; the duty of care is subsumed into the allowable risk. Proving that that the physician's action involved a legally unacceptable risk should be enough. Apparently this is the dominant position in Colombian jurisprudence with regards to medical criminal liability, as we shall discuss in subsequent paragraphs.

Roxin11 further explains that infringement of duty of care may be disregarded under reckless crime; in is own words, this element is “wrongful from the logical perspective of the standard” since focusing on the infringement of the objective duty of care may lead to the conclusion that reckless crimes may only be perpetrated unintentionally; they are the result of omission. Hence, according to the author, the healthcare professional may only be liable for instance when failing to perform a surgical procedure that is life-saving for the patient. This disregards the possibility of making the physician liable if during the procedure an action results in an infection that causes the patient's demise. Consequently, the author believes that the physician is to be charged, not because of carelessness, but because of dangerous behaviors that are not endorsed by professional standards that make him/her accountable both for action and for omission.

Along the same lines, Jakobs12 also rejects the assessment of duty of care and even claims that in reckless crime there is no infringement of the duty of care and therefore what the physician should be punished for is a behavior that generates a risk beyond the professional standards.

Notwithstanding the above, this particular paper considers that the allowable risk is not a substitute for the duty of care, nor does the latter replace the former; on the contrary, both criteria are complementary. Therefore, if the physician with his/her behavior meets the care standards required under lex artis and additionally controls hazards, there will be no grounds for criminal liability. Hence, we may conclude that prudent measures are governed by medical care standards and hazard control is determined by the risk limits of the activity per se2; with regards to the former, there is a need to determine whether the physician failed to comply with the objective duty of care and with regards to the latter, whether the healthcare professional gave rise to a criminally relevant risk that exceeds the protective measures of the standard of professional care. Consequently, if the physician proceeds in accordance with the allowable risk, his/her actions shall be construed as pursuant to a justifiable cause.1

At is point, a question arises: when do we face allowable risks in medical practice? In accordance with Paredes Castañón5 the answer to this question must weigh the cost/benefit ratio. For instance, in case of surgery, the potential damages to the patient's recovery shall be assessed under the medical standards, as well as the advantages of performing the procedure. Is a comparison between the advantages and disadvantages, analyzing which option is best for the patient. Hence the judge shall be able to decide whether the physician's actions increased or decreased the level of risk involved in the surgical procedure for the patient. This author clearly states: “The cost/benefit analysis under the legal system is the necessary foundation for passing a verdict on the case and determining the maximum allowable risk”.

However, in the opinion of other authors it is impossible to establish such criteria because they follow mechanistic rules13 with difficult to apply statistical probabilities since there is no cost or benefit in medicine; just a final goal that translates into protecting the life of the patient. In medical practice, all consubstantial factors and circumstances surrounding the procedure in a particular case must come together.

We feel that in medical practice there is a need to weigh the benefit versus the impact of any health intervention. The physician shall strive to protect the life of the patient and recover his/her health status; however, both life and health could be affected by the physician's intervention. Therefore, it is impossible and inappropriate to design a hypothetical formula to determine exactly when the physician's actions have gone beyond the allowable risk. The judge is required to evaluate each case individually, based on the premise of the ideal practitioner to determine whether an exaggerated risk was created for the patient by using a method or treatment that impaired the patient and infringed the duty of care rule in medical practice.

To close this discussion, it has to be said that in terms of the risks involved in the practice of medicine, the criminal doctrine usually distinguishes between typical and atypical risks.2,14 The former is those that are objectively foreseeable15 and therefore “frequently occur in certain pathologies, for instance fatty embolisms in patients undergoing long bone surgery; embolism as a result of significant blood vessel destruction”2; nosocomial infections when the patient has been hospitalized for a long time in the ICU; the risk of thrombosis in patients with metastatic disease,16 inter alia. Atypical risks are those with a lower frequency as compared to the typical risks. These may rarely occur and are unforeseeable and hence atypical, such as bronchospasm following spinal anesthesia.17

Thus it can be concluded that the physician is only required to foresee typical risks involved in the practice of his/her profession and failure to do so may lead to criminal liability because his/her failure to comply with duty of care and lack of preparedness resulting in an unusual or heightened risk. Nevertheless, when atypical, difficult to predict risks arise, the outcome may not be attributed to the physician's actions but rather to a fortuitous occurrence.

Dealing with risk under the Colombian criminal jurisprudenceThere is little data in Colombia about the number of judicial decisions issued in the criminal jurisdiction with regards to medical liability at different instances, and much less regarding the criteria adopted by judges to charge or acquit the healthcare professional from responsibility. The information available about legal proceedings against medical staff is very general. Most of the studies provide quantitative rather than qualitative results, with regards to the arguments of judges when passing judgment.

So, with regards to the number of proceedings, research indicates that between the year 2000 and 2003, the proceedings involving medical liability in Colombia increased by 75%, with a prevalence of criminal accusations and ethical and civil claims,18 of which 43% were criminal charges. Similarly, between 2005 and 2010, the Forensic Clinic research, Bogota office, completed a statistical analysis and issued reports based on the data collected from the Colombian Institute of Forensic Medicine in Bogota, concluding that 51.99% of the cases reported were from private healthcare providers and 43.28% from public institutions; the remaining 4.72% failed to provide any information. Most claims were against healthcare practitioners and against the government, with 59% of criminal charges.19

There is a study with similar criteria to those used by the judicature to establish criminal liability of physicians due to recklessness published in 2013. The study used a jurisprudence analysis in an attempt to answer the question of whether the rulings of the Supreme Court of Justice (hereinafter SCJ), lead to the conclusion that medical practice is a dangerous or risky activity. The text examines some decisions adopted by the Supreme Court of Justice regarding establishing liability when undertaking dangerous activities, but in particular, focuses on the decision of April 11, 2012 of the Criminal Court of Appeals, Judge Writing of the Court: Augusto Ibáñez, File 33920, provision considering medical practice as a risky activity.20

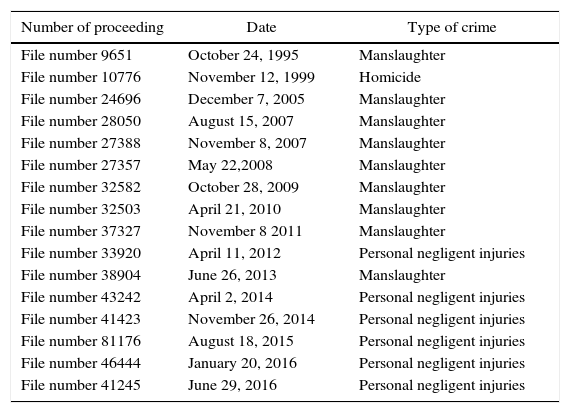

This highlights the fact that during the last few years, the medical criminal liability issues are becoming increasingly relevant in criminal courts of justice. However, the academic publications fail to mention the argumentative criteria used to convict, acquit, or declare the appeal inadmissible. Consequently, we have tracked the decisions of the Supreme Court of Justice – Criminal Chamber – between 1995 and 2016, identifying 16 verdicts, of which 10 were manslaughter and the remaining six were crimes for personal negligent injuries. Table 1 lists the decisions.

Court orders of the criminal chamber of Supreme Court of Justice on decisions related with medical criminal liability.

| Number of proceeding | Date | Type of crime |

|---|---|---|

| File number 9651 | October 24, 1995 | Manslaughter |

| File number 10776 | November 12, 1999 | Homicide |

| File number 24696 | December 7, 2005 | Manslaughter |

| File number 28050 | August 15, 2007 | Manslaughter |

| File number 27388 | November 8, 2007 | Manslaughter |

| File number 27357 | May 22,2008 | Manslaughter |

| File number 32582 | October 28, 2009 | Manslaughter |

| File number 32503 | April 21, 2010 | Manslaughter |

| File number 37327 | November 8 2011 | Manslaughter |

| File number 33920 | April 11, 2012 | Personal negligent injuries |

| File number 38904 | June 26, 2013 | Manslaughter |

| File number 43242 | April 2, 2014 | Personal negligent injuries |

| File number 41423 | November 26, 2014 | Personal negligent injuries |

| File number 81176 | August 18, 2015 | Personal negligent injuries |

| File number 46444 | January 20, 2016 | Personal negligent injuries |

| File number 41245 | June 29, 2016 | Personal negligent injuries |

Source: Supreme Court of Justice Rapporteur's Report. Criminal Chamber. Court Decisions issued between 1995 and 2016, Colombia.

What is really interesting is that in most of the decisions, the SCJ focuses its evaluation criteria on the theory of objective imputation and risk analysis; we may then conclude that since 1995 the SCJ welcomes Roxin's theory21 – notwithstanding the fact that this theory became stronger under the jurisprudence doctrine on medical liability, since the enactment of Law 599 of 2000, also known as the criminal code –.22 But, in contrast to what Roxin argues, not in every decision the risk analysis supersedes the review of the infringement of the objective duty of care and in some cases complements it23 or claims problems pertaining to the presence of a causal relationship between the alleged infringement and the injury inflicted to the patient.24 In other cases there is a clear interest in assessing the risk as an autonomous and independent component.25,26

As of 2008 we can attest that the SCJ unifies criteria regarding risk analysis in medical practice. The SCJ clearly states under Verdict No. 2735727: “In case of a potential guilty conduct, the judge shall initially assess whether the individual gave rise to a legally unacceptable risk form an ex ante perspective; i.e., rewinding to the time when the action took place and examining whether in accordance with the position of an intelligent observer taking the place of the practitioner – with his/her specialized knowledge – the action was appropriate/inappropriate to generate the typical result”.27

Hence, the SCJ has stated that when the physician behaves in such way as to give rise to a legally unacceptable risk, an objective imputation may follow. Such risk arises when the physicians’ behavior violates lex artis and intensifies (increases of heightens) the danger of inflicting damage.28

It must also be said that the SCJ emphasizes the importance of signing the informed consent but requires it to include information about any risks involved with the medical treatment administered to the patient. Failure to produce the informed consent, or improper recording thereof, is considered first a failure to comply with duty of care, and second an increased risk.28 Therefore, not having an informed consent is a criterion that in the opinion of the Court shall influence the decision about the criminal liability of the healthcare professional.29

This means that the SCJ relies on criteria that legally determine when, despite the occurrence of a risky action, such action may not be legally unacceptable and hence become grounds for exclusion of unlawfulness, for instance: a behavior within the scope of danger established under the regulations of the particular community29; or, “when within the framework of cooperation with division of labor in medical practice, the individual performs the duties required but someone else in the team fails to comply with the corresponding rules (lex artis)”28; i.e., performs according to the principle of trust whereby “a normal individual expects the other to perform in accordance with the legal mandate under his/her competency”30; also when the behavior is the result of a mischievous self-inflicted hazard by the patient, for instance in the case of non-compliant patients.

ConclusionThere are different doctrine and jurisprudence positions with regards to the elements involved in medical recklessness. The first, which is consistent with the criterion herein discussed, indicates that both infringing the objective duty of care, as well as the generation, promotion or elevation of risk, are complementary factors and in every case shall be assessed by the judge. If one of these two factors is missing, there will be no grounds for a verdict of criminal liability of the healthcare professional. The second one relates to the position adopted by the Colombian jurisprudence that considers that the assertion of the presence of risk is enough, since the breach of duty of care precludes the verification of risk.

At any rate, regardless of the doctrine or jurisprudence position adopted, when ruling whether there is criminal liability of the physician or not, it is critically important for the judge to assess the level of risk involved in the behavior of the healthcare practitioner. Therefore, in the absence of heightened risk, the practitioner may be acquitted either because of dismissal of the accusation, or because of a cause for vindication.

FundingThis article is the result of a research project “Epistemological foundations for training in medical liability in Colombia”, code 25-000014 and was financed through Grant 01, 2016 of Universidad Autónoma Latinoamericana (UNAULA), Colombia.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Please cite this article as: Vallejo-Jiménez GA. La valoración jurídica del riesgo como criterio para la determinación de la responsabilidad penal del médico. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2017;45:58–63.