This observational retrospective study aimed to investigate the usefulness of Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA), Quick SOFA (qSOFA), National Early Warning Score (NEWS), and quick NEWS in predicting respiratory failure and death among patients with COVID-19 hospitalized outside of intensive care units (ICU). We included 237 adults hospitalized with COVID-19 who were followed-up on for one month or until death. Respiratory failure was defined as a PaO2/FiO2 ratio ≤200mmHg or the need for mechanical ventilation. Respiratory failure occurred in 77 patients (32.5%), 29 patients (12%) were admitted to the ICU, and 49 patients (20.7%) died. Discrimination of respiratory failure was slightly higher in NEWS, followed by SOFA. Regarding mortality, SOFA was more accurate than the other scores. In conclusion, sepsis scores are useful for predicting respiratory failure and mortality in COVID-19 patients. A NEWS score ≥4 was found to be the best cutoff point for predicting respiratory failure.

El presente estudio retrospectivo observacional tiene como objetivo analizar la utilidad de las escalas SOFA (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment), qSOFA (Quick SOFA), NEWS (National Early Warning Score) y Quick NEWS para predecir el fallo respiratorio y la muerte en pacientes con COVID-19 atendidos fuera de la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos (UCI). Se incluyeron 237 adultos con COVID-19 hospitalizados seguidos durante un mes o hasta su fallecimiento. El fallo respiratorio se definió como un cociente PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200mmHg o la necesidad de ventilación mecánica. Setenta y siete pacientes (32,5%) desarrollaron fallo ventilatorio; 29 (12%) precisaron ingreso en UCI, y 49 fallecieron (20,7%). La discriminación del fallo ventilatorio fue algo mayor con la puntuación NEWS, seguida de la SOFA. En cuanto a la mortalidad, la puntuación SOFA fue más exacta que las otras escalas. En conclusión, las escalas de sepsis son útiles para predecir el fallo respiratorio y la muerte en COVID-19. Una puntuación ≥ 4 en la escala NEWS sería el mejor punto de corte para predecir fallo respiratorio.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first reported in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China.1 Following its rapid worldwide spread, coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020.2 The current COVID-19 pandemic is creating unprecedented challenges to healthcare systems across the world, particularly in areas with large community transmission such as the region of Madrid (Spain), where the number of cases increased exponentially during the first three weeks of March 2020.3

The sudden emergence of an infection in which severe pneumonia is the main clinical feature poses a huge challenge for hospital organization in terms of ensuring the availability of adequate respiratory support for patients. In this context, it seems essential to have validated tools that can determine, as quickly as possible, which SARS-CoV-2-infected patients are at a higher risk of developing respiratory failure and/or dying.

The Sepsis-3 task force recommends the quick Sequential (Sepsis-Related) Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score for identifying patients with suspected infection who are at greater risk of poor outcomes.4 Subsequent publications found that general early warning scores, such as the National Early Warning Score (NEWS), were more accurate than the qSOFA score for predicting clinical deterioration.5,6 Some authors propose using a simplified modification of NEWS called quick NEWS (qNEWS).6 These scores’ accuracy in predicting a poor clinical outcome have not previously been reported in patients with COVID-19.

This study aimed to evaluate the use of two sepsis-focused criteria, SOFA and qSOFA, and two general early warning scores, qNEWS, and NEWS, calculated at admission for predicting respiratory failure and death among patients with confirmed COVID-19.

Materials and methodsStudy population and designThis work is a retrospective observational study including all hospitalized adult patients with COVID-19 on March 16, 2020. This day marked the beginning of the worst wave of the epidemic in our region to date.

Patient follow-up continued until April 16, 2020 or death. COVID-19 was diagnosed via a SARS-CoV-2 real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of a nasopharyngeal swab or sputum samples.

Clinical characteristics, radiological features, laboratory values, and vital signs at admission were gathered from electronic medical records. For the validation of each case, all the vital signs and laboratory data necessary to calculate qSOFA, SOFA, NEWS, and qNEWS were determined (see Supplementary Table 1). The first available data from each patient were used to calculate the scores. qNEWS values were calculated using only the blood pressure, respiratory rate, and level of consciousness components of NEWS with the same weightings for each cutoff as in NEWS.6

The protocol was approved by the 12 de Octubre Hospital Review Board (reference 20/117) and a waiver of informed consent was granted due to the study's retrospective observational design.

Definition of endpointsRespiratory failure was defined as a PaO2/FiO2 ratio ≤200mmHg7 or the need for mechanical ventilation (either non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (including high-flow nasal cannula oxygen) or invasive mechanical ventilation). Respiratory failure could occur at any time during hospital admission. As Supplementary Table 2 shows, the median time from admission to respiratory failure was 3 days (interquartile ranges: 1–5.7). In-hospital mortality during the 30-day follow-up was recorded.

Statistical methodsDescriptive analysis was performed using means±standard deviation or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables with a non-normal distribution and Fisher's exact test to compare proportions. Predictive accuracy was estimated using sensitivities, specificities, negative and positive predictive values, and negative and positive likelihood ratios. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to determine the best SOFA, qSOFA, NEWS, and qNEWS cut-off value associated with the presence of respiratory failure or in-hospital death by means of Youden's index. Statistical analysis was performed with using SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

ResultsA total of 237 patients were included. Patients’ main demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Supplementary Table 2. The median time from the onset of symptoms to the first positive RT-PCR was 5 days (interquartile range: 3–7).

During hospitalization, 70% of patients needed oxygen therapy while respiratory failure was observed in 32% of cases. ICU admission and overall in-hospital mortality occurred in 12.2% and 20.7% of patients, respectively. Mortality was higher in the respiratory failure group (47/77 (61%) vs. 2/160 (1.3%), p<.0001). ICU mortality was 41.4% (12/29) vs. 17.8% (37/208) in non-ICU patients (p<.0001).

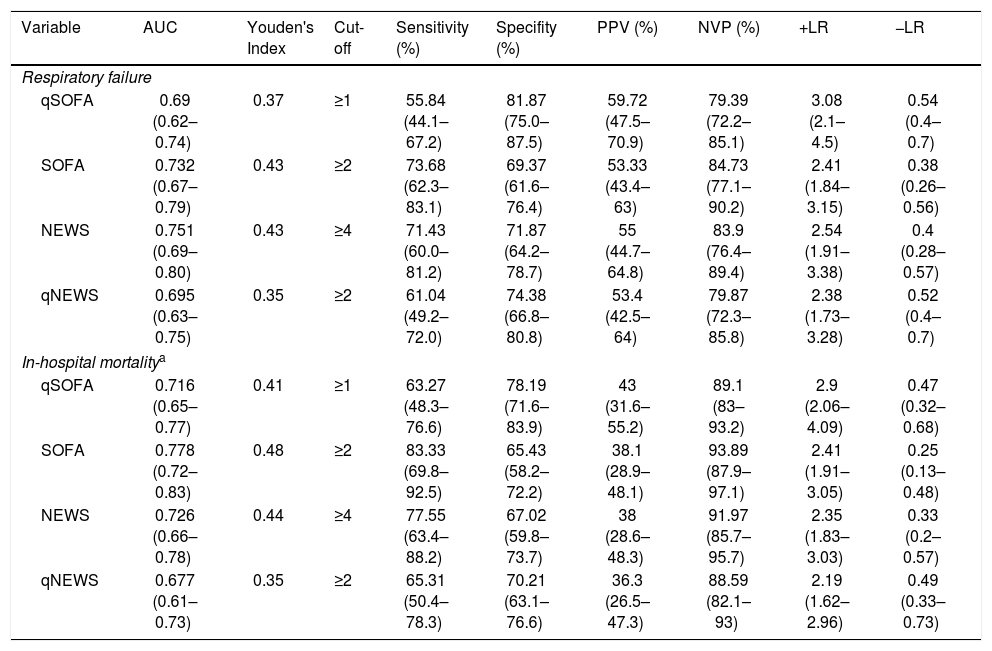

The most common SOFA, qSOFA, NEWS, and qNEWS values at admission were 0 (35%), 0 (69%), 2 (15.6%), and 0 (57.8%). Measures of the diagnostic accuracy of SOFA, qSOFA, NEWS, and qNEWS for the presence of respiratory failure or in-hospital death are shown in Table 1. The best cut-off values for predicting respiratory failure and mortality for qSOFA, SOFA, NEWS, and qNEWS were ≥1, ≥2, ≥4, and ≥2, respectively. These cut-off points were observed in 30.4%, 45.5%, 42.2%, and 22.4% of the study cohort.

Measures of diagnostic accuracy for respiratory failure and in-hospital mortality for each score.

| Variable | AUC | Youden's Index | Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specifity (%) | PPV (%) | NVP (%) | +LR | −LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory failure | |||||||||

| qSOFA | 0.69 (0.62–0.74) | 0.37 | ≥1 | 55.84 (44.1–67.2) | 81.87 (75.0–87.5) | 59.72 (47.5–70.9) | 79.39 (72.2–85.1) | 3.08 (2.1–4.5) | 0.54 (0.4–0.7) |

| SOFA | 0.732 (0.67–0.79) | 0.43 | ≥2 | 73.68 (62.3–83.1) | 69.37 (61.6–76.4) | 53.33 (43.4–63) | 84.73 (77.1–90.2) | 2.41 (1.84–3.15) | 0.38 (0.26–0.56) |

| NEWS | 0.751 (0.69–0.80) | 0.43 | ≥4 | 71.43 (60.0–81.2) | 71.87 (64.2–78.7) | 55 (44.7–64.8) | 83.9 (76.4–89.4) | 2.54 (1.91–3.38) | 0.4 (0.28–0.57) |

| qNEWS | 0.695 (0.63–0.75) | 0.35 | ≥2 | 61.04 (49.2–72.0) | 74.38 (66.8–80.8) | 53.4 (42.5–64) | 79.87 (72.3–85.8) | 2.38 (1.73–3.28) | 0.52 (0.4–0.7) |

| In-hospital mortalitya | |||||||||

| qSOFA | 0.716 (0.65–0.77) | 0.41 | ≥1 | 63.27 (48.3–76.6) | 78.19 (71.6–83.9) | 43 (31.6–55.2) | 89.1 (83–93.2) | 2.9 (2.06–4.09) | 0.47 (0.32–0.68) |

| SOFA | 0.778 (0.72–0.83) | 0.48 | ≥2 | 83.33 (69.8–92.5) | 65.43 (58.2–72.2) | 38.1 (28.9–48.1) | 93.89 (87.9–97.1) | 2.41 (1.91–3.05) | 0.25 (0.13–0.48) |

| NEWS | 0.726 (0.66–0.78) | 0.44 | ≥4 | 77.55 (63.4–88.2) | 67.02 (59.8–73.7) | 38 (28.6–48.3) | 91.97 (85.7–95.7) | 2.35 (1.83–3.03) | 0.33 (0.2–0.57) |

| qNEWS | 0.677 (0.61–0.73) | 0.35 | ≥2 | 65.31 (50.4–78.3) | 70.21 (63.1–76.6) | 36.3 (26.5–47.3) | 88.59 (82.1–93) | 2.19 (1.62–2.96) | 0.49 (0.33–0.73) |

Data are presented as percentages with 95% confidence interval.

All p-values for area under the ROC curve were <.0001 except qNEWS for in-hospital mortality (p=.0001).

PPV: Positive predictive value, NPV: Negative predictive value, +LR: Positive likelihood ratio, −LR: Negative likelihood ratio; qSOFA: Quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; NEWS: National Early Warning Score, qNEWS: quick National Early Warning Score.

NEWS (AUC: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.69–0.8, p<.0001) was the most accurate score for predicting respiratory failure at admission (see Supplementary Fig. 1) and the difference with qSOFA approached statistical significance (qSOFA AUC: 0.69, 95% IC: 0.62–0.74, pairwise comparison, p=.09).

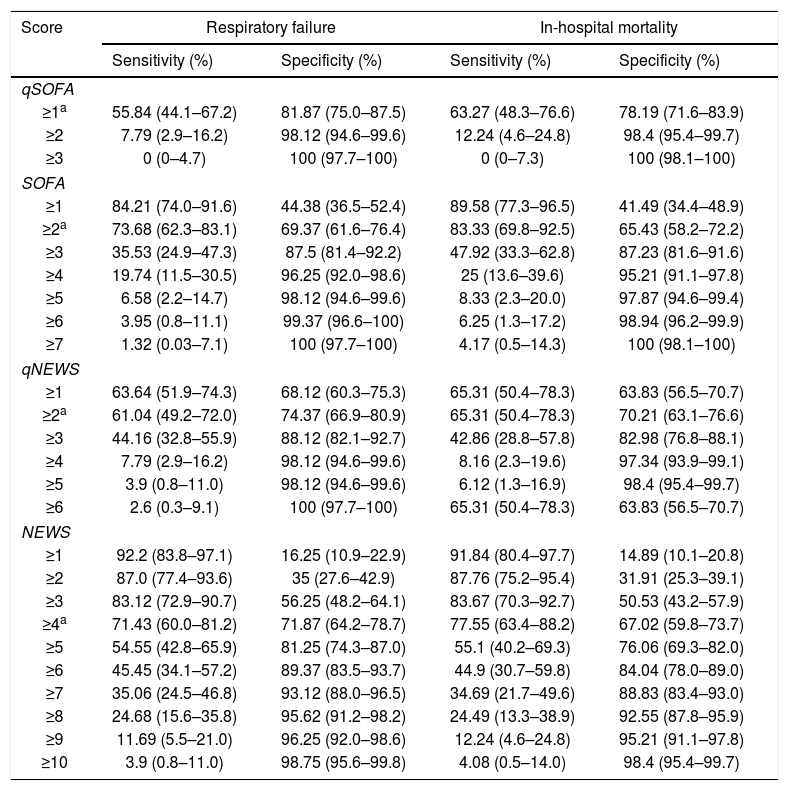

Regarding mortality, SOFA (AUC: 0.77; 95% IC: 0.72–0.83, p<.0001) was slightly more accurate than the other scores (see Supplemenatary Fig. 2 and Table 3). The specificity and sensitivity of different score cut-offs with 95% confidence intervals are listed in Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity for the outcomes across different score cut-offs.

| Score | Respiratory failure | In-hospital mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |

| qSOFA | ||||

| ≥1a | 55.84 (44.1–67.2) | 81.87 (75.0–87.5) | 63.27 (48.3–76.6) | 78.19 (71.6–83.9) |

| ≥2 | 7.79 (2.9–16.2) | 98.12 (94.6–99.6) | 12.24 (4.6–24.8) | 98.4 (95.4–99.7) |

| ≥3 | 0 (0–4.7) | 100 (97.7–100) | 0 (0–7.3) | 100 (98.1–100) |

| SOFA | ||||

| ≥1 | 84.21 (74.0–91.6) | 44.38 (36.5–52.4) | 89.58 (77.3–96.5) | 41.49 (34.4–48.9) |

| ≥2a | 73.68 (62.3–83.1) | 69.37 (61.6–76.4) | 83.33 (69.8–92.5) | 65.43 (58.2–72.2) |

| ≥3 | 35.53 (24.9–47.3) | 87.5 (81.4–92.2) | 47.92 (33.3–62.8) | 87.23 (81.6–91.6) |

| ≥4 | 19.74 (11.5–30.5) | 96.25 (92.0–98.6) | 25 (13.6–39.6) | 95.21 (91.1–97.8) |

| ≥5 | 6.58 (2.2–14.7) | 98.12 (94.6–99.6) | 8.33 (2.3–20.0) | 97.87 (94.6–99.4) |

| ≥6 | 3.95 (0.8–11.1) | 99.37 (96.6–100) | 6.25 (1.3–17.2) | 98.94 (96.2–99.9) |

| ≥7 | 1.32 (0.03–7.1) | 100 (97.7–100) | 4.17 (0.5–14.3) | 100 (98.1–100) |

| qNEWS | ||||

| ≥1 | 63.64 (51.9–74.3) | 68.12 (60.3–75.3) | 65.31 (50.4–78.3) | 63.83 (56.5–70.7) |

| ≥2a | 61.04 (49.2–72.0) | 74.37 (66.9–80.9) | 65.31 (50.4–78.3) | 70.21 (63.1–76.6) |

| ≥3 | 44.16 (32.8–55.9) | 88.12 (82.1–92.7) | 42.86 (28.8–57.8) | 82.98 (76.8–88.1) |

| ≥4 | 7.79 (2.9–16.2) | 98.12 (94.6–99.6) | 8.16 (2.3–19.6) | 97.34 (93.9–99.1) |

| ≥5 | 3.9 (0.8–11.0) | 98.12 (94.6–99.6) | 6.12 (1.3–16.9) | 98.4 (95.4–99.7) |

| ≥6 | 2.6 (0.3–9.1) | 100 (97.7–100) | 65.31 (50.4–78.3) | 63.83 (56.5–70.7) |

| NEWS | ||||

| ≥1 | 92.2 (83.8–97.1) | 16.25 (10.9–22.9) | 91.84 (80.4–97.7) | 14.89 (10.1–20.8) |

| ≥2 | 87.0 (77.4–93.6) | 35 (27.6–42.9) | 87.76 (75.2–95.4) | 31.91 (25.3–39.1) |

| ≥3 | 83.12 (72.9–90.7) | 56.25 (48.2–64.1) | 83.67 (70.3–92.7) | 50.53 (43.2–57.9) |

| ≥4a | 71.43 (60.0–81.2) | 71.87 (64.2–78.7) | 77.55 (63.4–88.2) | 67.02 (59.8–73.7) |

| ≥5 | 54.55 (42.8–65.9) | 81.25 (74.3–87.0) | 55.1 (40.2–69.3) | 76.06 (69.3–82.0) |

| ≥6 | 45.45 (34.1–57.2) | 89.37 (83.5–93.7) | 44.9 (30.7–59.8) | 84.04 (78.0–89.0) |

| ≥7 | 35.06 (24.5–46.8) | 93.12 (88.0–96.5) | 34.69 (21.7–49.6) | 88.83 (83.4–93.0) |

| ≥8 | 24.68 (15.6–35.8) | 95.62 (91.2–98.2) | 24.49 (13.3–38.9) | 92.55 (87.8–95.9) |

| ≥9 | 11.69 (5.5–21.0) | 96.25 (92.0–98.6) | 12.24 (4.6–24.8) | 95.21 (91.1–97.8) |

| ≥10 | 3.9 (0.8–11.0) | 98.75 (95.6–99.8) | 4.08 (0.5–14.0) | 98.4 (95.4–99.7) |

Data are presented as percentages with 95% confidence intervals.

In a situation like the COVID-19 pandemic, it is vital to predict and identify how many patients are at risk of developing respiratory failure and/or death as soon as possible in order to ensure the appropriate availability of hospital facilities and ventilatory support equipment. Therefore, the use of simple tools such as sepsis scores, which are mainly based on clinical signs, would be of great value for improving the clinical management of this population. However, to date, these scores have not been evaluated in COVID-19 patients. Moreover, these scores have been validated to predict death and ICU transfer,5,6 but not respiratory failure.

In our experience, up to 30% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients developed respiratory failure, 12% were admitted to the ICU, and 20% died.

The NEWS score seems to be the most suitable tool for predicting respiratory failure as it has the best AUC, better sensitivity and specificity compared to qSOFA, and similar values when compared to the more complex SOFA score. For both outcomes, SOFA has the highest sensitivity whereas qSOFA has the best specificity. Overall, our results on COVID-19 patients are similar to what other authors have reported in non-COVID-19 patients.8,9

A striking aspect is that in COVID-19, the NEWS cut-off was ≥4, lower than the scores of 5 or 7 which are normally used in sepsis.5,10 This lower cut-off value could be explained by the fact that patients with COVID-19 do not usually present with hypotension—in our study, systolic blood pressure ≤110mmHg was present in just 15% of patients—and only 7% had alteration of level of consciousness.

On the other hand, it should be noted that each score has a high negative predictive value for respiratory failure and mortality, ranging from 79–84% to 88–93%, respectively. Therefore, the inclusion of these scores in the early clinical evaluation of patients with COVID-19 might be useful for accurately excluding the development of serious complications.

Overall, our analysis shows that the use of these scores allows for early identification of patients at higher risk. This has direct clinical implications in a pandemic as devastating as COVID-19, making it easier to plan the allocation of scarce and complex resources like ICU beds and respiratory support equipment. This is especially advantageous because the median time from admission to the emergency department to ICU transfer was 1 day (IQR: 1–5), which implies that patients may require ICU admission in the first hours of their care.

An important strength of our study is that patient follow-up lasted for one month or until death. This increases the reliability of our data, since severe COVID-19 patients may have long hospital stays. In fact, the median hospital stays among survivors with respiratory failure and ICU admission were 21 days (IQR 16–28) and 28 days (IQR 22–33), respectively. Median time to in-hospital death was 9 days (IQR 7–12) (see Supplementary Table 2). These long hospital stays in patients with severe COVID-19 disease must be taken into account in order to wisely manage hospital resources.

Our analysis has the limitations inherent to retrospective studies. However, vital signs and analytical values were obtained in all cases. Furthermore, this work reports the experience of a single center in the particular context of the first wave of the pandemic. Therefore, our data must be validated by others, especially regarding respiratory failure, given that these scores have previously been used for predicting mortality.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, the predictive accuracies of sepsis scores in relation to respiratory failure and in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 were similarly useful to those previously reported in sepsis. Overall, we found that early assessment of NEWS is the best tool for predicting respiratory failure in COVID-19 patients and may allow physicians and hospital managers to ensure appropriate management of non-ICU SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals.

Ethical approvalThe study protocol was approved by the 12 de Octubre University Hospital Review Board (number reference 20/117).

FundingMikel Mancheño-Losa was supported by a “Río Hortega” Research Contract from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CM19/00226).

Author contributionsA. Lalueza, J. Lora-Tamayo, C. de la Calle, and C. Lumbreras designed the study. G. Maestro, J. Sayas, R. García, and A. Lalueza screened the patients. A. Lalueza, J. Lora-Tamayo, C. de la Calle, G. Maestro, J. Sayas, E. Arrieta, M. Mancheño, Á. Marchán, R. Díaz-Simón, A. García-Reyne, and B. de Miguel did data acquisition. A. Lalueza performed the statistical analysis. A. Lalueza and C. Lumbreras created the first draft of the article. A. Lalueza, G. Maestro, M. Catalán, R. García, and C. Lumbreras participated in the data interpretation and edited the article. A. Lalueza and C. Lumbreras wrote the final draft of the article and made all the changes suggested by the coauthors.

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical support of Teresa García of the Clinical Epidemiology Research Department, Instituto de Investigación 12 de Octubre.

Please cite this article as: Lalueza A, Lora-Tamayo J, de la Calle C, Sayas-Catalán J, Arrieta E, Maestro G, et al. Utilidad de las escalas de sepsis para predecir el fallo respiratorio y la muerte en pacientes con COVID-19 fuera de las Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos. Rev Clín Esp. 2022;222:293–298.

The COVID+12 Group is a member of the SEMI-COVID-19 Network, an initiative of the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine (SEMI, as its initials in Spanish).