At the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, health centres were places where there was a high risk of infection, and during the period of lockdown face-to-face health care was substantially reduced, forcing rapid changes in the care of multiple sclerosis patients by the specialised nursing staff in the units and monographic consultations of this disease.

DevelopmentThe experience of the nursing staff of multiple sclerosis units and monographic consultations, in 8 Spanish hospitals, is collected from the beginning of the pandemic and in later stages, and the adaptations that they made to continue caring for patients are specifically described. The scientific literature about how the SARS-CoV-2 has affected patients with multiple sclerosis is also reviewed, as well as the experiences of other multiple sclerosis teams in health centres in other countries.

ConclusionsDuring the lockdown and in later stages, new forms and previously little used forms of care were applied to multiple sclerosis patients. The nursing staff kept contact with them by telephone and online, provided them with information about safety and behaviour in relation to COVID-19. Face-to-face visits, treatments and distribution of medication were adapted. Information was provided about how patients could receive psychosocial support and about how they could maintain their quality of life.

Al comienzo de la pandemia por el virus SARS-CoV-2, los centros sanitarios fueron lugares de alto riesgo de infección y, durante el período de confinamiento, la asistencia sanitaria presencial se redujo notablemente, lo que obligó a realizar cambios rápidos en la atención a los pacientes de esclerosis múltiple por parte de la enfermería especializada en las unidades y consultas monográficas de esta enfermedad.

DesarrolloSe recoge la experiencia del personal de enfermería de las unidades y consultas monográficas de esclerosis múltiple en 8 hospitales de España desde el comienzo de la pandemia y en etapas posteriores. Concretamente, se exponen las adaptaciones que realizaron para continuar atendiendo a los pacientes durante estos períodos. También se revisa la literatura científica acerca de cómo ha afectado el SARS-CoV-2 a los pacientes con esclerosis múltiple, así como las experiencias de equipos de esclerosis múltiple en centros sanitarios de otros países.

ConclusionesDurante el confinamiento y en etapas posteriores se aplicaron formas de atención a los pacientes de esclerosis múltiple nuevas o poco empleadas con anterioridad. El personal de enfermería mantuvo el contacto con ellos por teléfono y vía telemática, proporcionando información sobre medidas de seguridad y protección frente a la infección por SARS-CoV-2, adaptando las visitas presenciales, los tratamientos y la distribución de la medicación, facilitando información para que los pacientes pudieran recibir apoyo psicosocial y sobre cómo mantener su calidad de vida.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about a number of changes in healthcare facilities, both in hospitals and primary care centres. Professionals working in these facilities have had to adapt to these changes quickly. At the beginning of the epidemic, healthcare facilities were high-risk sites for SARS-CoV-2 infection. As a result, measures had to be taken to ensure that chronically ill patients, such as those with multiple sclerosis (MS), could be cared for safely.

MS is an autoimmune neurodegenerative disease that affects 2.8 million people worldwide. It has an estimated prevalence in Europe of 133 per 100,000 inhabitants1 and in Spain of 80–180 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.2 On 24 November 2021, the number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the world was 257,469,528, with 5,158,211 deaths. On the same date, in Spain, the number of confirmed cases was 5,111,842, with 87,904 deaths.3

During the various waves of the epidemic, care for patients with chronic neurological diseases has suffered stress, due to the reorganisation and rationing of resources and services to cover care for individuals with COVID-19. On the other hand, patients with chronic neurological diseases have had to add the threat of COVID-19 to their illness.4

MS is a chronic disease with an unpredictable course, including physical limitations and psychosocial challenges that affect quality of life.5

An international study of 2340 MS patients (including 147 from Spain) with a confirmed (71.9%) or suspected diagnosis of COVID-19 infection (28.1%) found an association between treatment with rituximab and ocrelizumab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies) and increased hospitalisations and admissions to the Intensive Care Unit and with rituximab, greater use of artificial ventilation was also found.6

Following the implementation of confinement, healthcare teams in MS units had to reorganise and redesign their methods of care, taking into account that these patients have special characteristics, such as the treatments they receive, which require special monitoring, and that immunotherapy can pose a risk to MS patients.7 At that time, it was not known whether MS patients were at higher risk of developing a severe form of COVID-19 in the event of SARS-CoV-2 infection, because of the higher frequency of concomitant diseases in these patients, their limited mobility, or because they live in special care facilities or in families. A different approach to these neurological patients than had existed until then became necessary and other forms of care had to be developed.8 Thus, within a short time, the nursing teams of the MS units in different parts of Spain sought resources and new forms of care, so that patients could continue to be cared for while taking into account and overcoming the restrictions of confinement. To lessen the risk of MS patients becoming infected, a variety of remote care modalities and digital technologies were employed and are explained below. Although already practised in some hospitals around the world, “teleneurology” (the use of telecommunication technologies to enable neurological care to be provided when the patient and physician are not present at the same location or time9) had to be adopted for outpatients as an alternative to face-to-face neurology, and will probably continue to be practised in part in a pandemic-free future.10–12

This special article reports the experience of nurses working with MS patients during confinement. It presents what is considered valuable information regarding the care of MS patients and the solutions that were adapted and put into practice under exceptional circumstances. Published works on this topic in the scientific literature have also been reviewed.

ObjectiveThe purpose of this article is to make known the experience of a group of nursing professionals who worked and continue to do so to care for MS patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

DevelopmentThe experience of nine nursing professionals from the Multiple Sclerosis units of eight hospitals in Spain (in Baracaldo, Barcelona, Las Palmas, Madrid, San Sebastián de los Reyes, Seville, and Vigo) during the COVID-19 pandemic is reported, with a retrospective review of published articles related to various aspects of this experience. The information, protocols, and experiences of care work in several Spanish hospitals have been brought together, and the measures that were taken during the period of confinement and afterward are described.

Actions implemented to inform multiple sclerosis patients about COVID-19The nursing staff’s plan of action for MS patients included the following:

- -

Send them information on COVID-19 by e-mail, telephone, or telematically.

- -

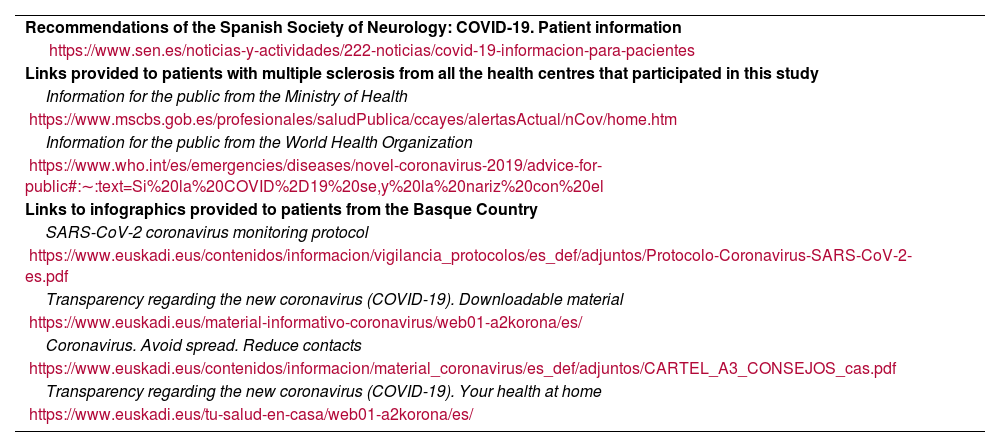

All centres sent information prepared by the MS team and information provided by the Ministry of Health (Table 1) and the autonomous communities.

Table 1.Recommendations and links provided to patients.

Recommendations of the Spanish Society of Neurology: COVID-19. Patient information https://www.sen.es/noticias-y-actividades/222-noticias/covid-19-informacion-para-pacientes Links provided to patients with multiple sclerosis from all the health centres that participated in this study Information for the public from the Ministry of Health https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/home.htm Information for the public from the World Health Organization https://www.who.int/es/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public#:∼:text=Si%20la%20COVID%2D19%20se,y%20la%20nariz%20con%20el Links to infographics provided to patients from the Basque Country SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus monitoring protocol https://www.euskadi.eus/contenidos/informacion/vigilancia_protocolos/es_def/adjuntos/Protocolo-Coronavirus-SARS-CoV-2-es.pdf Transparency regarding the new coronavirus (COVID-19). Downloadable material https://www.euskadi.eus/material-informativo-coronavirus/web01-a2korona/es/ Coronavirus. Avoid spread. Reduce contacts https://www.euskadi.eus/contenidos/informacion/material_coronavirus/es_def/adjuntos/CARTEL_A3_CONSEJOS_cas.pdf Transparency regarding the new coronavirus (COVID-19). Your health at home https://www.euskadi.eus/tu-salud-en-casa/web01-a2korona/es/ - -

In some centres, questions from patients were answered as they came up.

- -

All centres provided patients with the recommendations of the Spanish Society of Neurology (SEN) on hygiene to avoid infection and with respecto to continuing treatment (Table 1).

- -

Information posters on COVID-19 and safety measures were displayed in all health centres.

- -

Infographics were used in mass media (Twitter, Instagram). For example, in the Basque Country, a health advice service was offered to respond to questions and detect cases of COVID-19 (Table 1).

- -

Visits were changed from face-to-face to telephone visits. In general, telephone consultation hours for patients were extended.

In a study using a survey of 176 MS patients, most (80%) were knowledgeable and had a good attitude towards COVID-19, although 46% exhibited anxiety in relation to their treatment and 32% missed their hospital appointment. Moreover, 15% of patients who relapsed did not go to hospital because of the pandemic; 35% missed drug infusions, and 15% discontinued immunomodulatory therapy. The authors of this study believe that telemedicine should be further enhanced to mitigate the effect of the pandemic on the health of MS patients.13

During the pandemic, “telemedicine” has been used for people with MS, as a measure to obviate the need for face-to-face visits.14 In a Norwegian study surveying 135 neurologists concerning outpatients with neurological disorders seen during the first phase of the pandemic, 87% reported increased use of telemedicine, with more significant use of telephone consultations than video consultations, both for initial visits (54% vs. 30%, p < 0.001) and patient follow-up (99% vs. 50%, p < 0.001). Respondents indicated that it was more professionally satisfying to conduct follow-up telephone consultations than for new cases (85% vs. 13%, p < 0.001) and also that teleconsultations were found to be more suitable for headache and epilepsy than for MS and movement disorders. The study also notes that telemedicine was rapidly rolled out in neurology departments within the first few weeks of the pandemic.15 A European study (EU IMI2 RADAR-CNS) indicates that remote monitoring technologies can assist health authorities and help to contain the pandemic.16 On the other hand, social media can serve as platforms to rapidly share information throughout the scientific community. For instance, the social network Twitter was used for this purpose and the hashtag #MSCOVID19 (created in March 2020) was used to report MS cases from Europe and the United States.17

Telephone triage of possible SARS-COV-2 infection or transmissionDuring the period of confinement, some visits to the health centre were necessary. When the patient called with a problem or symptoms, a series of questions were asked to ascertain if they might or might not have COVID-19 infection, or if they had been in contact with an infected person. In March 2020, a digital triage proposal was published that included sending a 10-question questionnaire (with 2–4 answer options) to MS patients to identify those at high risk of COVID-19 infection and to limit unnecessary visits to MS centres. These questions included: 1) age; 2) possible contact with infected persons; 3) whether they had disease-modifying treatment; 4) prior MS treatments; 5) concomitant conditions; 6) blood count in the last month, and, if so, 7) lymphocyte concentration; 8) symptoms compatible with COVID-19, and, if so, 9) whether they had worsened, and, if so, 10) whether they had worsened rapidly.18 At this stage, it has not been reported whether this questionnaire was used and, if so, what results were obtained.

Indications on what to do in case of SARS-CoV-2 infectionBased on the answers provided by the respondents, if COVID-19 infection was suspected, the procedure indicated below was followed:

- -

Suggest that the patient contact their primary care centre. The autonomous communities had a specific COVID-19 telephone number.

- -

The patient should notify the MS unit if he/she had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test.

- -

Patients were informed that it was extremely important to inform the MS unit that they had COVID-19, as modifications to their treatment programme may be required.

- -

Patients were asked to keep the MS team appraised of their situation.

- -

MS units in the different centres monitored the patients directly.

A Dutch study reports that, of 86 individuals with MS, 50% had a positive SARS-COV-2 test and that of these, half were hospitalised, 3 required intensive care, and 4 passed away. They found no differences between the disease-modulating treatments used and the course of COVID-19.19

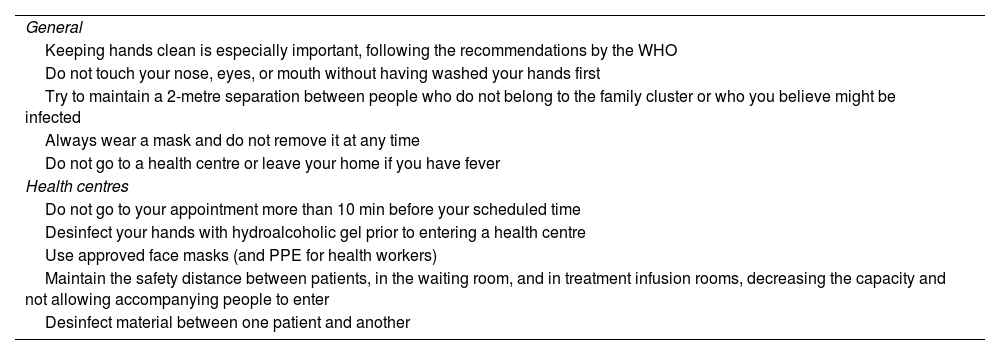

Safety protocols to follow when attending the multiple sclerosis follow-up health centreThe safety protocols included the recommendations for the general population and specific recommendations for MS patients as listed in Table 2.

Hygiene recommendations to protect onself from SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

| General |

| Keeping hands clean is especially important, following the recommendations by the WHO |

| Do not touch your nose, eyes, or mouth without having washed your hands first |

| Try to maintain a 2-metre separation between people who do not belong to the family cluster or who you believe might be infected |

| Always wear a mask and do not remove it at any time |

| Do not go to a health centre or leave your home if you have fever |

| Health centres |

| Do not go to your appointment more than 10 min before your scheduled time |

| Desinfect your hands with hydroalcoholic gel prior to entering a health centre |

| Use approved face masks (and PPE for health workers) |

| Maintain the safety distance between patients, in the waiting room, and in treatment infusion rooms, decreasing the capacity and not allowing accompanying people to enter |

| Desinfect material between one patient and another |

During the confinement period, MS patients were managed by telephone whenever possible. Outbreaks and emergencies were managed face-to-face at the hospital. When confinement ended, patients were telephoned to return to face-to-face consultations.

During the early months of the pandemic, a number of adaptations had to be made:

- -

In the first few months of confinement, initial MS treatment was discontinued in some patients.

- -

In certain centres, drug safety tests, which could be delayed at the doctor’s discretion, were postponed in some centres, and those that were necessary continued to be conducted in the same way in the day hospital. Some patients who had these analyses done in primary care centres had to go to the day hospital because of the difficulty in getting them done at those centres.

- -

In order to minimise hospital visits, patients were scheduled so that they could undergo all tests and see the doctor on the same day; they were also given appointments for intravenous treatments in the day hospital or in the nursing clinic for their remaining treatments. The Pharmacy Service also arranged for the medication to be prepared to be available on the day of the appointment.

- -

In cases of treatment postponement or delay (the first treatment or subsequent cycles), the SEN consensus guidelines20 were followed.

- -

In a number of cases, intravenous cortisone treatment was switched to oral administration. In some hospitals this was already being carried out prior to the epidemic, but in others, it was implemented during confinement.

- -

Home care service was available in some centres and in others, there was even a home hospitalisation service.

- -

Reports were provided to all patients who needed to take time off work or to work remotely from home.

- -

Nursing visits were conducted via telephone.

- -

At the beginning of the pandemic, telephone hours for patients were extended. After the end of the confinement phase, the usual hours were resumed.

An observational study of more than 3000 MS patients in the United States indicates that people at higher risk of acquiring COVID-19 are younger, with lower economic status, and who have to work at face-to-face jobs. Furthermore, 4.4% of patients reported that they had to change their treatment regimens, primarily in the form of delaying treatment infusions, and 15.5% reported interruptions to their rehabilitation sessions.21 In another US study, MS patients reported frequent health care delays and 10% reported changes in immunotherapy administration.22

In Italy, “televisits” have been conducted in MS patients, consisting of remote clinical appointments, via audio-visual connection, with the patient at home. This system was already being used in stroke patients, but it became more widely used in MS patients in Italy during confinement due to the pandemic and proved to be a useful method of care, allowing patients to be cared for when direct person-to-person contact had to be avoided as much as possible.23

Quality of life recommendations and supportRecommendations were provided concerning MS patients’ quality of life. In all centres included in the study, psychological help and counselling was (and continues to be) offered to those who asked for it. Patients were told how they could contact psychologists and the College of Psychologists [who] made a service available to patients, which was also offered by patient associations. Links were provided with recommendations and advice to patients on how to stay mentally active (painting, cooking, reading, listening to music, etc.) and how to avoid receiving toxic information. Advice was also given on how to engage in mental and physical activities as a family. At two of the centres (Seville and Vizcaya), workshops were held via streaming, with the participation of the entire multidisciplinary MS team, for both patients and their relatives.

In a study carried out during confinement of 84 MS patients in the community of Castilla y León, most of the patients were found to maintain physical activity, 34.5% were getting a moderate degree and 33.3% a high degree of physical activity. In addition, belonging to a patient association was found to enhance some beneficial aspects of their health, such as being physically active, having high levels of resilience, and good coping strategies.5

In Italy, the impact of COVID-19 confinement on people with MS has been researched and a negative psychosocial impact has been observed. The pandemic caused significant disruption to usual health and social care services, negatively affecting patients’ health and well-being. Disruptions in care were associated with negative perceptions of disease progression, personal expenses, and caregiver stress. Psychological consequences were related to the disruption of usual psychological support and concerns about the safety of care received.24

Another study (web-based survey of 612 MS patients and 674 controls) found a higher percentage of depression (43.1% vs. 23.1%; p < 0.001), feeling stressed (58% vs. 39.8%; p < 0.001), and lower social support (mean 33 vs. 35; p < .001) in MS patients than in the control population. However, in a secondary analysis, in which the migraine population (318 people) was taken into account, a higher percentage of depression was found among people with migraine than among MS patients (50% vs. 43%; p = 0.04).25

Recommendations and assistance on a number of practical aspects- -

Patients were told how they to contact social workers.

- -

Free home delivery of medication was provided, managed by the pharmacy of the health centres and volunteers.

- -

It became possible for third parties to collect medication (this was already possible at some facilities prior to the pandemic). Some centres also made it possible for medicines to be collected in vehicles, managed by the hospital pharmacy, and delivered by courier (at a cost). Other options included delivering medication to the pharmacy near the patient. The MS unit staff themselves collected the medication in place of the patient in some centres.

- -

Organisations such as Caritas and the Red Cross also provided home medication deliveries.

There is currently an updated Multiple Sclerosis International Federation (MSIF) guideline with recommendations on vaccination against SARS-CoV-226 and several recommendations are also listed on the website of the Toledo Multiple Sclerosis and other neurological diseases Association.27

ConclusionsDuring pandemics, once virus transmission containment measures, effective treatments that require less monitoring and fewer visits to healthcare facilities should ideally be implemented.

During confinement and beyond, MS unit nurses developed and implemented new forms of patient care. Contact between the MS unit and patients was maintained by telephone or telematically. Patients were provided with COVID-19-related information, as well as information on safety and behavioural aspects in case of face-to-face visits to health care facilities. Patients were instructed to inform the MS unit of their situation in the event of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Face-to-face visits, treatments, and medication distribution were adapted. Information was also provided on how to receive psychological support and how to maintain quality of life.

In our experience, nursing consultations in MS units have undergone changes during the pandemic, but the overall impression is that they have not had a major impact on our organisation and that patients have also adapted quickly to these changes. Nevertheless, studies are needed to analyse and quantify these impressions.

Extending opening hours, keeping patients informed by providing links or e-mails, and sharing experiences among the centres that care for these patients are actions to be taken into account in pandemic periods.

FundingThe professional medical writing was funded by the Spanish Society of Neurological Nursing (SEDENE).

Conflict of interestsMercè Lleixa Sardañons has received fees from Bayer, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, Teva, and Merck as a speaker at meetings organised by these same companies.

Montse Artola Ortiz has received fees from Almirall, Biogen Idec, Sanofi Genzyme, and Novartis as a speaker at meetings organised by this pharmaceutical company and has also received support from Almirall, Biogen Idec, Sanofi Genzyme, Teva, Roche, and Merck Serono to attend meetings and conferences.

Noelia Becerril Ríos has received support to attend meetings and congresses and has been a consultant and speaker for Merck, Sanofy, Novartis, Biogen, Bayer, Roche, Teva, and Almirall; she has also received fees from these pharmaceutical companies as a speaker at meetings organised by them.

Guadalupe Cordero Martín has received support from Sanofy Genzyme to attend meetings and conferences and has received fees from Sanofy Genzyme, Novartis, Teva, and Biogen Indec [sic] as a speaker at meetings organised by these pharmaceutical companies.

Ana Hernando Andrés has received support from Merck, Bayer, Biogen, Sanofi Genzyme, Teva, Roche, Novartis, and Almirall to attend meetings and conferences; she has also received funding for educational programmes or training activities from Merck and has received fees from this pharmaceutical company as a speaker at meetings organised by them.

Ana María Lozano Ladero has received support from Merck, Sanofy, Biogen, and Almirall to attend meetings and conferences; she has also received funding for educational programmes or training activities from Merck, Sanofy, and Biogen, and has received fees from these pharmaceutical companies as a speaker at meetings organised by them.

José Ramón Sabroso declares that he has no conflict of interest related to the article.

César Manuel Sánchez Franco has received support to attend meetings/conferences and has received fees as a speaker at meetings organised by the following pharmaceutical companies: Almirall, Biogen, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi; he has been a consultant for the following pharmaceutical companies: Biogen, Merck, Novartis, and Roche.

Beatriz del Río Muñoz has received support from Merck, Novartis, and Sanofi to attend meetings and conferences; has received fees from Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, Teva, Biogen, Almirall, and Roche as a speaker at meetings organised by these pharmaceutical companies; she has received funding for educational programmes or training activities from Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, Biogen, Almirall, and Roche, and she has received support and funding from Novartis and Almirall for research.

The authors would like to thank Ana Moreno Cerro, on behalf of Springer Healthcare Communications, for her assistance in drafting this manuscript. The authors would like to thank M. José Valderas of MERCK S.L.U. for his support in the development of this project.