Fibrinolysis is often used in the treatment of acute coronary syndromes with ST segment elevation (STEMI). Major cardiac outcomes were reduced with antiplatele therapy intensification, but with increased risk of bleeding Our objective was to assess the risk of vascular bleeding in patients undergoing early percutaneous coronary intervention after thrombolysis.

MethodsBetween February 2010 and December 2011, five public emergency rooms in the city of São Paulo and the Emergency Health Care Service (Serviço de Atendimento Móvel de Urgência – SAMU) used tenecteplas (TNK) to treat patients with STEMI. Patients were referred to a single tertiary hospital and were submitted to early cardiacatheterization during hospitalization. All examinations werperformed via the femoral artery and BARC criteria were useto classify bleeding.

ResultsWe evaluated 199 patients, of whom 193 had no bleeding of vascular origin (group 1) and 6 (3%) developed this complication (group 2). The median time between the administration of the fibrinolytic agent and catheterization was 24 hours in group 1 and 14.7hours in group 2. According to BARC criteria, 1 patient had type 3a bleeding (hematoma in the inguinal region with a hemoglobin decrease of 3–5g/dL), 2 patients had type 3b bleeding (1 not related to vascular access and 1 retroperitoneal hematom with a hemoglobin decrease≥5g/dL) and the remaining patients had type 1 bleeding (small inguinal hematomas). Blood transfusions were required in 2 patients. None of the patients died due to vascular complications after the intervention.

ConclusionsIn our study, early catheterization via the femoral artery as part of a pharmaco-invasive strategy, using TNK as a fibrinolytic agent, had a low vascular bleeding rate, comparable to that of elective angioplasties.

Complicações Vasculares em PacientesSubmetidos a Intervenção Coronária Percutânea Precoce por Via Femoral após Fibrinólise com Tenecteplase: Registro de 199 Pacientes

IntroduçãoA fibrinólise é frequentemente utilizada no tratamento das síndromes coronárias com supradesnivelamento do segmento ST (SCCSST). Desfechos cardíacos maiores foram reduzidos com a intensificação do tratamento antiplaquetário, porém com aumento do risco de sangramento. Nosso objetivo foi avaliar o risco de sangramentos de origem vascular em pacientes submetidos a intervenção coronária precoce pós–trombólise.

MétodosEntre fevereiro de 2010 e dezembro de 2011, 5 prontos-socorros municipais da cidade de São Paulo e o Serviço de Atendimento Móvel de Urgência (SAMU) utilizaram tenecteplase (TNK) para tratamento de pacientes com SCCSST. Os pacientes foram encaminhados a um único hospital terciário e submetidos a cateterismo cardíaco precoce durante a internação. Todos os exames foram realizados por via femoral e os critérios do BARC foram utilizados para a classificação dos sangramentos.

ResultadosForam avaliados 199 pacientes, dos quais 193 não apresentaram sangramento de origem vascular (grupo 1) e 6 (3%) evoluíram com essa complicação (grupo 2). A mediana de tempo entre a administração do fibrinolítico e o cateterismo foi de 24 horas no grupo 1 e de 14,7 horas no grupo 2. Segundo os critérios do BARC, 1 paciente apresentou sangramento do tipo 3a (hematoma em região inguinal com queda de hemoglobina de 3–5g/dL), 2 pacientes apresentaram sangramento do tipo 3b (1 não relacionado ao acesso vascular e 1 hematoma de retroperitônio, com queda de hemoglobina≥5g/dL), e os demais apresentaram sangramentos do tipo 1 (pequenos hematomas em região inguinal). Nesse grupo foram necessárias duas hemotransfusões. Nenhum paciente teve óbito relacionado à complicação vascular pós-intervenção.

ConclusõesEm nosso estudo, a cateterização precoce via femoral como parte de uma estratégia fármaco-invasiva, utilizando TNK como fibrinolítico, apresentou baixa taxa de sangramentos de origem vascular, comparável à das angioplastias eletivas.

The coronary syndromes that course with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) remain an important cause of morbidity and mortality. In this group of patients, the prognosis and incidence of major adverse events are directly associated with the interval between symptom onset and flow restoration in the coronary lesion; reperfusion therapy remains as the basis of treatment.

Fibrinolytic agents initiated the ‘era of reperfusion’, promoting the lysis of the occlusive thrombus and achieving the reduction of infarcted area, ventricular function improvement and increased survival. 1 Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was later established as the method of choice for the restoration of antegrade coronary flow, providing higher rates of reperfusion (90% vs. 50% with fibrinolytic agents) and additional reductions in major cardiovascular outcomes. 2,3 The combined use of these strategies follows restricted indications in scenarios in which it was proven to be safe and effective: PCI after fibrinolysis without success (rescue) and early PCI between three and 24 hours after successful chemical reperfusion (drug-invasive strategy). 4

Additionally, the use of modern antithrombotic pharmacotherapy (oral platelet antiaggregants, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, and antithrombotic agents) has resulted in additional reductions in cardiovascular mortality and the recurrence of ischaemic events. 5 However, the indubitable benefit of these associations is counterbalanced by the inherent increased risk of bleeding, the major non-cardiac complication in patients treated for acute myocardial infarction (AMI). 6

Hemorrhagic complications, whether or not related the vascular puncture site, are associated with a higher incidence of cerebrovascular events, AMI, intrastent thrombosis, and death, 7 and they currently occur with similar frequency to that of ischemic complications. The reduction in bleeding episodes translates into improved survival, shorter hospital stay, and lower costs, justifying the current emphasis on the identification of predisposing factors and prophylaxis of bleeding episodes. 7

In this study, patients diagnosed with STEMI who were treated with fibrin-specific thrombolytic therapy and who underwent early coronary angiography and PCI via the femoral artery were evaluated for the incidence of bleeding of vascular origin.

METHODSPatients and proceduresThis was an observational study with prospective data collection, conducted between November of 2009 and January of 2012. In this study, 199 patients who met the diagnostic criteria for AMI, with electrocardiographic evidence of ST-segment elevation or left bundle branch block (new or presumably new), were initially treated at a network of municipal emergency departments or the Mobile Emergency Service (Serviço de Atendimento Móvel de Urgência – SAMU) and then transferred to Hospital São Paulo, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP). These patients were treated with tenecteplase (TNK) and underwent early coronary angiography and PCI when necessary, exclusively through the femoral artery.

Patients were consecutively included in this study, divided into two groups (according to the presence or absence of bleeding of vascular origin) and evaluated for the incidence and predictors of these complications. All patients received loading doses of 300mg of acetylsalicylic acid and 300mg or 600mg of clopidogrel during the primary care or upon arrival at the tertiary hospital. The antithrombin agent of choice during PCI was unfractionated heparin at a dose of 100 U/kg (or 70 U/kg in those treated with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors). The size of the arterial sheaths used was left to the surgeon’s discretion. Patients undergoing PCI received only bare-metal stents, which were provided by the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde – SUS).

Hemostasis after removing the introducer was performed exclusively by manual compression, respecting an interval of four to six hours after administration of unfractionated heparin in the emergency room.

DefinitionsBleeding episodes were classified according to the criteria established by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) 7 in 2011 (Table 1).

Classification of the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC)

| Type 0 | Absence of bleeding. |

| Type 1 | Minor bleeding, not requiring medical attention or hospitalisation. |

| Type 2 | Any sign of bleeding that does not meet the criteria of types 3, 4, or 5, but meets at least one of the following criteria: |

| - need for non-surgical medical intervention; | |

| - need for hospitalisation or increased level of care; | |

| - need for immediate clinical evaluation. | |

| Type 3 | |

| Type 3 a | Bleeding associated with a decrease in haemoglobin of 3-5g/dL or need for blood transfusion. |

| Type 3b | Bleeding associated with a decrease in haemoglobin>5g/dL, cardiac tamponade, need for surgical control of bleeding (except dental/nasal/skin/haemorrhoid), or need for vasoactive drugs. |

| Type 3c | Intracranial bleeding (except for micro-bleeding or haemorrhagic transformation; includes intraspinal bleeding); subcategories confirmed by autopsy, imaging, or lumbar puncture; or intraocular bleeding with vision impairment. |

| Type 4 | Bleeding related to coronary artery bypass: perioperative intracranial bleeding within 48 hours; reoperation after closure of sternotomy to control bleeding; transfusion>5 packed red blood cells within a 48-hour period; chest tube bleeding>2L in 24 hours. |

| Type 5 | Fatal bleeding. |

| Type 5 a | Probable fatal bleeding: clinical suspicion not confirmed by autopsy or imaging. |

| Type 5b | Definitive fatal bleeding: active bleeding or confirmed by autopsy or imaging methods. |

Obesity was defined as body mass index (BMI) > 35kg/m2 and chronic renal disease by creatinine clearance≤60mL/min, estimated by the Cockroft-Gault equation. Peripheral vascular disease, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension were identified as part of the pathological history or were diagnosed during hospitalization.

Statistical analysisThe prospectively collected data were stored in a spreadsheet database (Excel ®, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, USA) and submitted to statistical analysis using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), release 14.0.

Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations, and categorical variables were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. Categorical variables were compared by Fisher’s exact test or the chi-squared test, and continuous variables were compared by Student’s t-test. For variables without normal distribution, the median was compared between groups.

A multivariate logistic regression model, adjusted for the interaction between age and diabetes mellitus and that between diabetes mellitus and chronic renal disease, was used to identify possible independent predictors of hemorrhagic vascular complications. Odds ratios (ORs) and their confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated to quantify the effects. The variables used in this model were the clinical variables age, gender, diabetes, arterial hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, chronic renal disease, dyslipidaemia, and obesity. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant for all analyses.

RESULTSOf the 199 patients evaluated, 193 (97%) had no bleeding of vascular origin (group 1), and six patients (3%) had such complications (group 2). In 19 patients (9%), the intervention was indicated after thrombolytic therapy failure (rescue PCI); of these patients, only one had hematoma at the puncture site and a decrease in hemoglobine of 4.1g/dL. The other patients underwent elective coronary angiography at a mean of 19±4 hours (ranging from three hours to 3.5days) after thrombolytic therapy. The median time between the administration of the fibrinolytic agent and PCI was 24 hours in group 1 and 14.7hours in group 2.

Regarding clinical characteristics, group 2 patients were older (57±11 years vs. 69±11.7years, P=0.01) and had a higher prevalence of chronic renal disease (6% vs. 67%, P=0.01). The prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity and peripheral vascular disease was similar between groups (Table 2).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients undergoing fibrinolysis and catheterisation/early percutaneous coronary intervention

| Group 1(n=193) | Group 2(n=6) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender, n (%) | 133 (70) | 4 (67) | 0.97 |

| Age, years | 57±11 | 69±11.7 | 0.01 |

| Systemic arterial hypertension, n (%) | 124 (64) | 5 (83) | 0.33 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 48 (25) | 1 (17) | 0.64 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 15 (8) | 1 (17) | 0.43 |

| Chronic renal disease, n (%) | 12 (6) | 4 (67) | 0.01 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 69 (36) | 1 (17) | 0.33 |

n=number of patients

Only one patient in group 2 received glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors during the procedure. 6-F and 7-F sheaths were used, at the surgeon’s discretion. In group 1, 7-F sheaths were used in 16 of 193 patients (8%), compared to four of the six patients (67%) in group 2, and a significant increase in the risk of bleeding complications was observed with the use of larger sheaths (P=0.001).

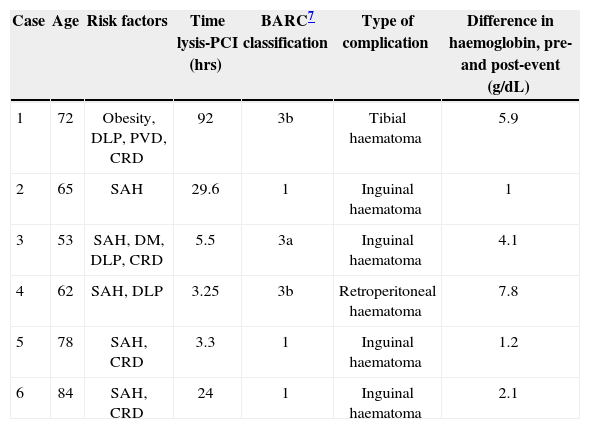

In group 2, three patients experienced bleeding related to an arterial puncture site categorised as type 1. The other three patients had more severe bleeding: one had a large inguinal hematoma associated with a decrease in hemoglobin of 4.1g/dL; the second patient had a hematoma in the pretibial region with a decrease in hemoglobin of 5.9g/dL, possibly related to trauma in the days prior to AMI; the last patient had a retroperitoneal hematoma with a decrease in hemoglobin of 7.8g/dL (Table 3).

Characteristics of patients with bleeding of vascular origin in percutaneous coronary intervention after thrombolysis

| Case | Age | Risk factors | Time lysis-PCI (hrs) | BARC7 classification | Type of complication | Difference in haemoglobin, pre-and post-event (g/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 72 | Obesity, DLP, PVD, CRD | 92 | 3b | Tibial haematoma | 5.9 |

| 2 | 65 | SAH | 29.6 | 1 | Inguinal haematoma | 1 |

| 3 | 53 | SAH, DM, DLP, CRD | 5.5 | 3a | Inguinal haematoma | 4.1 |

| 4 | 62 | SAH, DLP | 3.25 | 3b | Retroperitoneal haematoma | 7.8 |

| 5 | 78 | SAH, CRD | 3.3 | 1 | Inguinal haematoma | 1.2 |

| 6 | 84 | SAH, CRD | 24 | 1 | Inguinal haematoma | 2.1 |

BARC=Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; DLP=dyslipidaemia; DM=diabetes mellitus; PVD=peripheral vascular disease; SAH=systemic arterial hypertension; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; CRD=chronic renal disease.

Only two patients in group 2 (patients 3 and 4, Table 3) required transfusion of blood products. None of the patients died of vascular complications; however, there was one death in group 2 resulting from cardiogenic shock (patient 3).

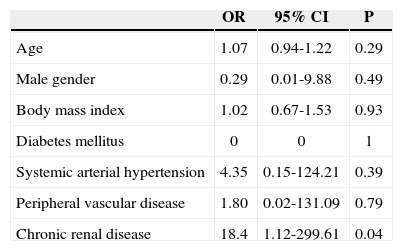

In multivariate regression analysis, after correcting for the interaction between diabetes mellitus and chronic renal disease, the only variable that remained associated with the presence of hemorrhagic vascular complications was chronic renal disease (OR: 18.4; 95% CI: 1.12-299.61; P=0.04) (Table 4).

Results of the logistic regression to determine the risk of bleeding of vascular origin in percutaneous coronary intervention after thrombolysis

| OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.07 | 0.94-1.22 | 0.29 |

| Male gender | 0.29 | 0.01-9.88 | 0.49 |

| Body mass index | 1.02 | 0.67-1.53 | 0.93 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Systemic arterial hypertension | 4.35 | 0.15-124.21 | 0.39 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.80 | 0.02-131.09 | 0.79 |

| Chronic renal disease | 18.4 | 1.12-299.61 | 0.04 |

95% CI=95% confidence interval; OR=odds ratio.

Current recommendations for PCI after fibrinolytic therapy are rescue PCI (class IIa, level of evidence B, in the ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines of 2011, and class I, level of evidence A, in the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology, 2012); elective and systematic PCI performed between three and 24 hours after effective fibrinolysis (class IIa, level of evidence A, ACC/AHA/ SCAI guidelines, and class I, level of evidence A, in the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology); and PCI in patients with evidence of clinical ischemia or in functional tests (class IIa, level of evidence B, in the ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines). 4,8

In stable patients submitted to successful chemistry reperfusion, the use of systematic and early invasive stratification within the first 24 hours (drug-invasive strategy) has been associated with reduced incidences of reinfarction and recurrent ischemic events without significantly increasing the rates of vascular complications. However, very early coronary angiography (less than three hours after administration of thrombolytic agent) results in high rates of ischemic and hemorrhagic complications and should be reserved for cases of treatment failure. 4,9−11

Ample evidence supports the use of a drug-invasive approach. In the Trial of Routine ANgioplasty and Stenting after Fibrinolysis to Enhance Reperfusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction (TRANSFER-AMI), 1,030 patients with high-risk STEMI were randomized to urgent PCI performed four hours after administration of TNK or standard treatment (subsequently transferred to elective coronary angiography or rescue PCI, if necessary). The composite endpoint of death, reinfarction, recurrent ischemia, heart failure or shock at 30 days occurred in 10.6% of the early PCI group and in 16.6% of the standard treatment group (OR: 0.537; 95% CI: 0.368-0.783; P=0.0013). 12 There was no significant increase in the rate of bleeding in the early PCI group. In the Combined Abciximab Reteplase Stent Study in Acute Myocardial Infarction (CARESS-in-AMI), 600 patients were randomized to early angiography three hours after fibrinolytic therapy or standard therapy. The combined endpoint of death, reinfarction and refractory ischemia at 30 days occurred in 4.4% of the early PCI group and in 10.7% of the standard group (P=0.004); and rescue PCI was necessary in 30.3% of cases. Minor bleeding occurred more frequently in the early PCI group (10.8% vs. 4%, P=0.002), but there was no significant increase in major bleeding episodes (3.4% vs. 2.3%, P=0.47). 13 In the Grupo de Análisis de la Cardiopatía Isquémica Aguda (GRACIA-2) study, the use of TNK followed by systematic PCI within a range of three to 12 hours (mean 4.6hours) was not found to be inferior to primary PCI regarding the major outcomes, and there was no significant increase in the rate of bleeding. 14

The association between antithrombotic drugs and revascularization procedures has proven effective in the prevention of recurrent ischemic events and death in acute coronary syndromes (ACS). This combination is, however, associated with an increased risk of bleeding and vascular complications, especially in older patients, those using multiple antithrombotic therapy, and those submitted to early revascularization. 15 In highrisk subgroups, the prevalence of major hemorrhagic complications during treatment reaches 5%, close to that of ischaemic events.

Factors such as advanced age, female gender, chronic renal disease, low BMI, and the need for invasive procedures have been strongly implicated as predictors of vascular complications. Elderly patients present with progressive deposition of amyloid and collagen in the arterial tunica media, resulting in vascular frailty and greater tendency to vascular complications. Women have lower BMI and lower creatinine clearance than men and are therefore more susceptible to relatively higher doses of antithrombotic agents and bleeding. Additional contributing factors to vascular complications are smaller vascular diameter and possible differences in response to antithrombotics. 6 In turn, patients with chronic nephropathy more often exhibit a pattern of diffuse vascular disease, in addition to being more often exposed to higher (uncorrected) doses of drugs. The higher prevalences of anemia (reduced synthesis of erythropoietin) and platelet dysfunction in these patients also contribute to these complications.

When analysing the impact of bleeding complications on the prognosis of patients with ACS, Eikelboom et al. 16 demonstrated that the occurrence of major bleeding was associated with a five-fold increased risk of death at 30 days and that one in three patients who had bleeding episodes and died developed an AMI during hospitalization. Ndrepepa et al. 5 analysed 12,459 patients undergoing PCI who were enrolled in six randomized studies on the correlation between bleeding episodes and mortality in one year. They found that bleeding episodes classified as BARC≥2 were associated with significantly increased mortality in one year (OR: 2.72; 95% CI: 2.03-3.63).

Several hypotheses have been posited to justify this association between bleeding and major cardiovascular outcomes. These complications are possibly associated with hypotension, platelet activation, and decreased tissue oxygen supply (hypoperfusion or decreased haemoglobin) due to bleeding and the deleterious effects of blood transfusion. Additionally, the presence of bleeding requires the suspension of several drugs with proven benefits in increasing survival, such as antiplatelets and beta blockers, predisposing the patient to intrastent thrombosis, AMI, recurrent angina, acute ischaemic stroke, and death.16

Most bleeding episodes in patients with ACS undergoing PCI are iatrogenic, attributable to arterial puncture (more frequent in the femoral artery), ranging from a small subcutaneous haematoma free of clinical relevance to a fatal retroperitoneal haematoma. The femoral artery remains the most widely used means of access for interventional procedures. The alternative use of radial access has provided increased safety and comfort for patients. 6

Jolly et al., 17 in a randomized clinical trial comparing radial vs. femoral access in patients with ACS undergoing PCI, found no differences between the two groups in terms of major cardiovascular outcomes, but the radial approach was safer, with lower rates of vascular complications.

In the RadIal Vs femorAL access for coronary intervention (RIVAL) study, 18 published in 2011, 7,021 patients from 32 countries with a diagnosis of ACS were randomized to coronary angiography with possible intervention by radial access vs. femoral access. There were no differences regarding the primary composite endpoint of death, AMI, cerebrovascular disease and major bleeding (not related to revascularization) at 30 days (3.7% vs. 4%, P=0.5). However, radial access significantly reduced the secondary endpoint of complications related to vascular access (P < 0.001). In the Radial versus Femoral Randomized Investigation in ST-segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome (RIFLE-STEACS) study, 19 published in 2012, 1001 patients with STEMI undergoing primary or rescue PCI were randomized to radial vs. femoral access. The primary outcome analysis, a combination of death, cerebrovascular disease, acute myocardial infarction, target vessel revascularization, and bleeding, was significantly lower in the radial group (13.6% vs. 21%, P=0.003). Bleeding episodes occurred in 10% of patients, with the highest incidence in the femoral group (12.2% vs. 7.8%, P=0.026). This difference was primarily due to a lower rate of bleeding related to puncture site in the radial group (2.6% vs. 6.8%, P=0.002). In the evaluation of secondary outcomes, there was a significant reduction in mortality at 30 days in the radial group (5.2% vs. 9.2%, P=0.002). In a meta-analysis that included 761,919 patients from 76 studies (15 randomized and 61 observational studies) comparing radial and femoral routes for PCI, Bertrand et al. 20 demonstrated significant reductions of 78% of bleeding and 80% of blood transfusions with the use of radial access. It is noteworthy that these studies were conducted in institutions with extensive experience with radial access, a situation that cannot always be reproduced, especially in laboratories where specialists are educated and trained and individual experience varies with training. In the RIVAL study, centers with higher volumes of PCI through the radial access route obtained a greater benefit. These centers had lower rates of crossover to femoral access, of major vascular complications, and of the composite outcome of death, AMI, and cerebrovascular disease. This effect was not reproduced in the centers with smaller volumes.

When using the femoral approach, the use of vascular occlusion devices has translated into a greater impact on the prevention of major bleeding episodes, in spite of substantially increased costs. In the present study, hemostasis was achieved by manual compression in all cases.

Bleeding of undetermined origin, detected by decreases in hemoglobin and hematocrit (with or without blood transfusion), is also relevant. In one randomized study, this type of event accounted for almost half of the bleedings not associated with vascular access. Verheugt et al. 15 demonstrated that bleedings not associated with the puncture site cause a two-fold higher annual mortality than that observed for arterial-access bleedings (and four times higher than in individuals without bleeding).

The present study evaluated patients undergoing early drug-invasive strategy through femoral access, and a low incidence of hemorrhagic vascular complications was observed (3%), similar to that observed in elective interventions, 21 demonstrating the safety of this approach. In their analysis of 4,595 patients under going PCI, either elective or emergency, in which 95% of the procedures were performed via the femoral artery with 6-F sheaths, Zanatta et al. 21 observed a vascular complication rate of 3.3%.

When comparing the groups, although the median time between fibrinolytic use and the percutaneous procedure was higher in group 1 (24hours vs. 14.7hours), both were within the safe range of three and 24 hours, and therefore there was no evidence of an increase in major bleeding complications with previous use of fibrinolytics. 4,9

In 83% (5/6) of cases in this series, complications were related to vascular puncture site, in accordance with the literature. Half of the bleeding complications were categorized as BARC type 1, and no deaths from vascular causes were observed. In fact, BARC type 1 bleeding episodes have good prognosis, with mortality at 30 days and one year similar to that found in patients who have not experienced bleeding. 22 In a patient classified as BARC type 3b, the occurrence of extensive hematoma in the pretibial region was not associated with the vascular puncture and was most likely caused by closed vascular trauma that occurred before the fibrinolysis, which resulted in a decrease in haemoglobin of 5.9g/dL, but with no clinical repercussion or need for blood transfusion (prior haemoglobin of 16.3g/dL).

Only one death occurred in group 2, in a patient admitted with extensive anterior STEMI who developed cardiogenic shock, a condition that, alone, causes high morbidity and mortality. Early angiography (5.5hours), as rescue therapy, evidenced an acute occlusion in the left main coronary artery, and a PCI was immediately performed using an intra-aortic counterpulsation balloon through the femoral artery. This patient had extensive bleeding at the puncture site, with a decrease in haemoglobin of 4.1g/dL, which was subsequently controlled with blood transfusion and vasopressor drugs. The patient progressed to death secondary to refractory cardiogenic shock two days after the intervention.

In the bleeding group, the greater number of elderly patients and patients with chronic nephropathy were identified as possible predictors of vascular complications and bleeding. After the multivariate analysis, only chronic renal disease remained a significant and independent risk factor for these conditions. Characteristics repeatedly associated with increased vascular complications in the literature, such as female gender and low BMI, were not identified in the present study, possibly because of the small sample size.

Study limitationsThe present study had the following limitations: its retrospective and observational nature; its performance in a single centre, which is a training and teaching facility in interventional cardiology; the small sample size; and the lack of late follow-up. The non-inclusion of procedure-related variables (sheath size, procedure time, use of intra-aortic balloon) and the small number of primary outcomes (six events) represented limiting factors in the multivariate analysis, which was performed to identify possible predictors for such events.

Although this center meets the recommendation for early catheterization (within 24 hours), logistic complications may delay the implementation of the procedure. In the present study, two patients with vascular bleeding underwent the procedure after the initial period of 24 hours.

The present results do not necessarily apply to populations using other fibrinolytic agents.

CONCLUSIONSIn the present study, early catheterization via femoral access as part of a drug-invasive strategy, using TNK as a fibrinolytic agent, showed a low rate of bleeding of vascular origin, comparable to that of elective angioplasties, in agreement with several multicenter studies and based on current guidelines.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.