Despite the close association between smoking and atherosclerotic disease development, little is known about the clinical characteristics and outcomes related to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in smokers with acute coronary syndrome in Brazil. This study aimed to analyze the clinical, angiographic, and procedural profile, in addition to in-hospital outcomes, in smokers and non-smokers with acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation (STEMI) submitted to primary or rescue PCI.

MethodsCross-sectional study of the Central Nacional de Intervenc¿ões Cardiovasculares (CENIC) registry between 2006 and 2016. The study population included patients aged ≥ 18 years who presented with STEMI and were submitted to primary or rescue PCI.

ResultsA total of 20,319 patients were included, of whom 6,880 (34.4%) were smokers. The group of smokers was significantly younger, male, and with a lower prevalence of comorbidities. At angiography, smokers showed greater complexity, with a higher prevalence of thrombi, long lesions or TIMI flow 0/1. During the procedure, smokers received a lower proportion of drug-eluting stents and thrombus aspiration was more frequent, as well as procedural success (94.2% vs. 92.1%; p < 0.0001). In the univariate analysis, smokers showed lower mortality (2.9% vs. 4.5%; p < 0.0001) and fewer major adverse cardiac events (3.3% vs. 4.8%; p < 0.0001). However, after multivariate analysis, smoking was not associated with a lower risk of mortality.

ConclusionsAlthough the clinical outcomes associated with the PCI were favorable to smokers, the multivariate analysis did not show a protective effect of smoking. Such results are due to differences in clinical and angiographic characteristics between smokers and non-smokers.

Apesar da estreita relação do tabagismo com o desenvolvimento da doença aterosclerótica, pouco se sabe sobre as características clínicas e os desfechos relacionados à intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP) em tabagistas com síndrome coronariana aguda no Brasil. O objetivo deste estudo foi analisar o perfil clínico, angiográfico e do procedimento, além de desfechos hospitalares, em pacientes tabagistas e não tabagistas com infarto agudo do miocárdio com supradesnivelamento do segmento ST (IAMCST) submetidos à ICP primária ou de resgate.

MétodosEstudo transversal do registro da Central Nacional de Intervenc¿ões Cardiovasculares (CENIC) entre 2006 e 2016. A populac¿ão do estudo incluiu pacientes com idade ≥ 18 anos que apresentassem IAMCST submetidos à ICP primária ou de resgate.

ResultadosForam incluídos 20.319 pacientes, dos quais 6.880 (34,4%) eram tabagistas. O grupo de pacientes tabagistas era significativamente mais jovem, do sexo masculino e com menor prevalência de comorbidades. À angiografia, os tabagistas apresentaram maior complexidade, com maior prevalência de trombos, de lesões longas ou fluxo TIMI 0/1. Durante o procedimento, os tabagistas receberam stent farmacológico em menor proporção e a tromboaspiração foi mais frequente, bem como o sucesso do procedimento (94,2% vs. 92,1%; p < 0,0001). Na análise univariada, pacientes tabagistas apresentaram menor mortalidade (2,9% vs. 4,5%; p < 0,0001) e menos eventos cardíacos adversos maiores (3,3% vs. 4,8%; p < 0,0001). No entanto, após análise multivariada, o tabagismo não se associou a menor risco de mortalidade.

ConclusõesEmbora os desfechos clínicos associados à ICP tenham sido favoráveis aos pacientes tabagistas, a análise multivariada não demonstrou efeito protetor do tabagismo. Tais resultados são devidos às diferenças encontradas nas características clínicas e angiográficas entre pacientes tabagistas e não tabagistas.

Cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of death,1 and smoking is considered the main modifiable risk factor for these diseases, accounting for one in every three deaths.2 Tobacco smoking is associated with an increased risk of death and other unfavorable outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS),3 in addition to changes in the lipid profile, generation of reactive oxygen species, platelet activation, and endothelial dysfunction, favoring the atherogenic process. Moreover, the risk is multiplied by four when smoking is associated with other factors, such as dyslipidemia or arterial hypertension.4

Smoking leads to endothelial damage and cell dysfunction. Its effects on the circulation significantly alter the endothelium hemostatic balance, resulting in atherosclerosis and its thrombotic complications. Furthermore, the components of the cigarette smoke reduce the blood's ability to carry oxygen and increase the physiological demands of the myocardium.2 The cardiovascular risk attributable to smoking increases with the number of smoked cigarettes and duration of smoking; nonetheless, even exposure to low levels of cigarette smoke or secondhand smoke can be harmful.

However, the habit of smoking has been associated in some studies with a protective effect, in which smokers submitted to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) showed lower mortality rates in the short term – the so-called smoking paradox. Many studies on the subject have been conducted over the years, and there is now solid scientific evidence showing there is no protective effect of smoking in these patients.5,6 Despite the close association between smoking and the development of atherosclerotic disease, little is known about the clinical profile and outcomes related to PCI in smokers with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in the Brazilian population. Thus, this study aimed to analyze the clinical, angiographic, and procedural profile, in addition to in-hospital outcomes, in smokers and non-smokers with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) who underwent primary or rescue PCI in Brazil.

MethodsStudy design and sampleA cross-sectional study was performed in the Central Nacional de Intervenções Cardiovasculares (CENIC portuguese for National Center for Cardiovascular Interventions) registry of Sociedade Brasileira de Hemodinâmica e Cardiologia Intervencionista (SBHCI portuguese for Brazilian Society of Hemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology) between 2006 and 2016. Data from the database were prospectively collected using standardized forms and stored in a computerized registry. Data from patients with a diagnosis of STEMI submitted to PCI from the CENIC registry were retrospectively analyzed. The study population included patients aged ≥ 18 years who presented with STEMI and were submitted to primary or rescue PCI.

Patient diagnosis and management were carried out according to the specific routines of each collaborating center linked to the SBHCI.

Statistical analysisThe chi-squared test and the analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used for the comparison of categorical and continuous variables, respectively. When necessary, Fisher's exact test or the likelihood ratio test was used. Fisher's exact test (2 × 2 table) or the likelihood ratio test (m × n table, where m and/or n is greater than two categories) was carried out when at least 20% of the expected values were < 5. To verify the influence of the variables of interest in relation to mortality, a simple logistic regression model was used to evaluate death in relation to different independent variables. Additionally, multiple logistic regression was performed using the forward selection method to determine the independent variables that best explain the occurrence of death. Variables with large occurrences of missing data were disregarded in the multiple logistic regression analysis (left ventricular dysfunction and collateral circulation). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistical significant.

ResultsAt the cut-off date, the registry included 176,780 patients and a total of 191,727 procedures; 20,013 patients were selected and analyzed, resulting in 20,310 procedures, with 23,951 treated vessels.

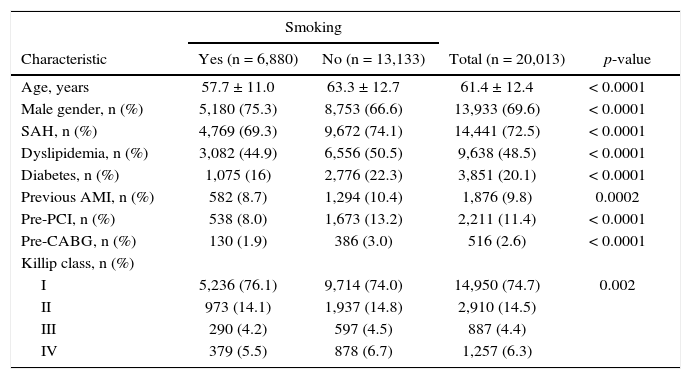

The mean age of the cohort was 61.4 ± 12.4 years, and 20.1% of the patients had diabetes. Patients who were smokers were approximately 5 years younger than non-smokers, with a higher proportion of males, and a lower prevalence of risk factors or history of a previous coronary artery event. The other demographic and clinical characteristics of smokers and non-smokers are shown in Table 1.

Clinical characteristics.

| Smoking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Yes (n = 6,880) | No (n = 13,133) | Total (n = 20,013) | p-value |

| Age, years | 57.7 ± 11.0 | 63.3 ± 12.7 | 61.4 ± 12.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 5,180 (75.3) | 8,753 (66.6) | 13,933 (69.6) | < 0.0001 |

| SAH, n (%) | 4,769 (69.3) | 9,672 (74.1) | 14,441 (72.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 3,082 (44.9) | 6,556 (50.5) | 9,638 (48.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 1,075 (16) | 2,776 (22.3) | 3,851 (20.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Previous AMI, n (%) | 582 (8.7) | 1,294 (10.4) | 1,876 (9.8) | 0.0002 |

| Pre-PCI, n (%) | 538 (8.0) | 1,673 (13.2) | 2,211 (11.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Pre-CABG, n (%) | 130 (1.9) | 386 (3.0) | 516 (2.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Killip class, n (%) | ||||

| I | 5,236 (76.1) | 9,714 (74.0) | 14,950 (74.7) | 0.002 |

| II | 973 (14.1) | 1,937 (14.8) | 2,910 (14.5) | |

| III | 290 (4.2) | 597 (4.5) | 887 (4.4) | |

| IV | 379 (5.5) | 878 (6.7) | 1,257 (6.3) | |

SAH: systemic arterial hypertension; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft.

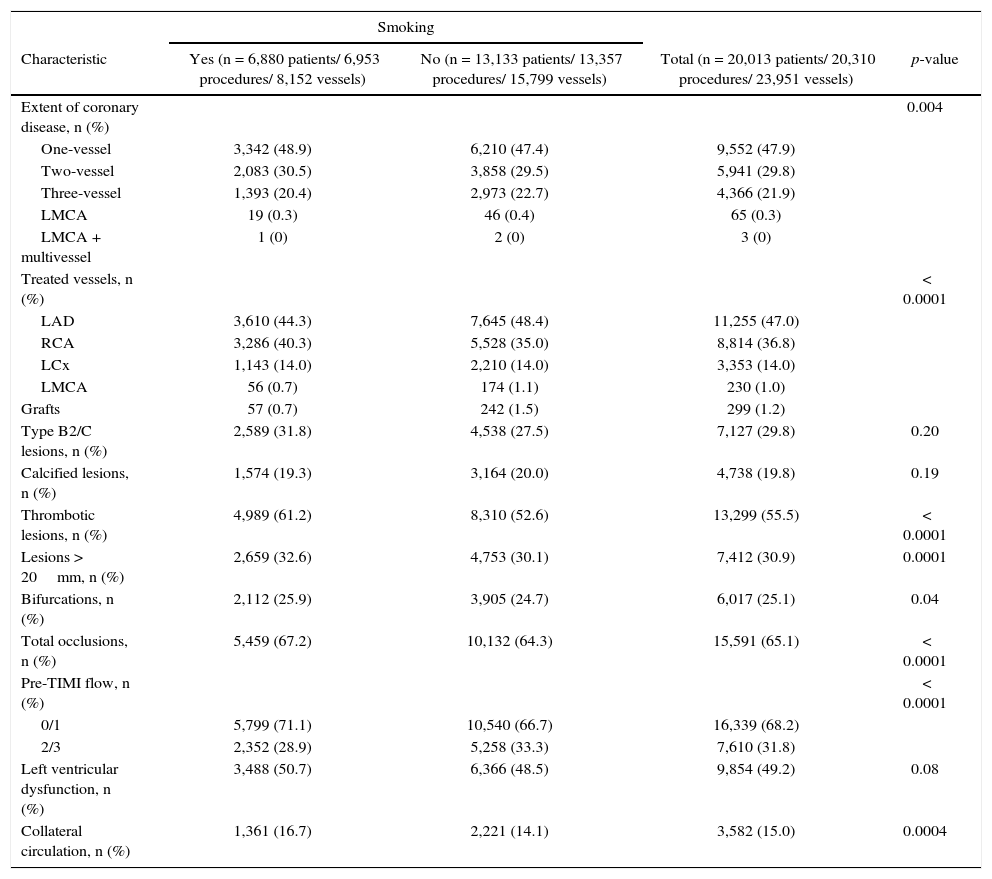

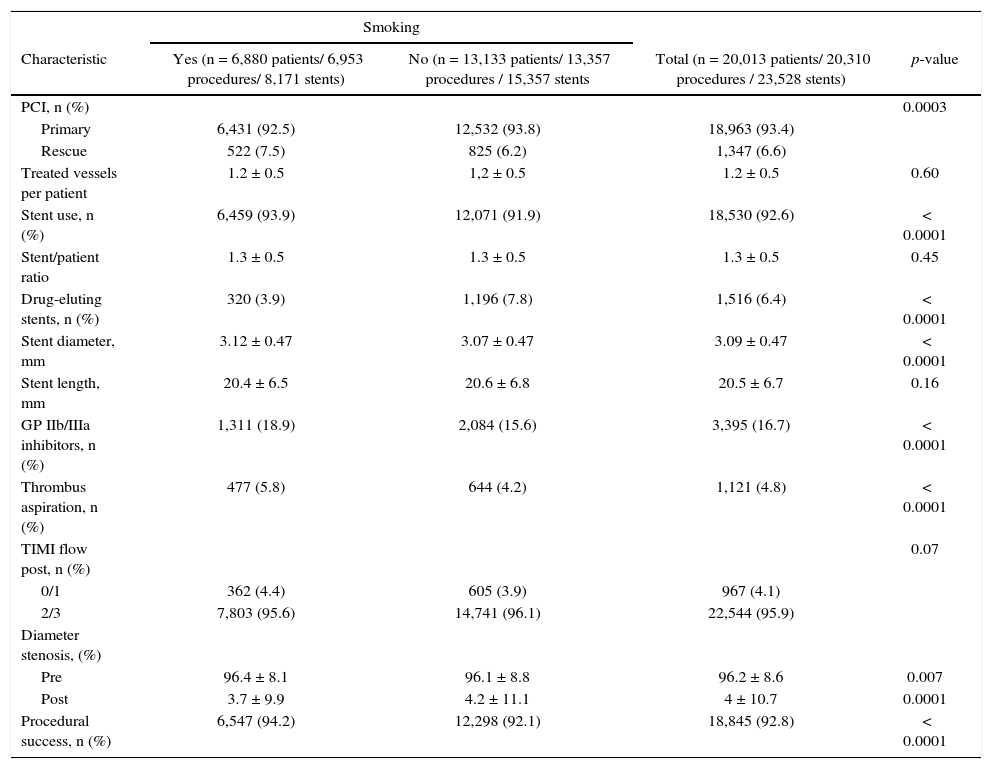

Most patients had one-vessel disease (47.9%), and the most frequently treated vessel was the left anterior descending artery (47%). Thrombotic lesions (61.2% vs. 52.6%; p < 0.0001), long lesions (32.6% vs. 30.1%, p = 0.0001), and bifurcation lesions (25.9% vs. 24.7%; p = 0.04) were more frequently found in smokers. Collateral circulation was observed more frequently in smokers (16.7% vs. 14.1%; p = 0.0004), as well as Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow 0/1 (71.1% vs. 66.7%, p < 0.0001). The other angiographic features are described in Table 2. The mean number of treated vessels and stents per patient was 1.2 ± 0.5 and 1.3 ± 0.5, respectively, in the entire cohort. Primary PCI was performed in 92.5% vs. 93.8% and rescue PCI in 7.5% vs. 6.2% of smokers and non-smokers, respectively (p = 0.0003). During the procedure, the group of smokers received drug-eluting stents at a lower proportion (3.9% vs. 7.8%; p < 0.0001) and thrombus aspiration was more frequent (5.8% vs. 4.2%; p < 0.0001), as well as the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (18.9% vs. 15.6%, p < 0.0001). Procedural success was more frequent among smokers (94.2% vs. 92.1%, p < 0.0001). Other characteristics of the procedures are described in Table 3.

Angiographic characteristics.

| Smoking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Yes (n = 6,880 patients/ 6,953 procedures/ 8,152 vessels) | No (n = 13,133 patients/ 13,357 procedures/ 15,799 vessels) | Total (n = 20,013 patients/ 20,310 procedures/ 23,951 vessels) | p-value |

| Extent of coronary disease, n (%) | 0.004 | |||

| One-vessel | 3,342 (48.9) | 6,210 (47.4) | 9,552 (47.9) | |

| Two-vessel | 2,083 (30.5) | 3,858 (29.5) | 5,941 (29.8) | |

| Three-vessel | 1,393 (20.4) | 2,973 (22.7) | 4,366 (21.9) | |

| LMCA | 19 (0.3) | 46 (0.4) | 65 (0.3) | |

| LMCA + multivessel | 1 (0) | 2 (0) | 3 (0) | |

| Treated vessels, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| LAD | 3,610 (44.3) | 7,645 (48.4) | 11,255 (47.0) | |

| RCA | 3,286 (40.3) | 5,528 (35.0) | 8,814 (36.8) | |

| LCx | 1,143 (14.0) | 2,210 (14.0) | 3,353 (14.0) | |

| LMCA | 56 (0.7) | 174 (1.1) | 230 (1.0) | |

| Grafts | 57 (0.7) | 242 (1.5) | 299 (1.2) | |

| Type B2/C lesions, n (%) | 2,589 (31.8) | 4,538 (27.5) | 7,127 (29.8) | 0.20 |

| Calcified lesions, n (%) | 1,574 (19.3) | 3,164 (20.0) | 4,738 (19.8) | 0.19 |

| Thrombotic lesions, n (%) | 4,989 (61.2) | 8,310 (52.6) | 13,299 (55.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Lesions > 20mm, n (%) | 2,659 (32.6) | 4,753 (30.1) | 7,412 (30.9) | 0.0001 |

| Bifurcations, n (%) | 2,112 (25.9) | 3,905 (24.7) | 6,017 (25.1) | 0.04 |

| Total occlusions, n (%) | 5,459 (67.2) | 10,132 (64.3) | 15,591 (65.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Pre-TIMI flow, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| 0/1 | 5,799 (71.1) | 10,540 (66.7) | 16,339 (68.2) | |

| 2/3 | 2,352 (28.9) | 5,258 (33.3) | 7,610 (31.8) | |

| Left ventricular dysfunction, n (%) | 3,488 (50.7) | 6,366 (48.5) | 9,854 (49.2) | 0.08 |

| Collateral circulation, n (%) | 1,361 (16.7) | 2,221 (14.1) | 3,582 (15.0) | 0.0004 |

LMCA: left main coronary artery; LAD: left anterior descending artery; RCA: right coronary artery; LCx: left circumflex artery; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Characteristics of the procedures.

| Smoking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Yes (n = 6,880 patients/ 6,953 procedures/ 8,171 stents) | No (n = 13,133 patients/ 13,357 procedures / 15,357 stents | Total (n = 20,013 patients/ 20,310 procedures / 23,528 stents) | p-value |

| PCI, n (%) | 0.0003 | |||

| Primary | 6,431 (92.5) | 12,532 (93.8) | 18,963 (93.4) | |

| Rescue | 522 (7.5) | 825 (6.2) | 1,347 (6.6) | |

| Treated vessels per patient | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1,2 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.60 |

| Stent use, n (%) | 6,459 (93.9) | 12,071 (91.9) | 18,530 (92.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Stent/patient ratio | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 0.45 |

| Drug-eluting stents, n (%) | 320 (3.9) | 1,196 (7.8) | 1,516 (6.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Stent diameter, mm | 3.12 ± 0.47 | 3.07 ± 0.47 | 3.09 ± 0.47 | < 0.0001 |

| Stent length, mm | 20.4 ± 6.5 | 20.6 ± 6.8 | 20.5 ± 6.7 | 0.16 |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors, n (%) | 1,311 (18.9) | 2,084 (15.6) | 3,395 (16.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Thrombus aspiration, n (%) | 477 (5.8) | 644 (4.2) | 1,121 (4.8) | < 0.0001 |

| TIMI flow post, n (%) | 0.07 | |||

| 0/1 | 362 (4.4) | 605 (3.9) | 967 (4.1) | |

| 2/3 | 7,803 (95.6) | 14,741 (96.1) | 22,544 (95.9) | |

| Diameter stenosis, (%) | ||||

| Pre | 96.4 ± 8.1 | 96.1 ± 8.8 | 96.2 ± 8.6 | 0.007 |

| Post | 3.7 ± 9.9 | 4.2 ± 11.1 | 4 ± 10.7 | 0.0001 |

| Procedural success, n (%) | 6,547 (94.2) | 12,298 (92.1) | 18,845 (92.8) | < 0.0001 |

PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; GP: glycoprotein; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

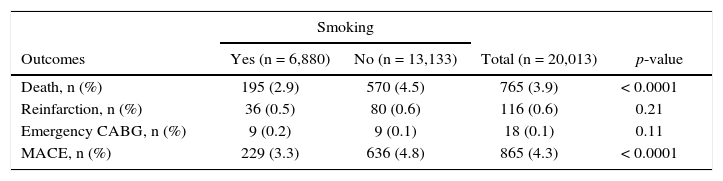

During the in-hospital phase, no difference was observed regarding the rates of reinfarction or emergency revascularization between smokers and non-smokers. Patients who were smokers had a lower in-hospital death rate (2.9% vs. 4.5%, p < 0.0001) and a lower rate of major adverse cardiac events (3.3% vs. 4.8%, p < 0.0001) (Table 4).

In-hospital outcomes.

| Smoking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Yes (n = 6,880) | No (n = 13,133) | Total (n = 20,013) | p-value |

| Death, n (%) | 195 (2.9) | 570 (4.5) | 765 (3.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Reinfarction, n (%) | 36 (0.5) | 80 (0.6) | 116 (0.6) | 0.21 |

| Emergency CABG, n (%) | 9 (0.2) | 9 (0.1) | 18 (0.1) | 0.11 |

| MACE, n (%) | 229 (3.3) | 636 (4.8) | 865 (4.3) | < 0.0001 |

CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; MACE: major adverse cardiac events.

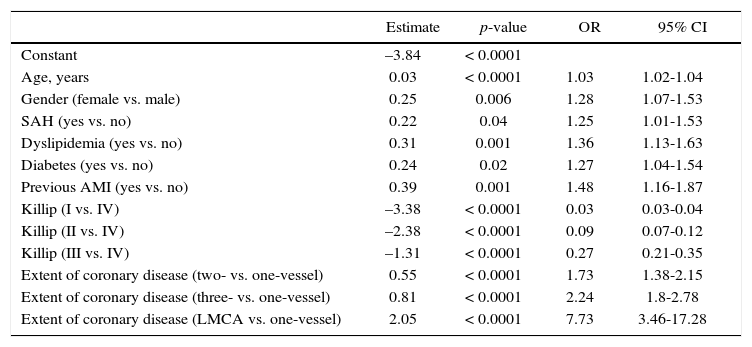

The factors that showed a significant association with death were female gender, presence of comorbidities (diabetes and previous history of AMI), and myocardial revascularization. Similarly, patients with Killip IV at presentation, three-vessel disease, ventricular dysfunction, and use of glycoprotein inhibitors presented an increased risk of mortality. The univariate analysis showed that non-smokers had a higher risk of death (odds ratio – OR = 1.59, 95% confidence interval – 95% CI: 1.35-1.87). However, the adjusted analysis showed that smoking was not a protective factor for mortality (OR = 1.13, 95% CI: 0.95-1.34, p = 0.16). The clinical characteristics that suggested a positive and statistically significant association with death were age, gender, systemic arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, history of AMI, Killip classification, and extent of coronary disease (Table 5).

Multiple logistic regression.

| Estimate | p-value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | –3.84 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Age, years | 0.03 | < 0.0001 | 1.03 | 1.02-1.04 |

| Gender (female vs. male) | 0.25 | 0.006 | 1.28 | 1.07-1.53 |

| SAH (yes vs. no) | 0.22 | 0.04 | 1.25 | 1.01-1.53 |

| Dyslipidemia (yes vs. no) | 0.31 | 0.001 | 1.36 | 1.13-1.63 |

| Diabetes (yes vs. no) | 0.24 | 0.02 | 1.27 | 1.04-1.54 |

| Previous AMI (yes vs. no) | 0.39 | 0.001 | 1.48 | 1.16-1.87 |

| Killip (I vs. IV) | –3.38 | < 0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.03-0.04 |

| Killip (II vs. IV) | –2.38 | < 0.0001 | 0.09 | 0.07-0.12 |

| Killip (III vs. IV) | –1.31 | < 0.0001 | 0.27 | 0.21-0.35 |

| Extent of coronary disease (two- vs. one-vessel) | 0.55 | < 0.0001 | 1.73 | 1.38-2.15 |

| Extent of coronary disease (three- vs. one-vessel) | 0.81 | < 0.0001 | 2.24 | 1.8-2.78 |

| Extent of coronary disease (LMCA vs. one-vessel) | 2.05 | < 0.0001 | 7.73 | 3.46-17.28 |

SAH: systemic arterial hypertension; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; LMCA: left main coronary artery; OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

The present study is one of the largest analyses performed in Brazilian patients with STEMI, both smokers and non-smokers, submitted to primary or rescue PCI, encompassing 20,013 patients. The significant size of the cohort makes this a robust observational study, and the data shown herein come from the updated clinical practice of the last 10 years in Brazil. Although clinical outcomes were favorable to smokers, the multivariate analysis did not demonstrate a protective effect of smoking in this group of patients.

Approximately one-third of the patients in this sample were smokers. This agrees with previous studies, which stated that 25 to 50% of patients with coronary artery disease were self-reported smokers at the time of the PCI.7–10 A publication of the CENIC registry of patients treated by PCI between 2006 and 2012 showed a higher frequency of smokers when compared to the present, more contemporary series (38% vs. 34.4%).6 Moreover, considering that the prevalence of smokers in the Brazilian population is approximately 17%, the prevalence of smoking in the present study can be justified by the fact that smoking is a risk factor for coronary artery disease.11

The mean age of smokers in this study was 57.7 years, that is, approximately 5 years younger than non-smokers. The present data is in agreement with the literature, which shows that patients with a history of smoking are younger, more frequently males, and have fewer cardiovascular risk factors.7–9

The angiographic characteristics of smokers were different from those of non-smokers. In this study, smokers had a higher frequency of one-vessel disease and greater complexity of the treated lesion, with a higher prevalence of thrombi, long or bifurcation lesions, and TIMI flow 0/1. The pathogenesis of coronary occlusion in smokers is related to a greater thrombotic rather than atherosclerotic burden, due to the impact of smoking on platelet activation and aggregation, coronary vasoconstriction, and fibrinogen increase.12 Although single-vessel disease is associated with less atherosclerotic involvement, it was more frequent in the cohort of smokers and may be associated with the younger age profile of this group,13 with a direct impact on the frequency of treated vessels and stents per patient.14

Although younger, smokers had more visible collateral circulation than non-smokers. This characteristic was not consistent with previous studies, which showed that older patients had a greater presence of collateral circulation when compared to their younger peers.15

Similarly to previous CENIC results,7 high clinical success rates (94.2%) and low rates of emergency myocardial revascularization or in-hospital death (2.9%) were observed among smokers. Although a paradoxical effect of smoking was observed, the multivariate analysis did not confirm this association with lower in-hospital mortality. Furthermore, studies evaluating long-term mortality have associated unfavorable outcomes to smokers.16 Steelle et al. reported a mortality rate at 1 year of 8.3% in a cohort of smokers (7%), ex-smokers (9.2%), and non-smokers (6.4%).17 Another study, with 6,676 patients with AMI selected for the TRACE (TRAndolapril Cardiac Evaluation) study, found that long-term mortality was lower among smokers than ex- or non-smokers. However, the adjusted analysis provided no evidence to support the existence of a smoking paradox in this population.22 The OPTIMAAL (Optimal Trial In Myocardial Infarction with the Angiotensin Antagonist Losartan) study analyzed patients with AMI and evidence of heart failure randomized to captopril vs. losartan. The unadjusted mortality rate among smokers was 17% lower than among non-smokers, but this reduced risk was eliminated after adjusting for age and other initial differences.15 Finally, the GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) study investigated 19,325 hospitalized patients diagnosed with ACS, and indicated that the hospital mortality rate in smokers was half of that in patients who never smoked (3.3% vs. 6.9%). However, there was no significant difference in the adjusted estimated relative risk for smokers when compared with those who never smoked. These results were consistent in all three subgroups of the studied ACS population (STEMI, non-ST elevation infarction, or unstable angina).18 These studies have shown robust evidence challenging the protective effect of smoking and demonstrating that such paradoxical effect does not exist.8,18,19 In the systematic review by Aune et al., the phenomenon of the paradoxical effect occurred predominantly in populations treated with fibrinolysis. Even after analyzing 17 studies, the authors concluded that smoking did not reduce the risk of negative outcomes, and the recommendation is to emphasize the benefits of smoking cessation against the potential beneficial effects of the paradoxical effect.16 Similarly, the present results cannot be associated with a protective effect of smoking, since the negative outcomes were considered multifactorial, and the association of mortality with smoking was not confirmed by the multivariate analysis.

LimitationsAmong the limitations, the authors highlight the retrospective design of the study, subject to possible confounders not included in the analyses. Furthermore, the assessment of smoking status was carried out in each institution, not being standardized.

ConclusionsAlthough the clinical outcomes associated with primary or rescue percutaneous coronary intervention were more favorable to smokers, the multivariate analysis did not demonstrate a protective effect of smoking in this group of patients. These results may be associated to differences in clinical, angiographic, and procedural characteristics.

Sources of fundingThe Brazilian Society of Hemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology provided financial support.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

To the Brazilian Society of Hemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology and to all the physicians and institutions involved in the CENIC registry.

Peer review under the responsibility of Sociedade Brasileira de Hemodinâmica e Cardiologia Intervencionista.