There are few available reports in the literature assessing in-hospital outcomes of diabetic patients currently undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). This article aimed to assess the acute post-PCI outcomes of a large series of diabetic and non-diabetic patients treated consecutively.

MethodsFrom August 2006 to February 2012, 6,011 patients were submitted to PCI and included in the registry of the Hospital Bandeirantes. The techniques and devices for the procedure were chosen by the surgeons. Clinical outcomes were registered at the time of hospital discharge.

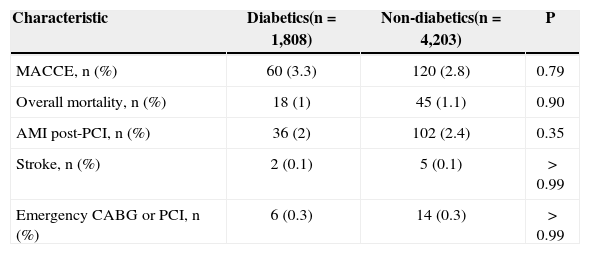

ResultsDiabetic patients were older and more frequently females, with a higher prevalence of comorbidities and risk factors for coronary artery disease, except for smoking. However, most of the characteristics related to lesion complexity did not differ between groups. In diabetics, the number of treated vessels (1.6±0.8 vs. 1.4±0.7; P < 0.01) was higher, and the use of smaller stents (2.9±0.5mm vs. 3±0.5mm; P < 0.01) was more frequent. A procedural success rate of 95.5% was achieved in both groups. In-hospital outcomes did not differ in the incidence of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (3.3% vs. 2.8%; P=0.79), death (1% vs. 1.1%; P=0.90), acute myocardial infarction (2% vs. 2.4%; P=0.35), stroke (0.1% in both groups), and emergency revascularisation (0.3% in both groups). Arterial hypertension was the variable that best explained the occurrence of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events [odds ratio (OR): 2.68, 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 1.13–6.38; P=0.026).

ConclusionsDiabetes mellitus adds more clinical complexity to PCI but has no significant impact on in-hospital outcomes.

Resultados Hospitalares da IntervençãoCoronária Percutânea em Diabéticos

IntroduçãoPoucas publicações estão disponíveis na literatura avaliando a evolução hospitalar de pacientes diabéticos submetidos a intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP) na era contemporânea. Nosso objetivo foi avaliar os resultados agudos pós-ICP de uma grande série de pacientes diabéticos e não diabéticos, tratados consecutivamente.

MétodosNo período de agosto de 2006 a fevereiro de 2012, 6.011 pacientes foram submetidos a ICP e incluídos no Registro do Hospital Bandeirantes. A técnica e a escolha do material durante o procedimento ficaram a cargo dos operadores. Os desfechos clínicos foram registrados no momento da alta hospitalar.

ResultadosOs diabéticos mostraram ser mais idosos, mais frequentemente do sexo feminino, com maior prevalência de comorbidades e fatores de risco para doença arterial coronária, à exceção do tabagismo. A maioria das características de complexidade das lesões, no entanto, não diferiu entre os grupos. Nos diabéticos, o número de vasos tratados (1,6±0,8 vs. 1,4±0,7; P < 0,01) foi maior e o uso de stents de menor calibre (2,9±0,5mm vs. 3±0,5mm; P < 0,01) foi mais frequente. Taxa de sucesso do procedimento de 95,5% foi alcançada nos dois grupos. Os desfechos hospitalares não mostraram diferenças quanto à incidência de eventos cardíacos e cerebrovasculares adversos maiores (3,3% vs. 2,8%; P=0,79), óbito (1% vs. 1,1%; P=0,90), infarto agudo do miocárdio (2% vs. 2,4%; P=0,35), acidente vascular cerebral (0,1% em ambos os grupos), e revascularização de emergência (0,3% em ambos os grupos). Hipertensão arterial foi a variável que melhor explicou a ocorrência de eventos cardíacos e cerebrovasculares adversos maiores [odds ratio (OR) 2,68, intervalo de confiança de 95% (IC 95%) 1,136,38; P=0,026).

ConclusõesO diabetes agrega maior complexidade clínica à ICP, sem modificar, entretanto, os desfechos clínicos hospitalares.

The number of diabetic individuals is increasing due to population growth and aging, greater urbanisation, and higher prevalence of obesity and sedentary lifestyle. Type 2 diabetes has become a global epidemic, with an estimated 173 million diabetic individuals in 2002. This number is projected to reach 300 million in 2030.1

Diabetes is a known risk factor for the development of atherosclerosis, which is a major cause of mortality in this group of patients.2 Patients with diabetes mellitus are at increased risk of cardiovascular events and death compared with those without the disease and account for approximately one-third of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the United States.3

Percutaneous and surgical myocardial revascularisation therapies are important tools in the treatment of coronary artery disease, which impacts quality of life and survival. Results among diabetics, however, are less pronounced, with a greater occurrence of new revascularisations in late follow-up, especially in patients with multivessel disease.4 The complexity of coronary lesions, the rapid progression of atherosclerotic disease, and the higher rates of restenosis, even when using drug-eluting stents, are some of the reasons for these results.

However, few studies are currently available regarding the in-hospital results of PCI in diabetic patients. This article aimed to evaluate the acute post-PCI outcomes of a large series of consecutively treated diabetic and non-diabetic patients.

METHODSPatientsFrom August, 2006 to February, 2012, 6,011 consecutive patients underwent PCI and were included in the Hospital Bandeirantes Registry. Data were collected prospectively and stored in a computerised database.

Clinical outcomes were registered at the time of hospital discharge.

PCIAlmost all interventions were conducted by femoral access, and radial access was used as an alternative in a few cases. The materials and technique used during the procedure and the need for glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were chosen by the surgeons. Unfractionated heparin was used at the beginning of the procedure at a dose of 70 U/kg to 100 U/kg, except in patients who were already using low molecular-weight heparin.

All patients received antiplatelet therapy in combination with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) with a loading dose of 300mg and a maintenance dose of 100mg/day to 200mg/day and a clopidogrel loading dose of 300mg to 600mg with a maintenance dose of 75mg/day. The femoral sheaths were removed four hours after the start of heparinisation. The radial sheaths were removed immediately after the procedure.

Angiographic analysis and definitionsThe analyses were performed in at least two orthogonal projections by experienced technicians using digital quantitative angiography. This study used the same angiographic criteria listed in the database of the National Centre of Cardiovascular Interventions (Central Nacional de Intervenções Cardiovasculares – CENIC) of the Brazilian Society of Interventional Cardiology. The type of lesion was classified according to the criteria of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA).5 The thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) classification was used to determine the pre- and post-procedural coronary flow.6 Procedural success was defined as achievement of angiographic success (residual stenosis < 30% with TIMI flow 3) and absence of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) comprising death, periprocedural myocardial infarction, stroke, and emergency coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.7

Deaths from any cause were recorded, and cardiac mortality was defined as mortality resulting from cardiogenic shock, heart failure, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), cardiac rupture, arrhythmia, or sudden death during the hospitalisation period. Peri-PCI infarction was defined by the reappearance of angina symptoms with electrocardiographic alterations (new ST-segment elevation or new Q waves) and/or angiographic evidence of target vessel occlusion. Emergency CABG was considered when performed immediately after the PCI.

Statistical analysisThe data, stored in an Oracle database, were Oracle database were plotted in Excel spreadsheets and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), release 15.0. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean±standard deviation, and categorical variables were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. Associations between continuous variables were evaluated using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) model. Associations between categorical variables were evaluated by chi-aquared or Fisher’s exact tests or likelihood ratios when appropriate. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05. Simple and multiple logistic regression models were applied to identify MACCE predictors.

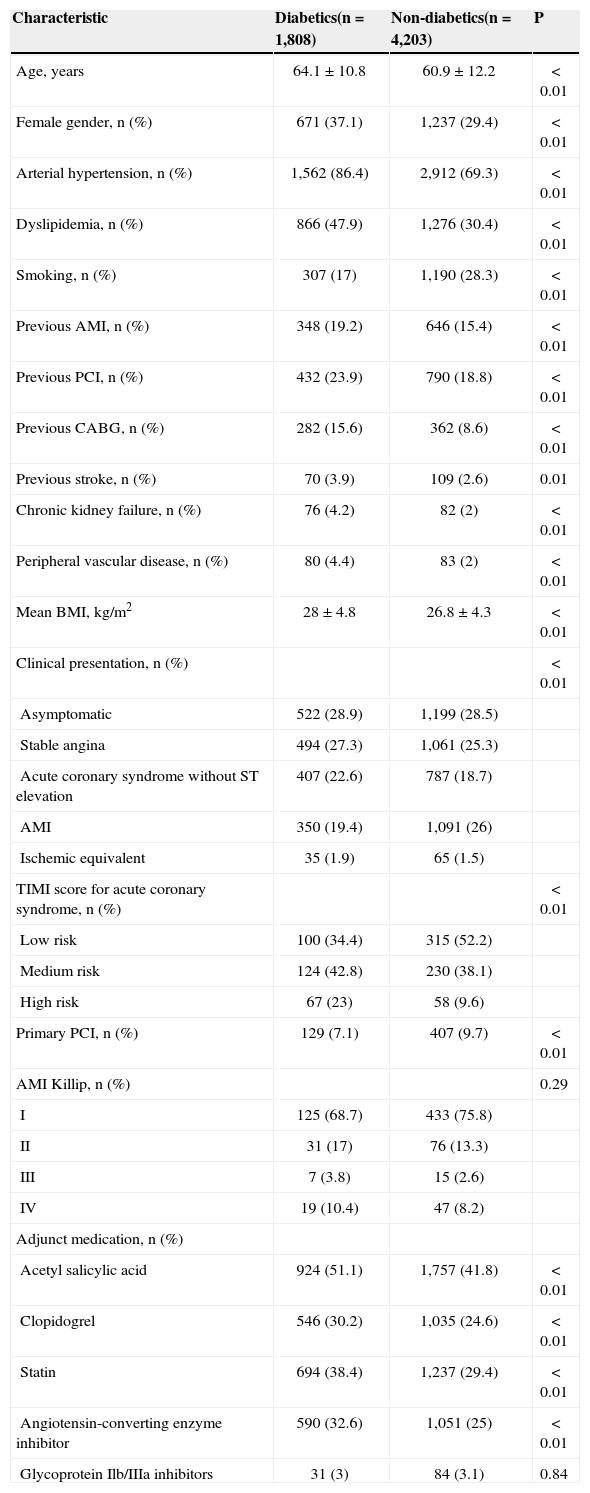

RESULTSThe clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The diabetic group was 3 years older (64.1years vs. 60.9years; P < 0.01), with a higher proportion of women (37.1% vs. 29.4%; P < 0.01) and a higher body mass index (28±4.8kg/m2 vs. 26.8±4.3kg/m2; P < 0.01) compared with non-diabetics. Moreover, diabetics had a predominance of hypertension (86.4% vs. 69.3%; P < 0.01), dyslipidemia (47.9% vs. 30.4%; P < 0.01), chronic kidney failure (4.2% vs. 2%; P < 0.01), peripheral vascular disease (4.4% vs. 2%; P < 0.01), previous AMI (19.2% vs. 15.4%; P < 0.01), stroke (3.9% vs. 2.6%; P < 0.01), CABG (15.6% vs. 8.6%; P < 0.01), and PCI (23.9% vs. 18.8%; P < 0.01). Smoking was the only coronary risk factor that was predominant among non-diabetics (17% vs. 28.3%; P < 0.01). The clinical presentation was different between groups (P < 0.01); acute coronary syndrome without ST segment elevation was more frequent in the diabetic group (22.6% vs. 18.7%) and AMI with ST segment elevation was more frequent in the non-diabetic group (19.4% vs. 26%).

Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristic | Diabetics(n=1,808) | Non-diabetics(n=4,203) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64.1±10.8 | 60.9±12.2 | < 0.01 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 671 (37.1) | 1,237 (29.4) | < 0.01 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 1,562 (86.4) | 2,912 (69.3) | < 0.01 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 866 (47.9) | 1,276 (30.4) | < 0.01 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 307 (17) | 1,190 (28.3) | < 0.01 |

| Previous AMI, n (%) | 348 (19.2) | 646 (15.4) | < 0.01 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 432 (23.9) | 790 (18.8) | < 0.01 |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 282 (15.6) | 362 (8.6) | < 0.01 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 70 (3.9) | 109 (2.6) | 0.01 |

| Chronic kidney failure, n (%) | 76 (4.2) | 82 (2) | < 0.01 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 80 (4.4) | 83 (2) | < 0.01 |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 | 28±4.8 | 26.8±4.3 | < 0.01 |

| Clinical presentation, n (%) | < 0.01 | ||

| Asymptomatic | 522 (28.9) | 1,199 (28.5) | |

| Stable angina | 494 (27.3) | 1,061 (25.3) | |

| Acute coronary syndrome without ST elevation | 407 (22.6) | 787 (18.7) | |

| AMI | 350 (19.4) | 1,091 (26) | |

| Ischemic equivalent | 35 (1.9) | 65 (1.5) | |

| TIMI score for acute coronary syndrome, n (%) | < 0.01 | ||

| Low risk | 100 (34.4) | 315 (52.2) | |

| Medium risk | 124 (42.8) | 230 (38.1) | |

| High risk | 67 (23) | 58 (9.6) | |

| Primary PCI, n (%) | 129 (7.1) | 407 (9.7) | < 0.01 |

| AMI Killip, n (%) | 0.29 | ||

| I | 125 (68.7) | 433 (75.8) | |

| II | 31 (17) | 76 (13.3) | |

| III | 7 (3.8) | 15 (2.6) | |

| IV | 19 (10.4) | 47 (8.2) | |

| Adjunct medication, n (%) | |||

| Acetyl salicylic acid | 924 (51.1) | 1,757 (41.8) | < 0.01 |

| Clopidogrel | 546 (30.2) | 1,035 (24.6) | < 0.01 |

| Statin | 694 (38.4) | 1,237 (29.4) | < 0.01 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor | 590 (32.6) | 1,051 (25) | < 0.01 |

| Glycoprotein Ilb/IIIa inhibitors | 31 (3) | 84 (3.1) | 0.84 |

AMI=acute myocardial infarction; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; BMI=body mass index; CABG=coronary artery bypass graft; TIMI=thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Regarding the pre-intervention cardiovascular medication, diabetics more frequently used acetylsalicylic acid (51.1% vs. 41.8%; P < 0.01), clopidogrel (30.2% vs. 24.6%; P < 0.01), statins (38.4% vs. 29.4%; P < 0.01), and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (32.6% vs. 25%; P < 0.01). The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors during the procedure did not differ between groups.

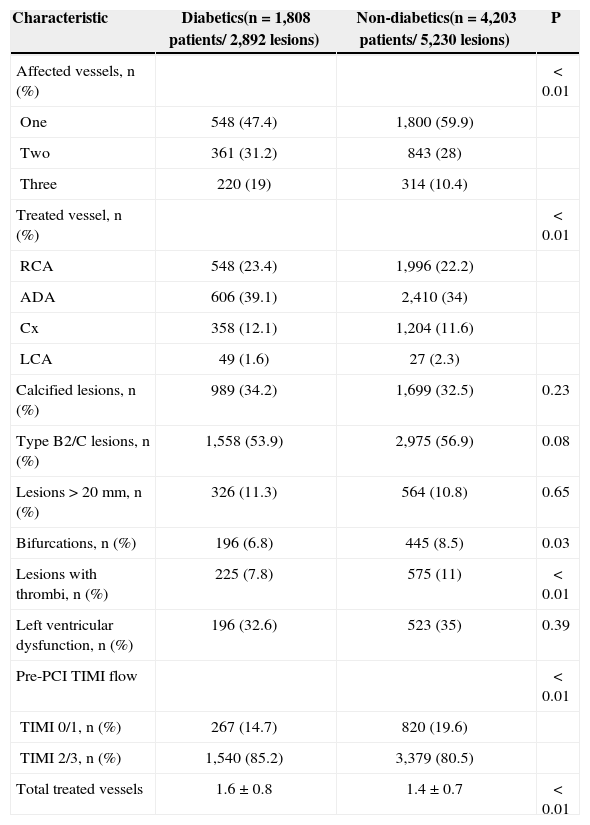

Table 2 shows the angiographic characteristics. There was a predominance of multivessel disease, with lesions in two or three vessels in diabetics (31.2% vs. 28% and 19% vs. 10.4%, respectively; P < 0.01). The left anterior descending artery was the most frequently approached vessel in both groups (39.1% vs. 34%; P < 0.01). The interventions were mostly performed in B2/C lesions (53.9% vs. 56.9%; P=0.08), and most of the characteristics of lesion complexity did not differ between the groups. However, the presence of thrombi in the treated lesion (7.8% vs. 11%; P < 0.01) and the TIMI flow 0/1 in the vessel to be treated (14.7% vs. 19.6%; P < 0.01) was lower in the diabetic group.

Angiographic Characteristics

| Characteristic | Diabetics(n=1,808 patients/ 2,892 lesions) | Non-diabetics(n=4,203 patients/ 5,230 lesions) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affected vessels, n (%) | < 0.01 | ||

| One | 548 (47.4) | 1,800 (59.9) | |

| Two | 361 (31.2) | 843 (28) | |

| Three | 220 (19) | 314 (10.4) | |

| Treated vessel, n (%) | < 0.01 | ||

| RCA | 548 (23.4) | 1,996 (22.2) | |

| ADA | 606 (39.1) | 2,410 (34) | |

| Cx | 358 (12.1) | 1,204 (11.6) | |

| LCA | 49 (1.6) | 27 (2.3) | |

| Calcified lesions, n (%) | 989 (34.2) | 1,699 (32.5) | 0.23 |

| Type B2/C lesions, n (%) | 1,558 (53.9) | 2,975 (56.9) | 0.08 |

| Lesions>20mm, n (%) | 326 (11.3) | 564 (10.8) | 0.65 |

| Bifurcations, n (%) | 196 (6.8) | 445 (8.5) | 0.03 |

| Lesions with thrombi, n (%) | 225 (7.8) | 575 (11) | < 0.01 |

| Left ventricular dysfunction, n (%) | 196 (32.6) | 523 (35) | 0.39 |

| Pre-PCI TIMI flow | < 0.01 | ||

| TIMI 0/1, n (%) | 267 (14.7) | 820 (19.6) | |

| TIMI 2/3, n (%) | 1,540 (85.2) | 3,379 (80.5) | |

| Total treated vessels | 1.6±0.8 | 1.4±0.7 | < 0.01 |

RCA=right coronary artery; Cx=circumflex artery; ADA=anterior descending artery; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; TIMI=thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

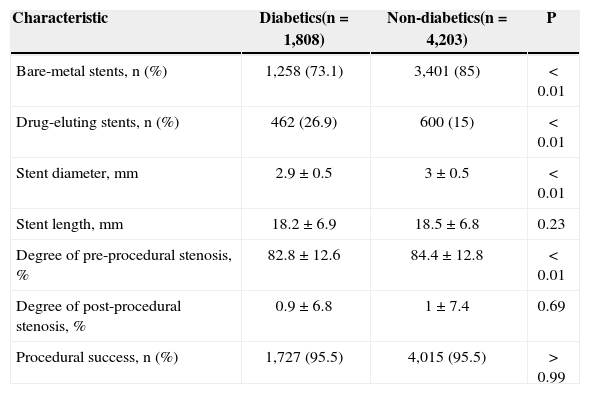

The diabetic group showed a higher number of treated vessels and greater use of drug-eluting stents (26.9% vs. 15%; P < 0.01) (Table 3). The angiographic quantification of obstructions before the procedure showed a higher percentage of luminal obstruction by plaque among non-diabetics (82.8±12.6mm vs. 84.4±12.8mm; P < 0.01), with no differences between the groups regarding the quantification of obstruction after the procedure. The stents implanted in the diabetic group had a smaller diameter (2.9±0.5mm vs. 3±0.5mm; P < 0.01), with no difference regarding length compared with non-diabetics (18.2±6.9mm vs. 18.5±6.8mm; P=0.23). A high rate (95.5%) of procedural success was achieved in both groups.

Procedural Characteristics

| Characteristic | Diabetics(n=1,808) | Non-diabetics(n=4,203) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bare-metal stents, n (%) | 1,258 (73.1) | 3,401 (85) | < 0.01 |

| Drug-eluting stents, n (%) | 462 (26.9) | 600 (15) | < 0.01 |

| Stent diameter, mm | 2.9±0.5 | 3±0.5 | < 0.01 |

| Stent length, mm | 18.2±6.9 | 18.5±6.8 | 0.23 |

| Degree of pre-procedural stenosis, % | 82.8±12.6 | 84.4±12.8 | < 0.01 |

| Degree of post-procedural stenosis, % | 0.9±6.8 | 1±7.4 | 0.69 |

| Procedural success, n (%) | 1,727 (95.5) | 4,015 (95.5) | > 0.99 |

The in-hospital outcomes (Table 4) of PCI showed no differences between the groups in the incidence of MACCE (3.3% vs. 2.8%; P=0.79) or occurrence of in-hospital death (1% vs. 1.1%; P=0.90), AMI (2% vs. 2.4%; P=0.35), stroke (0.1% in both groups), and new emergency intervention (PCI or CABG) (0.3% in both groups).

In-hospital Clinical Outcomes

| Characteristic | Diabetics(n=1,808) | Non-diabetics(n=4,203) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACCE, n (%) | 60 (3.3) | 120 (2.8) | 0.79 |

| Overall mortality, n (%) | 18 (1) | 45 (1.1) | 0.90 |

| AMI post-PCI, n (%) | 36 (2) | 102 (2.4) | 0.35 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 2 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) | > 0.99 |

| Emergency CABG or PCI, n (%) | 6 (0.3) | 14 (0.3) | > 0.99 |

Emergency CABG or PCI, n (%) 6 (0.3) 14 (0.3) > 0.99 MACCE=major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; AMI=acute myocardial infarction; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG=coronary artery bypass graft.

Age, hypertension, previous stroke, use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, acute coronary syndrome, extension of the obstructive coronary disease, lesions with thrombus, pre-intervention TIMI flow, number of treated vessels, and long lesions and type B2/C lesions had a significant association with the occurrence of events in the univariate analysis; only hypertension [odds ratio (OR): 2.68, 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 1.13–6.38; P=0.026)] was the variable that best explained the presence of MACCE in the studied population.

DISCUSSIONThe presence of diabetes mellitus in patients with atherosclerotic disease is a marker of poor prognosis when they are submitted to PCI, with a higher incidence of complications and restenosis.8–10 It is believed that this is due to endothelial and metabolic alterations, which lead to a greater chance of atherosclerotic plaque rupture and thrombus formation and increased exacerbation of intimal hyperplasia.10–12 In the present study, the impact of diabetes mellitus on in-hospital outcomes was evaluated in a large cohort of patients currently undergoing PCI.

According to the clinical characteristics of patients, most cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities were more common in diabetics, which would indicate a poor clinical outcome in this group.8–12 However, the present findings demonstrated no influence of diabetes on clinically adverse events at the hospitalisation phase, despite the greater clinical complexity of patients. The angiographic profile of diabetic patients, however, showed no difference for most analysed variables compared with non-diabetics, which suggests that the appropriate choice of cases attenuated the higher number of in-hospital events expected for that group.

The present findings are consistent with previous studies, such as that by Stein et al.,13 in which elective angioplasties of 1,133 diabetics and 9,300 non-diabetic patients between 1980 and 1990 were analysed. Similarly, the authors observed that diabetics were older, were more often females, and had a history of previous AMI, arterial hypertension, and multivessel involvement. In this study, there was no difference regarding the in-hospital clinical outcomes between diabetics and non-diabetics.

In a recent study, Li et al.14 evaluated 1,294 patients and found a higher incidence of acute/subacute in-stent thrombosis in the diabetic group. However, as in the present study, the presence of diabetes mellitus was not an independent predictor of cardiovascular events during hospitalisation.

In contrast, according to the database of the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR), which covered procedures performed from 2004 to 2007, the rate of overall in-hospital mortality was 1.27%, and the presence of diabetes mellitus was an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality after PCI.15–17

The observation of a poorer prognosis in diabetic patients is more consistent in the late outcome after PCI, which may be explained by higher rates of restenosis and disease progression in this group of patients.1,8–10 In Brazil, the Drug-Eluting Stent in the Real World (DESIRE registry),18 which assessed the predictors of target lesion revascularisation in a long-term clinical follow-up, demonstrated that diabetes mellitus predisposes individuals to a greater need for new procedures. A subanalysis of the same registry, which evaluated the late outcome after PCI with drug-eluting stents in diabetic patients, showed that, when analysed in combination, major cardiac events occurred more frequently in the diabetic group, although still at very low rates.19

Data from the BARI Registry, the Duke International Registry, and the Northern New England Study Group suggest that careful selection of diabetic patients for PCI can minimise the differences in results in relation to the modality of surgical myocardial revascularisation, and the use of drug-eluting stents is thus imperative in this population.9,20 The study by Tanajura et al.,4 which assessed the influence of using drug-eluting stents in the selection of diabetic patients treated with PCI, observed a change in the profile of these patients, demonstrating that the increased availability of drug-eluting stents expands the indications for more complex cases and allows for a more complete myocardial revascularisation. In the present analysis, diabetic patients received more drug-eluting stents than non-diabetics in percentage terms, but this rate was not higher because the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde – SUS) does not provide this technology to its users.

Study limitationsLimitations of this study include the retrospective analysis of data, its performance in a single centre, and the absence of late follow-up.

CONCLUSIONSDiabetes mellitus adds more clinical complexity to patients treated by PCI, but does not modify in-hospital clinical outcomes.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.