The use of statins prior to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has reduced cardiac events in both short and long-term follow-up. This study assessed the impact of prior statin use on in-hospital PCI outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

MethodsRetrospective analysis of a multicenter registry of 6,288 consecutive patients undergoing PCI. Of these, 35% had ACS and were evaluated according to statin use (Group 1, n=1,203) or no use (Group 2, n=999).

ResultsGroup 1 showed higher prevalence of dyslipidemia, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), previous coronary artery bypass graft, chronic renal failure, multivessel involvement, bifurcation lesions, and use of drug-eluting stents. Group 2 showed more primary and rescue PCIs, Killip functional class III/IV, B2/C lesions, thrombi, total occlusions, pre-procedural TIMI 0/1 flow, presence of collateral circulation, and use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors and aspiration catheters. PCI success was higher in Group 1 (95.1% vs. 92.5%; p=0.01), and the occurrence of major adverse cerebrovascular and cardiac events (MACCE) (3.7% vs. 5.7%) was more frequent in Group 2. Although the non-use of statins showed an association with MACCE in the univariate analysis, independent predictors of in-hospital MACCE were limited to AMI in Killip III/IV and prior coronary artery bypass graft.

ConclusionsACS patients undergoing PCI who previously used statins had better in-hospital clinical outcomes; however, statin use was not an independent predictor of MACCE.

O uso de estatinas previamente à intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP) tem reduzido eventos cardíacos na evolução de curto e longo prazos. Avaliamos o impacto do uso prévio de estatinas nos resultados hospitalares da ICP em pacientes com síndrome coronariana aguda (SCA).

MétodosAnálise retrospectiva de registro multicêntrico com 6.288 pacientes submetidos consecutivamente à ICP. Destes, 35% tinham SCA e foram avaliados de acordo com a utilização (Grupo 1, n=1.203) ou não (Grupo 2, n=999) de estatinas.

ResultadosO Grupo 1 mostrou maior prevalência de dislipidemia, infarto agudo do miocárdio (IAM) prévio, procedimentos de revascularização prévios, insuficiência renal crônica, acometimento multiarterial, lesões em bifurcação uso de stents farmacológicos. O Grupo 2 mostrou maior número de ICPs primária e de resgate, classe funcional Killip III/IV, lesões tipo B2/C, trombos, oclusões totais, fluxo TIMI pré 0/1, presença de circulação colateral, uso de inibidores da glicoproteína IIb/IIIa e de cateteres de aspiração. O sucesso da ICP foi maior no Grupo 1 (95,1% vs. 92,5%; p=0,01), e a ocorrência de eventos cardíacos e cerebrovasculares adversos maiores (ECCAM) (3,7% vs. 5,7%; p=0,04) foi mais frequente no Grupo 2. Apesar da não utilização de estatina ter apresentado associação com ECCAM na análise univariada, foram preditores independentes de ECCAM hospitalares apenas o IAM em Killip III/IV e a cirurgia de revascularização prévia.

ConclusõesPacientes com SCA submetidos à ICP e que estavam em uso prévio de estatinas apresentaram melhores resultados clínicos hospitalares, mas a utilização desses fármacos não foi preditora independente de ECCAM.

With the current technological advances, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has become the most commonly used therapeutic approach in the treatment of coronary artery disease (CAD). Although it restores myocardial flow, PCI carries a potential risk of myocardial damage, which is associated with increased morbidity and mortality due to late cardiac events.1–3 Many therapeutic strategies have been proposed to limit the occurrence and extent of periprocedural myocardial damage; however, myocardial injury still remains the most common complication of PCI.4–6 Therefore, understanding the mechanisms and finding adjunctive therapies to improve myocardial protection remain a challenge in modern Cardiology.

It has been increasingly demonstrated that statins have pleiotropic actions with beneficial effect on the cardiovascular system, which go far beyond simply the control of cholesterol level. These effects include improved endothelial function by increasing the levels and bioactivity of nitric oxide, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, and plaque stabilization.7,8

Based on these findings, it has been hypothesized that the use of statins may be associated with decreased rates of periprocedural acute myocardial infarction (AMI) by reducing the release of myocardial necrosis markers during the PCI through their pleiotropic effects on microcirculation. Several randomized studies have demonstrated the reduction in periprocedural AMI with high-dose statin use before PCI, and some have documented a reduction in major adverse cardiac events.9–13 Coronary flow improvement and mortality reduction have also been reported in patients that were chronic statin users and were submitted to primary PCI.14–17 However, in Brazil, there are no registries with a large number of patients evaluating whether the previous use of statin has an impact on major adverse cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events (MACCE) in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) submitted to PCI.

In this retrospective observational study, the authors aimed to assess the impact of the prior use of statins on in-hospital outcomes of PCI in patients with ACS.

MethodsPopulationFrom August 2006 to October 2012, 6,288 consecutive patients were submitted to PCI at the centers that comprise the Angiocardio Registry (Hospital Bandeirantes, Hospital Rede D’Or São Luiz Anália Franco, and Hospital Leforte in Sao Paulo; Hospital Vera Cruz in Campinas; and Hospital Regional do Vale do Paraíba in Taubaté – all in the State of São Paulo). Of these patients, 2,202 (35%) had a diagnosis of ACS and were assessed according to statin use (Group 1, n=1,203) or no use (Group 2, n=999).

Data were collected prospectively and stored in a computerized database available online in all centers participating in the registry.

The primary objective was to compare in-hospital MACCE rates between the two groups and assess the independent predictors of these events.

MedicationStatin use prior to hospitalization for ACS, regardless of the type, dose, and time of administration was considered previous statin use. All patients, irrespective of previous treatment or lack thereof, received simvastatin, rosuvastatin, or atorvastatin during hospitalization, according to the protocols of the institutions that comprise the Angiocardio Registry.

ProcedureMost interventions were performed through femoral approach, whereas the radial approach was used in the others. The technique and the choice of material during the procedure were at the discretion of the operators, as well as evaluating the need for the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Unfractionated heparin was used at the beginning of the procedure at a dose of 70 U/kg to 100 U/kg, except in patients who were already receiving low-molecular-weight heparin.

All patients received combined antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), at loading doses of 300mg and maintenance doses of 100 to 200mg/day, and clopidogrel, at loading doses of 300 or 600mg and maintenance doses of 75mg/day. The femoral sheaths were removed 4hours after the start of heparinization. Radial sheaths were removed immediately after the procedure.

The measurements of myocardial necrosis marker creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) activity considered for the analysis were performed immediately before the procedure and 12hours afterwards.

Angiographic analysis and definitionsAngiographic analyses were performed in at least two orthogonal projections by experienced operators, using digital quantitative angiography. This study used the same angiographic criteria found in the database of the National Center of Cardiovascular Interventions (Central Nacional de Intervenções Cardiovasculares [CENIC]) of the Brazilian Society of Interventional Cardiology (Sociedade Brasileira de Hemodinâmica e Cardiologia Intervencionista [SBHCI]). The lesion type was classified according to the criteria of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA).18 The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) classification was used to determine pre- and post-procedure coronary flow.19 Procedural success was defined as attaining angiographic success (residual stenosis<30% with TIMI 3 flow) and no MACCE, including death from any cause, periprocedural reinfarction, stroke, and emergency coronary artery bypass graft surgery.20

Periprocedural reinfarction was defined as the appearence of typical pain with electrocardiographic alterations (ST-segment elevation or pathological Q waves) and/or angiographic evidence of target-vessel occlusion. The results of post-PCI CK-MB were not included in this definition. Emergency coronary artery bypass graft surgery was defined as a procedure performed immediately after the PCI.

Statistical analysisThe data stored in an Oracle-based database were plotted on Excel spreadsheets and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Science version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation, and categorical variables as absolute number and percentage. The associations between continuous variables were assessed by Student's t-test, and nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney and Wilcoxon) were used for non-normal distribution (pre- and post-PCI CK-MB). Associations between categorical variables were evaluated by the Chi-squared test, Fisher's exact test, or the likelihood ratio test, as appropriate. Significance level was set at p<0.05. Simple and multiple logistic regression models were applied to identify MACCE predictors.

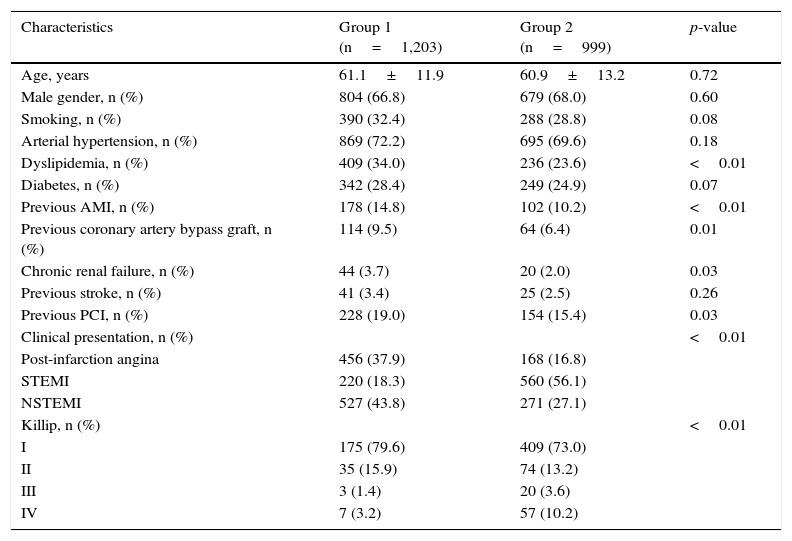

ResultsClinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Group 1 showed higher prevalence of dyslipidemia, previous AMI, previous coronary artery bypass graft, previous PCI, and chronic renal failure. Group 2 demonstrated a higher number of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and more advanced functional class (Killip III and IV).

Clinical characteristics.

| Characteristics | Group 1 (n=1,203) | Group 2 (n=999) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61.1±11.9 | 60.9±13.2 | 0.72 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 804 (66.8) | 679 (68.0) | 0.60 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 390 (32.4) | 288 (28.8) | 0.08 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 869 (72.2) | 695 (69.6) | 0.18 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 409 (34.0) | 236 (23.6) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 342 (28.4) | 249 (24.9) | 0.07 |

| Previous AMI, n (%) | 178 (14.8) | 102 (10.2) | <0.01 |

| Previous coronary artery bypass graft, n (%) | 114 (9.5) | 64 (6.4) | 0.01 |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 44 (3.7) | 20 (2.0) | 0.03 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 41 (3.4) | 25 (2.5) | 0.26 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 228 (19.0) | 154 (15.4) | 0.03 |

| Clinical presentation, n (%) | <0.01 | ||

| Post-infarction angina | 456 (37.9) | 168 (16.8) | |

| STEMI | 220 (18.3) | 560 (56.1) | |

| NSTEMI | 527 (43.8) | 271 (27.1) | |

| Killip, n (%) | <0.01 | ||

| I | 175 (79.6) | 409 (73.0) | |

| II | 35 (15.9) | 74 (13.2) | |

| III | 3 (1.4) | 20 (3.6) | |

| IV | 7 (3.2) | 57 (10.2) |

AMI: acute myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI: non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

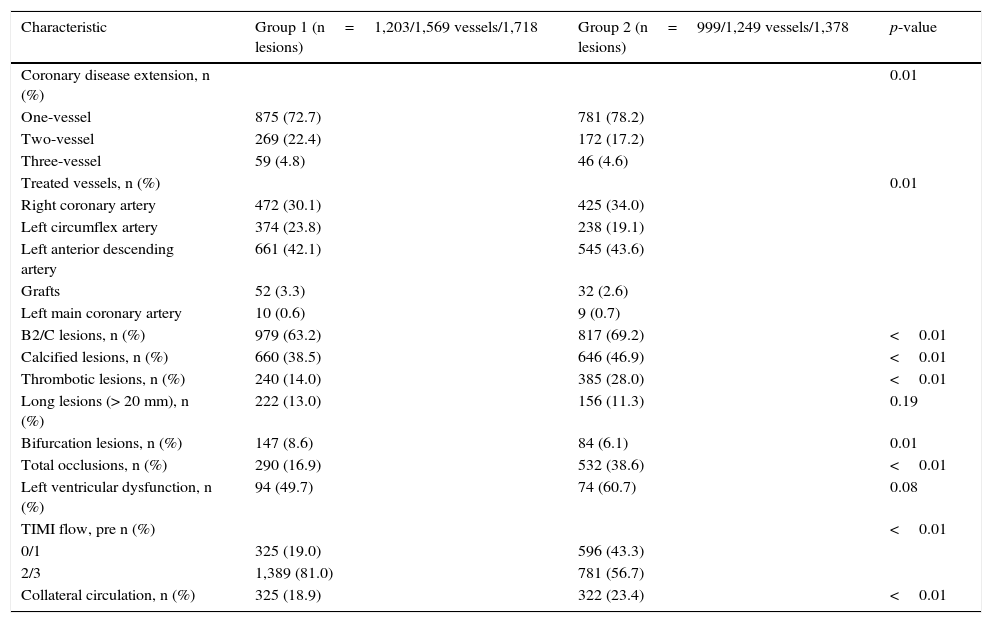

From the angiographic viewpoint (Table 2), patients who used statins had more multivessel involvement and bifurcation lesions. Group 2 patients had more type B2/C lesions, lesions with thrombi and calcified occlusions, higher prevalence of pre-PCI TIMI 0/1 flow, and the presence of collateral circulation.

Angiographic characteristics.

| Characteristic | Group 1 (n=1,203/1,569 vessels/1,718 lesions) | Group 2 (n=999/1,249 vessels/1,378 lesions) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary disease extension, n (%) | 0.01 | ||

| One-vessel | 875 (72.7) | 781 (78.2) | |

| Two-vessel | 269 (22.4) | 172 (17.2) | |

| Three-vessel | 59 (4.8) | 46 (4.6) | |

| Treated vessels, n (%) | 0.01 | ||

| Right coronary artery | 472 (30.1) | 425 (34.0) | |

| Left circumflex artery | 374 (23.8) | 238 (19.1) | |

| Left anterior descending artery | 661 (42.1) | 545 (43.6) | |

| Grafts | 52 (3.3) | 32 (2.6) | |

| Left main coronary artery | 10 (0.6) | 9 (0.7) | |

| B2/C lesions, n (%) | 979 (63.2) | 817 (69.2) | <0.01 |

| Calcified lesions, n (%) | 660 (38.5) | 646 (46.9) | <0.01 |

| Thrombotic lesions, n (%) | 240 (14.0) | 385 (28.0) | <0.01 |

| Long lesions (> 20 mm), n (%) | 222 (13.0) | 156 (11.3) | 0.19 |

| Bifurcation lesions, n (%) | 147 (8.6) | 84 (6.1) | 0.01 |

| Total occlusions, n (%) | 290 (16.9) | 532 (38.6) | <0.01 |

| Left ventricular dysfunction, n (%) | 94 (49.7) | 74 (60.7) | 0.08 |

| TIMI flow, pre n (%) | <0.01 | ||

| 0/1 | 325 (19.0) | 596 (43.3) | |

| 2/3 | 1,389 (81.0) | 781 (56.7) | |

| Collateral circulation, n (%) | 325 (18.9) | 322 (23.4) | <0.01 |

TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

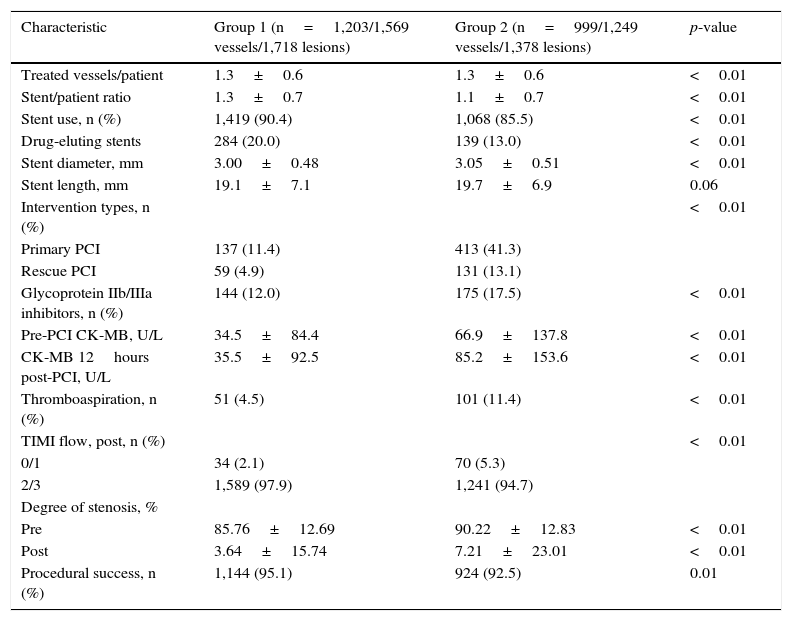

As for the procedural characteristics (Table 3), Group 1 used more drug-eluting stents with a higher stent/patient ratio, whereas Group 2 had more coronary interventions in the acute phase of myocardial infarction (primary or rescue), and higher use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors and thrombus aspiration catheters. The post-procedural CK-MB activity values were higher than the pre-PCI values in both groups, although Group 1 had lower values than Group 2. Procedural success was higher in Group 1 (95.1% vs. 92.5%; p=0.01)

Characteristics of procedures.

| Characteristic | Group 1 (n=1,203/1,569 vessels/1,718 lesions) | Group 2 (n=999/1,249 vessels/1,378 lesions) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treated vessels/patient | 1.3±0.6 | 1.3±0.6 | <0.01 |

| Stent/patient ratio | 1.3±0.7 | 1.1±0.7 | <0.01 |

| Stent use, n (%) | 1,419 (90.4) | 1,068 (85.5) | <0.01 |

| Drug-eluting stents | 284 (20.0) | 139 (13.0) | <0.01 |

| Stent diameter, mm | 3.00±0.48 | 3.05±0.51 | <0.01 |

| Stent length, mm | 19.1±7.1 | 19.7±6.9 | 0.06 |

| Intervention types, n (%) | <0.01 | ||

| Primary PCI | 137 (11.4) | 413 (41.3) | |

| Rescue PCI | 59 (4.9) | 131 (13.1) | |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, n (%) | 144 (12.0) | 175 (17.5) | <0.01 |

| Pre-PCI CK-MB, U/L | 34.5±84.4 | 66.9±137.8 | <0.01 |

| CK-MB 12hours post-PCI, U/L | 35.5±92.5 | 85.2±153.6 | <0.01 |

| Thromboaspiration, n (%) | 51 (4.5) | 101 (11.4) | <0.01 |

| TIMI flow, post, n (%) | <0.01 | ||

| 0/1 | 34 (2.1) | 70 (5.3) | |

| 2/3 | 1,589 (97.9) | 1,241 (94.7) | |

| Degree of stenosis, % | |||

| Pre | 85.76±12.69 | 90.22±12.83 | <0.01 |

| Post | 3.64±15.74 | 7.21±23.01 | <0.01 |

| Procedural success, n (%) | 1,144 (95.1) | 924 (92.5) | 0.01 |

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

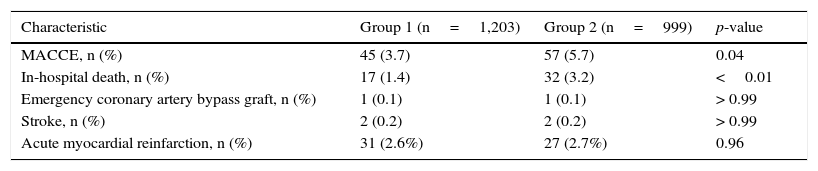

Table 4 indicates the clinical outcomes during the in-hospital phase. The occurrence of MACCE (3.7% vs. 5.7%; p=0.04) and death (1.4% vs. 3.2%; p<0.01) was more frequent in Group 2.

In-hospital clinical outcomes.

| Characteristic | Group 1 (n=1,203) | Group 2 (n=999) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACCE, n (%) | 45 (3.7) | 57 (5.7) | 0.04 |

| In-hospital death, n (%) | 17 (1.4) | 32 (3.2) | <0.01 |

| Emergency coronary artery bypass graft, n (%) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | > 0.99 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | > 0.99 |

| Acute myocardial reinfarction, n (%) | 31 (2.6%) | 27 (2.7%) | 0.96 |

MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events.

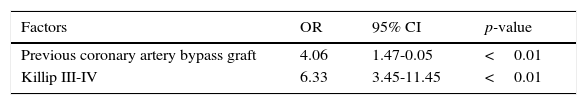

At the univariate analysis, the variables age, calcified lesions, long lesions, thrombotic lesions, previous coronary artery bypass graft, presence of collateral circulation, primary PCI, use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, pre-PCI TIMI 0/1 flow, Killip III and IV, and no use of statins showed a significant association with the occurrence of MACCE. At the multivariate analysis (Table 5), only the presence of AMI in Killip III/IV (odds ratio - OR 6.33; 95% confidence interval - 95% CI 3.45 - 11.45; p<0.01) and previous coronary artery bypass graft (OR 4.06; 95% CI 1.47 - 10.05; p<0.01) were the variables that best explained the occurrence of hospital MACCE.

DiscussionThe importance of statins in primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention comes from their lipid-lowering effects, with significant reduction in low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), as well as their pleiotropic effects, with improvement in endothelial function and anti-inflammatory and antioxidant actions, leading to atherosclerotic plaque stabilization – the latter shown as reduced atherosclerotic plaque volume by intravascular ultrasound in the REVERSAL study.7,8,21 Recently, Komukai et al. demonstrated, through optical coherence tomography, the increased atherosclerotic plaque fibrous cap thickness and lipid arc as well as macrophage reduction after treatment with atorvastatin (more significant with a 20mg dose), contributing to the pathophysiological understanding of this process.22

However, in spite of the present study's evidence, nearly half of the patients (45.3%) had no previous statin therapy, despite the presence of dyslipidemia and diabetes in almost 25%, disclosing a probable primary cardiovascular prevention failure in Brazil. The higher number of patients with AMI in this group suggests the possible clinical impact of the absence of the statin protective effect, as well as evidence that many patients start prevention (this time, secondary) only after having suffered a major event. Patients with previous statin use, despite being more complex from a clinical point of view, due to the higher frequency of prior AMI, coronary artery bypass graft, PCI, and chronic renal failure, demonstrating the prescription of statins as secondary prevention, showed a more favorable clinical profile, with ACS without ST-segment elevation predominating in this group, and lower occurrence of severe hemodynamic consequences (Killip III and IV) in those who presented with STEMI.

Another important aspect is that although the group with prior use of statins had a higher incidence of multivessel disease, more complex lesions (lesions type B2 and C, calcified lesions, lesions with thrombus, total occlusions, and TIMI 0/1 flow) were significantly more frequent in the group not receiving statins. Due to the nature of the study, it cannot be inferred that these findings are directly related to a protective effect of statins, but it can be used as a hypothesis generator.

Recent evidence has shown that high doses of statins increase their beneficial cardiovascular pleiotropic effects, which are independent from the reducing effect on cholesterol levels, as the latter only occurs with long-term treatment.23,24 The ARMYDA (Atorvastatin for Reduction of Myocardial Damage during Angioplasty), ARMYDA-ACS (Atorvastatin for Reduction of Myocardial Damage during Angioplasty-Acute Coronary Syndromes), ARMYDA-RECAPTURE (Atorvastatin for Reduction Myocardial Damage During Angioplasty), and NAPLES II (Novel Approaches for Preventing or Limiting Events II) studies, which evaluated the acute effects of atorvastatin on PCIs, showed that pre-treatment with atorvastatin significantly reduced the occurrence of periprocedural AMI.9,10,25,26 That finding, although often evidenced only by an increase in post-PCI myocardial necrosis markers, is related to increased rates of major adverse cardiac events in the follow-up.27,28 The present study showed an increase in mean post-PCI CK-MB values in both groups; patients who have made previous use of statins showed lower pre- and post-PCI values than the other group, which may indicate a cardiovascular protective effect of medication. Higher baseline values in the group that did not use statins may also be a result of a higher number of patients with STEMI.

The reduction of major adverse cardiovascular events after PCI with the use of statins has been well demonstrated in randomized studies in selected patients with no previous use of the assessed medication.9,10,12,13,25 However, the ROMA II11 and ARMYDA-RECAPTURE26 studies included patients that were chronic users of statins, who received additional high doses of atorvastatin or rosuvastatin on the day of the procedure. Interestingly, although these two studies demonstrate significant beneficial effects of the study drug on the reduction of major adverse cardiovascular events, they were not as evident as those reported in other publications. This fact would appear to demonstrate that prior use of statins could exert some protective effect on PCI results. Corroborating this hypothesis, studies of patients with STEMI have suggested that prior chronic use of statins may improve coronary flow and be associated with lower short-term mortality (30 days).14–17

In the present study with ACS patients, the procedure success rate was significantly higher in patients with previous statin use. The occurrence of TIMI 2/3 flow, which resulted in a lower incidence of clinical events in this group, reinforced the hypothesis that there may be cardiovascular protective effects of prior statin use regarding in-hospital PCI outcomes. Although the non-chronic use of statins showed a significant association with the occurrence of MACCE in the univariate analysis in this study, only the presence of STEMI in Killip III/IV and prior coronary artery bypass graft were independent predictors of in-hospital MACCE.

Study limitationsThe retrospective data analysis, the absence of late follow-up, the non-inclusion of changes in myocardial necrosis markers in the diagnosis of periprocedural reinfarction, the use of CK-MB activity to the detriment of CK-MB mass or troponin, and the lack of standardization of statin dose, type, and time of use may be considered limitations of this study.

ConclusionsPatients with acute coronary syndrome submitted to percutaneous coronary intervention who were prior statin users had better clinical outcomes. However, statin use was not an independent predictor of in-hospital major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events.

Funding sourcesNone declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review under the responsability of Sociedade Brasileira de Hemodinâmica e Cardiologia Intervencionista.