Historically, patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) have a worse prognosis than patients without prior CABG. However, more contemporary analyses have contested these findings. This study's aim was to evaluate the 30-day clinical outcomes in patients with and without prior CABG submitted to primary PCI.

MethodsProspective cohort study, extracted from the database of Instituto de Cardiologia do Rio Grande do Sul, containing 1,854 patients undergoing primary PCI.

ResultsPatients with prior CABG (3.8%) showed, in general, a more severe clinical profile. The time of symptom onset until arrival at the hospital was shorter in this group (2.50hours [1.46 to 3.66] vs. 3.99hours [1.99 to 6.50]; p<0.001), while the door-to-balloon time was similar (1.33 hour [0.85 to 2.07] vs. 1.16 hour [0.88 to 1.58]; p=0.12). Femoral access was more often used in the group with prior CABG (91.5% vs. 62.5%; p<0.001). Manual thrombus aspiration was less often performed in this group (16.9% vs. 31.1%; p=0.007), but there was no difference regarding the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (28.2% vs. 32.4%, p=0.28). Angiographic success was lower in the group with prior CABG (80.3% vs. 93.3%; p=0.009). At 30 days, patients with prior CABG had similar rates of major adverse cardiac events (14.1% vs. 11.2%; p=0.28), and mortality, although numerically higher, was not statistically significant (13.2% vs. 7.0%, p=0.07).

ConclusionsIn this contemporary analysis, patients with prior CABG undergoing primary PCI had a more severe clinical profile and lower angiographic success, but showed no differences regarding 30-day clinical outcomes.

Historicamente, pacientes com cirurgia de revascularização do miocárdio (CRM) prévia submetidos à intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP) primária têm pior prognóstico que pacientes sem CRM prévia. No entanto, análises mais contemporâneas contestam esses achados. Nosso objetivo foi avaliar os desfechos clínicos de 30 dias em pacientes com e sem CRM prévia submetidos à ICP primária.

MétodosEstudo de coorte prospectivo extraído do banco de dados do Instituto de Cardiologia do Rio Grande do Sul, contendo 1.854 pacientes submetidos à ICP primária.

ResultadosPacientes com CRM prévia (3,8%) mostraram perfil clínico, em geral, mais grave. O tempo de início dos sintomas até a chegada ao hospital foi menor nesse grupo (2,50 horas [1,46 – 3,66] vs. 3,99 horas [1,99-6,50]; p<0,001) e o tempo porta-balão foi semelhante (1,33 hora [0,85-2,07] vs. 1,16 hora [0,88-1,58]; p=0,12). O acesso femoral foi mais usado no grupo com CRM prévia (91,5% vs. 62,5%; p<0,001). O uso de tromboaspiração manual foi menor nesse grupo (16,9% vs. 31,1%; p=0,007), mas não houve diferença no uso de inibidor da glicoproteína IIb/IIIa (28,2% vs. 32,4%; p=0,28). O sucesso angiográfico foi menor no grupo com CRM prévia (80,3% vs. 93,3%; p=0,009). Aos 30 dias, pacientes com CRM prévia apresentaram taxas similares de eventos cardíacos adversos maiores (14,1% vs. 11,2%; p=0,28), e a mortalidade, embora numericamente mais alta, não foi estatisticamente significativa (13,2% vs. 7,0%; p=0,07).

ConclusõesNessa análise contemporânea, pacientes com CRM prévia submetidos à ICP primária apresentaram perfil clínico mais grave e menor sucesso angiográfico, porém não mostraram diferenças nos desfechos clínicos em 30 dias.

The number of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgeries peaked in the 1990s and currently it remains a widely used alternative revascularization method in patients with coronary atherosclerosis.1 It is also known that 50% of venous grafts become diseased, and 25% become occluded within a 5-year period postoperatively. Many of these patients seek emergency care with acute coronary syndrome.2 Epidemiological data in Brazil are scarce, but the international literature reports that, it is a relatively frequent event. According to the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR™), the percentage of patients with prior CABG who had acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation (STEMI) was around 7.0% to 7.5% between 2000 and 2010.3

The presence of prior CABG has been reported as an independent risk factor for adverse clinical outcomes in STEMI. In this scenario, diagnosis and treatment are always challenging. The clinical, electrocardiographic, and laboratory findings are not always entirely elucidative,4 and when considering the existing anatomical issues and comorbidities, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is sometimes more complex and has a worse prognosis.5

Literature data show that in patients with STEMI and prior CABG submitted to primary balloon angioplasty, in-hospital mortality rates as well as those 6 months after the event were higher when compared to patients without prior CABG, especially when the culprit vessel was a saphenous vein graft.6 There are no recent data in the national literature evaluating this group of patients in this scenario.

This study aimed to evaluate the 30-day outcomes in a contemporary cohort of patients with and without CABG, submitted to primary PCI in a tertiary referral hospital with a high volume of patients.

MethodsPatientsThis was a prospective cohort study that selected patients from an active database, which included all consecutive patients that presented with STEMI undergoing primary PCI at the Instituto de Cardiologia do Rio Grande do Sul, Fundação Universitária de Cardiologia, in Porto Alegre (RS), Brazil. The assessed data and patients were those recorded from January 2010 to December 2013. The project was approved by the local Ethics Committee. All patients were informed about the study and signed an Informed Consent.

The inclusion criteria were the presence of STEMI treated within the first 12hours. STEMI was defined as typical chest pain at rest associated with ST-segment elevation of at least 1mm in two contiguous leads in the frontal plane or 2mm in the horizontal plane, or typical chest pain at rest in patients with new, or presumably new left bundle branch block in the 12-lead electrocardiogram. Exclusion criteria were time of symptom onset until arrival at the hospital longer than 12hours, age younger than 18 years, or unwillingness to participate in the study.

Primary percutaneous coronary interventionThe decision to contact the Hemodynamics Service was made by the assistant team responsible for patient care in the emergency room, upon patient arrival. In accordance with the institutional routines, the initial adjunct antiplatelet therapy included a loading dose of 300mg of acetylsalicylic acid and a P2Y12 inhibitor (300 to 600mg of clopidogrel, 180mg of ticagrelor, or 60mg of prasugrel). The use of additional anticoagulant therapy (heparin 70 to 100 IU/kg) while still in the emergency room was performed at the discretion of the team responsible for initial care. For patients who had not received heparin in the emergency room, the drug was prescribed in the interventional laboratory by the interventional cardiology team at the time of the procedure. These professionals were also responsible for deciding whether or not use glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, as well as other adjunctive medications.

Demonstration of the culprit vessel was performed in at least two views. The access route, PCI technique, the use of thrombus aspiration, and number of stents used were left to the operator's discretion. Coronary flow before and after the procedure was evaluated according to the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) criteria.7

Data collection, outcomes and clinical follow-upAll patients were interviewed by the investigators at hospital admission. Angiographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected using a standard questionnaire. Patients were visited daily during hospital stay by one of the researchers to evaluate the occurrence of in-hospital clinical outcomes. The occurrence of cardiovascular events 30 days after the procedure was assessed by telephone contact and/or medical record review.

Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) were defined as the combination of mortality from all causes, myocardial infarction, or need for urgent revascularization. Myocardial infarction was characterized as the presence of recurrent chest pain associated with new elevation of serum biomarkers (after the initial decline in the natural curve) associated with ST-segment elevation and/or new pathological Q waves. Urgent revascularization was considered as the need to perform a new revascularization procedure, either percutaneous or surgical, due to recurrent ischemia.

Additionally, stroke was defined as the development of sudden-onset focal neurological deficit, irreversible and/or causing death within 24hours. Major bleeding was considered as the occurrence of clinically evident bleeding, a decrease in hemoglobin >5g/dL or in hematocrit >15%, or development of hemorrhagic stroke. Stent thrombosis was classified as sudden occlusion of the treated vessel, confirmed by angiography during the in-hospital stay.

Statistical analysisThe results were expressed as mean and standard deviation or absolute and relative frequencies, when appropriate. Variables with asymmetric distribution were expressed as median and interquartile range. The chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables. For continuous variables, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's test for multiple comparisons were used in the case of normal distribution, whereas the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for variables with asymmetric distribution. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed p-value<0.05.

Data were collected in a Microsoft Access database (Microsoft Corporation – Redmond, USA) and statistical analysis was performed using the tools of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 17.0 (IBM Corp.– Armonk, USA).

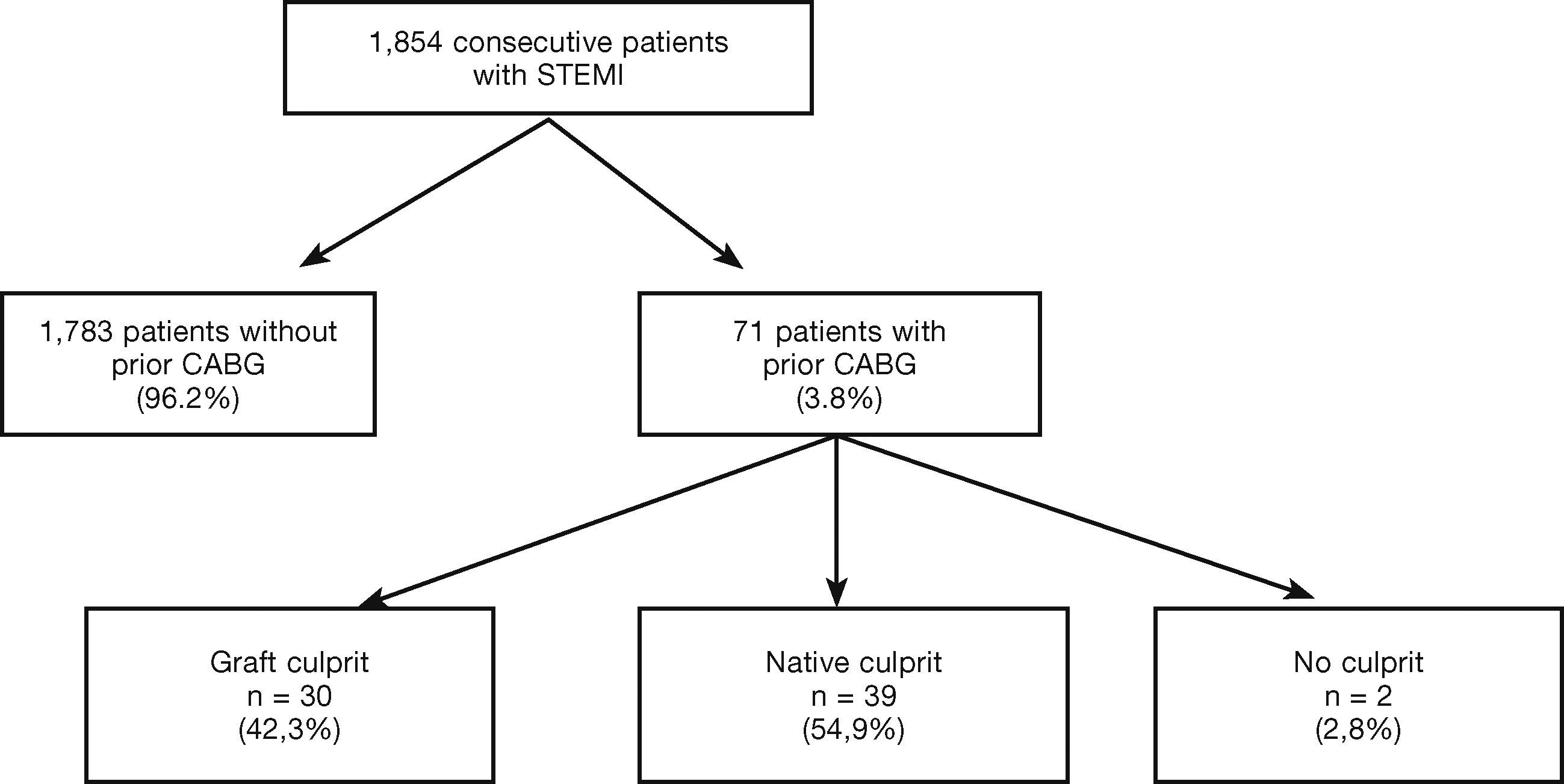

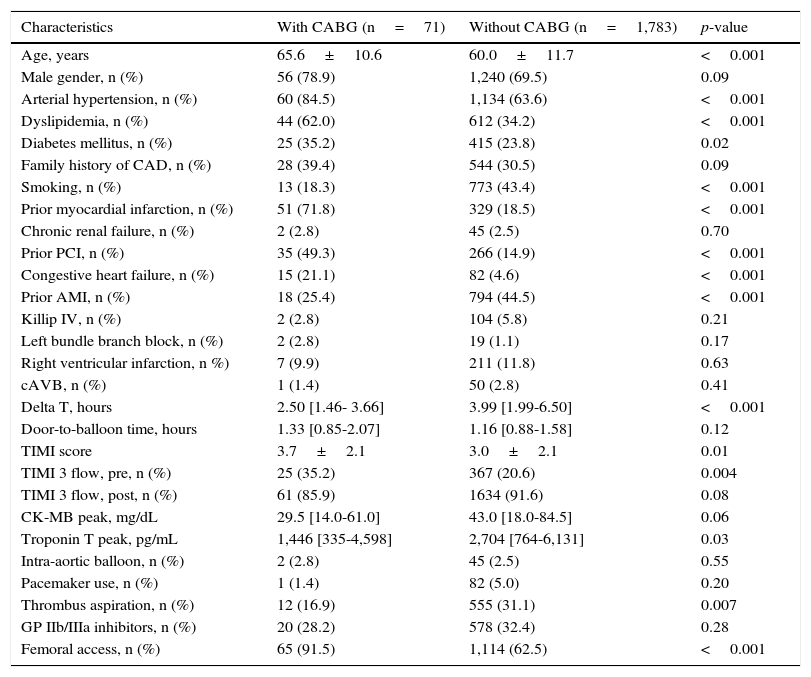

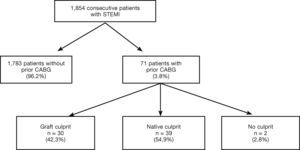

ResultsOf the 1,854 consecutive patients with STEMI and undergoing primary PCI, analyzed from 2010 to 2013, 71 (3.8%) had a history of prior CABG (Fig. 1). Table 1 describes the clinical, angiographic, and procedure characteristics. Patients with prior CABG were older, with higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension, prior acute myocardial infarction, and PCI, but there were fewer smokers and anterior wall infarctions. There were no significant differences regarding the incidence of cardiogenic shock (Killip IV), right ventricular infarction, or presence of left bundle branch block in the electrocardiogram between the groups.

Clinical, angiographic, and procedure characteristics.

| Characteristics | With CABG (n=71) | Without CABG (n=1,783) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65.6±10.6 | 60.0±11.7 | <0.001 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 56 (78.9) | 1,240 (69.5) | 0.09 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 60 (84.5) | 1,134 (63.6) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 44 (62.0) | 612 (34.2) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 25 (35.2) | 415 (23.8) | 0.02 |

| Family history of CAD, n (%) | 28 (39.4) | 544 (30.5) | 0.09 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 13 (18.3) | 773 (43.4) | <0.001 |

| Prior myocardial infarction, n (%) | 51 (71.8) | 329 (18.5) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 2 (2.8) | 45 (2.5) | 0.70 |

| Prior PCI, n (%) | 35 (49.3) | 266 (14.9) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 15 (21.1) | 82 (4.6) | <0.001 |

| Prior AMI, n (%) | 18 (25.4) | 794 (44.5) | <0.001 |

| Killip IV, n (%) | 2 (2.8) | 104 (5.8) | 0.21 |

| Left bundle branch block, n (%) | 2 (2.8) | 19 (1.1) | 0.17 |

| Right ventricular infarction, n %) | 7 (9.9) | 211 (11.8) | 0.63 |

| cAVB, n (%) | 1 (1.4) | 50 (2.8) | 0.41 |

| Delta T, hours | 2.50 [1.46- 3.66] | 3.99 [1.99-6.50] | <0.001 |

| Door-to-balloon time, hours | 1.33 [0.85-2.07] | 1.16 [0.88-1.58] | 0.12 |

| TIMI score | 3.7±2.1 | 3.0±2.1 | 0.01 |

| TIMI 3 flow, pre, n (%) | 25 (35.2) | 367 (20.6) | 0.004 |

| TIMI 3 flow, post, n (%) | 61 (85.9) | 1634 (91.6) | 0.08 |

| CK-MB peak, mg/dL | 29.5 [14.0-61.0] | 43.0 [18.0-84.5] | 0.06 |

| Troponin T peak, pg/mL | 1,446 [335-4,598] | 2,704 [764-6,131] | 0.03 |

| Intra-aortic balloon, n (%) | 2 (2.8) | 45 (2.5) | 0.55 |

| Pacemaker use, n (%) | 1 (1.4) | 82 (5.0) | 0.20 |

| Thrombus aspiration, n (%) | 12 (16.9) | 555 (31.1) | 0.007 |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors, n (%) | 20 (28.2) | 578 (32.4) | 0.28 |

| Femoral access, n (%) | 65 (91.5) | 1,114 (62.5) | <0.001 |

CABG: coronary artery bypass surgery; CAD: coronary artery disease; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; cAVB: complete atrioventricular block; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; CK-MB: creatine kinase-myocardial band; GP IIb/IIIa: glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors.

The time from symptom onset to arrival at the hospital (delta T) was significantly lower in the group with prior CABG (2.50hours [1.46 to 3.66] vs. 3.99hours [from 1.99 to 6.50]; p<0.001). The door-to-balloon time was similar in both groups (1.33 hour [0.85 to 2.07] vs. 1.16 hour [0.88 to 1.58]; p=0.12). Patients with prior CABG had higher incidence of TIMI 3 flow before the procedure, but there was a tendency to lower TIMI 3 flow after the procedure (85.9% vs. 91.6%; p=0.08). Patients with prior CABG had lower serum troponin levels than those without prior CABG, as well as a trend to a lower level of creatine kinase-myocardial band (CK-MB).

Femoral access was most often used in this group (91.5% vs. 62.5%; p<0.001). The use of manual thrombus aspiration was significantly lower in the group with prior CABG (16.9% vs. 31.1%; p=0.007); however, no difference in glycoprotein inhibitor use IIb/IIIa was observed between the two groups. Angiographic success was lower in the group with prior CABG (80.3% vs. 93.3%; p=0.009).

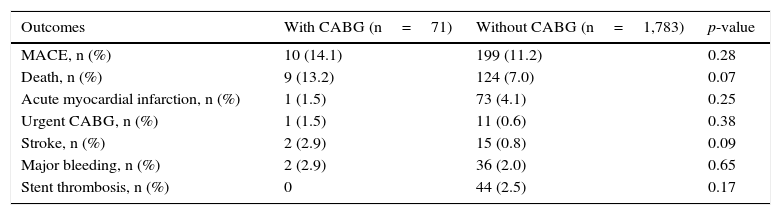

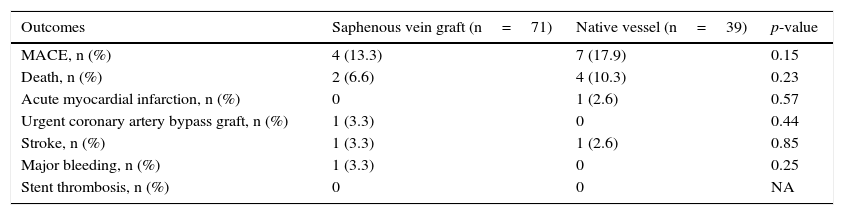

Patients with prior CABG had similar rates of MACE (14.1% vs. 11.2%; p=0.28) and mortality, which, although numerically higher, was not statistically significant (13.2% vs. 7 0%; p=0.07) when compared to patients without prior CABG (Table 2).

30-day clinical outcomes.

| Outcomes | With CABG (n=71) | Without CABG (n=1,783) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACE, n (%) | 10 (14.1) | 199 (11.2) | 0.28 |

| Death, n (%) | 9 (13.2) | 124 (7.0) | 0.07 |

| Acute myocardial infarction, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 73 (4.1) | 0.25 |

| Urgent CABG, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 11 (0.6) | 0.38 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 2 (2.9) | 15 (0.8) | 0.09 |

| Major bleeding, n (%) | 2 (2.9) | 36 (2.0) | 0.65 |

| Stent thrombosis, n (%) | 0 | 44 (2.5) | 0.17 |

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft surgery; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events.

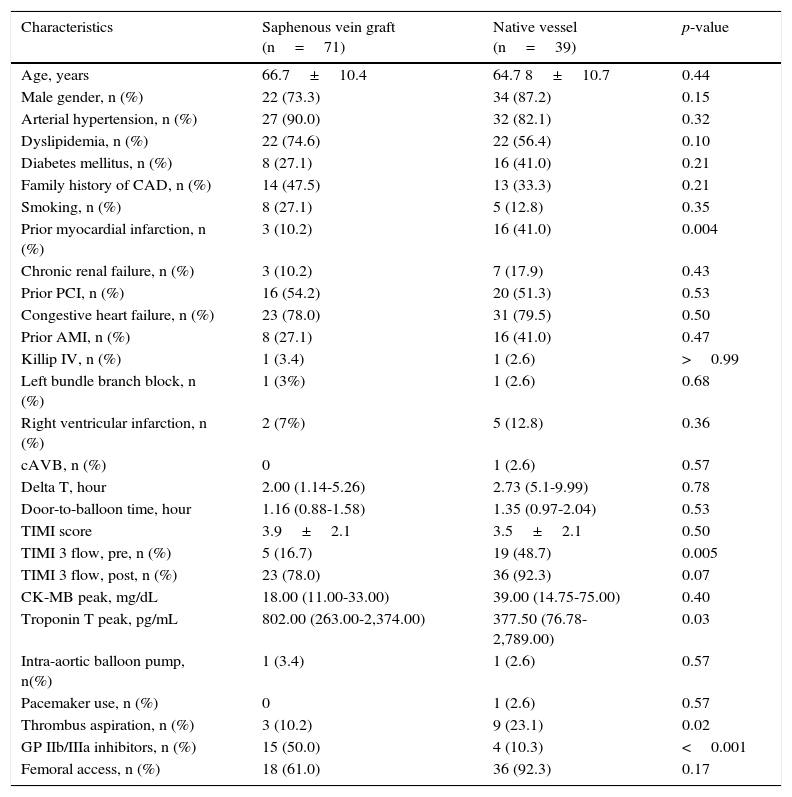

As shown in Tables 3 and 4, prior CABG patients were stratified according to the type of treated vessel. The latter was identified as a saphenous vein graft in 30 patients (42.3%), and as the native vessel in 39 patients (54.9%); the culprit vessel could not be defined in 2 patients.

Clinical characteristics among patients with prior coronary artery bypass surgery, according to the type of vessel treated.

| Characteristics | Saphenous vein graft (n=71) | Native vessel (n=39) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 66.7±10.4 | 64.7 8±10.7 | 0.44 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 22 (73.3) | 34 (87.2) | 0.15 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 27 (90.0) | 32 (82.1) | 0.32 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 22 (74.6) | 22 (56.4) | 0.10 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 8 (27.1) | 16 (41.0) | 0.21 |

| Family history of CAD, n (%) | 14 (47.5) | 13 (33.3) | 0.21 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 8 (27.1) | 5 (12.8) | 0.35 |

| Prior myocardial infarction, n (%) | 3 (10.2) | 16 (41.0) | 0.004 |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 3 (10.2) | 7 (17.9) | 0.43 |

| Prior PCI, n (%) | 16 (54.2) | 20 (51.3) | 0.53 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 23 (78.0) | 31 (79.5) | 0.50 |

| Prior AMI, n (%) | 8 (27.1) | 16 (41.0) | 0.47 |

| Killip IV, n (%) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (2.6) | >0.99 |

| Left bundle branch block, n (%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (2.6) | 0.68 |

| Right ventricular infarction, n (%) | 2 (7%) | 5 (12.8) | 0.36 |

| cAVB, n (%) | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 0.57 |

| Delta T, hour | 2.00 (1.14-5.26) | 2.73 (5.1-9.99) | 0.78 |

| Door-to-balloon time, hour | 1.16 (0.88-1.58) | 1.35 (0.97-2.04) | 0.53 |

| TIMI score | 3.9±2.1 | 3.5±2.1 | 0.50 |

| TIMI 3 flow, pre, n (%) | 5 (16.7) | 19 (48.7) | 0.005 |

| TIMI 3 flow, post, n (%) | 23 (78.0) | 36 (92.3) | 0.07 |

| CK-MB peak, mg/dL | 18.00 (11.00-33.00) | 39.00 (14.75-75.00) | 0.40 |

| Troponin T peak, pg/mL | 802.00 (263.00-2,374.00) | 377.50 (76.78-2,789.00) | 0.03 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump, n(%) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (2.6) | 0.57 |

| Pacemaker use, n (%) | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 0.57 |

| Thrombus aspiration, n (%) | 3 (10.2) | 9 (23.1) | 0.02 |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors, n (%) | 15 (50.0) | 4 (10.3) | <0.001 |

| Femoral access, n (%) | 18 (61.0) | 36 (92.3) | 0.17 |

CAD: coronary artery disease; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; cAVB: complete atrioventricular block; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; CK-MB: creatine kinase-myocardial band; GP IIb/IIIa: glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors.

30-day clinical outcomes among patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery, according to the type of vessel treated.

| Outcomes | Saphenous vein graft (n=71) | Native vessel (n=39) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACE, n (%) | 4 (13.3) | 7 (17.9) | 0.15 |

| Death, n (%) | 2 (6.6) | 4 (10.3) | 0.23 |

| Acute myocardial infarction, n (%) | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 0.57 |

| Urgent coronary artery bypass graft, n (%) | 1 (3.3) | 0 | 0.44 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (2.6) | 0.85 |

| Major bleeding, n (%) | 1 (3.3) | 0 | 0.25 |

| Stent thrombosis, n (%) | 0 | 0 | NA |

MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events; NA: not applicable.

Patients from the two groups, in general, did not show any differences in relation to clinical characteristics. Pre- (16.7% vs. 48.7%; p=0.005) and post-procedure TIMI 3 flows (78.0% vs. 92.3%; p=0.07) were lower in the venous graft group. The use of thrombus aspiration (10.2% vs. 23.1%; p=0.02) was lower, but the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was higher (50.0% vs. 10.3%; p<0.001) in this group. Angiographic success was similar (80.2% vs. 82.1%; p=0.37), as well as 30-day MACE (13.3% vs. 17.9%; p=0.15).

DiscussionThis study shows a contemporary and representative sample of patients with STEMI and prior CABG. The rate of 3.8% of patients with prior CABG found in this analysis is compatible with most reports in the literature (2.5% to 5.3%) and slightly lower than that reported in some more recent studies, in which the prior CABG rate was around 7%.8

The trend towards higher 30-day mortality in the group with prior CABG, although it may have been influenced by the sample size, suggests that these patients do not necessarily have a worse prognosis in the first 30 days after the index event. Similarly, there is no difference in MACE or mortality rate between patients with saphenous venous graft culprit lesion in relation to native vessel culprit lesion in those patients with prior CABG.

Preliminary analyses suggest increased mortality in patients with STEMI and prior CABG, especially in patients whose culprit vessel was a venous graft. A study carried out in the early 2000s showed significantly lower success rate of balloon-PCI and TIMI 3 flow after the procedure in 58 patients with prior CABG.6 Hospital mortality was higher among patients with prior CABG and in those with a venous graft as the culprit vessel. This difference between the analyses must be related to a combination of inadequate adjunct therapy, as there was no standard dual antiplatelet therapy at that time, in addition to non-routine use of stents and low success rates of reperfusion using primary PCI.

Nikolski et al.,9 in a sub-analysis of the HORIZONS-AMI study, showed that patients with prior CABG, when compared with patients with no history of surgery, had higher MACE rates at the end of 3 years, due to significant differences in reinfarction, stroke, and even mortality rates. Additionally, patients with prior CABG were associated with greater delay to mechanical reperfusion, as well as lower primary PCI rates and patency of the culprit vessel.

In another analysis, Brodie et al.10 also showed worse outcomes at 1 year and 5 years in patients with prior CABG who had the venous graft as culprit vessel. The mortality rate of this group was approximately three-fold higher when compared to those with a culprit native vessel, with statistical significance. However, this study included patients from the 1980s to the early 2000s; its main limitation is the use of stents in only 33% of cases, distal protection devices in very few patients and, above all, the absence of dual antiplatelet therapy protocol – a fact that is quite different from the current reality demonstrated in the present study, in which the optimal use of antiplatelet therapy and stent implant was the rule.

In a very recent study, Kohl et al.11 demonstrated that there was no difference in mortality between the groups with and without prior CABG in 30 days and 1 year, respectively. In the 5-year analysis, a significant increase in mortality was observed in patients with prior CABG. As observed in the present study, that study showed no differences in mortality when groups were stratified according to the culprit vessel, being either the native vessel or venous graft.

Study limitationsThis was an observational study and, therefore, definitive conclusions about the effect of certain therapies on the outcomes may have been affected by confounding bias. The number of patients included in the study, although fairly representative, may not have been enough to demonstrate differences between the two groups regarding outcomes. Additionally, these results cannot be generalized in relation to those of other centers with lower patient volumes. Angiographic analysis was not independently assessed by a different angiographic laboratory, a limitation that is also shared by other registries of patients with primary PCI. Similarly, the long-term follow-up of these patients was not carried out, which may or may not confirm the short-term findings.

ConclusionsIn this contemporary cohort of patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction with ST segment elevation, it was observed that although patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery had less angiographic success, there was no significant difference in overall mortality or in major adverse cardiac event rates in the short term, when compared to those without prior revascularization. When the group with prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery was stratified according to the culprit vessel, there was also no difference regarding the outcome between the types of treated vessels. These findings demonstrate the importance for a tertiary center to use well-defined protocols in the contemporary treatment of acute myocardial infarction with ST segment elevation, thus causing the outcomes of patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery to be similar to those of an unselected patient population. Further studies with greater power are needed to corroborate or refute these findings.

Funding sourceNone declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank their colleagues Carlos Roberto Cardoso, Cláudio Antonio Ramos de Moraes, Flavio Celso Leboute, La Hore Correa Rodrigues, and Maur o Regis Silva Moura for their participation in the primary percutaneous coronary intervention procedures.

Peer Review under the responsability of Sociedade Brasileira de Hemodinâmica e Cardiologia Intervencionista.