Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) is a potential complication after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The pathogenesis is associated to inflammatory mechanisms, endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress and the use of statins, due to their pleiotropic effects, has been investigated in this setting. We assessed whether a preload dose of rosuvastatin prior to elective PCI in patients on chronic statin reduces the incidence of CIN.

MethodsProspective, randomized, open label, single-center study. Patients were divided according to the use (group 1) or not (group 2) of rosuvastatin 40mg, 2–6 hours prior to PCI. The frequency of CIN was compared between the two groups as well as in the diabetic and renal dysfunction subgroups.

ResultsWe included 135 patients, with 60.7+9.3years of age, randomized to group 1 (n=67) or group 2 (n=68). The prevalence of diabetes was 31.1% and the prevalence of creatinine clearance < 60ml/min was 13.3%. The incidence of CIN was 8.1% and there was no difference between groups (9% vs. 7.4%; P=0.89). The incidence of CIN in diabetic patients was 15% vs. 13.6% (P=0.75) and in those with renal dysfunction it was 12.5% vs. 0 (P=0.93).

ConclusionsThe use of a preload dose of rosuvastatin at its maximum dosage did not exert a protective effect in renal function of chronic statin users undergoing elective PCI.

Impacto na Função Renal de uma Dose de Reforço de RosuvastatinaPrévia a Intervenção Coronária Percutânea Eletiva nos Pacientes em Uso Crônico de Estatina

IntroduçãoA nefropatia induzida pelo contraste (NIC) é uma complicação potencial após a intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP). A patogênese está associada a mecanismos inflamatórios, disfunção endotelial e estresse oxidativo, e as estatinas, por seus efeitos pleiotrópicos, vêm sendo analisadas nesse cenário. Avaliamos se uma dose de reforço de rosuvastatina pré-ICP eletiva, em pacientes em uso crônico de estatina, reduz a ocorrência de NIC.

MétodosEstudo prospectivo, randomizado, aberto, realizado em único centro. Os pacientes foram divididos de acordo com a utilização (grupo 1) ou não (grupo 2) de 40mg de rosuvastatina, 2 a 6 horas pré-ICP. A frequência de NIC foi comparada entre os dois grupos e nos subgrupos de diabéticos e com disfunção renal prévia.

ResultadosForam incluídos 135 pacientes, com idade de 60,7±9,3 anos, randomizados para o grupo 1 (n=67) ou para o grupo 2 (n=68). A prevalência de diabetes foi de 31,1% e de clearance de creatinina < 60ml/min, de 13,3%. A incidência de NIC foi de 8,1% e não mostrou diferença entre os grupos (9% vs. 7,4%; P=0,89). A incidência de NIC nos diabéticos foi de 15% vs. 13,6% (P=0,75) e nos portadores de disfunção renal prévia foi de 12,5% vs. 0 (P=0,93).

ConclusõesO uso de uma dose de reforço de rosuvastatina em sua posologia máxima não exerceu efeito protetor renal nos pacientes em uso crônico de estatina submetidos a ICP eletiva.

Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) is a potential complication of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). CIN is the third leading cause of in-hospital acute renal failure, occurring in approximately 7% of patients exposed to iodinated contrast agents, and usually presents spontaneous resolution. 1,2 However, CIN may be associated with a longer hospital stay, increased morbidity and mortality, and higher hospitalisation costs, especially in those patients who require renal replacement therapy. 3

The pathogenesis of CIN is not well understood but has been linked to inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress. 4 Pre-existing kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, left ventricular dysfunction, advanced age, and the use of large amounts of iodinated contrast are all major risk factors for CIN. 5,6

Statins are widely used in clinical practice for their cholesterol-lowering effects, especially in patients with atherosclerotic disease. The effects of statins, however, extend beyond cholesterol reduction and include improved endothelial function and potential anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative effects. 7

Short-term pre-treatment with statins is associated with favorable outcomes in various clinical scenarios, such as the prevention of peri-PCI myocardial injury or atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Recent studies have suggested that the pre-PCI administration of statins can also prevent the occurrence of CIN. 8

The present study sought to evaluate the effects of a preload dose of rosuvastatin prior to elective PCI in patients receiving chronic statin treatment.

METHODSThis prospective, randomized, open, single-center study included patients with coronary artery disease who were referred for the elective percutaneous implantation of at least one stent.

Those patients diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome for < 30 days, restenotic lesions, or lesions in venous or arterial grafts were excluded.

All patients included in this analysis had been receiving statin treatment for at least 30 days. After signing the informed consent, the patients were divided into two groups: those patients who would (group 1) and those who would not (group 2) receive a maximal dose of rosuvastatin (40mg) two to six hours before the PCI.

Blood samples were collected from both groups to analyse serum creatinine levels before and 24 hours after the procedure. Creatinine clearance was also evaluated before and after the procedure using the formula developed by Cockcroft & Gault. Those with a pre-PCI creatinine clearance < 60mL/min received intravenous hydration (0.9% saline, 1mL/kg/hour in the case of normal left ventricular function or 0.5mL/kg/hour in the case of left ventricular dysfunction) for at least six hours before and 12 hours after PCI, according to the institution’s protocol.

Study objectives and definitionsThe CIN frequency, variations in creatinine levels (pre-and post-Cr) and creatinine clearance rates (preand post-CrCl), and percentage variation in creatinine clearence of the two groups were compared. The subgroups containing diabetic patients with renal dysfunction were also evaluated.

CIN was defined as an absolute increase in the serum creatinine level to≥0.5mg/dL or a≥25% increase in the creatinine level in 24 hours. 5,9

Statistical analysisThe categorical data are shown as absolute numbers and percentages, and the continuous data are shown as the means±standard deviation. The categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. The continuous variables were compared with the Student’s t-test (paired and non-paired). The Mann–Whitney U test was used for the non-parametric variables. A two-tailed P-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS – Chicago, USA), release 13, was used for all analyses.

RESULTSOne hundred thirty-five patients undergoing elective PCI at the Instituto Dante Pazzanese de Cardiologia (Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil) between June of 2010 and May of 2011 who met the study inclusion criteria were randomized to group 1 (n=67) or group 2 (n=68).

The mean age of the patients was 60.7±9.3years. The prevalence of diabetes was 31.1% (n=42). The prevalence of pre-existing renal dysfunction (i.e., those patients with creatinine clearance values < 60mL/min) was 13.3% (n=18). The mean volume of contrast used per procedure was 75.5±32.1mL.

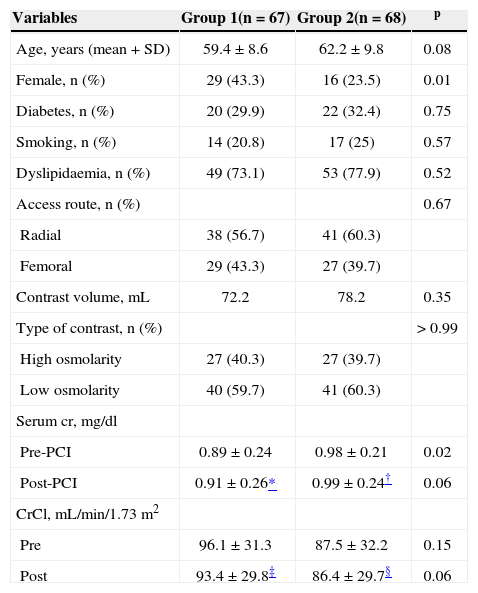

Table 1 shows the demographic and procedural variables for both of the groups. With the exception of gender, with females being more prevalent in group 1, no significant differences were observed between the two groups.

Distribution of demographic procedural variables by group

| Variables | Group 1(n=67) | Group 2(n=68) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean+SD) | 59.4±8.6 | 62.2±9.8 | 0.08 |

| Female, n (%) | 29 (43.3) | 16 (23.5) | 0.01 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 20 (29.9) | 22 (32.4) | 0.75 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 14 (20.8) | 17 (25) | 0.57 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 49 (73.1) | 53 (77.9) | 0.52 |

| Access route, n (%) | 0.67 | ||

| Radial | 38 (56.7) | 41 (60.3) | |

| Femoral | 29 (43.3) | 27 (39.7) | |

| Contrast volume, mL | 72.2 | 78.2 | 0.35 |

| Type of contrast, n (%) | > 0.99 | ||

| High osmolarity | 27 (40.3) | 27 (39.7) | |

| Low osmolarity | 40 (59.7) | 41 (60.3) | |

| Serum cr, mg/dl | |||

| Pre-PCI | 0.89±0.24 | 0.98±0.21 | 0.02 |

| Post-PCI | 0.91±0.26* | 0.99±0.24† | 0.06 |

| CrCl, mL/min/1.73m2 | |||

| Pre | 96.1±31.3 | 87.5±32.2 | 0.15 |

| Post | 93.4±29.8‡ | 86.4±29.7§ | 0.06 |

CrCl=creatinine clearance, Cr=creatinine, SD=standard deviation, PCI=percutaneous coronary

The incidence of CIN in the entire study population was 8.1% and did not differ between the two groups (9% in group 1 vs. 7.4% in group 2, P=0.89).

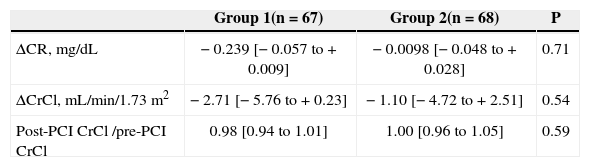

The variations in serum creatinine levels (pre-PCI vs. post-PCI) were negative, indicating increased creatinine values after the PCI procedure (group 1, mean of −0.239mg/dL, ranging from −0.057 to +0.009; group 2, mean of −0.0098mg/dL, ranging from −0.048 to +0.028; P=0.71). The variations in creatinine clearance levels (pre-PCI vs. post-PCI) were also negative, confirming the worsening of renal function after PCI (group 1, mean of −2.71mL/min/1.73m2, ranging from −5.76 to +0.23; group 2, mean of −1.10mL/min/1.73m2, ranging from −4.72 to +2.51; P=0.54). The analysis of the percentage change in creatinine clearance indicated that the values for group 1 and group 2 were both close to 1, as the variation in pre- and post-procedure creatinine clearance values was very small (group 1, mean post-CrCl/pre-CrCl=0.98, group 2, mean post-CrCl/ pre-CrCl=1.00; P=0.59). These data are shown in summarized form in Table 2.

Changes in serum creatinine levels (pre-Cr/post-Cr), creatinine clearance rates (post-CrCl/pre-CrCl), and creatinine clearance ratios (post-CrCl/pre-CrCl) in both groups

| Group 1(n=67) | Group 2(n=68) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔCR, mg/dL | −0.239 [−0.057 to +0.009] | −0.0098 [−0.048 to +0.028] | 0.71 |

| ΔCrCl, mL/min/1.73m2 | −2.71 [−5.76 to +0.23] | −1.10 [−4.72 to +2.51] | 0.54 |

| Post-PCI CrCl /pre-PCI CrCl | 0.98 [0.94 to 1.01] | 1.00 [0.96 to 1.05] | 0.59 |

Δ=variation, CrCl=creatinine clearance, Cr=creatinine

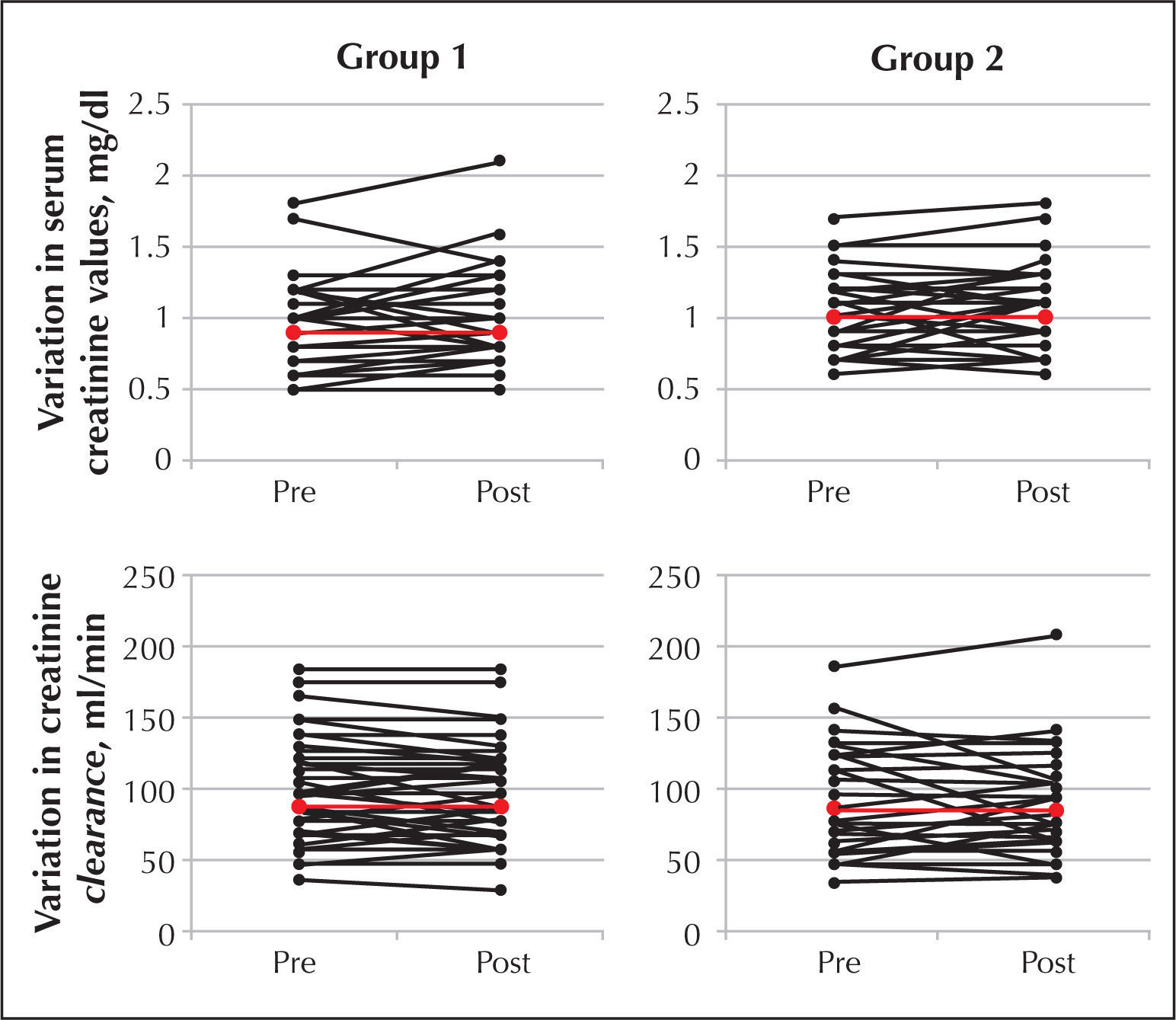

The figure shows the presence of individual variation in serum creatinine and creatinine clearance before and after PCI in both groups.

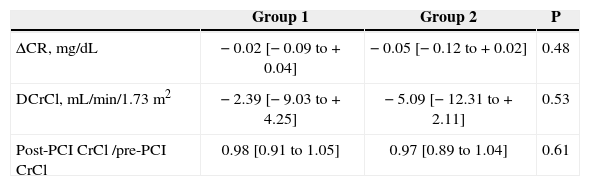

The diabetics (31.1% of the study population) were equally distributed between the two groups (29.9% vs. 32.4% for groups 1 and 2, respectively, P=0.89). The overall incidence of CIN was 14.2% and did not differ between the two groups (15% vs. 13.6% for groups 1 and 2, respectively, P=0.75). The evaluation of the variation in serum creatinine levels and creatinine clearence rates also indicated a slight worsening of renal function in the diabetic subgroup, with no statistical significance for either group (Table 3).

Variations in serum creatinine levels (pre-Cr/post-Cr), creatinine clearance rates (post-CrCl/pre-CrCl), and creatinine clearance ratios (post-CrCl/pre-CrCl) in diabetic patients

| Group 1 | Group 2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔCR, mg/dL | −0.02 [−0.09 to +0.04] | −0.05 [−0.12 to +0.02] | 0.48 |

| DCrCl, mL/min/1.73m2 | −2.39 [−9.03 to +4.25] | −5.09 [−12.31 to +2.11] | 0.53 |

| Post-PCI CrCl /pre-PCI CrCl | 0.98 [0.91 to 1.05] | 0.97 [0.89 to 1.04] | 0.61 |

Δ=variation, CrCl=creatinine clearance, Cr=creatinine

The patients with renal dysfunction (13.3% of the studied population) were equally distributed between the two groups (11.9% vs. 14.7% for groups 1 and 2, respectively; P=0.82), and the incidence of CIN in these patients was 5.6%, with no difference between the two groups (12.5% vs. 0% for groups 1 and 2, respectively; P=0.93). The serum creatinine and creatinine clearance evaluation showed positive variances and a discreet improvement in renal function in both groups; however, these values were not statistically significant (Table 4).

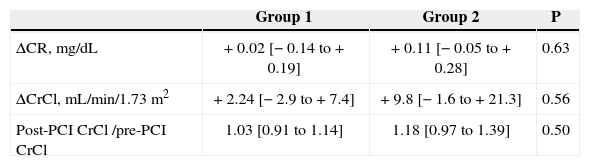

Variations in serum creatinine levels (pre-Cr/post-Cr), creatinine clearance rates (post- CrCl/pre-CrCl), and creatinine clearance ratios (post-CrCl/pre-CrCl) in patients with previous kidney disease

| Group 1 | Group 2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔCR, mg/dL | +0.02 [−0.14 to +0.19] | +0.11 [−0.05 to +0.28] | 0.63 |

| ΔCrCl, mL/min/1.73m2 | +2.24 [−2.9 to +7.4] | +9.8 [−1.6 to +21.3] | 0.56 |

| Post-PCI CrCl /pre-PCI CrCl | 1.03 [0.91 to 1.14] | 1.18 [0.97 to 1.39] | 0.50 |

Δ=variation, CrCl=creatinine clearance, Cr=creatinine

The incidence of CIN in the population of patients on chronic statin use undergoing elective PCI was 8.1%.

A maximal booster dose (40mg) of a powerful nextgeneration statin (rosuvastatin) provided two to six hours before the procedure failed to prevent the occurrence of CIN. This observation extends to the subgroups of patients with diabetes and renal dysfunction.

Several pathological mechanisms have been linked to CIN. The contrast medium stimulates the macula densa of the kidneys to produce adenosine, release angiotensin, vasopressin and endothelin, and decrease the synthesis of nitric oxide, causing hypoxia in the renal medulla. Later, other renal injury mechanisms, such as oxidative stress, the release of inflammatory cytokines, and complement activation promote the development of cellular lesions (cytoplasmic vacuolisation), necrosis, interstitial inflammation, and tubular obstruction. Statins may act during these stages to downregulate the angiotensin receptor, decrease endothelin synthesis, increase nitric oxide bioavailability, decrease the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules, limit the production of oxygen reactive species, and protect against complement-mediated injury. 8

A booster dose of rosuvastatin was administered two to six hours before the procedure to ensure that tissues were exposed to contrast medium during the peak serum concentration of rosuvastatin, which occurs approximately five hours after administration. Some anti-inflammatory effects were detected in the first 24 hours after the administration of a single 40mg dose of pravastatin.10

This and other studies evaluating the role of statins in CIN prevention have yielded different and sometimes contradictory results. However, it is necessary to understand the different methodologies and the different study populations.

For instance, in the Atorvastatin for Reduction of Myocardial Damage during Angioplasty-Contrast-Indu ced Nephropathy (ARMyDACIN) study, the administration of a high dose of atorvastatin (80mg 40 hours before and 12mg two hours before the procedure) reduced the incidence of CIN in the treatment group compared to the placebo group (5% vs. 13.2%, P=0.046). 8

However, two important considerations must be made when comparing the results of the ARMyDACIN study with this analysis: 1) the patients included in the ARMyDACIN study were not receiving any statins, 2) the study only included patients experiencing an acute coronary syndrome. In contrast, the population of the present study was already receiving chronic statin treatment and was, therefore, experiencing the pleiotropic effects of this agent. Furthermore, the patients in the present series had stable or stabilized coronary disease, unlike ARMyDACIN, in which the patients with acute coronary disease, with an enhanced inflammatory profile and associated endothelial dysfunction, may have reaped greater benefits from the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of statins.

In 2011, Zhang et al. 4 published a meta-analysis that included six registries and six randomized studies evaluating the chronic use of statins and the incidence of CIN. While four of the registries showed a nephroprotective role of statins, the randomized studies showed no statistically significant association between the use of high doses of statins for a short period and the occurrence of CIN (relative risk [RR] 0.70, 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 0.48 to 1.02), despite noticeable trend toward reduction in those receiving treatment.

Another meta-analysis published in 2011 investigated eight randomized trials with patients who were or were not receiving chronic low-dose statin treatment, finding that pre-treatment with high doses of these drugs reduced the incidence of CIN in patients with normal pre-PCI renal function (RR 0.51; 95% CI: 0.34- 0.77; P=0.001), but did not change the outcome for patients with previous renal dysfunction (RR 0.90; 95% CI: 0.49 -1.65; P=0.73). 11

Finally, the fact that a slight improvement was observed in the renal function of patients with previous renal dysfunction (creatinine clearance < 60mL/min), regardless of prior administration of rosuvastatin, deserves a brief comment. Although this study was not designed for this purpose, it is believed that this finding arose partly because this select group of patients received intravenous hydration before and after PCI, confirming the important role of hydration in the prevention of CIN.

Study limitationsA potential limitation of this study is the short post-PCI time interval during which serum creatinine levels were measured. While the studies evaluating CIN have shown that the peak increase in creatinine occurs between 48 and 72 hours after exposure to contrast medium, the measurement in this study was obtained 24 hours after PCI. However, this early assessment of renal function does not invalidate the study, as patients exhibiting serum creatinine increases of < 0.5mg/dL in the first 24 hours after exposure to contrast medium have a low probability of developing CIN. 12

Another possible limitation is the interval between the administration of rosuvastatin and the PCI procedure.

Although the pharmacokinetics of this drug indicate a peak serum concentration during the first hours after administration, it is possible that the pleiotropic effects of rosuvastatin may not occur until a later time point.

CONCLUSIONSThe administration of a maximal (40mg) booster dose of rosuvastatin to patients receiving chronic statin treatment has no renal protective effect during elective coronary angioplasty.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank the radiology technician Marcelo de Oliveira Quirino for his technical support in this work.