Anomalous origin of coronary arteries is a rare congenital disorder, with an estimated incidence of 0.3 to 1.3% of patients referred for coronary angiography. Currently, its discussion still divides opinions, particularly regarding the therapeutic approach. We report the case of a 75 year-old woman who underwent cardiac catheterization, which showed the left main coronary artery with an anomalous origin next to the right coronary artery in the right coronary sinus and with a retroaortic course.

A origem anômala de artéria coronária é uma alteração congênita rara, com incidência estimada em 0,3% a 1,3% dos pacientes encaminhados para angiografia coronariana. Atualmente, sua discussão ainda divide opiniões, principalmente quanto à abordagem terapêutica. Relatamos o caso de uma paciente de 75 anos submetida a um cateterismo cardíaco, cujo resultado mostrou tronco de coronária com origem anômala junto à coronária direita em seio coronariano direito e com trajeto retroaórtico.

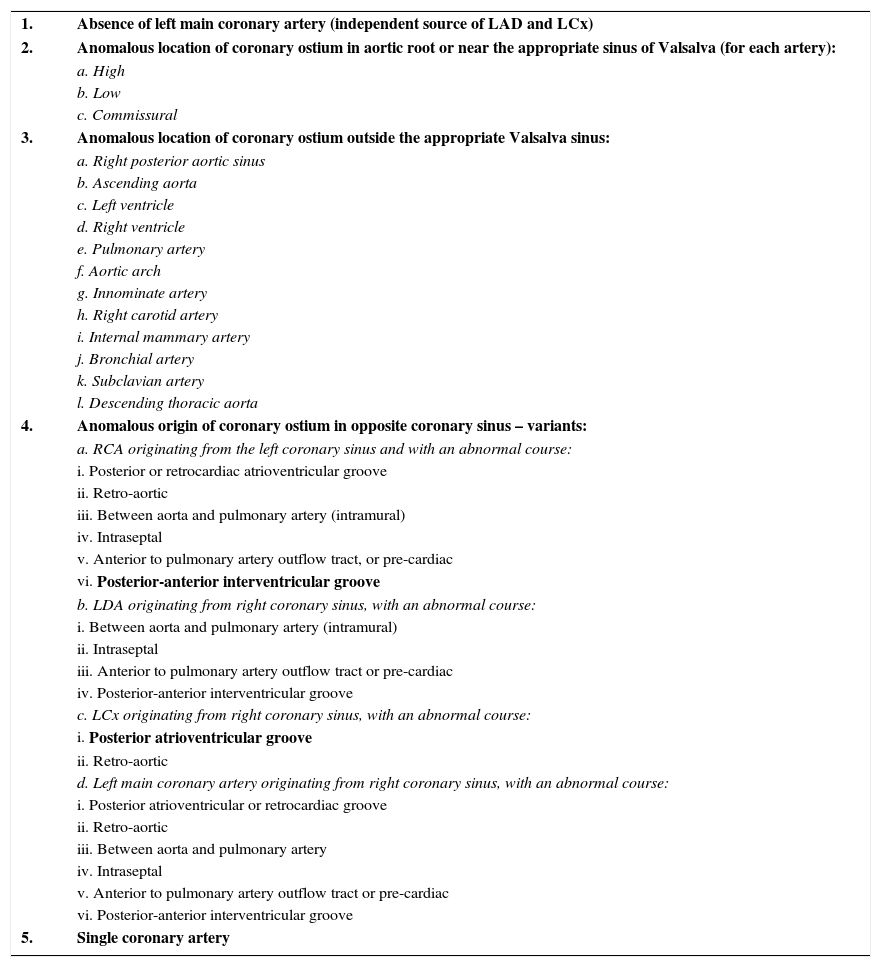

Anomalous origin of coronary artery (AOCA) is considered an uncommon congenital disorder and divides the expert opinions, especially regarding therapeutic approach. Coronary anomalies are classified, in general, into four groups: anomalies of coronary origin and course (absent left main coronary artery, anomalous location of the coronary ostium inside or outside the appropriate sinus of Valsalva, an anomalous location of the coronary ostium in an inappropriate sinus of Valsalva, and single coronary artery); intrinsic abnormalities of coronary anatomy (stenosis or atresia of coronary ostia, coronary aneurysm, coronary hypoplasia and myocardial bridge); terminal coronary flow anomalies (fistulae for heart chambers, inferior vena cava or pulmonary arteries and veins); and anomalous anastomotic vessels.1,2 Nevertheless, its presentation is a matter of concern, due to an occasional triggering of ischemic symptoms or even sudden death, especially in young adults.

Among possible presentations, single ostium of a coronary sinus is even more uncommon, and its approach is discussed according to the course of the arterial bed. This article reports the case of one of these anomalies with late presentation and peculiar angiographic imaging.

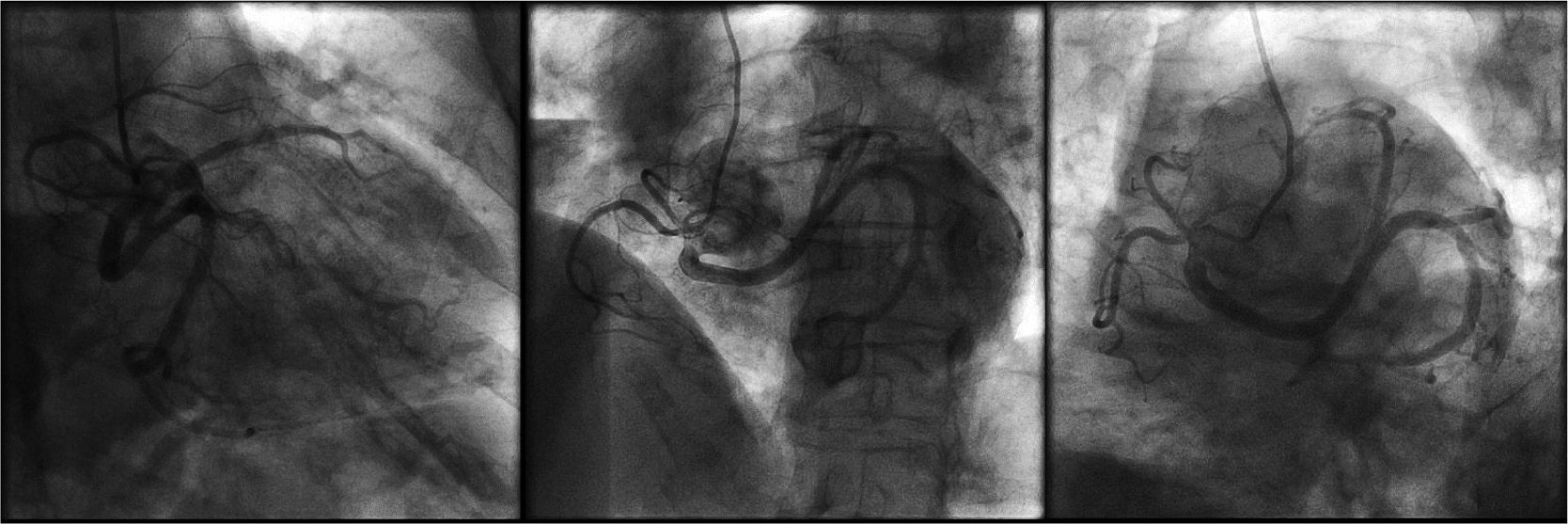

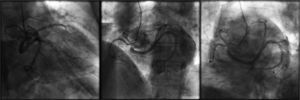

Case reportThis patient was a 75-year-old Caucasian female with history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidemia; this patient was attended with complaints of chest pain at rest. On admission, her physical examination did not show significant changes. The electrocardiogram showed a pattern of diffuse alteration of ventricular repolarization. The patient was stratified as a high-risk unstable angina and referred for coronary angiography, performed via right radial artery, which showed that the left main coronary artery ostium had an anomalous origin of the right coronary sinus with retro-aortic course (Fig. 1). The ventriculography showed ventricular hypertrophy, with preserved ejection fraction. Due to clinical stability and absence of coronary lesions, the patient was discharged with adjusted cardiovascular medication and, after 90 days, was asymptomatic and without documented ischemia on noninvasive testing.

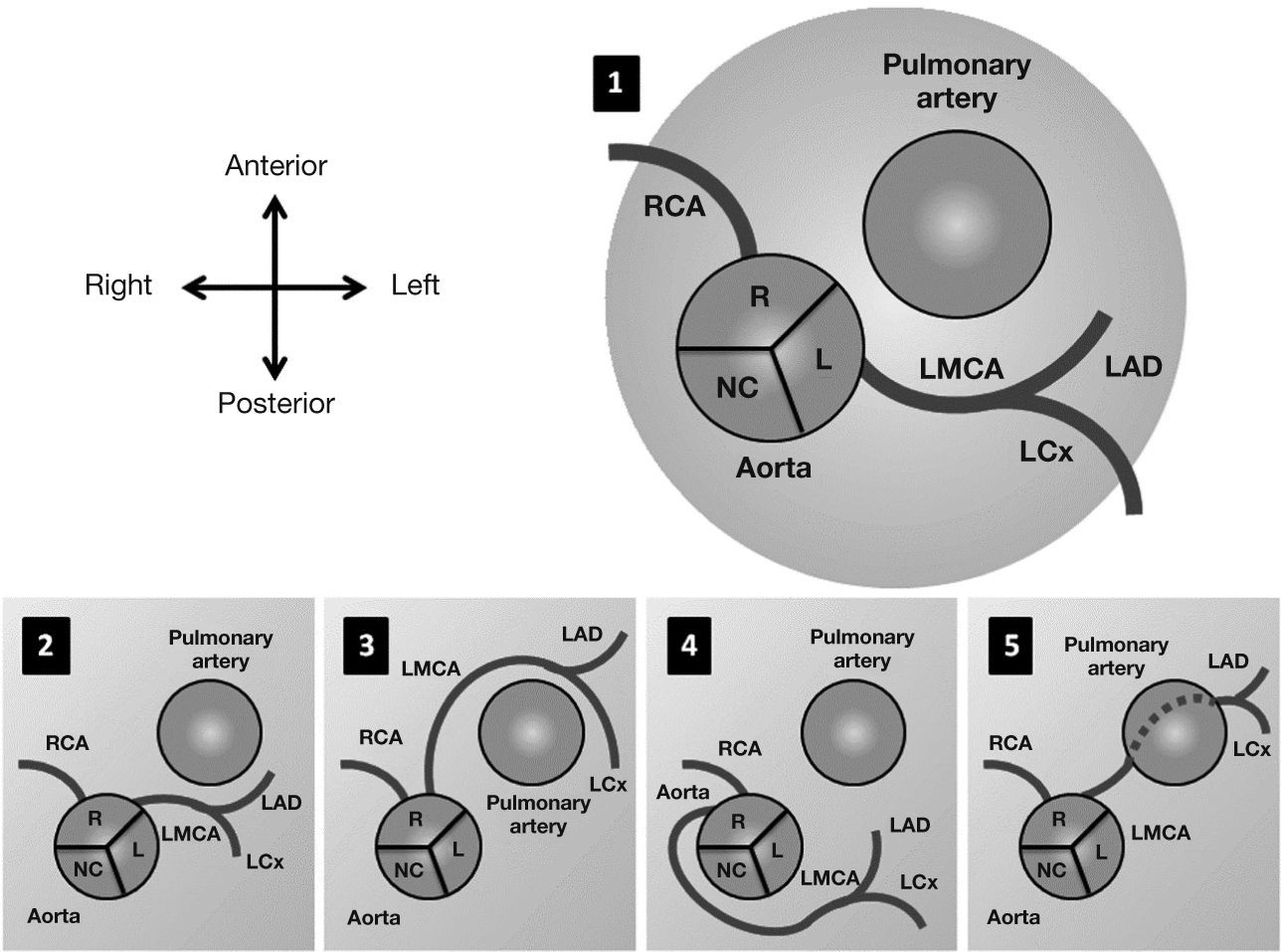

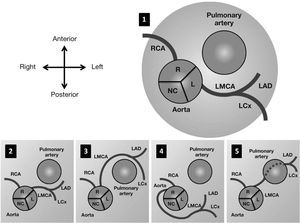

DiscussionThe first report of anomalous coronary origin was described in 1841. Such anomalies result from congenital disorders that occur around the third week of fetal development,3 and the first prospective cohort studies of coronary angiography showed a prevalence of around 5% for AOCA. Of these, 0.15% had their left coronary artery originating from the right coronary sinus.4 Currently, the classification of anomalies of coronary origin and course follows anatomical criteria (Table 1). With regard to single origin of coronary artery, more recent studies have reported that the prevalence of this particular alteration ranged between 0.1 and 0.3%,5 and this can be better understood with visualization of anatomical diagrams graphically demonstrated (Fig. 2).

Classification of coronary anomalies of origin and course.

| 1. | Absence of left main coronary artery (independent source of LAD and LCx) |

| 2. | Anomalous location of coronary ostium in aortic root or near the appropriate sinus of Valsalva (for each artery): |

| a. High | |

| b. Low | |

| c. Commissural | |

| 3. | Anomalous location of coronary ostium outside the appropriate Valsalva sinus: |

| a. Right posterior aortic sinus | |

| b. Ascending aorta | |

| c. Left ventricle | |

| d. Right ventricle | |

| e. Pulmonary artery | |

| f. Aortic arch | |

| g. Innominate artery | |

| h. Right carotid artery | |

| i. Internal mammary artery | |

| j. Bronchial artery | |

| k. Subclavian artery | |

| l. Descending thoracic aorta | |

| 4. | Anomalous origin of coronary ostium in opposite coronary sinus – variants: |

| a. RCA originating from the left coronary sinus and with an abnormal course: | |

| i. Posterior or retrocardiac atrioventricular groove | |

| ii. Retro-aortic | |

| iii. Between aorta and pulmonary artery (intramural) | |

| iv. Intraseptal | |

| v. Anterior to pulmonary artery outflow tract, or pre-cardiac | |

| vi. Posterior-anterior interventricular groove | |

| b. LDA originating from right coronary sinus, with an abnormal course: | |

| i. Between aorta and pulmonary artery (intramural) | |

| ii. Intraseptal | |

| iii. Anterior to pulmonary artery outflow tract or pre-cardiac | |

| iv. Posterior-anterior interventricular groove | |

| c. LCx originating from right coronary sinus, with an abnormal course: | |

| i. Posterior atrioventricular groove | |

| ii. Retro-aortic | |

| d. Left main coronary artery originating from right coronary sinus, with an abnormal course: | |

| i. Posterior atrioventricular or retrocardiac groove | |

| ii. Retro-aortic | |

| iii. Between aorta and pulmonary artery | |

| iv. Intraseptal | |

| v. Anterior to pulmonary artery outflow tract or pre-cardiac | |

| vi. Posterior-anterior interventricular groove | |

| 5. | Single coronary artery |

LAD: left anterior descending artery; LCx: left circumflex artery; RCA: right coronary artery.

Source: adapted from Angelini.1

Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery in right coronary sinus. Course variations. (1) Normal coronary anatomy. (2) Inter-arterial course. (3) Pre-pulmonary course. (4) Retro-aortic course. (5) Subpulmonic course. RCA: right coronary artery; R: right coronary sinus; L: left coronary sinus; NC: non-coronary sinus; LMCA: left main coronary artery; LCx: left circumflex artery; LAD: left anterior descendent artery. Source: adapted from Lim JC, Beale A, Ramcharitar S; Medscape. Anomalous origination of a coronary artery from the opposite sinus. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8(12):706-19.

The investigation of AOCA is challenging, thanks to its clinical presentation, since the first symptoms can be angina, stroke or even sudden death, especially in young people undergoing strenuous exercise.6–8 Echocardiography is a low-cost non-invasive method, and may establish the diagnosis,9 but its sensitivity and specificity decrease considerably with increasing age of the population studied, due to the difficulty with ultrasound window.

Although this is not the method of choice for diagnosis, in certain circumstances the patient with AOCA is referred still undiagnosed to the hemodynamic laboratory, and the interventionist should be acquainted with this condition for a proper anatomical explanation. In general, computed tomography angiography (CTA) provides a better visualization of anomalous coronary arteries;10 and besides CTA, coronary MRI angiography (angioresonance) is a safe and effective alternative for diagnosis of doubtful cases, although not yet with widespread use. The American Heart Association (AHA), through the document ACC/AHA 2008 Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Congenital Heart Disease, mentioned CT angiography and MR angiography in the diagnosis of AOCA, with class I indication and evidence level B.11

The existing consensus on the subject, derived mainly from the American School, indicate, when ischemia is demonstrated, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) carried out in a center of excellence in the management of AOCA,12,13 stressing the therapeutic indication, especially when the left coronary artery has its origin in the opposite coronary sinus and coursing between the aorta and the pulmonary artery, due to the risk of coronary compression by larger vessels.14 Although this is the classic mechanism described as causing ischemia, intracoronary ultrasound studies have shown that this coronary anomaly is associated with proximal intramural intussusception of ectopic artery in the aortic root wall, where hypoplasia and lateral compression of the artery segment are evidenced, which, in association with distensibility of the aortic wall, depending on intrinsic anatomic changes of the vessel wall, may explain episodic myocardial ischemia events.3,15

There is no consensus regarding the treatment of AOCA without evidence of ischemia, but the medical conduct tends to be more conservative, with betablocker and lifestyle measures in order to avoid strenuous exercise. The percutaneous option with stenting is reserved for selected cases.16

Still with respect to surgical therapy, there are differences in the literature, even on the choice of treatment; furthermore, solid evidence is lacking. Recommendations for options as surgery of reimplantation of the abnormal coronary artery to the aortic root, release of the intramural segment of the anomalous coronary artery, or the establishment of a new coronary ostium at the end of the intramural segment of the anomalous coronary (ostioplasty) were proposed.17

Funding sourcesNone declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review under the responsability of Sociedade Brasileira de Hemodinâmica e Cardiologia Intervencionista.