There are few national data on the results of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and registries are a great tool for assessing patient profiles and post-procedure outcomes. The aim of this study was to describe the profile of patients with primary PCI in a general tertiary hospital, as well as to evaluate in-hospital and 30-day cardiovascular outcomes.

MethodsThe study included all patients submitted to primary PCI between 2012 and 2015. This was a prospective registry, in which the analyzed clinical outcomes were the occurrence of death, infarction, or stroke, and major cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE).

ResultsThe study included 323 patients, aged 60 ± 12 years, of whom 66.7% were males, 28.5% diabetics. At admission, 13.5% of the patients were classified as Killip class III/IV. The pain-to-door time was 4.4 ± 2.5hours and the door-to-balloon time was 68.0 ± 34.0minutes. Hospital mortality was 9.9%, and 18.3% of the patients presented MACCE in 30 days.

ConclusionsPatients submitted to primary PCI had high rates of MACCE, which can be attributed to the more severe clinical presentation and to a long time of ischemia. The faster treatment of these patients, a modifiable variable, demands immediate attention from the health system.

Existem poucos dados nacionais a respeito dos resultados da intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP) primária, e os registros são uma ótima ferramenta para a avaliação do perfil dos pacientes e dos desfechos pós-procedimento. O objetivo deste estudo foi descrever o perfil dos pacientes com ICP primária em um hospital geral terciário, bem como avaliar os desfechos cardiovasculares hospitalares e em 30 dias.

MétodosForam incluídos todos os pacientes submetidos à ICP primária entre 2012 a 2015. Trata-se de um registro prospectivo, no qual os desfechos clínicos analisados foram a ocorrência de morte, infarto ou acidente vascular cerebral, e eventos cardiovasculares e cerebrovasculares maiores (ECCAM).

ResultadosForam incluídos 323 pacientes, com idade 60 ± 12 anos, sendo 66,7% do sexo masculino, 28,5% diabéticos. Na admissão, 13,5% dos pacientes apresentavam-se em Killip III/IV. O tempo dor-porta foi de 4,4 ± 2,5 horas e o tempo porta-balão foi 68,0 ± 34,0 minutos. A mortalidade hospitalar foi de 9,9%, e 18,3% dos pacientes apresentaram ECCAM em 30 dias.

ConclusõesOs pacientes submetidos à ICP primária apresentaram taxas elevadas de ECCAM, que podem ser atribuídas à apresentação clínica mais grave e a um longo tempo de isquemia. Um atendimento mais rápido destes pacientes, variável modificável, demanda uma atenção imediata do sistema de saúde.

Ischemic heart disease is one of the main causes of mortality, with rates of 8.8% in Brazil, having already exceeded cerebrovascular diseases in some states.1 Of the clinical manifestations of the disease, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is the one that shows higher mortality, despite the therapeutic advance in the last decades aiming to reduce its impact. In the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, in 2015, 9,185 hospital admissions for AMI were recorded, of which 2,297 occurred in Porto Alegre, the capital city.2

It is known that effective AMI treatment, through early reperfusion therapy, is the most important component of the therapeutic arsenal, being crucial for its clinical outcome, reducing the infarction size, preserving ventricular function, and decreasing morbidity and mortality.3 Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is currently the treatment of choice for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and, when compared to thrombolysis, has shown superior results in both mortality reduction and AMI recurrence.4,5

There are few data on the results of primary PCI in patients treated by the Unified Health System (SUS, acronym in Portuguese), which, due to limited funding, does not use advanced treatments and is likely to show results that are very different from those seen in clinical trials carried out in developed countries. Additionally, the lack of planning and logistics causes patients to be treated at tertiary referral centers at a very late stage, increasing their morbidity and mortality.

This study aimed to describe the clinical, angiographic, and procedural profile of patients submitted to primary PCI treated at a general tertiary hospital, as well as to evaluate in-hospital and 30-day cardiovascular outcomes.

MethodsStudy design and patient selectionThis was a prospective registry that included all patients treated with primary PCI in an interventional cardiology unit of a tertiary hospital between 2012 and 2015.

The project was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, and the patients signed the Free and Informed Consent Form. The data were recorded prospectively in appropriate forms, stored in electronic spreadsheets, and subsequently collected in a database.

Periprocedural aspectsPatients were pre-treated with 300mg of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), a loading dose of 600mg of clopidogrel, and 70 to 100 IU/kg of intravenous unfractionated heparin. Use of IIb/IIIa glycoprotein inhibitors, aspiration thrombectomy, and percutaneous intervention strategies (pre-dilation, direct stenting, and post-dilation) were performed at the interventionist's discretion. Anticoagulants were discontinued after the procedure (except in cases with absolute indication), and dual antiplatelet therapy, including ASA 100mg daily and clopidogrel 75mg daily, was recommended for 12 months after the event.

Study outcomesThe analyzed clinical outcomes were death, stroke, reinfarction, or need for emergency revascularization, isolated or combined. Stent thrombosis, contrast-induced nephropathy (relative increase in basal creatinine ≥ 25% and/or ≥ 0.5mg/dL 48 to 72hours post-catheterization),6 class III or IV heart failure (according to the New York Heart Association – NYHA – classification), and angina class III or IV (according to the Canadian Cardiovascular Society – CCS – criteria) were also recorded. Clinical follow-up was performed through outpatient consultation or telephone contact.

Angiographic analysisCoronary angiography was performed using the Axiom Artis equipment (Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlagen, Germany). Angiographic analyses were performed by experienced interventional cardiologists, through visual estimation, in at least two orthogonal projections. The initial and final Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow were determined, and the anatomic complexity was assessed using the SYNTAX angiographic score. To calculate the SYNTAX score, each coronary lesion with luminal obstruction > 50% in vessels ≥ 1.5mm was scored and, at the end, all lesions were added in accordance with the specified recommendations.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were described as mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables were shown as absolute and percentage numbers, and compared using the Chi-squared or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate.

To perform the multivariate analysis, the isolated effect of each variable was initially investigated by simple logistic regression models (univariate analysis). Subsequently, the variables with p < 0.10 in the univariate analysis were evaluated simultaneously in a multiple logistic regression model (multivariate analysis). For qualitative independent variables, the reference category was considered that with the lowest frequency of complications. The results were expressed as relative risk (RR) and the respective 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

All data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) program, version 17.0.

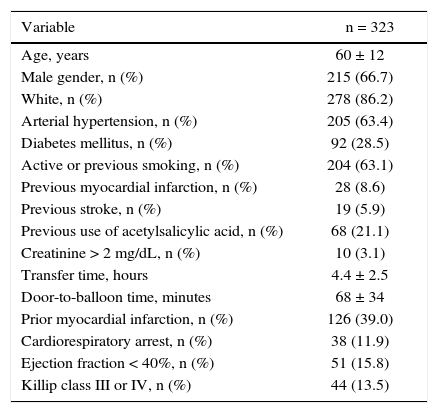

ResultsA total of 323 patients submitted to primary PCI performed at Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre from January 2012 to December 2015 were included. The mean age was 60 ± 12 years, 66.7% of the patients were males and 28.5% were diabetics (Table 1).

Clinical characteristics.

| Variable | n = 323 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 60 ± 12 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 215 (66.7) |

| White, n (%) | 278 (86.2) |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 205 (63.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 92 (28.5) |

| Active or previous smoking, n (%) | 204 (63.1) |

| Previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 28 (8.6) |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 19 (5.9) |

| Previous use of acetylsalicylic acid, n (%) | 68 (21.1) |

| Creatinine > 2 mg/dL, n (%) | 10 (3.1) |

| Transfer time, hours | 4.4 ± 2.5 |

| Door-to-balloon time, minutes | 68 ± 34 |

| Prior myocardial infarction, n (%) | 126 (39.0) |

| Cardiorespiratory arrest, n (%) | 38 (11.9) |

| Ejection fraction < 40%, n (%) | 51 (15.8) |

| Killip class III or IV, n (%) | 44 (13.5) |

Patients had a transfer time of 4.4 ± 2.5hours and door-to-balloon time of 68 ± 34minutes. The median ischemia time was 5.1 [3.7-6.9] hours. Of the patients included, 74% were referred from other health units, and 29.3% of them were transferred by the Emergency Mobile Service (SAMU, acronym in Portuguese).

At admission, 11.6% of the patients were classified as Killip class IV, 11.1% required a periprocedural temporary pacemaker, and 4.1% needed an intra-aortic balloon pump. Cardiorespiratory arrest before or after the procedure occurred in 11.9% of the patients.

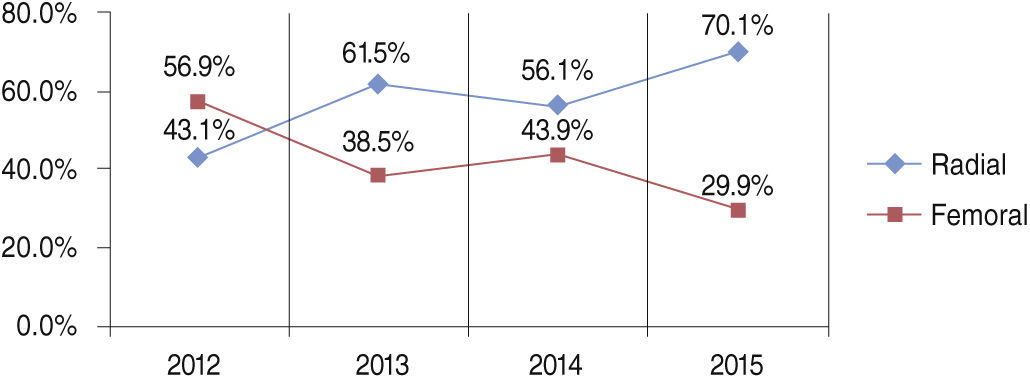

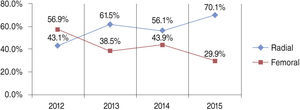

The radial access was used in 60.1% of cases, with increasing use over the period (from 43.1% in 2012 to 70.1% in 2015) (Fig. 1).

In approximately 57% of the cases, the infarction was located in the inferior wall, and in 40.5% of them the right coronary was the culprit artery. Over half (55.1%) of the patients had more than one vessel with coronary artery disease, of whom 10.9% were treated during the same procedure (ad-hoc) and 31.3% were treated at the same hospital stay.

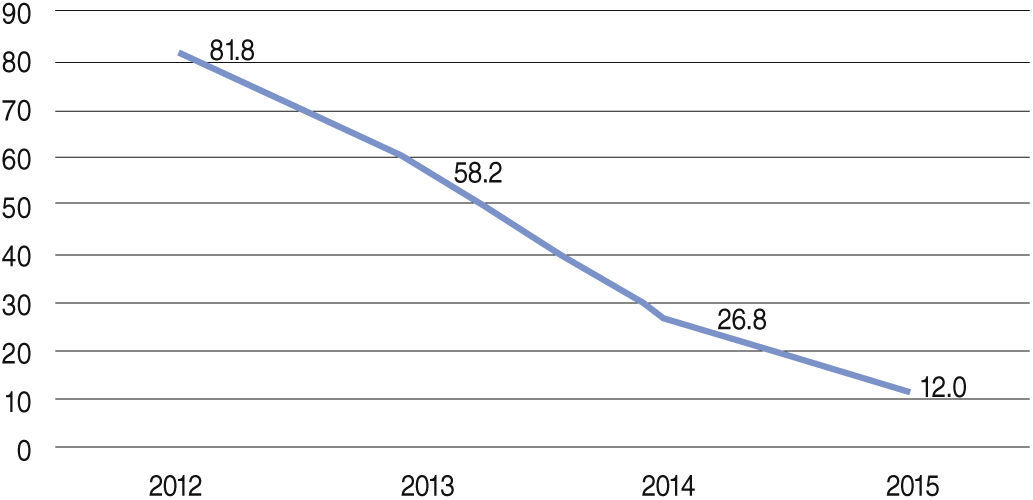

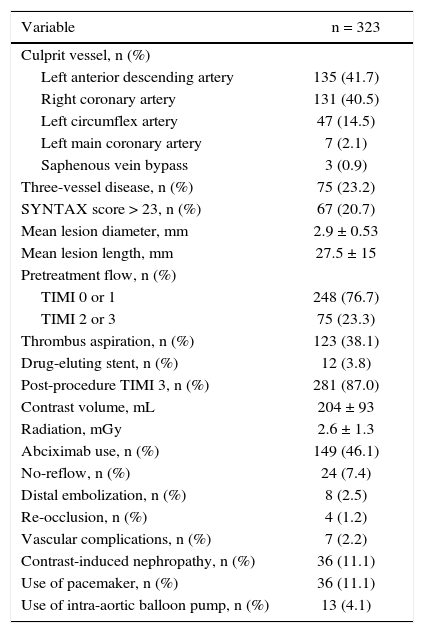

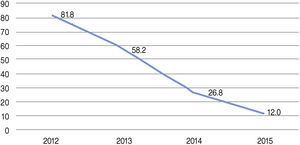

The mean number of implanted stents was 1.29 ± 0.75. Aspiration thrombectomy was performed in 38.2% of patients during the period, with progressively lower rates over the years (from 81.8% in 2012 to 12% in 2015) (Fig. 2). TIMI 3 flow was obtained in 87.0% of the cases, and TIMI 2 or 3 in 95.9% of the cases (Table 2).

Angiographic and procedural characteristics.

| Variable | n = 323 |

|---|---|

| Culprit vessel, n (%) | |

| Left anterior descending artery | 135 (41.7) |

| Right coronary artery | 131 (40.5) |

| Left circumflex artery | 47 (14.5) |

| Left main coronary artery | 7 (2.1) |

| Saphenous vein bypass | 3 (0.9) |

| Three-vessel disease, n (%) | 75 (23.2) |

| SYNTAX score > 23, n (%) | 67 (20.7) |

| Mean lesion diameter, mm | 2.9 ± 0.53 |

| Mean lesion length, mm | 27.5 ± 15 |

| Pretreatment flow, n (%) | |

| TIMI 0 or 1 | 248 (76.7) |

| TIMI 2 or 3 | 75 (23.3) |

| Thrombus aspiration, n (%) | 123 (38.1) |

| Drug-eluting stent, n (%) | 12 (3.8) |

| Post-procedure TIMI 3, n (%) | 281 (87.0) |

| Contrast volume, mL | 204 ± 93 |

| Radiation, mGy | 2.6 ± 1.3 |

| Abciximab use, n (%) | 149 (46.1) |

| No-reflow, n (%) | 24 (7.4) |

| Distal embolization, n (%) | 8 (2.5) |

| Re-occlusion, n (%) | 4 (1.2) |

| Vascular complications, n (%) | 7 (2.2) |

| Contrast-induced nephropathy, n (%) | 36 (11.1) |

| Use of pacemaker, n (%) | 36 (11.1) |

| Use of intra-aortic balloon pump, n (%) | 13 (4.1) |

TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

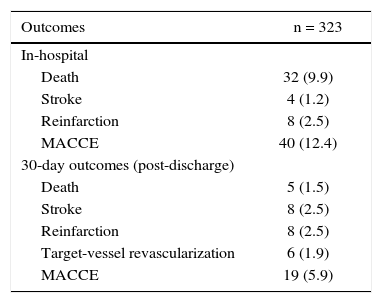

The in-hospital mortality rate was 9,9%. When analyzing only those patients who did not have cardiorespiratory arrest and were classified as Killip class I and II on admission, the in-hospital mortality was reduced to 4.3%, compared to 52.8% of patients who had cardiorespiratory arrest and/or were at Killip class III or IV on admission (p < 0.01). During hospitalization, 2.5% of the patients had reinfarction and 2.5% had a stroke.

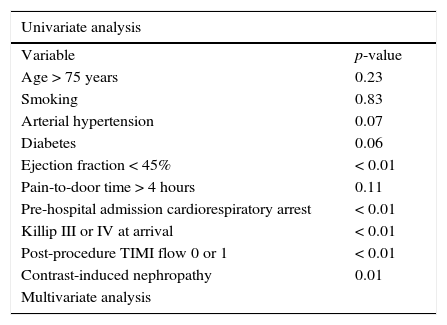

At the 30-day follow-up, 8.6% of the patients had recurrent angina, and 7.8% required hospital readmission for decompensated heart failure. Combined cardiovascular outcomes occurred in 18.3% of the patients (Table 3). The following variables were predictors of combined cardiovascular outcomes in the present study: left ventricular ejection fraction < 45% (p < 0.01), Killip class III or IV on admission (p < 0.01), as well as the occurrence of cardiorespiratory arrest (p< 0.01), TIMI flow 0 or 1 after PCI (p < 0.01) and contrast-induced nephropathy (p = 0.01). Of these, only reduced coronary flow after the procedure (TIMI flow 0 or 1) was an independent predictor of risk after the multivariate analysis (RR 4.91, 95%CI: 1.40-17.2, p = 0.01) (Table 4).

In-hospital and 30-day clinical outcomes.

| Outcomes | n = 323 |

|---|---|

| In-hospital | |

| Death | 32 (9.9) |

| Stroke | 4 (1.2) |

| Reinfarction | 8 (2.5) |

| MACCE | 40 (12.4) |

| 30-day outcomes (post-discharge) | |

| Death | 5 (1.5) |

| Stroke | 8 (2.5) |

| Reinfarction | 8 (2.5) |

| Target-vessel revascularization | 6 (1.9) |

| MACCE | 19 (5.9) |

MACCE: major cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events.

Predictors of combined cardiovascular outcomes in 30 days.

| Univariate analysis | |

|---|---|

| Variable | p-value |

| Age > 75 years | 0.23 |

| Smoking | 0.83 |

| Arterial hypertension | 0.07 |

| Diabetes | 0.06 |

| Ejection fraction < 45% | < 0.01 |

| Pain-to-door time > 4 hours | 0.11 |

| Pre-hospital admission cardiorespiratory arrest | < 0.01 |

| Killip III or IV at arrival | < 0.01 |

| Post-procedure TIMI flow 0 or 1 | < 0.01 |

| Contrast-induced nephropathy | 0.01 |

| Multivariate analysis | |

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-procedure TIMI flow 0 or 1 | 4.91 | 1.40-17.2 | 0.01 |

| Ejection fraction < 45% | 1.56 | 0.82-2.96 | 0.16 |

| Killip III or IV at arrival | 2.33 | 0.91-5.91 | 0.07 |

| Pre-hospital admission cardiorespiratory arrest | 1.90 | 0.87-3.04 | 0.87 |

| Contrast-induced nephropathy | 1.91 | 0.76-4.78 | 0.16 |

TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; HR: hazard ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval.

Much of the data regarding primary PCI comes from randomized controlled trials with strict patient control. The extrapolation of these data into the real world might not be representative, especially in a healthcare system with limited resources such as SUS.7,8

In the present study, patients presented a very high baseline risk, greater severity of clinical signs on admission, and higher morbidity and mortality (11.5% of patients in Killip class IV), in addition to a large number of patients with multivessel disease, resulting in high rates of combined cardiovascular outcomes. When comparing the present data with a French registry of patients with STEMI,9 the rates of hypertension (63% vs. 47%), diabetes (18% vs. 28%), smokers (52% vs. 43%), and previous history of stroke (6% vs. 3%) were higher in the present study. Although the angiographic success rate after the procedure (defined as TIMI flow 2 or 3) was 95.9%, similar to that found in large AMI registries,8–11 the morbidity and mortality rates in the present study were higher, probably due to the increased risk profile of the patients. When analyzing only those patients who did not have cardiorespiratory arrest and who were classified as Killip class I and II on admission, in-hospital mortality decreased to 4.3%, similar to the aforementioned registries. Although the clinical presentation in Killip class III or IV on admission was not an independent predictor of combined cardiovascular outcomes, a statistical trend was observed; it is likely that this variable would become significant with a larger sample. A matter of concern observed in the present study, which may be related to the higher severity and worse prognosis of patients, was the long period between the symptom onset and coronary reperfusion. It is known that the time of myocardial ischemia is related to myocardial viability after reperfusion and subsequent clinical outcomes.3 A recent study corroborated these data by showing an increase in long-term mortality, mainly in patients with anterior AMI and ischemia time > 114minutes.12 The mean time of ischemia in the present study was 5.5hours, approximately 2hours longer than that seen in the studies conducted in developed countries.8–11 In addition to having a poorly organized AMI treatment network concerning referrals and referral hospitals, healthcare units do not have fibrinolytic agents, which could allow prompt coronary reperfusion and reduce adverse outcomes. Moreover, prehospital thrombolysis is known to be beneficial, improving outcomes and cost-effectiveness.13 Caluza et al.14 showed a reduction in mortality in patients with AMI treated in a municipal treatment network with electrocardiogram interpretation by telemedicine and prehospital thrombolysis. Although the incidence of AMI in the metropolitan region of Porto Alegre has remained stable in recent years,1 the increase in the number of cases in the last year of the analysis (50% higher in 2015 than in 2014) is probably due to healthcare system failures, with a scarcity of funds and consequent closing/restriction of other cardiologic emergency units in this city.

This analysis also showed a change in institutional practices, in accordance with the innovations presented in the literature. During the study period, there was an important increase in the use of radial access when performing PCI. In 2012, the RIFLE13 study was published, reporting a reduction in mortality with the radial access route in patients with STEMI. In 2012, the rate of radial access in the cases included in the present study was 41.9% and it increased to 61.5% in the following year; currently, it is around 70%. Another important data from the analysis was the significant reduction in the performance of aspiration thrombectomy. The rates, which were 83% in 2012, decreased significantly in 2014, following the publication of the TASTE15 study, which suggested the non-effectiveness of the device as an adjuvant in primary PCI. In 2014, the TOTAL16 study was published, which showed an increase in stroke rates without reducing other outcomes with routine thrombectomy. Currently, the procedure is still performed in 12% of patients, because, as recommended by AMI guidelines,17,18 the method can still be performed in selected cases (high thrombotic load and slowed coronary flow).

Study limitationsThe present study has limitations that are inherent to observational studies. Some data were obtained retrospectively and others through telephone contact, which may indicate less reliable information. Moreover, there were limitations due to the relatively small sample size and the short follow-up. However, this study was a registry of consecutive and unselected patients from a tertiary referral hospital for the treatment of acute coronary syndromes, so the data shown here are highly applicable to daily clinical practice.

ConclusionsIn the present study, patients submitted to primary percutaneous coronary intervention had high rates of adverse cardiovascular outcomes, which can be attributed to the more severe clinical presentation on admission and delayed start of reperfusion therapy. Therefore, faster and more adequate patient care, considering it is a modifiable variable, demands immediate attention from the healthcare system.

Funding sourcesFundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa e Eventos of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer review under the responsibility of Sociedade Brasileira de Hemodinâmica e Cardiologia Intervencionista.