Edited by:

Diego Sauka - Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Argentina

Leopoldo Palma - Universidad de Valencia, Spain

Johannes Jehle - Julius Kühn-Institut, Institute for Biological Control, Germany

Last update: October 2025

More infoThis paper systematically reviews the taxonomic characteristics, pest control mechanisms, and field application cases of Trichoderma harzianum. As a non-toxic and environmentally friendly biocontrol fungus, T. harzianum exerts its pest control effects through various modes of action, including direct actions (such as parasitism, the production of insecticidal metabolites, and the release of antifeedant and repellent compounds) and indirect actions (such as inducing plants to enhance their resistance, attracting natural enemies of pests, and affecting insect symbiotic fungi). It can effectively control various agricultural pests, including nematodes and aphids. Moreover, the paper focuses on analyzing how modern formulation technologies (e.g., microencapsulation), synergistic strategies (in combination with biological and/or chemical agents), and genetic engineering enhance its biocontrol efficiency. This study aims to provide a theoretical basis and technical reference for constructing a sustainable pest management system based on T. harzianum, addressing pest control challenges within the context of increasing global food demand and supporting sustainable agricultural development.

Este trabajo revisa sistemáticamente las características taxonómicas, los mecanismos de control de plagas y los casos de aplicación en campo de Trichoderma harzianum. Como hongo de biocontrol no tóxico y respetuoso con el medio ambiente, T. harzianum ejerce su efecto de control de plagas a través de diversos mecanismos de acción, que incluyen acciones directas (como el parasitismo, la producción de metabolitos insecticidas y la liberación de compuestos antialimentarios y repelentes) y acciones indirectas (como inducir a las plantas a mejorar su resistencia, atraer enemigos naturales de las plagas y afectar a los hongos simbióticos de los insectos). T. harzianum puede controlar eficazmente diversas plagas agrícolas, incluidos nematodos y áfidos. Además, el trabajo se centra en analizar cómo las tecnologías modernas de formulación (por ejemplo, la microencapsulación), las estrategias sinérgicas (en combinación con agentes biológicos y/o químicos) y la ingeniería genética mejoran su eficiencia de biocontrol. Este estudio tiene como objetivo proporcionar una base teórica y una referencia técnica para la construcción de un sistema sostenible de manejo de plagas basado en T. harzianum, abordando los desafíos del control de plagas en el contexto de una demanda mundial creciente de alimentos y apoyando el desarrollo agrícola sostenible.

According to the World Population Prospects 2024 report published by the United Nations, the global population is projected to reach 9 billion by 2050, consequently leading to rapid growth in food demand, which places higher requirements on agricultural production82,88. In contemporary agriculture, crop yield enhancement depends on multiple factors, such as the recommended application of fertilizer to provide a nutrient foundation for crops, improved crop varieties to enhance production potential, and effective disease control and pest management to safeguard optimal crop growth environments. According to statistics, approximately 45% of global production is lost annually due to insect pests, and pest management has become one of the core challenges in the sustainable development of agriculture44,77.

Over recent decades, the extensive and repeated application of chemical pesticides has significantly impacted the environment and posed direct threats to human health and survival51. Consequently, as concerns regarding the environmental and health repercussions of chemical pesticide use intensify, research in pest management is increasingly focusing on sustainable and eco-friendly alternatives, with particular emphasis on biopesticides as a pivotal strategy40. Biopesticides, a category of pest control agents derived from organisms, primarily include microbial pesticides, biochemical pesticides, and plant-incorporated protectants14. Microbial pesticides not only facilitate nutrient uptake and enhance tolerance to abiotic stresses, but also mitigate biotic stresses both above and below ground, thereby offering potential for pest control and the promotion of crop growth and health5,11.

In recent years, fungi belonging to the genus Trichoderma have increasingly become a focal point of research due to their non-toxic, broad-spectrum, and environmentally friendly characteristics42. As of 2024, there are 541 Trichoderma spp. recognized with valid nomenclature6. Several species within this genus, such as T. harzianum, T. longibrachiatum, T. viride, and T. atroviride, have been confirmed to possess pest control capabilities and can to act as safe and sustainable antagonistic agents against pests7,17,26,73. Among these, as a plant-beneficial fungus, T. harzianum not only enhances plant growth after colonizing plant roots, but also helps plants cope with the invasion of plant pests and diseases through complex mechanisms. It is currently one of the most thoroughly studied species in the genus Trichoderma90.

This study systematically reviews the taxonomic characteristics, pest control mechanisms, and field applications of T. harzianum, emphasizing how modern formulation technologies, synergistic strategies, and genetic engineering enhance its biocontrol efficacy. The objective of this review is to provide a theoretical foundation and a technical reference for developing a sustainable pest management system centered on T. harzianum.

Trichoderma harzianum control of agricultural pestsTrichoderma harzianum overviewTrichoderma harzianum, a filamentous fungus within the Ascomycota phylum, the Hypocreaceae family, and the Trichoderma genus, is extensively utilized in biological control applications15. This fungus is commonly found in moist environments such as forests, ravines, farmlands, and grasslands, and can exist in various substrates, including soil, other fungi, and decaying plant residues38,92. The fungal colony typically exhibits a circular morphology, characterized by a dense green spore disk centrally located, encircled by one to two broad concentric rings covered with a cotton-wool-like mycelium. Occasionally, it exhibits radial growth. T. harzianum conidiophores are pyramidal, with symmetrical branching along the main axis. Branch termini form cross-shaped or whorled bottle-shaped cells10,12. Conidia are smooth, spherical, and generally aggregated in clusters. T. harzianum primarily acts as a root endophyte, predominantly colonizing the outermost root layer. It is mainly employed to manage a diverse array of plant pathogens and pests3,5,11. Presently, its application spans a variety of crops, including tomato, corn, soybean, eggplant, and zucchini17,45,50,84.

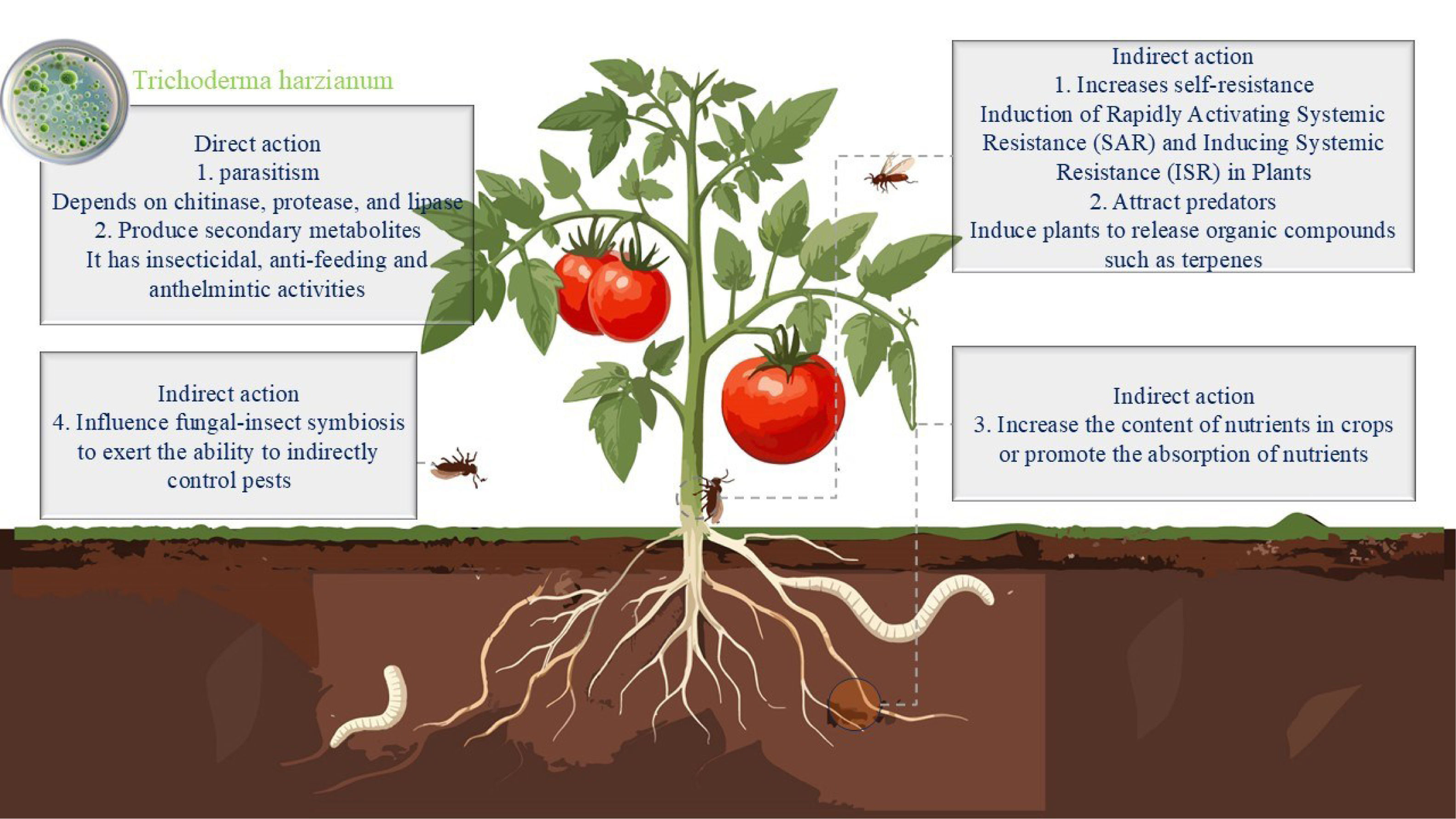

Mode of action of Trichoderma harzianum on insectsTrichoderma harzianum has demonstrated significant potential in managing various agricultural pests through diverse mechanisms of action. Recent studies have shown its remarkable efficacy against a wide range of agricultural pests, including those in the classes Nematoda, Insecta (Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Hemiptera, among others), Arachnida, and Gastropoda3,9,16,17,46,72,84. These studies not only expand the application scope of biocontrol agents but also reveal its complex pest-control network of “direct action-indirect regulation”. However, compared to its broad application prospects, research on the specific pest-control mechanisms of Trichoderma spp. remains insufficient; most studies still rely on inferences based on evolutionary homology with other entomopathogenic fungi49, highlighting an urgent need for systematic mechanistic analysis and scientific validation. Specifically, the pest-control modes of action of T. harzianum can be categorized into direct and indirect effects (Figure 1).

Direct actionTrichoderma harzianum affects pests through a variety of direct mechanisms, mainly parasitism, production of insecticidal metabolites, the release of antifeedant compounds and repellent metabolites.

ParasitismTrichoderma harzianum is capable of adhering to pest surfaces and subsequently disrupting the pest cuticle through mechanical or enzymatic processes. After invasion, the fungus grows within the host and secretes toxic compounds that eventually lead to the death of the pest. In a study by Zahran et al.91, extensive mycelial coverage was observed on the carcasses of Cimex hemipterus treated with T. harzianum, suggesting that the mechanism of pest control by T. harzianum may be parasitism. Saifullah and Khan75 conducted a detailed study on the infection process of Globodera rostochiensis by T. harzianum using low temperature scanning electron microscopy. They found that T. harzianum can infect mature cysts and egg masses through direct penetration of the cyst wall or via natural openings. Additionally, mycelial growth inside the cysts was observed, suggesting that T. harzianum may further disrupt the internal structure of nematodes after colonization. Contina et al.16 employed a green fluorescent protein-tagged T. harzianum strain to investigate its colonization of the oocysts and second-stage larvae (J2) of Globodera pallida, thereby corroborating its parasitic capabilities. This process relies on the synergistic action of chitinases, proteases, and lipases, where PR1 protease is responsible for surface adhesion, and other enzymes degrade the cuticle to facilitate invasion59. Szabó et al.79 examined the expression patterns of chitinase genes of T. harzianum (chi18-5 and chi18-12) during egg parasitism in Caenorhabditis elegans using real-time PCR. Their findings revealed that chi18-12 is induced earlier (1 hpi) with significantly higher expression, while chi18-5 is upregulated later (5 hpi) with lower expression, performing distinct functions at various stages of parasitism, thereby uncovering the specificity of gene regulation in the parasitic process.

Furthermore, during the spore germination stage, fungal spores may block insect spiracles, leading to high pest mortality64, providing new evidence for the physical interference mechanism.

Trichoderma harzianum produces insecticidal secondary metabolitesTrichoderma harzianum produces a diverse array of secondary metabolites with insecticidal properties, including both volatile and non-volatile compounds. In their study, Rahim68 demonstrated that mycelial extracts of T. harzianum exhibited significant insecticidal activity against Diuraphis noxia and Tribolium castaneum, with a lethality rate exceeding 70% at a concentration of 1000μg/ml within 24h, which was significantly higher than that of the blank control group. De Oliveira et al.22,23 reported that the treatment of Pratylenchus brachyurus with non-volatile compounds derived from T. harzianum resulted in a 65% mortality rate within 24h, comparable to the effect of the chemical pesticide abamectin, providing a new alternative for replacing highly toxic chemical insecticides. Further investigations into the molecular mechanisms revealed the upregulation of 1567 genes in P. brachyurus, notably including the 6-methyl salicylic acid decarboxylase gene and the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase gene. These genes play a critical role in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites and xenobiotic metabolism, potentially inhibiting the growth of P. brachyurus through the production of specific metabolites. Lana et al.49 studied the liquid culture filtrate of T. harzianum and found that rhizoferrin was detected only in the filtrate of T. harzianum co-cultured with cotton bollworm tissues, indicating that it may be a key metabolite responsible for insecticidal activity. Shakeri and Foster76 discovered that T. harzianum produced proteases and peptaibol antibiotics exhibiting high toxicity to Tenebrio molitor larvae. Component analysis using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and thin-layer chromatography revealed that these peptaibols were primarily composed of amino acids (e.g., proline and alanine), amino alcohols (e.g., leucinol and alaninol), and α-aminoisobutyric acid.

Antifeedant effect and insect-repellent effectSecondary metabolites produced by T. harzianum exhibit notable antifeedant and repellent properties. Ganassi et al.34 conducted a study to examine the feeding preferences of Schizaphis graminum on leaves immersed in a suspension of T. harzianum. Their findings indicated that the inhibitory effect of T. harzianum on the alate morphs of aphids was highly significant compared with the control group, and it also exerted a significant inhibitory effect on the apterous morphs at specific time points. Furthermore, Rodríguez-Gonzalez et al.69 demonstrated that the E20 strain of T. harzianum, developed through silencing of the erg1 gene, acted as a repellent to adult Acanthoscelides obtectus. This genetic modification resulted in reduced residence and feeding of A. obtectus on beans, while the T34 strain showed significant attractiveness to A. obtectus, leading adults to have more contact with treated beans. This difference in behavioral regulation reflects a contrast in bean protection mechanisms: E20 relies on repellency to reduce pest contact, whereas T34 enhances adult contact with spores through attractiveness to exert lethal effects. Binod et al.9 conducted an investigation in which cotton leaves treated with T. harzianum culture filtrate were administered to Helicoverpa armigera. The results indicated that the filtrate exhibited a significant antifeedant effect. Subsequent enzyme activity assays and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analyses revealed the presence of biologically active chitinase in the filtrate. This discovery implies that chitinase within the T. harzianum culture filtrate may serve as the principal bioactive component responsible for conferring resistance to H. armigera feeding on cotton. Furthermore, the volatile compound 6-pentyl-α-pyrone (6-PP), produced by T. harzianum in the maize root system, significantly reduced feeding on maize roots by Phyllophaga vetula, with the preservation rate of maize root biomass increasing from 65.5% to 75.8% compared with the control group18.

Indirect actionThe indirect effects of T. harzianum are diverse and complex, mainly encompassing enhancing plant intrinsic resistance, inducing plants to release volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that attract natural enemies, and interfering with insect-associated symbiotic fungi.

Induce and improve plant resistanceT. harzianum plays a significant role in inducing plants to enhance their resistance. It primarily enhances crop resistance mechanisms by augmenting crop nutrient content or facilitating the uptake of nutrient elements, as well as by inducing antioxidant enzymes in plants, thereby activating crop resistance mechanisms. At the level of nutritional fortification, Nafady et al.61 conducted a comprehensive study on tomato plants inoculated with T. harzianum to assess both nutrient content and the production of plant growth-promoting compounds. The study revealed that the levels of N, P, K, and Ca were significantly elevated in inoculated plants compared with uninoculated controls, thereby improving the growth vitality and stress resistance of the plants. As a beneficial microorganism, T. harzianum is also capable of inducing systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and induced systemic resistance (ISR) by stimulating defense-related enzymes and the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites32. Among these, salicylic acid (SA) is a key signaling molecule mediating SAR, while jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene co-regulate the initiation of ISR53. Yan et al.89 analyzed the contents of JA and SA in the roots of tomato plants inoculated with T. harzianum and found that their contents were significantly higher than those in nematode-infested plants, increasing by 32.66% and 18.07% respectively. Furthermore, Papantoniou et al.66 analyzed the expression levels of JA and SA pathways in tomato plants inoculated with T. harzianum via PCR. When attacked by Spodoptera exigua, the SA carboxyl methyltransferase gene was significantly upregulated, which in turn affected the synthesis and release of methyl salicylate (MeSA) and enhanced the attraction of natural enemies.

Elevated levels of reactive oxygen species in plants following pest attacks can induce oxidative stress, resulting in lipid peroxidation of cell membranes and electrolyte leakage, thereby posing several risks, including damage to plant tissues57,89. T. harzianum significantly upregulates the activities of enzymes such as polyphenol oxidase (PPO), peroxidase (POD), and phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), which are crucial for the accumulation of phenolics and the mitigation of oxidative stress during the enhancement of plant self-resistance22,46. Furthermore, these enzymes alleviate oxidative stress by catalyzing the conversion of phenolics to quinones and enhance plant defenses by reinforcing cell walls through lignin deposition, thereby reducing the plant digestibility to insects89.

Attracts natural enemies of pests and affects insect symbiotic fungiFurthermore, T. harzianum stimulates the production of VOCs in plants, thereby establishing a “plant-natural enemy-pest” tri-trophic regulatory network to achieve ecological regulation of pest populations11. Van Hee et al.85 demonstrated, through Y-tube olfactometer experiments, that T. harzianum significantly increased the attractiveness of Trissolcus basalis to post-oviposition plants of the sweet pepper nightshade moth. This effect was attributed to the induction of specific VOC emissions from the plants. Coppola et al.19 demonstrated that T. harzianum-treated tomato plants infested with Macrosiphum euphorbiae exhibited significantly enhanced emission of MeSA, Z-3-hexen-1-ol, and β-caryophyllene, which correlated with a 60.6% oriented flight response rate of Aphidius ervi parasitoids, representing a 2.67-fold increase compared with untreated controls (22.6%). These compounds increased the plant's appeal to the natural enemies of M. euphorbiae, thereby indirectly enhancing the tomato's defensive capabilities. The colonization by T. harzianum modifies the plant's capacity for the biosynthesis and emission of VOCs. Papantoniou et al.66 analyzed VOCs from T. harzianum inoculated tomato plants and found a marginal increase in the levels of the monoterpenes α-phellandrene and α-terpinene, which may attract natural enemy insects and thus enhance the indirect defense mechanisms of the plant. Notably, Contreras-Cornejo et al.18 revealed the dual defensive value of VOCs in their study on maize roots: α-pinene and β-caryophyllene, which are induced and released by T. harzianum, can not only directly recruit natural enemy insects, but also directly inhibit the proliferation of soil-borne pathogens, thereby achieving the synergistic enhancement of plant direct and indirect defenses.

Trichoderma harzianum employs a distinctive mode of action against beetles of the genus Xylosandrus, primarily disrupting the fungus-insect symbiosis to achieve indirect pest control. This mechanism not only impedes the proliferation of symbiotic fungi, but also indirectly influences the development of pest progeny through the modulation of symbiotic fungal growth36. For instance, in a study concerning Xylosandrus germanus, T. harzianum demonstrated efficacy in suppressing the growth of its symbiotic fungus, Ambrosiella grosmanniae, consequently diminishing the reproductive success and population size of X. germanus48.

Application of T. harzianum in pest controlNematode controlNematodes are a group of invertebrates belonging to Nematoda83. They are among the most abundant multicellular organisms on Earth, with a wide variety of species and forms. Widely found in soil, many of these species are important agricultural pests, such as Meloidogyne spp., Pratylenchus spp. and Globodera spp.22,24,75. They infest the plant root system and form root nodules that affect water and nutrient uptake, leading to the yellowing of leaves, poor growth and reduced yield62.

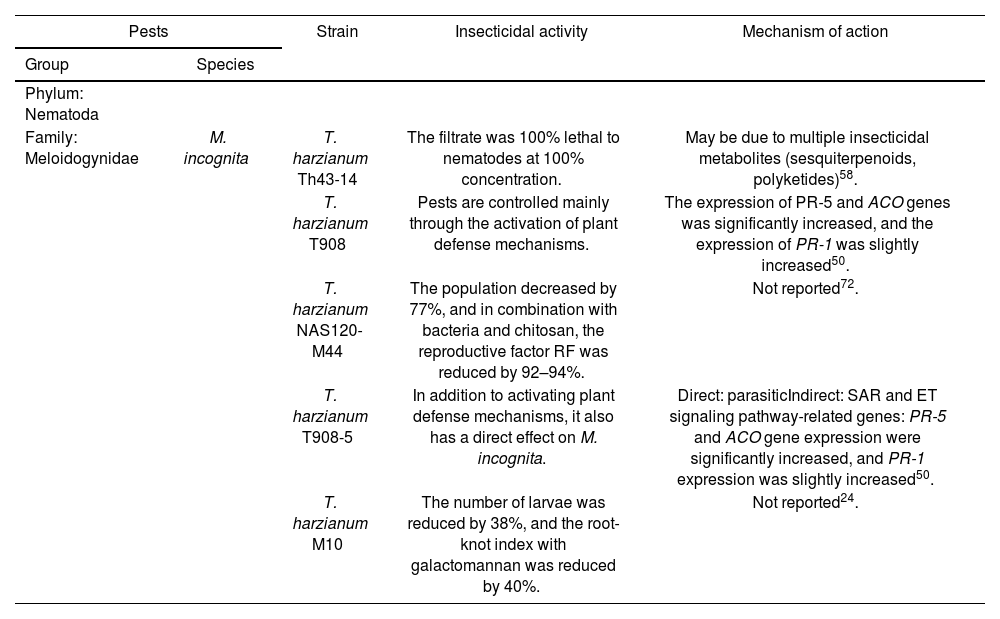

Trichoderma harzianum exhibits a robust capability to parasitize nematode eggs, primarily through the production of chitinase, which facilitates the degradation of nematode eggs and consequently reduces nematode reproduction. Szabó et al.80 demonstrated that the expression of various protease genes (e.g., pra1, p5216, etc.) in T. harzianum follows a specific pattern during the in vitro parasitization of Caenorhabditis elegans eggs, playing a crucial role in the parasitic process. Furthermore, Moo-Koh et al.58 reported that T. harzianum filtrate exhibited 100% lethality against Meloidogyne incognita at full concentration, demonstrating strong insecticidal efficacy. In contrast, under the same full concentration condition, Trichoderma citrinoviride showed a significantly lower performance, with only 62% lethality against the same pathogen. This marked difference in insecticidal activity is hypothesized to be linked to the production of diverse bioactive metabolites, such as sesquiterpenoids and polyketides, which may be more abundantly or effectively synthesized in T. harzianum.

The management of nematodes by T. harzianum also encompasses indirect pest control through the induction of plant defense mechanisms. Leonetti et al.50 detected tomato plants inoculated with T. harzianum and found that PR-1, PR-5, and ACO genes were overexpressed compared to the non-inoculated group, indicating that T. harzianum significantly enhances tomato resistance to M. incognita by activating plant SAR and ET signaling pathways. Current research on T. harzianum predominantly focuses on synergistic control strategies. Tiwari et al.81 demonstrated that the combination of T. harzianum with Bacillus subtilis and Priestia megaterium (formerly Bacillus megaterium) in sterile soil significantly reduced M. incognita infestation in Ocimum basilicum. These data indicate that the synergistic effect between different microorganisms can form a “functional complementarity”. The induced resistance of T. harzianum, combined with the potential antibacterial and lytic properties of Bacillus spp. significantly amplifies the control effect. Similarly, Dandurand and Knudsen21 observed that the integration of T. harzianum with Solanum sisymbriifolium significantly enhanced the control efficacy against G. pallida compared to treatments with T. harzianum alone or only potato planting.

Aphid controlAphids, belonging to the family Aphididae, are small sap-sucking insects whose modes of damage are primarily categorized into direct and indirect effects. Direct damage occurs when aphids extract plant sap, leading to nutrient depletion, inhibited growth, leaf curling, yellowing, and, in severe instances, wilting and plant death, thereby significantly impacting crop yield and quality34. Indirect damage, while more subtle, can have more severe consequences, as aphids serve as vectors for various plant viruses, facilitating the transmission of these pathogens and resulting in viral diseases30. Common species in the Aphididae family include Aphis gossypii, Schizaphis graminum, and Brevicoryne brassicae. The impact of aphids is not limited to direct growth inhibition and yield reduction; their role in virus transmission exacerbates their threat, making them a critical concern in agricultural production7,20,43.

As a significant biocontrol fungus, T. harzianum has demonstrated considerable potential for application in aphid management. Mukherjee et al.59 evaluated the biocontrol efficacy of T. harzianum against A. gossypii through both laboratory and field experiments. Their findings indicated that under controlled indoor conditions, 100% mortality of adult aphids was achieved within 72h. In field experiments, three consecutive applications of T. harzianum spore suspensions were found to be as effective as the chemical pesticide malathion.

Additionally, Coppola et al.20 reported that T. harzianum enhances the defense mechanisms of tomato plants against aphids (Macrosiphum euphorbiae). Transcriptomic analyses revealed an upregulation of defense-related genes, including ET-responsive transcription factors, PPO, and POD, in treated tomato plants. Metabolomics analysis revealed that T. harzianum contributes to the accumulation of isoprenoids, including sesquiterpenes, which offer direct defense mechanisms against aphids. Additionally, T. harzianum induces systemic resistance in tomato plants through the cross-regulation of JA and ET signaling pathways, thereby facilitating a rapid and effective response to aphid infestation.

Ganassi et al.34 studied the anti-feeding effects of various Trichoderma strains on S. graminum, revealing that T. harzianum significantly influenced the feeding preference of alate morphs, while its impact on apterous morphs was smaller. Pacheco et al.65 isolated T. harzianum and other fungal strains from marine environments and assessed their impact on the survival rates of B. brassicae. Their findings demonstrated that T. harzianum exhibited high lethality against B. brassicae, achieving up to 70% lethality within 72h.

Other insect and invertebrate pest controlBeyond its efficacy against nematodes and aphids, T. harzianum demonstrates effectiveness against a wide range of other insect and invertebrate pests, providing additional strategies and justification for its use in biological control. The filtrate and spore suspension of T. harzianum, when sprayed on pests, showed significant insecticidal effects against Earias insulana and Pectinophora gossypiella compared to the control group, with mechanisms involving parasitism and the production of insecticidal secondary metabolites27.

For Diatraea saccharalis, enzymatic extracts from T. harzianum act as “synergists” and increase insecticidal efficiency by 43.5% compared with the control group55. In the management of Sirex noctilio, T. harzianum indirectly impedes larval access to nutrients by inhibiting the growth of its symbiotic fungus, Amylostereum areolatum, thereby increasing larval mortality87.

The application of T. harzianum also extends beyond storage pests, effectively protecting mung bean seeds from Callosobruchus maculatus and Callosobruchus chinensis1. Other invertebrates, including spider mites (Tetranychus urticae), are controlled through the induction of plant defense genes and growth promotion37, while gastropods such as Monacha obstructa are susceptible to direct parasitism, with lethality increasing with spore concentration3. Collectively, these results highlight the broad-spectrum pest control capabilities of T. harzianum, supporting its versatile role in integrated pest management.

The species, efficacy, and mechanisms of action of T. harzianum for pest control are summarized in Table 1.

Trichoderma harzianum pest control species and their mechanisms of action.

| Pests | Strain | Insecticidal activity | Mechanism of action | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Species | |||

| Phylum: Nematoda | ||||

| Family: Meloidogynidae | M. incognita | T. harzianum Th43-14 | The filtrate was 100% lethal to nematodes at 100% concentration. | May be due to multiple insecticidal metabolites (sesquiterpenoids, polyketides)58. |

| T. harzianum T908 | Pests are controlled mainly through the activation of plant defense mechanisms. | The expression of PR-5 and ACO genes was significantly increased, and the expression of PR-1 was slightly increased50. | ||

| T. harzianum NAS120-M44 | The population decreased by 77%, and in combination with bacteria and chitosan, the reproductive factor RF was reduced by 92–94%. | Not reported72. | ||

| T. harzianum T908-5 | In addition to activating plant defense mechanisms, it also has a direct effect on M. incognita. | Direct: parasiticIndirect: SAR and ET signaling pathway-related genes: PR-5 and ACO gene expression were significantly increased, and PR-1 expression was slightly increased50. | ||

| T. harzianum M10 | The number of larvae was reduced by 38%, and the root-knot index with galactomannan was reduced by 40%. | Not reported24. | ||

| T. harzianum | When used synergistically with press mud, it not only promoted plant growth, improved plant resistance, but also effectively inhibited the reproduction and damage of nematodes63.Compared to the control group, the number of root galls and the nematode reproduction factor were reduced by 88.1% and 69.7%, respectively90.The egg hatch inhibition rate of M. incognita by T. harzianum was 77.6%, and the juvenile mortality rate was 82%84. | It significantly increased the activity of nitrate reductase and carbonic anhydrase in plants, which was conducive to nutrient absorption and metabolism in plants. The activity of antioxidant enzymes ascorbate peroxidase (APX), CAT, POD, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) was enhanced63. Induced synthesis of secondary metabolites (phenolics, flavonoids, and lignans, etc.) and enhanced plant cell wall strength; increased activity of defense-related enzymes (chitinase, β-1,3-glucanase, and protease, etc.)89.Insecticidal secondary metabolites81. | ||

| Meloidogyne hapla | T. harzianum IG03 | M. hapla lethality was 83.3% after 24h. | Direct effect62. | |

| M. javanica | T. harzianum Th20-07 | 97% mortality at 50% concentration of filtrate. | Insect parasitism of insects mediated by chitinases and proteases, etc58. | |

| T. harzianum | Reduced number of root nodules, number of egg masses and total nematode population. | Not reported73. | ||

| T. harzianum BI | Tomato seedling roots treated with different concentrations of suspension reduced the number of root knots and root blocks, and prolonged the incubation time of M. javanica, thus reducing nematode hatchability. | Parasitism; the activities of PAL, POX and PPO enzymes in tomato roots were enhanced, and systemic resistance was induced in plants74. | ||

| T. harzianum AUMC14897 | Compared with the control group, the number of J2, egg masses and root knots decreased by 55%, 43% and 52.38%, respectively. | The nutrient content of tomato plants was increased, and the activities of antioxidant enzymes catalase (GAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX) were enhanced, as well as plant resistance61. | ||

| T. harzianum MZ025966 | In terms of nutrient content, compared with the nematode-infected control group, the content was significantly increased61. | Indirect effect61. | ||

| Meloidogyne graminicola | T. harzianum | The filtrate inhibited egg hatching up to 37% and caused larval mortality by up to 71%, which demonstrates its insecticidal effect39. | Insecticidal metabolites39. | |

| Pratylenchidae | P. brachyurus | T. harzianum ALL42 | 65% lethality of metabolites to pests22. | Insecticidal metabolites; after being attacked by pests, they induce enhanced plant β-1,3-glucanase, chitinase, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, peroxidase activity22.Suppression of nematodes by secretion of multiple enzymes and secondary metabolites23. |

| Heteroderidae | G. pallida | T. harzianum | In combination with Solanum sisymbriifolium, the effect on nematodes is enhanced. | Not reported21. |

| T. harzianum ThzID1-M3 | Forty-five days after inoculation, the number of G. pallida decreased by 84%16. | T. harzianum not only colonizes the surface and endodermis of potato roots, but also infects the cysts and J2 of G. pallida, exerting lethal effects on the nematodes by directly penetrating their body surfaces16. | ||

| G. rostochiensis | T. harzianum | Fungal infestation was observed by the low temperature scanning electron microscopy technique. | Parasitism75. | |

| Rhabditidae | C. elegans | T. harzianum SZMC 1647 | Protease genes (e.g., p5216 and p9438) and chitinase genes (e.g., chi18-5 and chi18-12) are highly expressed during parasitism. | Parasitism80. |

| T. harzianum | The egg parasitic index ranges from 0.26 to 0.32, and compared with other Trichoderma spp., it has the strongest egg-parasitic ability. | Parasitism79. | ||

| Class: Insecta | ||||

| Order: Lepidoptera | ||||

| Family: Noctuidae | Spodoptera frugiperda | T. harzianum F2R41 | Significantly reduced the number of eggs and feeding rate of S. frugiperda. | Promote the growth of maize plants and induce antifeedant effects47. |

| Spodoptera littoralis | T. harzianum | When topically sprayed at a concentration of 108–1010spores/ml, larval mortality rate reached 43–50%. In addition, the filtrate could significantly inhibit larval weight gain. | Parasitism, metabolite-mediated insecticidal activity49. | |

| T. harzianum T24 | At a concentration of 1×108spores/ml, larval mortality rate is 80% | Parasitism28. | ||

| S. exigua | T. harzianum | Increased attraction to Macrolophus pygmaeus. | Release VOC to attract natural enemies: such as α-phellandrene, MeSA, etc66. | |

| H. armigera | T. harzianum | The filtrate containing chitinase can significantly reduce the feeding rate and weight gain of larvae, and affect their normal growth and development26. | Chitinase has an antifeedant effect9. | |

| Gelechiidae | T. absoluta | T. harzianum T39 | The number of larvae decreased by about 50% compared to the control group. | Promotes plant growth and induces plant defense gene expression (e.g., PR1a, PR1b, PI1, Pti5, and ERF1)37. |

| P. gossypiella | T. harzianum | Both the filtrate and the spore suspension had a significant insecticidal effect on pests. | Parasitic and insecticidal metabolites27. | |

| Nolidae | E. insulana | T. harzianum | Both the filtrate and the spore suspension had a significant insecticidal effect on pests. | Parasitic and insecticidal metabolites27. |

| Crambidae | D. saccharalis | T. harzianum Th180 | Improved insecticidal efficacy of enzyme extracts in combination with entomopathogenic fungi. | Enzyme extracts promote fungal parasitism39. |

| Order: Coleoptera | ||||

| Family: Chrysomelidae | Callosobruchus maculatus | T. harzianum | Combined application with inert dusts (diatomaceous earth and kaolin) resulted in 100% mortality after 7 days1. Alone, it was effective in suppressing progeny2. | Parasitism1,2. |

| Callosobruchus chinensis | T. harzianum | Combined application with inert dusts (diatomaceous earth and kaolin) resulted in 100% mortality after 7 days1. Alone, it was effective in suppressing progeny2. | Parasitism1,2. | |

| A. obtectus | T. harzianum T34 | When the T34 strain spores were directly sprayed on A. obtectus, adult mortality rate was 59.1% after 14 days71 and 68.8% after 15 days69. | Parasitic71. | |

| T. harzianum E20 | When the E20 strain spores were directly sprayed on adult A. obtectus, adult mortality rate reached 68.4% after 14 days71 and 81.7% after 15 days69. | Parasitic, with significant repellent effect69,71. | ||

| T. harzianum T109 | When the T019 strain spores were directly sprayed on adult A. obtectus, adult mortality rate reached 60.3% after 15 days42. | Parasitic69. | ||

| Thenebrionidae | T. molitor | T. harzianum 101645 and 206040 | Spore suspensions and mixtures of enzymes and peptide antibiotics had significant lethal effects on larvae. However, enzymes and antibiotics alone had no significant lethal effect. | Parasitism76. |

| T. castaneum | T. harzianum | Different media have different insecticidal effects on extracts. | Secondary metabolite pesticides68. | |

| Curculionidae | Xylosandrus compactus | T. harzianum T22 | Significantly reduced the number of beetles. | Inhibition of symbiotic fungal growth through antagonistic properties, thereby affecting the development of X. compactus progeny36. |

| Xylosandrus crassiusculus | T. harzianum | Symbiotic fungal growth is inhibited in beetle nests. | Influence progeny development by antagonizing symbiotic fungi13. | |

| X. germanus | T. harzianum | Significant inhibition of symbiotic fungal growth and reduction in eggs, larvae and pupae. | Indirectly affects beetle reproduction by inhibiting the growth of symbiotic fungi48. | |

| Cerambycidae | Xylotrechus arvicola | T. harzianum | Significant effect on eggs, larvae and adults. | Parasitism70. |

| Dermestidae | Trogoderma granarium | T. harzianum | With the increase of spore concentration, larval mortality rates reached 23.2%, 38.6% and 46.3% after 7, 14 days 21 days at 2.0×109spores/kg, respectively. | Direct action41. |

| Lampyridae | Pteroptyx bearni | T. harzianum | All 13 larvae were infected, achieving 100% larval mortality. | Parasitism31. |

| Scarabaeidae | P. vetula | T. harzianum | 6-pp can reduce pests feeding on corn roots. | The production of metabolites has an antifeedant effect18. |

| Order: Hemiptera | ||||

| Family: Pentatomidae | Nezara viridula | T. harzianum T22 | The direct effect had no significant effect on nymph mortality, and significantly reduced the relative growth rate of nymphs. In the T. harzianum-treated group, the residence time of parasitoids in plant volatiles was 38.4% longer than that in the control group85. | The expression levels of JA marker gene ToLO D and protease inhibitor gene ToPIN2 were significantly upregulated5. Enhances SA and JA-dependent defense gene expression86.Upregulating the expression of JA genes indirectly affects the release of plant volatiles85. |

| Aphididae | M. euphorbiae | T. harzianum T22 | Aphid survival was significantly reduced, and defense-related transcription factors were upregulated20. | Enhancement of inducible protease inhibitors and oxidative stress-related genes increases the release of volatile compounds and enhances the JA pathway20. |

| A. gossypii | T. harzianum T22 | The number of apterous aphids was significantly reduced compared with the control group32. | Approach and avoidance32. | |

| T. harzianum Amd1 | 100% aphid mortality was achieved within 72h at a concentration of 1×107spores/ml. | Parasitic, mainly dependent on chitinase, protease, and PR1 protein59. | ||

| S. graminum | T. harzianum ITEM908 and ITEM910 | It has a significant lethal effect. | Direct action35. | |

| T. harzianum | Significantly affected the feeding preference of winged aphids. | Secondary metabolites antifeedant effect34. | ||

| D. noxia | T. harzianum | Different media have different insecticidal effects on extracts. | Secondary metabolites are insecticidal68. | |

| Ceratovacuna lanigera | T. harzianum TMS623 | It has a high lethal potential for both nymphs and adults. | Parasitism45. | |

| B. brassicae | T. harzianum | The spore suspension has a significant lethal effect on B. brassicae. | Parasitism65. | |

| Aleyrodidae | B. tabaci | T. harzianum T39 | 35% reduction in pest count. | Promotes plant growth and induces plant defense gene expression (e.g., PR1a, PR1b, PI1, Pti5, and ERF1)37. |

| T. harzianum | Combined with SA or BABA, it has a significant insecticidal effect. | It enhanced the activity of defense enzymes and the accumulation of phenolic substances in plants, and significantly improved the resistance of tomato plants to B. tabaci46. | ||

| Trialeurodes vaporariorum | T. harzianum KF2R41 | It prolongs the development time of pests and significantly reduces the survival rate of adults and offspring. | Not reported67. | |

| Cimicidae | C.hemipterus | T. harzianum TM1 | The mean survival time decreased with increasing spore suspension concentration, and mortality increased from day 7 onwards. The mortality rate reached 90% on day 14 at a concentration of 1×104spores/ml. | Parasitism91. |

| Order: Hymenoptera | ||||

| Family: Siricidae | S. noctilio | T. harzianum | The larval mortality rate was 41.6%. | Inhibition of the growth of the symbiotic fungus A. areolatum indirectly affects the ability of larvae to obtain nutrients87. |

| Class: Arachnida | ||||

| Family: Tetranychidae | Tetranychus urticae | T. harzianum T39 | The number decreased by about 45% compared with the control group | Promotes plant growth and induces plant defense gene expression (e.g., PR1a, PR1b, PI1, Pti5, and ERF1)37. |

| Class: Gastropoda | ||||

| Family: Hygromiidae | Monacha obstructa | T. harzianum | Lethality increased with increasing concentrations | Parasitism3. |

Fungi used as natural biological control agents are prone to spore activity inhibition by environmental factors such as ultraviolet radiation, extreme temperature and humidity, which has long been a core bottleneck restricting their field efficacy54. To overcome this limitation, microencapsulation technology, relying on its physical barrier protection for active ingredients, has become a key technical means to improve the stability and activity of fungal spores, and relevant research has made a series of valuable advances.

At the technical application level, researchers have significantly improved the storage stability and environmental adaptability of fungal spores through diversified matrix selection and optimization of preparation processes. For example, Adzmi et al.4 innovatively used alginate and montmorillonite clay to construct a composite matrix for the microencapsulation of T. harzianum. Experimental results confirmed that this composite system can effectively buffer environmental stress, significantly improve the survival rate and structural stability of spores during storage, and provide a practical basis for the synergistic protection mechanism of multi-component matrices. Muñoz-Celaya et al.60 focused on spray drying, a process suitable for large-scale production, and systematically studied the impact of different carbohydrate polymer matrices on the activity of T. harzianum spores. They found that the mixed matrix of maltodextrin and gum arabic (MD10-GA) could minimize spore damage during the drying process. Not only did the survival rate after spray drying reach the highest level, but also 40% viability was maintained after 8 weeks of storage at 4°C, which was significantly better than that of unencapsulated spores. This finding provides key process parameter references for the industrial application of microencapsulation technology. The T. harzianum microcapsules prepared by Maruyama et al.54 using ion gelation not only constructed a physical protective barrier, but also significantly improved the activities of chitinase and cellulase through microenvironment regulation, providing a new mechanism for the enhancement of fungal biocontrol functions. In addition, Sundaravadivelan et al.78 synthesized silver nanoparticles using the filtrate of T. harzianum. This innovative method significantly enhanced the insecticidal effect against Aedes aegypti, opening up a new path for combining fungi with nanomaterials to improve biological control efficiency.

It is worth noting that polymer formulations also show good application prospects in nematode control. When galactomannan, as a polymer formulation, is used as a carrier for T. harzianum, it can not only effectively delay spore sedimentation to improve dispersion uniformity, but also form a continuous transparent film on the surface of plant roots, thereby significantly enhancing the control effect against nematodes. This provides diversified ideas for the formulation optimization of fungal preparations24.

Coordinated pest management approachesTrichoderma harzianum has demonstrated significant synergistic potential in the field of plant protection when used in combination with various biological or chemical substances. Through functional complementarity and mechanistic synergy, it not only broadens the spectrum of pest and disease control, but also promotes the diversified development of green pest management. The combined application of T. harzianum presents diverse technical pathways, covering the synergistic effects of substances from different sources.

In terms of combinations with plant-derived substances, Azeem et al.8 found that the combined use of Azadirachta indica extract and T. harzianum not only enhanced the inhibitory effect on M. incognita, but also achieved the dual efficacy of “pest control and growth promotion” by promoting tomato growth, reflecting the functional synergy between plant secondary metabolites and fungi.

In the field of microbial combinations, the synergistic application of T. harzianum with bacteria has achieved remarkable results. The co-application of P. megaterium and T. harzianum not only significantly reduced the infestation of M. incognita on O. basilicum, but also increased essential oil yield by improving plant physiological status, achieving the dual goals of pest control and enhancement of economic traits81. Additionally, combinations with entomopathogenic fungi enhance insecticidal efficacy through functional complementarity. For example, Mejía et al.55 combined crude chitinase extract from T. harzianum with entomopathogenic fungi, and the synergy between insect cuticle enzymatic hydrolysis and pathogenic infection significantly enhanced the lethal effect on D. saccharalis larvae.

With regard to combinations with chemical and physical agents, diversified technical solutions have been developed for pest control. Mendarte-Alquisira et al.56 studied the combined application of the commercial insecticide H24® (containing pyrethroids such as permethrin and allethrin, and carbamates such as propoxur) with Trichoderma spp., and found that T. harzianum can grow in an environment with a certain concentration of insecticides. This “compatible growth” trait lays the foundation for their synergy. The ternary combination of T. harzianum, diatomaceous earth, and spinosad achieved 100% mortality against adult C. maculatus and C. chinensis33. Through the multiple actions of physical damage (diatomaceous earth), chemical toxicity (spinosad), and fungal infection, it overcomes the limitation of insufficient control efficiency with a single method. Furthermore, the combination of T. harzianum with grain protectants such as inert dusts provides a low-residue solution for green insect prevention in storage environments1.

In the field of synergistic resistance enhancement with inducers, the combination of T. harzianum and chemical inducers provides a new approach for plant immune activation. Its combined use with SA or β-aminobutyric acid (BABA) significantly improves tomato resistance to Bemisia tabaci. The core mechanism is closely related to the enhanced activity of plant defense enzymes such as POD and PPO46, revealing the molecular basis of the synergistic activation of plant systemic resistance by fungi and chemical signal molecules.

Genetic engineering for enhanced biocontrolThe advancement of genetic engineering technology has provided potent tools for the modification of microorganisms, and T. harzianum, as a significant biocontrol agent, has garnered considerable attention due to its prominent potential in insecticidal activity and enhancing plant defense mechanisms. In recent years, research on the modification of T. harzianum through genetic engineering has continued to advance, further highlighting its core value in biological control.

With respect to enhancing insecticidal functions, multiple research results have been remarkable: Margolles-Clark et al.52 cloned the cbh1 promoter from Trichoderma reesei upstream of the endochitinase gene ech42 in T. harzianum, which increased the expression level of endochitinase in T. harzianum by 4–5 fold; chitinase is a key enzyme inhibiting pest population growth, and this modification directly enhanced the insecticidal potential of T. harzianum. Rostami et al.72 mutagenized T. harzianum using γ-rays, and the mortality rate of J2 stage nematodes reached 46%, which showed a significant improvement compared to the wild-type strain, effectively enhancing the antagonistic ability of T. harzianum against Meloidogyne javanica. In another study, strain E20, obtained by silencing the erg1 gene in T. harzianum T34, not only produced a significant lethal effect on A. obtectus adults, but also formed an avoidance effect on them, further expanding its application scenarios in insect control71.

In terms of regulating plant defense mechanisms, genetic engineering modification of T. harzianum also demonstrates positive potential. Eslahi et al.29 achieved overexpression of the chitinase gene (chit42) in T. harzianum through transgenesis; after plants were treated with this modified strain, the expression of defense-related genes (such as LOX1, PDF, and PR1) was significantly higher than in control plants. However, it should be noted that different modification strategies have varying impacts on plant defense genes: for example, Domínguez et al.25 studied the genetic engineering modification of T. harzianum T34 to express the acetamidase gene from Aspergillus nidulans. The results showed that this genetic modification significantly enhanced the growth-promoting effect of T. harzianum on tomato plants, improved the efficiency of plant nitrogen uptake and utilization, but unexpectedly inhibited the expression of plant defense genes. Nevertheless, this single case does not negate the core role of T. harzianum in enhancing plant defense. In fact, it naturally possesses the potential to stimulate plant defense responses, and the subsequent adoption of more precise gene-editing strategies is expected to further amplify its positive regulatory effect on plant defense mechanisms.

Conclusions and prospectsTrichoderma harzianum stands as a pivotal biocontrol resource in sustainable agricultural pest management, with its core role lying in its multifaceted “direct action-indirect regulation” mechanisms-including parasitism, insecticidal secondary metabolite production, and induction of plant resistance. These mechanisms enable the efficient control of nematodes, aphids, lepidopteran pests, and other invertebrates, while reducing reliance on chemical pesticides, aligning with the global urgency for green agricultural transformation. Its flexible application methods (e.g., seed treatment, soil drenching) and significant synergistic potential (when combined with microorganisms or plant-derived substances) have validated both economic and ecological value across crops such as tomatoes, corn, and soybeans. Future research and application must focus on strategic regional adaptation and technological breakthroughs, particularly addressing gaps in underrepresented regions like Latin America, to advance its transition from technical validation to large-scale implementation.

Latin America, a globally critical agricultural region renowned for producing corn, soybeans, coffee, and other crops, has long faced threats from transboundary pests such as root-knot nematodes and fall armyworms. Simultaneously, its rich tropical microbial diversity offers unique opportunities and challenges for the regionalized application of T. harzianum. Future research directions should concentrate on the following areas:

First, priority must be given to screening locally adapted, high-performance strains. To target dominant regional pests, strain resources should be explored from tropical rainforest soils and crop rhizosphere environments, with a focus on isolating T. harzianum strains tolerant to high-temperature and high-humidity conditions to enhance field control efficacy under real-world conditions.

Second, considering the local climatic characteristics of frequent rainy seasons and strong ultraviolet radiation, efforts should focus on optimizing microencapsulation technology and adopting materials such as degradable local polysaccharide matrices. These measures aim to address the issue of spore stability in hot and humid environments while reducing field application costs.

Third, to address the lag in biocontrol technology promotion in Latin America, a strengthened linkage between the “technology-policy-market” is essential. A multinational collaborative research network should be established to share application data, and unified registration standards for biocontrol agents should be developed. Concurrently, field demonstrations through a “research institution+cooperative+enterprise” model should be conducted to train farmers in low-cost application techniques.

These efforts will position T. harzianum as a multifunctional solution in key agricultural transformation regions such as Latin America, enabling chemical pesticide substitution, food security assurance, and ecological protection, and providing a replicable regional model for global sustainable agricultural development.

FundingThis work was supported by the Science and Technology Development Program Project of Jilin Province [grant numbers YDZJ202301ZYTS509].

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.