We present a case of multiple lymphangiohemangiomas (hematolymphangiomas, hemangiolymphangiomas, or combined lymphatic venous malformation) with thoracic and abdominal involvement in an asymptomatic patient. We describe and illustrate the imaging findings in this disease, which are quite characteristic and can enable an accurate diagnosis. To our knowledge, there are no other reports of similar cases in the scientific literature.

Presentamos un caso de linfangiohemangiomas múltiples (hemolinfangiomas, hemangiolinfangiomas o malformación vascular combinada linfática venosa) con afectación torácica y abdominal en un paciente asintomático. Describimos los hallazgos en imagen de esta patología, que son bastante característicos y pueden permitir un diagnóstico preciso. En nuestro conocimiento, no existen referencias en la literatura científica de un caso similar.

Lymphangiohaemangiomas, also known as haemolymphangiomas or haemangiolymphangiomas, are combined deformities of blood and lymphatic vessels.1–3 According to the ISSVA classification of vascular anomalies, they belong to the group of combined venous lymphatic vascular malformations.4

The aim of this article is to show the radiological findings in a patient with highly characteristic lymphangiohaemangiomas with thoracic and abdominal involvement, which facilitated an accurate diagnosis and avoided unnecessary surgery. The coincidence of thoracic and abdominal involvement in the same patient suggests that these are manifestations of the same disease.

Case reportThe patient was a 31-year-old man with no history of interest, referred to our department for the study of an incidental finding of a mediastinal mass on chest X-ray. The patient was asymptomatic, with no laboratory abnormalities.

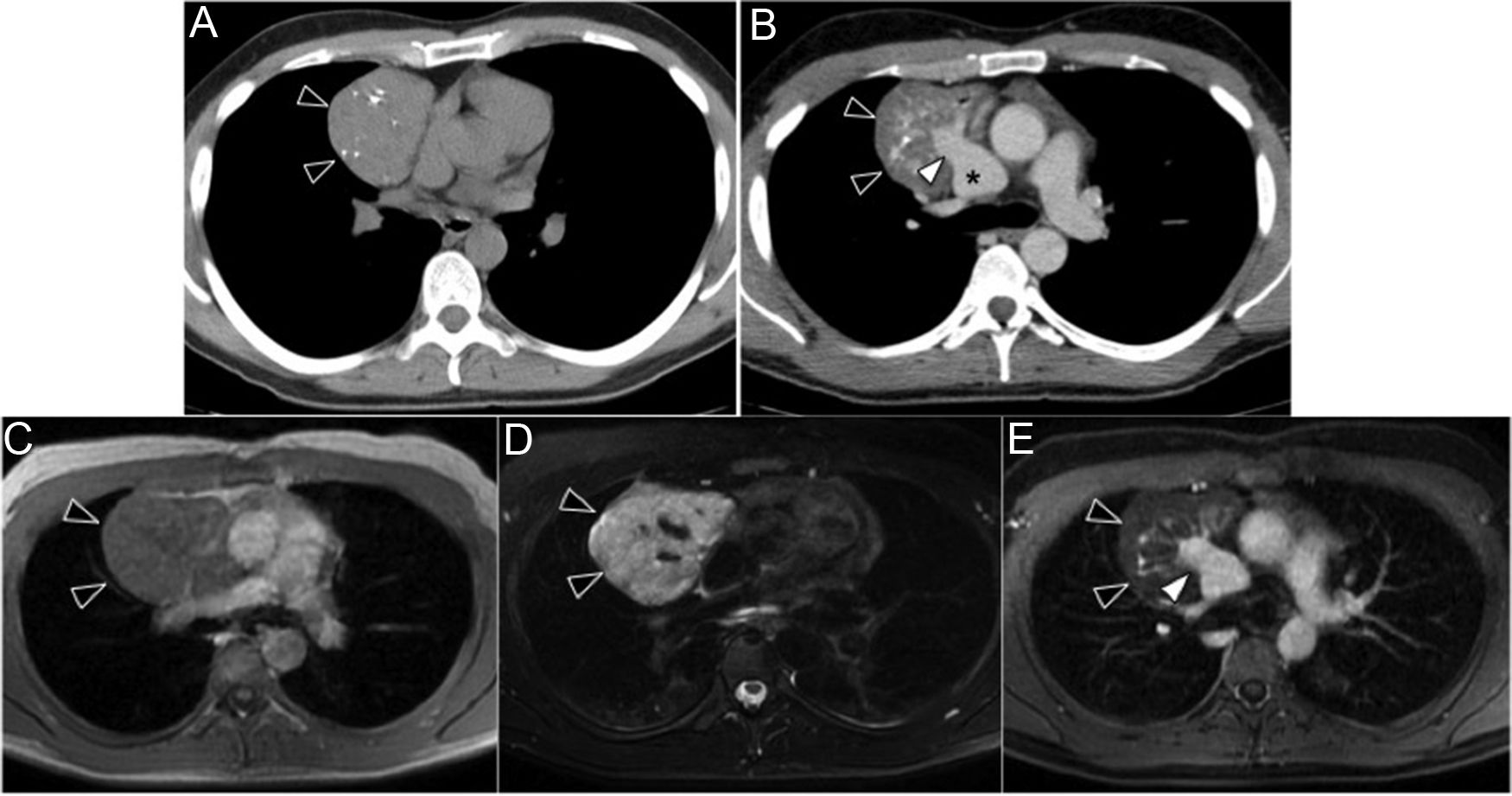

We performed computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, which showed a solid tumour in the anterior mediastinum, located in the right paracardiac region and surrounding, but not compressing, the superior vena cava. Several rounded calcifications, suggestive of phleboliths, were observed (Fig. 1A). Post-contrast images showed slight homogeneous enhancement, with multiple venous vessels that converged in a drainage vein leading to the superior vena cava, which was markedly dilated at this level (3cm diameter) (Fig. 1B).

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MRI) images of the thorax in the axial plane, showing the mediastinal mass (black arrowheads). (A) On CT without contrast, the mass is seen to contain multiple phleboliths. (B) After administration of contrast, slight enhancement of the thoracic mass is observed with multiple vascular structures in its interior that converge in a large drainage vein (white arrow) that leads to the dilated superior vena cava (asterisk). (C–E) On MRI, the mediastinal mass is slightly hypointense in the T1-weighted sequence (C), markedly hyperintense in T2 Fat-Sat FRFSE (D), and slightly enhanced in the LAVA T1-weighted gradient-echo sequence after the administration of intravenous gadolinium (E).

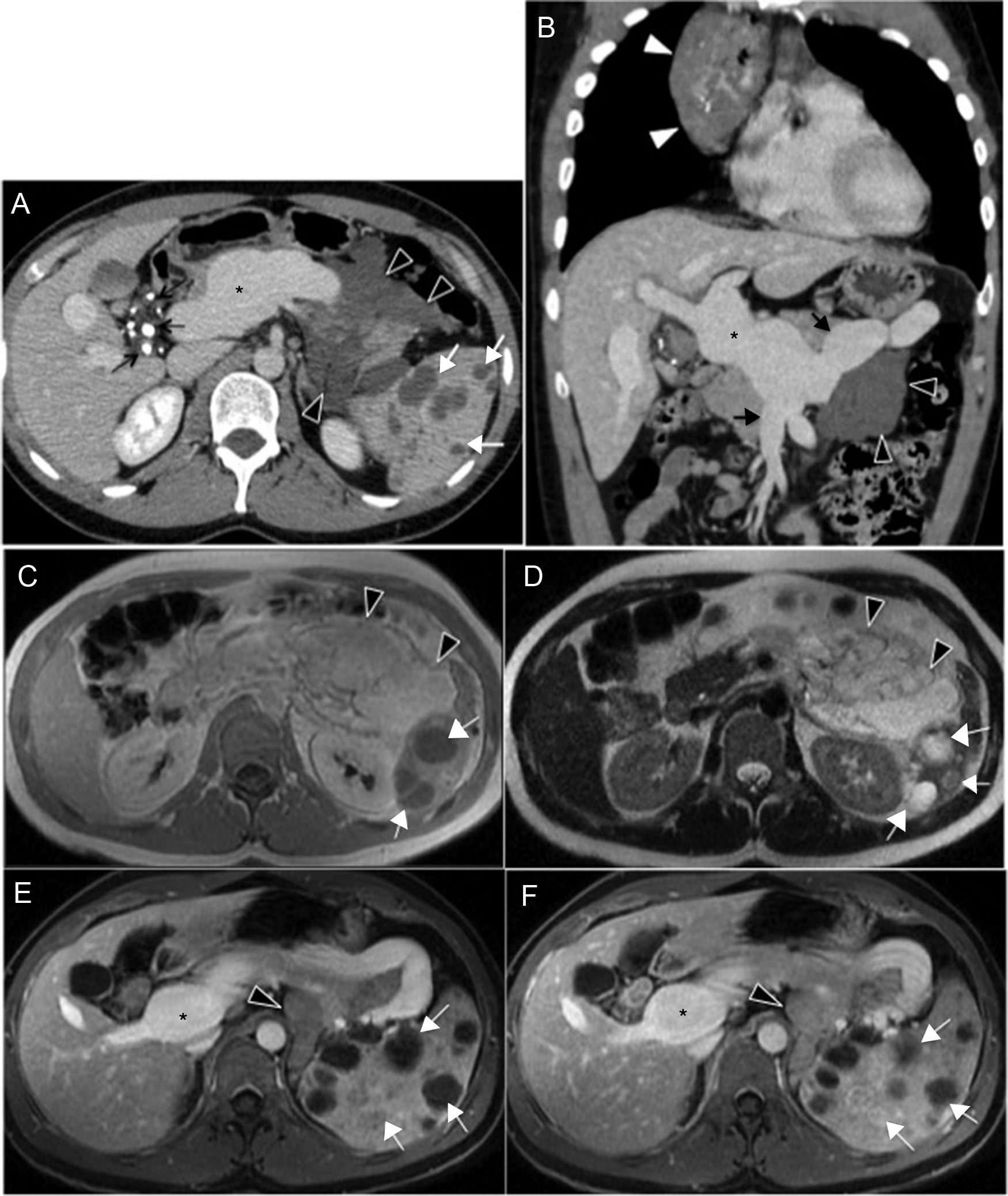

Another tumour composed of multiple mesenteric cysts extending towards the retroperitoneum was observed in the abdomen (Fig. 2A and B). Another small cluster of cystic lesions containing several phleboliths was identified between the gallbladder and the hepatic hilum (Fig. 2A).

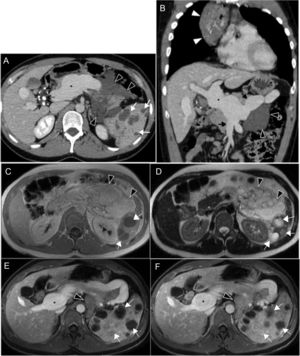

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MRI) images of the abdomen. (A) Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen in the portal phase, showing the mesenteric cystic lesions extending towards the retroperitoneum (black arrowheads) and notable dilation of the portal vein (asterisk). Multiple phleboliths with small cystic lesions in the hepatic hilum (black arrows). Numerous hypodense lesions in the spleen (white arrows). (B) Coronal reconstruction of chest and abdomen CT with iodinated contrast in the portal phase showing the mediastinal mass (white arrowheads) and mesenteric cystic lesions (black arrowheads), and significant dilation of the portal (asterisk), splenic and superior mesenteric veins (black arrowheads). (C–F) Abdominal MRI images showing moderately hyperintense mesenteric cystic lesions extending to the retroperitoneum (black arrowheads) in the T1-weighted sequence (C) and T2 SSFSE (D), and without enhancement in the LAVA T1-weighted gradient-echo sequence after administration of intravenous gadolinium in the portal (E) and late (F) phases. There is slight splenomegaly (E and F) with numerous lesions inside (white arrows) that present a signal intensity similar to fluid in the T1-weighted sequence (C) and T2 SSFSE (D), and a heterogeneous appearance after administration of intravenous contrast in portal (E) and late (F) phases. Note the absence of enhancement of most lesions, and progressive enhancement of some. Dilated portal vein (asterisk in E and F).

Significant diffuse dilatation of the splenic vein and the portal vein were evident, the latter with a diameter of 4.5cm (Fig. 2A and B).

Finally, the spleen was slightly enlarged and contained multiple focal, cyst-like lesions (Fig. 2A).

In the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study, the mediastinal mass showed intermediate intensity on T1-weighted sequences and hyperintensity on T2, with and without fat suppression. Post-contrast images showed slight uniform enhancement (Fig. 1C–E).

The lesions in the mesentery and retroperitoneum, adjacent to the gallbladder and in the hepatic hilum, were moderately hyperintense in T2- and T1-weighted sequences, with no post-contrast enhancement, suggesting proteinaceous cysts (Fig. 2C–F).

The splenic lesions showed a signal intensity similar to fluid in all sequences, suggestive of cysts; others were hyperintense in T1 and T2-weighted sequences, several of them with progressive enhancement after gadolinium administration (Fig. 2C–F).

On the basis of the aforementioned findings, our diagnosis was multiple lymphangiohaemangiomas with mediastinal and abdominal involvement. Radiological follow-up with MRI was performed, which showed no changes in the lesions. Two years after diagnosis, the patient remains asymptomatic.

DiscussionThis is an exceptional case since it shows multiple mediastinal and abdominal involvement, with lesions in the hepatic hilum, mesentery, retroperitoneum and spleen. There are no references in the literature to multiple thoracic and abdominal involvement.

Lymphangiohaemangiomas (haemolymphangiomas or haemangiolymphangiomas) are vascular anomalies that are classified by the ISSVA as combined venous lymphatic vascular malformations.4

After a literature review, we observed that this type of lesion is usually referred to as a lymphangiohaemangioma if it is located in the thorax,1,2,5–8 and as a haemolymphangioma9,10 or haemangiolymphangioma3 if it appears in the abdomen.

They are very rare in adults and only few cases have been reported.3 The most common sites are the lungs, the neck, the mediastinum and retroperitoneum.3

The symptoms depend on the site and size of the mass. Patients may be asymptomatic,1–3,5,7 but can also manifest symptoms that are nonspecific8 or secondary to compression of adjacent anatomical structures.6,9,10

The appearance of the lymphangiohaemangioma in imaging studies varies according to the size of the lymphatic and venous components.5,6

On CT, the lymphatic component shows a similar attenuation to water but occasionally may exhibit higher attenuation, indicating infection, haemorrhage or mucoid material.10 The venous components appear as serpiginous collections or structures separated by septa, and phleboliths,5 which manifest as calcified emboli in the venous canals, can be observed.2 Intense enhancement of intratumoural vascular spaces is observed post-contrast,8 indicating trapped contrast within the abnormal venous channels.6 In our patient, lesions in the hepatic hilum, mesentery and retroperitoneum were cystic in appearance. The thoracic mass was characteristic of a solid lesion with malformed vascular structures in its interior. Phleboliths were observed in both the chest and abdomen.

Other diagnostic options in the mediastinum include: thymoma, germinal tumour, treated lymphoma, calcified lymph node, haemangioma, primary intestinal cyst, neurogenic tumour, chronic venous thrombosis and calcified aneurysm.7

In the case of abdominal lesions, differential diagnosis should be carried out with lymphangiomas, enteric and mesothelial cysts, pseudomyxoma peritonei, benign cystic peritoneal mesothelioma, or non-pancreatic pseudocysts, among others.

The MRI findings of splenic haemolymphangiomas have not been previously reported in the literature. In our case, the spleen was slightly enlarged, with multiple cystic lesions on CT, that were heterogeneous on MRI. Differential diagnosis includes abscesses, cysts, lymphangiomas, haemangiomas, fibrosarcoma or metastatic tumours.9 Diagnosis was established based on the previously described findings in the thorax and abdomen.

Most published cases of mediastinal lymphangiohaemangiomas describe direct venous drainage into the superior vena cava or brachiocephalic vein.5 Superior vena cava ectasia, in the absence of indirect signs of obstruction, is believed to occur secondary to tumour-related dysplastic changes.8 Our patient presented significant dilation of the superior vena cava, which in our opinion was due to an increase in venous flow secondary to the malformation. Likewise, the portal and splenic veins were also greatly dilated, a finding that has not previously been reported in the literature in association with this entity. We believe this has a similar origin to superior vena cava ectasia in this case.

ConclusionWe presented a case of multiple lymphangiohaemangiomas with thoracic and abdominal involvement, which showed the characteristic radiological signs of this entity. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of its kind to be reported in the literature.

Although we have found these malformations referred to variously as lymphangiohaemangiomas, haemolymphangiomas and haemangiolymphangiomas, we believe that our case shows them to be different manifestations of the same entity.

We believe radiologists need to be aware of this pathology, since accurate radiological diagnosis is often possible and will negate the need for surgery, which is not indicated unless there are complications.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: García Roa MD, Ruiz Carazo E, Moya Sánchez E, López Milena G. Linfangiohemangiomas múltiples con afectación torácica y abdominal. Presentación de un caso. Radiología. 2019;61:85–89.