Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is an inflammatory disease of the central nervous system characterised by attacks of optic neuritis and longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. The discovery of anti–aquaporin-4 (anti-AQP4) antibodies and specific brain MRI findings as diagnostic biomarkers have enabled the recognition of a broader and more detailed clinical phenotype, known as neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD).

ObjectiveThis study aimed to determine the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with NMO/NMOSD with and without seropositivity for anti-AQP4 antibodies, in 2 quaternary-level hospitals in Bogotá.

MethodsOur study included patients > 18 years of age and diagnosed with NMO/NMOSD and for whom imaging and serology results were available, assessed between 2013 and 2017 at the neurology departments of hospitals providing highly complex care. Demographic, clinical, and imaging data were gathered and compared in patients with and without seropositivity for anti-AQP4 antibodies.

ResultsThe sample included 35 patients with NMO/NMOSD; the median age of onset was 46.5 years (P25-P75, 34.2-54.0); most patients had sensory (n = 25) and motor manifestations (n = 26), and a concomitant autoimmune disease was identified in 6. Twenty patients were seropositive for anti-AQP4 antibodies. Only age and presence of optic nerve involvement showed statistically significant differences between groups (P = .03).

ConclusionsClinical, imaging, and laboratory variables showed no major differences between patients with and without anti-AQP4 antibodies, with the exception of age of onset and presence of optic nerve involvement (uni- or bilateral); these factors should be studied in greater detail in larger populations.

La neuromielitis óptica es una enfermedad inflamatoria del sistema nervioso central, caracterizada por ataques de neuritis óptica y mielitis transversa longitudinalmente extensa. El descubrimiento del biomarcador diagnóstico anticuerpo anti-acuaporina-4 y los hallazgos imagenológicos en resonancia magnética cerebral han permitido el reconocimiento de un fenotipo clínico más amplio y detallado denominado espectro neuromielitis óptica.

ObjetivoDeterminar las características demográficas y clínicas de los pacientes diagnosticados con NMO/NMOSD, de acuerdo con la seropositividad del anticuerpo, en dos instituciones de cuarto nivel de complejidad en Bogotá.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio tipo serie de casos. Fueron incluidos aquellos pacientes > 18 años con diagnóstico de NMO/NMOSD, valorados en el Servicio de Neurología de dos hospitales de alta complejidad entre los años 2013 y 2017, con disponibilidad de estudios imagenológicos y resultados de serología. Se evaluaron variables demográficas, clínicas e imagenológicas, y se realizó un análisis de estas variables, según seropositividad del Ac-AQP4.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 35 pacientes con NMO/NMOSD, la mediana de edad de inicio fue de 46,5 años (P25-P75 = 34,2-54,0), la mayoría de los pacientes tuvo manifestaciones clínicas a nivel sensitivo (n = 25) y motor (n = 26), en seis (n = 6) pacientes se identificó una enfermedad autoinmune concomitante. Se encontró seropositividad en 20 pacientes. Encontramos algunas diferencias en las características clínicas e imagenológicas, pero solo la edad y el compromiso de nervio óptico mostraron diferencia estadísticamente significativa (p = 0,03).

ConclusionesNo se encontraron grandes diferencias clínicas, imagenológicas y de laboratorio, según la seropositividad del Ac-AQP4, excepto en la edad de inicio y el compromiso de nervio óptico (uni o bilateral), pero deben ser estudiadas de manera más detallada en poblaciones más amplias.

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is an idiopathic demyelinating inflammatory disease of the central nervous system (CNS) characterised by episodes of immune-mediated demyelination and axonal damage involving the optic nerve, spinal cord, and brain.1 It was first described in 1984 by Eugène Devic, who diagnosed a condition called “acute neuromyelitis optica” in a woman with paraplegia and bilateral vision loss with a fatal outcome.1,2 After this description, neuromyelitis optica (NMO) was considered a subtype of multiple sclerosis with more severe impairment of the optic nerve and the spinal cord. In 2004, the identification of antibodies targeting aquaporin-4 (AQP4-Ab), a CNS water channel, in patients with NMO enabled researchers to understand this condition as a disease with a different pathophysiological basis to that described in patients with multiple sclerosis, in which humoural immunity plays a fundamental role.3 The international consensus diagnostic criteria for NMOSD, based on the positive or negative test results for these antibodies, were published in 2015.4

The pathophysiology of AQP4-Ab–seropositive NMOSD is widely known; it is considered an immunoglobulin-G–mediated astrocytopathy that causes complement activation, leading to irreversible astrocyte loss through the formation of the membrane attack complex.5 However, the pathophysiology of AQP4-Ab–seronegative NMOSD is still under research; it has even been shown that 42% of seronegative patients are positive for anti–myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies.6 Previous studies have shown that, in some cases, the course of the disease may vary according to serostatus.7–10 Thus, seropositive patients tend to be younger and to present a higher degree of disability, although current studies report discrepancies in the clinical presentation, the course, and the severity of the disease, probably due to the limited number of epidemiological studies published.

Previous studies have shown different behaviour of NMOSD and different responses to a new immunomodulatory treatment (satralizumab),11 according to serostatus, leading to the hypothesis that the condition in seronegative patients is distinct to that of seropositive patients. The aim of this study is to analyse demographic, clinical, paraclinical, and prognostic characteristics according to serostatus, in order to determine whether seronegative and seropositive patients present distinct entities.

MethodsPatientsWe performed a retrospective, observational, case-series study to analyse data from 2 high-level hospitals in Bogotá (Colombia), between 2013 and the first quarter of 2019. We included patients aged 18 years and older, with a diagnosis of NMO, who attended the emergency department (new diagnoses or relapses in previously diagnosed patients) and met the international consensus diagnostic criteria for NMOSD, whose serostatus was known and who had undergone MRI studies at the admitting hospital.

We gathered data on demographic variables (sex, age of onset, and age at relapse), disease course (monophasic or polyphasic), topographical location of the lesion (spine, brainstem, optic nerve), symptom reported by the patient (sensory, motor, sphincter, vertigo, or visual symptoms [visual acuity impairment or diplopia]), anatomical lesion location in the MRI (spinal cord, diencephalon, brainstem, hemispheres, corpus callosum, optic nerve, or optic chiasm), degree of disability according to the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), the treatment received for the relapse, and the use of any disease-modifying treatment at the time of relapse. Clinical histories were reviewed by a neurologist and a final-year neurology resident.

MRI and paraclinical variablesMRI studies were performed with a 1.5 T scanner using T2-, T2-FLAIR, and T1-weighted sequences (with and without administration of contrast) with 3-5 mm thick slices. Contrast was dosed at 0.1 mmol/kg of bodyweight, with a minimum delay of 5 minutes and maximum delay of 13 minutes between contrast injection and acquisition of the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted sequence. MRI studies of the brain or the spinal cord were performed according to the symptoms and the findings of the neurological examination.

AQP4-Ab determination was performed by cell-based indirect immunofluorescence assay.

Statistical analysisThis study was presented to our hospital’s research committee; as this a retrospective, observational, non-interventional study, informed consent was not required. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical software, version 22. For the analysis of demographic, clinical, and imaging variables, results are expressed as absolute frequencies in the case of qualitative variables and medians and 25th and 75th percentiles for quantitative variables. We used the Mann–Whitney U test to compare quantitative variables and the chi-square test to compare qualitative variables in patients positive/negative for AQP4-Ab. P-values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

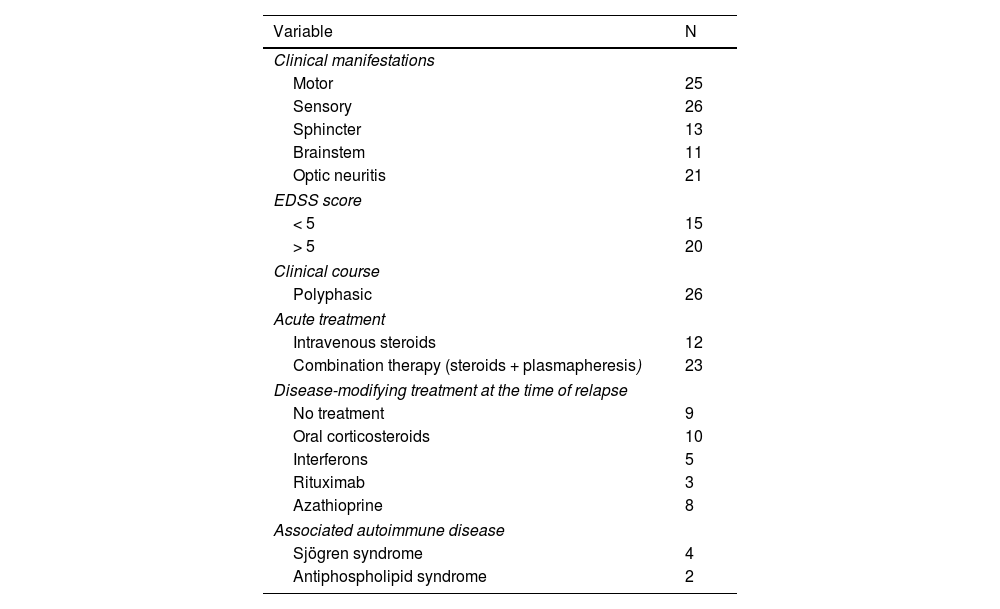

ResultsWe included 42 patients, 7 of whom were excluded due to incomplete data. Twenty-six patients were women, median age was 50 years (p25-p75: 28-56), and the median age at NMO/NMOSD onset was 46.5 years (34.2-54). All patients were of mixed race. Most patients presented sensory (n = 26) and motor (n = 25) clinical symptoms; 20 scored > 5 on the EDSS, and 6 presented a concomitant autoimmune disease. Of the 35 patients, 9 consulted due to a first episode. Table 1 summarises the clinical characteristics of our sample.

Clinical characteristics of the study population.

| Variable | N |

|---|---|

| Clinical manifestations | |

| Motor | 25 |

| Sensory | 26 |

| Sphincter | 13 |

| Brainstem | 11 |

| Optic neuritis | 21 |

| EDSS score | |

| < 5 | 15 |

| > 5 | 20 |

| Clinical course | |

| Polyphasic | 26 |

| Acute treatment | |

| Intravenous steroids | 12 |

| Combination therapy (steroids + plasmapheresis) | 23 |

| Disease-modifying treatment at the time of relapse | |

| No treatment | 9 |

| Oral corticosteroids | 10 |

| Interferons | 5 |

| Rituximab | 3 |

| Azathioprine | 8 |

| Associated autoimmune disease | |

| Sjögren syndrome | 4 |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | 2 |

EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale.

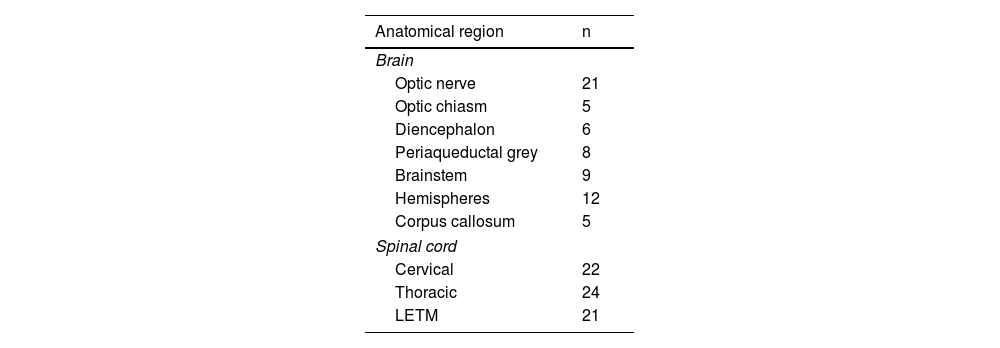

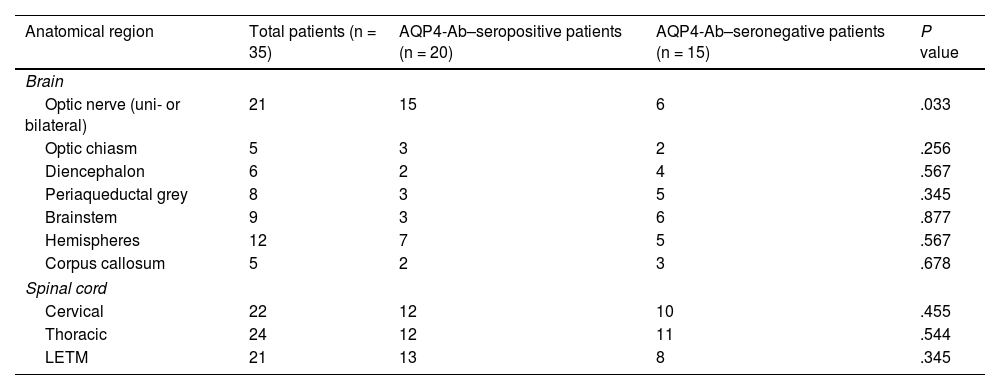

According to the findings of brain and cervical and thoracic spinal MRI studies, the most frequently affected region was the spinal cord, both at the cervical and thoracic levels. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) was observed in 21 patients. Table 2 describes MRI lesion characteristics according to their location.

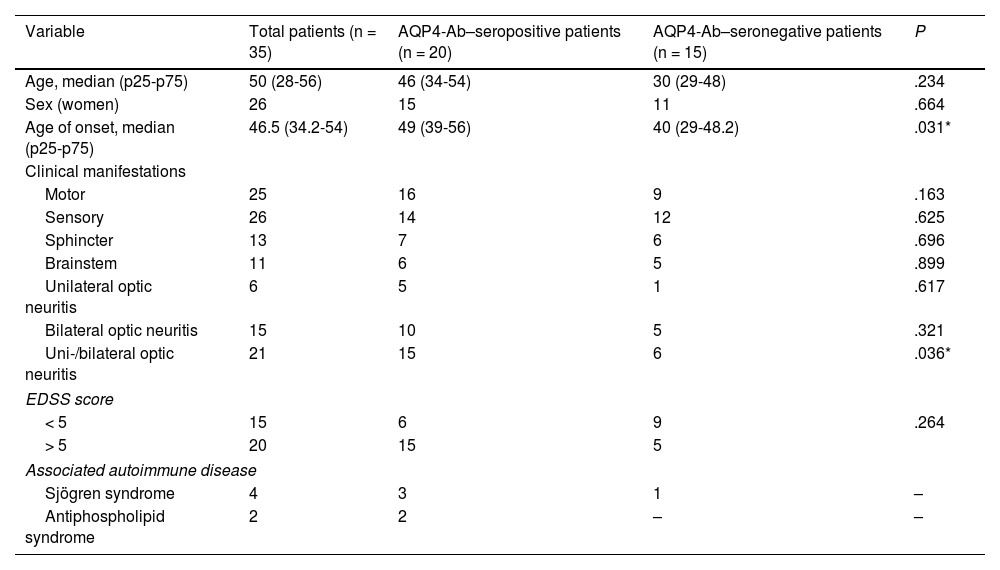

Twenty patients were seropositive for AQP4-Ab. Table 3 presents the distribution of demographic and clinical variables according to serological findings. It is noteworthy that the median age at onset of NMO/NMOSD was higher in AQP4-Ab–seropositive patients (49 years, p25-p75: 39-56) than in seronegative patients (40 years, 29-48.2) and that the majority of motor manifestations were observed in AQP4-Ab–seropositive patients (16 vs 9 in seronegative patients) (Table 3). No statistically significant differences were found in demographic and clinical variables between AQP4-Ab–seropositive and seronegative patients, except for the older median age (P = .03) and higher prevalence of optic nerve involvement in seropositive patients (P = .036).

Distribution of demographic and clinical variables, according to AQP4-Ab serostatus.

| Variable | Total patients (n = 35) | AQP4-Ab–seropositive patients (n = 20) | AQP4-Ab–seronegative patients (n = 15) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (p25-p75) | 50 (28-56) | 46 (34-54) | 30 (29-48) | .234 |

| Sex (women) | 26 | 15 | 11 | .664 |

| Age of onset, median (p25-p75) | 46.5 (34.2-54) | 49 (39-56) | 40 (29-48.2) | .031* |

| Clinical manifestations | ||||

| Motor | 25 | 16 | 9 | .163 |

| Sensory | 26 | 14 | 12 | .625 |

| Sphincter | 13 | 7 | 6 | .696 |

| Brainstem | 11 | 6 | 5 | .899 |

| Unilateral optic neuritis | 6 | 5 | 1 | .617 |

| Bilateral optic neuritis | 15 | 10 | 5 | .321 |

| Uni-/bilateral optic neuritis | 21 | 15 | 6 | .036* |

| EDSS score | ||||

| < 5 | 15 | 6 | 9 | .264 |

| > 5 | 20 | 15 | 5 | |

| Associated autoimmune disease | ||||

| Sjögren syndrome | 4 | 3 | 1 | – |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | 2 | 2 | – | – |

AQP4-Ab: anti–aquaporin-4 antibodies; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale.

Regarding brain and cervical and thoracic spinal MRI findings, lesions were distributed similarly in AQP4-Ab–seropositive and seronegative patients; the main difference in brain MRI studies was the prevalence of optic nerve injuries, which were more frequent in seropositive patients (n = 15) than in seronegative patients (n = 6). Table 4 shows the anatomical distribution of MRI findings according to AQP4-Ab serology results.

Distribution of imaging findings, according to AQP4-Ab serostatus.

| Anatomical region | Total patients (n = 35) | AQP4-Ab–seropositive patients (n = 20) | AQP4-Ab–seronegative patients (n = 15) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain | ||||

| Optic nerve (uni- or bilateral) | 21 | 15 | 6 | .033 |

| Optic chiasm | 5 | 3 | 2 | .256 |

| Diencephalon | 6 | 2 | 4 | .567 |

| Periaqueductal grey | 8 | 3 | 5 | .345 |

| Brainstem | 9 | 3 | 6 | .877 |

| Hemispheres | 12 | 7 | 5 | .567 |

| Corpus callosum | 5 | 2 | 3 | .678 |

| Spinal cord | ||||

| Cervical | 22 | 12 | 10 | .455 |

| Thoracic | 24 | 12 | 11 | .544 |

| LETM | 21 | 13 | 8 | .345 |

AQP4-Ab: anti–aquaporin-4 antibodies; LETM: longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis.

Lastly, laboratory results detected monoclonal bands in 2 patients, and the CSF analysis revealed predominantly lymphocytic pleocytosis in 4 cases and predominantly monocytic pleocytosis in 2, with median protein levels of 45 mg/dL (32-76) and median glucose levels of 59.5 mg/dL (47-72.5).

DiscussionFew studies have addressed the clinical manifestations of NMO and NMOSD.12 Worldwide prevalence of these disorders is variable, with large disparities between the estimations available to date; the local prevalence of the disease remains unknown.13,14 Our study contributes data at the local and regional levels, detailing the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with NMO/NMOSD attended at 2 reference centres in Bogotá (Colombia).

The main aim of our study was to expand our knowledge on the course of NMO and NMOSD and the clinical and paraclinical characteristics of patients, using the 2015 international consensus diagnostic criteria for NMOSD.12,15 NMO is an antibody-mediated inflammatory disease affecting the CNS, preferentially the optic nerves and spinal cord,2,16,17 as shown by our study, which revealed a high frequency of optic nerve involvement (n = 21) as compared to the other regions analysed in the MRI study.

We included a total of 35 patients who met the selection criteria; this sample size is similar to those reported in previous case series.2,12,18 Our patients presented a median age of onset of 46.5 years (p25-p75: 34.2-54) whereas previous studies have reported symptom onset at approximately 39 years of age,2,17,19 which may suggest that the age of symptom onset was older in our study population. Our findings are consistent with those of other authors, who report that symptom onset occurs later in patients with NMO than in patients with multiple sclerosis, with the latter presenting an age of onset between 20 and 40 years.17

The presence of AQP4-Ab in patients with NMO is associated with faster progression and more severe disability, which may lead to a higher mortality rate.20 Seropositive results for AQP4-Ab were observed in 20 patients, 15 of whom were women. Previous studies have reported that AQP4-Ab–seropositive women present more severe disability and more frequent association with other autoimmune diseases.9,12,19,21 In our study, we found greater disability among AQP4-Ab–seropositive patients.

A multi-centre study conducted in France, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom reported a high frequency of brainstem symptoms including vomiting and hiccups in non-white patients with NMO.22 In our study, the most frequent clinical manifestations were spinal symptoms (sensory [n = 25] and motor [n = 26]), followed by bilateral optic nerve symptoms (n = 15). We observed no clinical manifestations of area postrema syndrome or diencephalic syndrome; this finding is consistent with the data reported by the first local study performed in the city of Bogotá.12

Previous studies have analysed the presence of concomitant autoimmune diseases; however, in our study, we only observed 6 cases of autoimmune diseases: 4 cases of Sjögren syndrome and 2 of antiphospholipid syndrome. These figures coincide with previous reports23; for instance, the study by Reyes et al.,12 also performed in Colombia, found no associated autoimmune conditions. However, Reyes et al.12 did obtain positive results for antinuclear antibodies (a frequent finding in patients with NMO) in patients not meeting criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus, as well as the presence of anti-DNA antibodies, ANCAs, and anti-Ro antibodies; these findings were obtained in immunological tests of patients not meeting the diagnostic criteria for autoimmune inflammatory diseases.

A multi-centre study performed in France, Germany, Turkey, and the United Kingdom observed an association between late age of disease onset in AQP4-Ab–seropositive patients and a high risk of motor disability. In patients with late onset (≥ 50 years), the prevalence of LETM was 66%, compared to 28% for optic neuritis.24,25 In our study population, most AQP4-Ab–seropositive patients with NMO were older than 50 years, and presented spinal cord lesions and LETM.

We identified some differences between groups in clinical and imaging characteristics, but only age and optic nerve involvement showed statistically significant differences (P = .03).

The main strengths of our study are the combination of data of patients from 2 reference centres in the city of Bogotá (Colombia); the reporting of demographic, clinical, and imaging data of great relevance; and the analysis of results according to AQP4-Ab serology results. The main limitations are related to the retrospective nature of data collection, which resulted in missing data in some clinical records, and occasionally a lack of diagnostic clarity, which led to the exclusion of some eligible patients from the database. Information and measurement bias were avoided by cross-analysing the clinical records and, when possible, reviewing laboratory and imaging findings at both centres.

A larger sample of patients would be needed to analyse whether serostatus enables us to classify this condition as 2 distinct entities. The group of seronegative patients must undergo testing for other antibodies (anti–aquaporin 1 and 9, anti–myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies), and even repeat the test for AQP4-Ab if it was performed after starting immunosuppression or using a technique other than cell-based analysis (microscopy or flow cytometry).

ConclusionAQP4-Ab seropositivity in patients with NMO/NMOSD seems to be related to specific clinical, imaging, and analytical characteristics. In our study, we found statistically significant differences in age of onset and prevalence of optic nerve involvement (uni- or bilaterally), which should be further studied in larger population samples.

FundingThis study received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.