Convexity subarachnoid haemorrhage (cSAH) is characterised by the collection of blood in one or several adjacent sulci, without bleeding in the brain parenchyma, interhemispheric fissure, subarachnoid cisterns, or ventricles.1–3 The condition has been associated with numerous aetiologies, including trauma, aneurysms, cortical vein thrombosis, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS), cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), primary central nervous system vasculitis, coagulation disorders, cocaine or ethanol consumption, brain abscesses, cavernomas, or arteriovenous malformations (AVM).1–4 We present the case of a patient with cSAH secondary to hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT).

The patient was a 47-year-old man with history of recurrent epistaxis since childhood and family history of epistaxis: his mother and maternal uncle and grandfather had all undergone cauterisation of telangiectasias in the nasal cavity. He reported a 5-month history of oppressive left frontal headache of increasing intensity and frequency, eventually occurring daily. Pain was exacerbated by the Valsalva manoeuvre and was associated with vertigo, vomiting, and occasional photopsia. The patient did not report pain, consumption of vasoactive substances, or excessive alcohol consumption. Despite administration of intravenous dexketoprofen (50mg/8h), oral tramadol/paracetamol (37.5/325mg/8h), and oral prednisone (60mg/24h), he required rescue doses of subcutaneous morphine chloride (5mg).

Systemic examination revealed cutaneous angioma in the nasal apex and cherry angiomas on the tongue and lower lip; neurological examination revealed no abnormalities.

A coagulation test, a complete blood count, and blood biochemistry tests returned normal results. Cerebrospinal fluid composition and pressure were normal, with no erythrocytes. Exome sequencing revealed a novel missense mutation (c.236G>A; p.[Gly79Glu]) in exon 3 of the ACVRL1 gene on chromosome 12, which encodes activin A receptor-like type II-1.

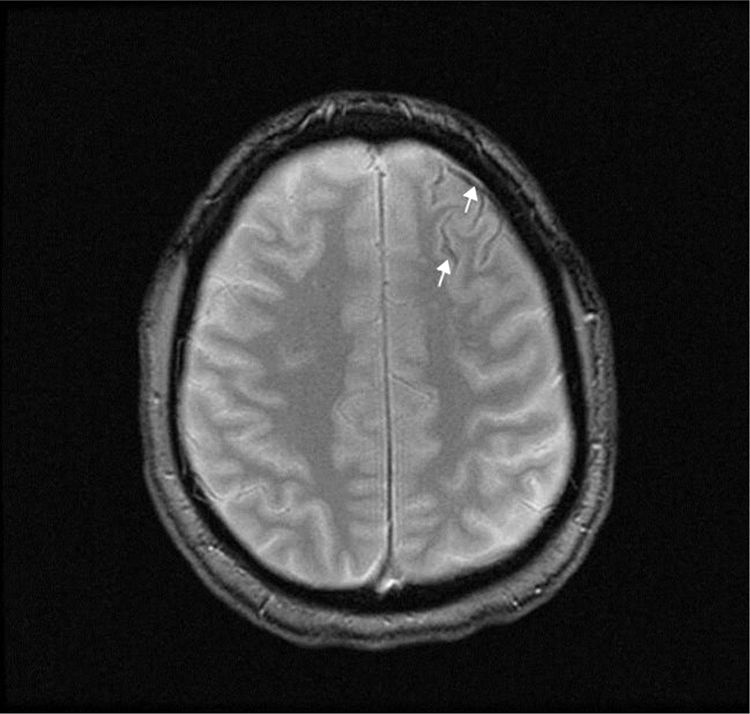

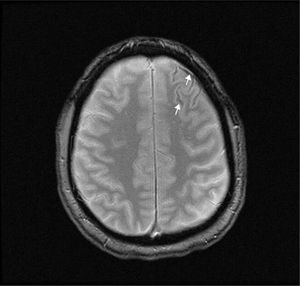

A T2-weighted brain MRI scan showed a thin line of magnetic susceptibility artefacts bordering the left frontal sulci, compatible with haemosiderin deposition (Fig. 1). We found no pathological gadolinium enhancement and no evidence of inflammation of the vascular walls. A transcranial duplex ultrasound study and a brain angiography yielded normal results. A rhinoscopy study identified telangiectasias in the nasal septum and conchae; these were cauterised.

HHT, also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, is a hereditary disease following an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern; prevalence is estimated at one case per 5000-8000 population.5–7 It most frequently manifests as epistaxis, with mucocutaneous telangiectasia being the most common sign.

The condition is diagnosed clinically according to the Curaçao criteria,8 which are based on the presence of: 1) recurrent spontaneous epistaxis; 2) multiple mucocutaneous telangiectasias in characteristic locations (lips, tongue, oral mucosa, and fingertips); 3) organ involvement (gastrointestinal system, lungs, liver, or brain9); and 4) a first-degree relative with HHT. Definitive diagnosis of HHT is established when at least 3 criteria are met.8

Genetic studies are recommended in the event of diagnostic suspicion or in the absence of family history of the condition.9 In our case, the patient met all 4 clinical criteria for HHT and also presented a genetic variant in the ACVRL1 gene; pathogenic mutations in this gene have often been associated with HHT.10

HHT can cause numerous neurological symptoms, including cerebrovascular malformations, abscesses, ischaemic stroke, seizures, and migraine. Ten percent of patients present multiple silent, low-flow AVMs, which can cause devastating haemorrhages.10–12 Other cerebrovascular malformations include capillary telangiectasias, developmental venous anomalies, arteriovenous fistulae, and saccular aneurysms.13 Thirty percent of patients with pulmonary AVMs present ischaemic stroke due to paradoxical embolism.14

The aetiology of cSAH varies according to patient age: in patients younger than 60 years, the most common cause is RCVS, whereas CAA is more common in those older than 60.1–4 Symptoms also vary according to age: thunderclap headache is the most common symptom in patients aged under 60, with transient focal episodes known as “amyloid spells” being more common in older patients.1–3 These episodes may be caused by a mechanism of cortical spreading depression (similar to that which occurs in migraine) due to the presence of blood in the cerebral cortex.3 Brain CT without contrast is the most immediate diagnostic test; however, due to its limited sensitivity, a brain MRI study is also required for diagnosis.15 In our patient, the MRI study revealed haemosiderin deposits in the anterior frontal cortical sulci, suggesting previous bleeding compatible with cSAH; despite this, angiography findings were normal. The bleeding was probably caused by a vascular malformation that was not visible in imaging studies due to rupture, small size, low flow rate, or vasospasm.

In summary, we present a case of cSAH secondary to HHT, an association not previously described in the literature. The identification of a novel variant in the ACVRL1 gene is also an interesting finding, whose pathogenic relevance should be assessed in family segregation studies.

Please cite this article as: Sancho Saldaña A, Lambea Gil Á, Sánchez Marín B, Gazulla J. Hemorragia subaracnoidea de la convexidad cerebral causada por telangiectasia hereditaria hemorrágica. Neurología. 2020;35:432–433.