The number of social network users is rising meteorically, a trend that also includes health-care workers. Even though social networking can serve educational functions and is an effective means of communicating medical resources, it is associated with a variety of important challenges. Misuse of social networks by health-care workers can have dire consequences, ranging from seemingly simple issues such as affecting the doctor's reputation to serious legal matters. Maintaining professionalism and preserving the concepts of confidentiality and privacy is essential. In this review we will analyze some of the dilemmas that have been brought about by the use of social networks in the healthcare environment, as well as existing guidelines on the matter.

The use of electronic information tools, including the use of social networks (SNs), have led doctors to reconsider how to apply the code of ethics that govern the doctor–patient relationship and maintain their professional behavior. Even though these mediums present interesting possibilities of beneficial interactions, they also bring with them different ethical and professional dilemmas. Some of the main challenges we face when using these technologies are the preservation of confidentiality and privacy and maintaining the boundaries of the doctor–patient relationship, as well as reducing the possibility of making public information which may be unprofessional, improper and even illegal.1,2

There are many SNs, among which the most popular are Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn (Table 1). Together this group of technologies has been defined as “Web 2.0”.1,2 In recent years, the rise in popularity and use of said SNs has been exponential. Up to June 2014, Facebook reported 1.32 billion monthly users.3 In this review, a summary of the available information on the impact of SNs on modern medical practice will be made, highlighting the ethical complexities that these may involve.

Health 2.0“Health 2.0” is a new concept which comprises the use of technology to promote and facilitate the interaction between healthcare providers and patients.

It includes the search for information, medical advances, updates and education in the field of healthcare.4 Even though this definition is not universally accepted, the concept appears in different scientific publications, and the impact that this will have on the evolution of healthcare services has not yet been fully established.5

The use of SNs can bring benefits to the institutions in charge of healthcare as well as the patients and the clinicians. The institutions may use them as publicity, customer service, and patient education; on the other hand, the patients can use SNs to obtain information, evaluate their progress and receive support. Finally, clinicians can obtain updated information, providing facilities in the research area a fast means of communication between colleagues in order to comment on complicated cases.6

In a meta-analysis of the literature on the use of SNs by patients, results showed that almost 30% of then use some kind of SN or “blog” related to their disease.7 In the majority of cases, the intention of this conduct was to educate themselves on topics related to self-care. In fact, it has been determined that there are 757 pages of SNs dedicated to groups of patients with specific diseases. Some of the most prevalent, according to the International Classification of Diseases 10, have over 300,000 users.8

Use of social networks: benefits and challengesNowadays SNs are considered a useful tool for medical teaching and practice.9 Although using it brings benefits like facilitating information to patients, a quick communication channel between the doctor and the patient and the establishment of national and international professional networks, it also confronts us with different challenges like preserving confidentiality, privacy, maintaining the boundaries in the doctor–patient relationship and maintaining professional behavior (in Table 2 there is a list of some areas where SNs present dangers in the medical practice).

Some of the potential dangers of the use of SNs by doctors.

| • Loss of confidence in the doctor–patient relationship. |

| • Divulgence of the patients’ confidential information, which may be punishable by law. |

| • Publication of improper material which brings into doubt the professionalism and prestige of the doctor or institution where one works. |

| • Association with false information or fraudulent treatments. |

| • Disappearance of the distinction between professional and social behavior, public and private, in the life of the doctor. |

Even though there are some cases where online “surveillance” of the current state of the patient has had beneficial results (notably in suicide watch cases, or a monitoring of neurological symptoms after a cerebral concussion), these are anecdotal, and in everyday practice electronic doctor–patient interactions bring more complications than benefits most of the time.10,11

- (a)

Confidentiality

One of the basic principles in the doctor–patient relationship is confidentiality. However, it is difficult to maintain in the context of electronic registries. The retention period of these registries may be undetermined and access may not always be restricted.

The most common examples where the use of SNs comes to violate medical confidentiality include cases where images, where there is the possibility of identifying the patient because of specific characteristics, are made public, either by showing his/her face, some part of his/her body or objects marked with the logo of a specific institution.12,13 Some experts consider that even when all information which may lead to the recognition of the patient is removed, there is still the possibility that someone may recognize them through context. Therefore, discussing clinical cases in an open forum should be avoided.

The use of expressions or improper language in the context of the publication of said images has even led to the termination of the doctors responsible. On this point, it is important to clarify that in some countries the existing medical–legal guidelines regarding medical confidentiality also apply to information disclosed online, and the violations of this class are subject to disciplinary and/or legal action.

- (b)

Privacy

The use of social networks has provoked a diffusing of the fine line between the private and professional life of the healthcare worker. It is recommended to regularly check the privacy configuration of our profiles. However, the use of the highest standards of privacy does not guarantee that the published content will continue to be private and confidential, or that any person will not be capable of accessing the published information. Once the information is published online, it may be difficult to eliminate.

There are many other instances where the use of SNs by health professionals can lead to situations which violate the privacy of the patients.

Beneficence is the concept that the doctor always tries to do good for the patients. In psychiatry, there are cases where a therapist has obtained information about the patient through his/her SN pages with the purpose of making a better alliance and therapeutic plan (i.e. regarding a traumatic background). Nevertheless, the patient found out about this, felt an invasion of privacy and decided to end the therapeutic relationship.14 In this case the doctor may argue having acted under the concept of beneficence, but with consequences completely opposite than those expected. To access SNs with the patient's consent may offer the doctor important information and it may be productive for his/her treatment, but doing this without the patient's consent may lead to a loss of doctor–patient trust.11

The use of SNs has substantially impacted the work and private life of health professionals. A good example of this is the competence for admission to general medicine programs at a higher education system, as well as in the working environment, with interview processes, personal or standardized evaluations and panels of representatives that usually make a decision, at the end of the process choosing the candidate with a certain group of characteristics desirable for an institution. To make use of the information available on SNs constitutes another area of controversy in the selection processes mentioned above. Almost 70% of human resources professionals from different institutions admitted to having used SNs to obtain information about a candidate, significantly influencing their acceptance/rejection decision for a professional position.15 In a survey conducted among directors of programs of medical residencies, 17% had used a SN to assess a candidate, modifying the candidate's place in a priority list in 33% of these cases.16 In our study of candidates for an orthopedic surgery residency, it was found that near half of them (200 candidates) had a SN profile. Our of these, 85% did not have restricted access to them, and unprofessional content was found in 16%.17

Candidates should make sure their online profiles reflect standards of professionalism, as well as stress their academic strengths and personal accomplishments. This has certainly raised ethical and legal considerations, concepts like privacy, discrimination and professionalism.18

The use of portable smart devices like cellphones and tablets complicates the panorama regarding the preservation of privacy. In surveys, close to 20% of residents communicate with patients via email using their phones. Out of these, 73% did not have their device password-protected.19 This information, provided by the patient, would be at risk of being made public if the device were lost. The use of apps like Whatsapp, an extremely popular communication tool among medical colleagues, also leaves an electronic trace of information for an undetermined period of time: legal implications to making this information public have not yet been established. In a recent study, around 95% of medical students admitted to having used text messaging through their mobile phones to receive patients’ information, and out of these just 50% had security measures to access their device.20 While text messaging between the doctor and the patients or other colleagues can facilitate communication, most doctors fear these interactions may transgress privacy.1,21

- (c)

Maintaining limits in the doctor–patient relationship

It has been proven that patients are the ones who send “friend requests” via Facebook to their doctors, yet they respond to these requests on only a few occasions.22,23 In a recent study, around 35% of external doctors had received a friend request on Facebook, while the rate was closer to 8% for residents.23 In most cases, the doctors considered the requests to be unethical, either for medical or personal reasons. Indeed, all available guidelines suggest the rejection of these types of requests.

- (d)

Professionalism and e-professionalism

Health institutions have developed disciplinary guidelines with the purpose of ensuring an adequate public image. Some authors have even developed the concept of e-professionalism (e stands for electronic). Cain et al. define this concept as those attitudes and behaviors (some of which may occur in private) which reflect the paradigms of traditional professionalism, manifested through social media.24 This concept successfully translates the idea of professionalism, usually considered only in the “real world” and in specific contexts (work, academic), to the “online” world. It involves the way professionals present themselves in SNs and how it should be subjected to the same exigencies as the ones in their work environment.

Some factors which are believed to promote the lack of professionalism in SNs are the apparent state of anonymity and the perception of privacy by the user.25,26 Information which may question the prestige of the doctor or institution which he/she works for (for example, a video was uploaded to Youtube where a group of medical students were dancing mockingly with skeletons and drinking from skulls used as containers, making the logo of the implicated institution visible)27 or any content including explicit, sexual or offensive images involving alcohol or drug consumption can negatively affect the prestige of a doctor or student. A study of graduates of a medical school reports that 37% of the graduates who use any type of SN publish information like sexual orientation, marital status, religion and pictures of themselves intoxicated by different substances.28

Emphasis must be made on the fact that shared information through SNs is subject to the same standards of professionalism as any other interpersonal interaction.

Almost 60% of North American medical schools report incidents involving students and the publication of unprofessional content on their SNs.29

Surveys conducted show that most medical students agree with the idea of professionalism in the work environment (either clinic or hospital), while only 43% believed that this also applied to their “spare time”.30 This proves an important discrepancy between what the students understand of professionalism and what they believe is appropriate or inappropriate in their online behavior through SNs. At the same time, the defamatory or inappropriate content of this information can be utilized in a judiciary context as evidence for which the author is legally responsible.25,26 Nevertheless, the legal boundaries regarding the concept of privacy are not entirely clear.18

- (e)

Regarding colleagues

Considering that the main function of SNs is to promote communication and interconnectivity among users, not surprisingly many times the first to notice professional transgressions are colleagues. This brings a whole new set of ethical dilemmas into the medical practice. Should a doctor, resident or student report this activity to the authorities of the institution? Guidelines suggest in the first instance to approach the implicated colleague, and turn to the authorities only if, despite the intervention, there is no change in the content or conduct of the implicated person.1,25,26

Another important point regarding medical ethics is that, under certain circumstances within the professional medical environment, it is considered an obligation to report any medical disability or incompetence, when there is evidence. Disability refers to a process which impedes proper execution of the medical practice as a result of an illness (i.e. dementia) or substance abuse (i.e. alcoholism), while incompetence refers to a lack of knowledge or the necessary abilities. What would the implications be of obtaining information about a colleague's medical inability or incompetence from a SN? For example, a surgeon may reveal, only to a few people through their SN, that he has early Parkinson's disease. Based on the principle previously mentioned, one would be obliged to report this situation to the authorities of the institution, or in some cases the police. These circumstances represent ethical, professional and legal dilemmas, which are still in the process of being solved.

Social networks in psychiatryThe incursion of SNs in medical practice has presented particular challenges and benefits in psychiatry. 95% of psychiatry residents have SN pages, about 10% of them have received friendship requests from their patients, and 18% have entered some of their patients’ SN pages.23 We have commented specific cases where privacy and trust have been transgressed in the patient–therapist relationship.

Concepts like addiction to SNs, can become a new diagnosis and a great challenge in modern psychiatry.31 On the other hand, the use of social media has opened new lines of investigation and evaluation opportunities. For example, a recent study proved that SN activity (number of pictures, friendships, amount of information, usage hours, etc.) can predict the type of personality disorder (schizotipy) in a group of outpatient subjects.32

The impact of SNs on psychiatry is vast and will remain in constant change and evolution for years to come.

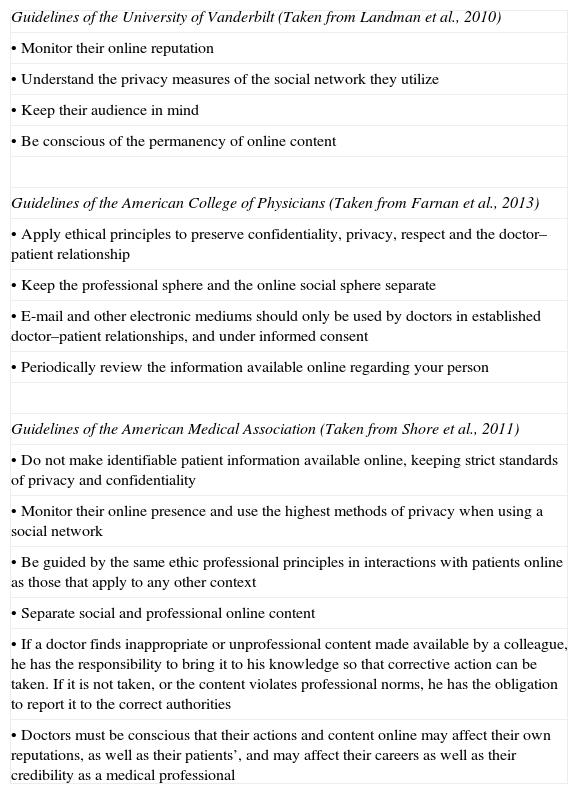

Guidelines and recommendationsDespite the uncertainty surrounding the use of SNs in a medical context, several professional associations have accomplished major advances in the regulation of these activities. Some have even published formal recommendations, as well as specific guidelines, like the American College of Physicians at the University of Vanderbilt and the American Medical Association, among others.1,2,33 However, the universalization of these guidelines has been slow and incomplete.

In a study where web pages from 132 accredited medical schools (in the USA) were being evaluated, only 10% had guidelines or policies which mentioned in a specific manner the proper way of utilizing SNs for their students.34 Summaries of some of these guidelines can be found in Table 3.

Guidelines to follow in the use of social networks.

| Guidelines of the University of Vanderbilt (Taken from Landman et al., 2010) |

| • Monitor their online reputation |

| • Understand the privacy measures of the social network they utilize |

| • Keep their audience in mind |

| • Be conscious of the permanency of online content |

| Guidelines of the American College of Physicians (Taken from Farnan et al., 2013) |

| • Apply ethical principles to preserve confidentiality, privacy, respect and the doctor–patient relationship |

| • Keep the professional sphere and the online social sphere separate |

| • E-mail and other electronic mediums should only be used by doctors in established doctor–patient relationships, and under informed consent |

| • Periodically review the information available online regarding your person |

| Guidelines of the American Medical Association (Taken from Shore et al., 2011) |

| • Do not make identifiable patient information available online, keeping strict standards of privacy and confidentiality |

| • Monitor their online presence and use the highest methods of privacy when using a social network |

| • Be guided by the same ethic professional principles in interactions with patients online as those that apply to any other context |

| • Separate social and professional online content |

| • If a doctor finds inappropriate or unprofessional content made available by a colleague, he has the responsibility to bring it to his knowledge so that corrective action can be taken. If it is not taken, or the content violates professional norms, he has the obligation to report it to the correct authorities |

| • Doctors must be conscious that their actions and content online may affect their own reputations, as well as their patients’, and may affect their careers as well as their credibility as a medical professional |

These guidelines may be very effective, and some positive tendencies can be discerned from a review of medical literature. Even when the amount of doctors who have admitted having a SN page is on the rise, from numbers under 15%,29 up to studies where between 73 and 85% have them,22,23 the proportion that have public profiles has decreased, from 50–67%29,33 to 12%.23 This indicates the increasing popularity of SNs as well as a possible rise in consciousness on behalf of healthcare professionals regarding the use of the highest and most strict privacy measures.

How can “e-professionalism” be taught?All of the above recommendations make clear the need to include this topic in medical education programs. There have been studies conducted which have made useful recommendations for the teaching of electronic professionalism to doctors and medical students. A simple spreading of the guidelines may be insufficient. The use of scenario simulation where professionalism is violated on SNs, as well as suggestions of use, can be valuable interventions.35 Mentor observation and the presentation of examples of the proper use of SNs are an important part of the education of students of the medical field.26 In a study, it was demonstrated that after going to a class where they presented specific cases of violation of online professionalism, explaining the consequences and the steps to follow in detail, a group of radiology residents had acquired a better understanding of the professionalism and importance of preserving the confidentiality and privacy of their patients and colleagues.36 These simple interventions seem to be effective, even after a single academic session.

ConclusionsIt is clear that the popularity of SNs does not seem to be slowing down. It is more and more common for doctors, residents, students and healthcare professionals to interact, one way or another, through electronic media and SNs, whether among themselves or with their patients. This fact has been associated with different ethical, legal and professional difficulties, some of which we have reviewed. However, there are specific guidelines formulated to face these challenges. Moreover, these mediums have opened new ways to improve medical learning and healthcare management. Institutions should adopt or create guidelines which ensure a professional and proper use of SNs, and its training should be a regular part of the curriculum in faculties of medicine. This way, healthcare professionals will be better prepared to face the challenge which we are facing in modern technology era.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.