Psychosomatic disorders are among the most common psychiatric disorders in general practice, with a prevalence of 16%. These patients often turn to different general practitioners and/or non-psychiatric specialists for long periods of time and represent a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge, as the possible organic component makes it complex and difficult to manage.

The reported case is a 24-year-old male patient with a diagnosis of Somatic Symptoms Disorder and multiple psychiatric comorbidities. The purpose of this study is to review the reconceptualization of Somatoform Disorders’ DSM-5 diagnosis, which can be useful for psychiatrists and non-psychiatric physicians for the approach and management of these patients.

Psychosomatic disorders are among the most common psychiatric disorders in general practice, with a prevalence of 16%.1–3,5 Before going to a psychiatrist, these patients usually see general physicians and/or non-psychiatric specialists for long periods of time2,4,6 which is enabled by these patients’ resistance to acknowledging that their physical problem can be linked to or exacerbated by an emotional and not only an organic origin, resulting in multiple therapeutic managements and chronic use of health services.2,4,5,8

Moreover, the important association of psychiatric comorbidity (depression, anxiety and psychopathology of character), as well as medical illnesses,1,2,4,6,7 makes them a diagnostic and treatment challenge not only for the psychiatrist, but also for general practitioners and other specialties, since the possible organic component makes them complex and difficult to manage.4,7

Regarding its evolution, chronicity, social and interpersonal dysfunction, difficulties at work and the frequent use of medical services are the common characteristics of these disorders, which lead to an elevated level of dissatisfaction in both the doctor and the patient.5,7,8 The present article presents the case of a patient who exemplifies this pathology.

Case presentation and discussionThe patient is a 24-year-old male, from Monterrey, Mexico. He is single, works at a flea market, with an upper secondary level of completed education and a low socioeconomic status. He had a background of excellent school performance with academic scholarship through secondary school and high school. Prior to the onset of the psychopathology, there was adequate and constant work activity, as well as more social, recreational and interpersonal involvement. During his childhood, he refers to being sexually abused (improper touching) on two occasions and describes a stressing family environment with constant verbal and psychological abuse toward him and other family members. This prolongs until adolescence. Subsequent to his parents’ separation, he maintains a scarce, almost null, relationship with his father, which stands as an event which impacts his childhood and personal development in a negative way.

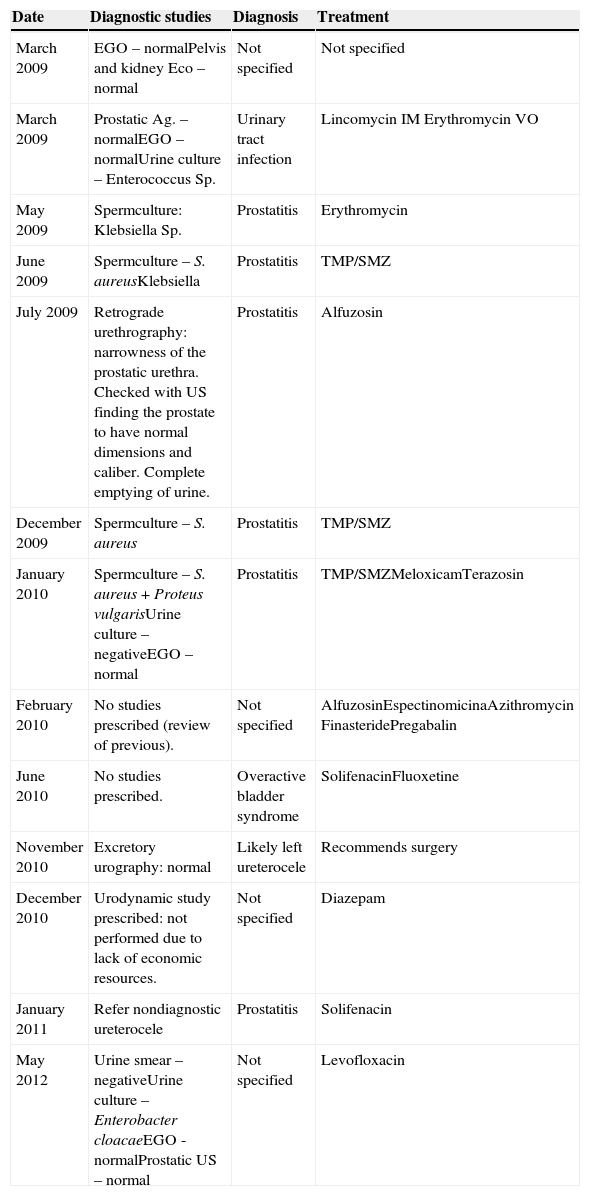

He has attended the Psychiatric Outpatient Clinic voluntarily on July 2012 after presenting depressive symptoms for more than 6 months, secondary to pollakiuria with an evolution of 4 years, which began after his father's death, presenting 20–25 urinations a day, with intervals of 10–20min in-between and without disrupting sleeping hours. He denies pain while urinating, pushing, tenesmus, fever or any other added symptoms. Over 4 years the patient saw multiple doctors and different urologists, who requested para-clinical studies, with different non-certain diagnoses and diverse pharmacological treatments without improvements in the urinary symptom. (Table 1)

Medical history in relation to the urinary symptom.

| Date | Diagnostic studies | Diagnosis | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| March 2009 | EGO – normalPelvis and kidney Eco – normal | Not specified | Not specified |

| March 2009 | Prostatic Ag. – normalEGO – normalUrine culture – Enterococcus Sp. | Urinary tract infection | Lincomycin IM Erythromycin VO |

| May 2009 | Spermculture: Klebsiella Sp. | Prostatitis | Erythromycin |

| June 2009 | Spermculture – S. aureusKlebsiella | Prostatitis | TMP/SMZ |

| July 2009 | Retrograde urethrography: narrowness of the prostatic urethra. Checked with US finding the prostate to have normal dimensions and caliber. Complete emptying of urine. | Prostatitis | Alfuzosin |

| December 2009 | Spermculture – S. aureus | Prostatitis | TMP/SMZ |

| January 2010 | Spermculture – S. aureus + Proteus vulgarisUrine culture – negativeEGO – normal | Prostatitis | TMP/SMZMeloxicamTerazosin |

| February 2010 | No studies prescribed (review of previous). | Not specified | AlfuzosinEspectinomicinaAzithromycin FinasteridePregabalin |

| June 2010 | No studies prescribed. | Overactive bladder syndrome | SolifenacinFluoxetine |

| November 2010 | Excretory urography: normal | Likely left ureterocele | Recommends surgery |

| December 2010 | Urodynamic study prescribed: not performed due to lack of economic resources. | Not specified | Diazepam |

| January 2011 | Refer nondiagnostic ureterocele | Prostatitis | Solifenacin |

| May 2012 | Urine smear – negativeUrine culture – Enterobacter cloacaeEGO - normalProstatic US – normal | Not specified | Levofloxacin |

At first, in view of the diagnostic doubt and lack of response to treatments, the patient thought that the origin of the symptom was caused by a physical illness; then, he associated it with the unresolved mourning of his father's death which concurs with the onset of the symptoms.

Secondary to the onset of the urinary symptom, the patient interrupts his personal and professional growth: quits his job, stops frequenting his friends and remains isolated at home for over 2 years, focusing his life on attending specialists and trying to solve his symptoms. Two years later, the patient reduces the frequency of urination, accomplishing a urination rate of once every 2h, and begins working part-time. However, the sense of urgency to urinate as well as the constant preoccupation of not being able to reach a place to urinate, lead to a poor working growth and avoidance of interpersonal relationships with limited social and recreational activities.

Six months prior to attending psychiatric consultation he begins to feel sadness every day for almost the entire day; this sadness is linked to his urinary problem and his difficulties in accomplishing things in his personal life and at work. He refers to feeling “handicapped”, saying he felt “like trash”, occasional crying, anhedonia and melancholy. A month ago he began to present terminal insomnia, reduction of appetite, weakness and occasional feelings of hopelessness, causing significant discomfort which interferes with his performance in his everyday activities. He denies having thoughts of death, or suicidal thinking and/or planning.

Previous to the pollakiuria, a pattern of preoccupation about trivial situations with a tendency for the catastrophic is noticed, which causes a persistent and general anxiety not limited to a specific situation and is manifested by constant hand sweating, palpitations, mild tremors, occasional irritability, fatigue and difficulty focusing. The anxiety symptoms fluctuate, but have a long evolution, which has been exacerbated over the last 6 months.

Structural examThe patient manifests evasive and dependent behavior, which has had him working for the last 2 years at a place which does not represent a significant challenge nor does it demand formal obligations, hiding behind his urinary problem to avoid looking for a stable job, with a dependent and victimized line. The evasive behavior is also manifested by his disproportional fear when facing everyday situations, generating anguish and resulting in deterioration of work and interpersonal relations.

He presents a predominately devaluated self-concept, describing himself as scared, insecure and feeling that he has little value; this interferes with his interpersonal relationships with others. He displayed defense mechanisms, mainly repressive, like rationalization, constantly using his urinary symptom as an excuse to justify his evasive and dependent traits; affective isolation when describing his father's death as an event that caused little pain and displacing, redirecting that pain toward his urinary symptom.

Despite his difficulty to relate to others, he manifests an ability to empathize with others and an ability to be grateful, expressing gratitude for the time dedicated to his evaluation. Regarding his aggressive impulses’ control, he does not present frequent situations which put him in conflict, thus making his ability to contain and repress emotions evident. However, on a few occasions we were able to see the infiltration of primary process thinking, causing him to make impulsive decisions, later realizing this through his ability for self-reflexive thinking.

In respect to the quality of his interpersonal relationships, he is unable to establish long lasting friendships or romantic relationships and maintains a superficial and not very affective relationship with his family members. Regarding his tolerance of anxiety, we can observe a perennially apprehensive tendency and a tendency to exaggerate catastrophes, which is expressed through his urinary frequency and in everyday situations, like sweaty palms when interacting with people, and in his sex life, presenting anticipatory anxiety of not reaching a full erection.

Despite observing in the patient the cognitive ability and desire to develop the personal and professional aspects of his life, he does not perform any type of activities where he experiences pleasure and satisfaction.

The patient has self-reflexive ability to suggest that pollakiuria is the superficial symptom covering deeper problems related to self-esteem and his character.

DSM-V diagnosis300.82. Somatic Symptom Disorder.

300.02. Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

296.21 Major Depressive Disorder.

3001.9 Unspecified Personality Disorder.

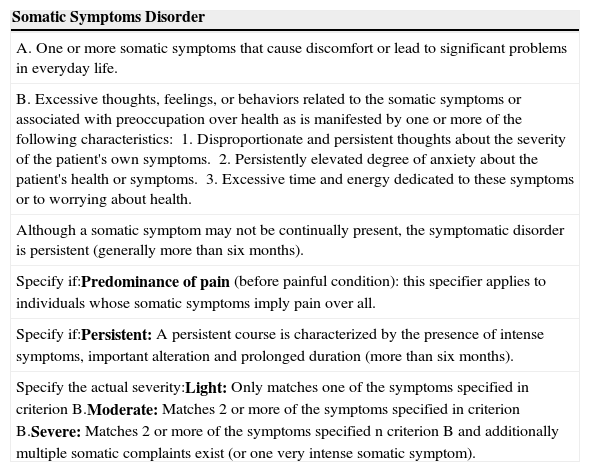

Diagnostic analysisThe DSM-V modifies the Somatomorphic Disorders and creates a new diagnostic entity in its place; Somatic Symptoms Disorder (SSD) and related disorders. Evidence of multiple lab and imaging studies without significant pathological findings, which explain the severity of the symptoms, along with the lack of response to several medical treatments given by different urologists, ruled out the presence of a known medical condition that could explain the patient's urinary symptom, thus concluding, according to the DSM-V, the presence of a SDD (Table 2).8

Diagnostic criteria for Somatic Symptoms Disorder DSM-V.

| Somatic Symptoms Disorder |

|---|

| A. One or more somatic symptoms that cause discomfort or lead to significant problems in everyday life. |

| B. Excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviors related to the somatic symptoms or associated with preoccupation over health as is manifested by one or more of the following characteristics:1. Disproportionate and persistent thoughts about the severity of the patient's own symptoms.2. Persistently elevated degree of anxiety about the patient's health or symptoms.3. Excessive time and energy dedicated to these symptoms or to worrying about health. |

| Although a somatic symptom may not be continually present, the symptomatic disorder is persistent (generally more than six months). |

| Specify if:Predominance of pain (before painful condition): this specifier applies to individuals whose somatic symptoms imply pain over all. |

| Specify if:Persistent: A persistent course is characterized by the presence of intense symptoms, important alteration and prolonged duration (more than six months). |

| Specify the actual severity:Light: Only matches one of the symptoms specified in criterion B.Moderate: Matches 2 or more of the symptoms specified in criterion B.Severe: Matches 2 or more of the symptoms specified n criterion B and additionally multiple somatic complaints exist (or one very intense somatic symptom). |

The urinary symptom generated discomfort and major anxiety which impacted the different areas of the patient's life in a negative way, since the constant feeling of inability hindered his development in his work, social and personal life (Criterion A). The symptom became the center of his life, and he devoted excessive time and energy worrying about his health and searching for an effective treatment for over 4 years (Criteria B and C). The sudden onset, with a persistent course and long evolution of a single very severe somatic symptom, producing marked anxiety and disability in his everyday life, specifies the diagnosis as Severe Persistent Somatic Symptoms Disorder.

The new components of somatic symptoms disorders are incorporated in this new edition of the DSM-V: affection, cognition and behavior within SSD criteria, providing a more accurate and more comprehensive vision of the patients’ real signs and symptoms, in comparison to the DSM-IV, which evaluates only somatic symptoms (1 or more). This diagnostic reconceptualization provides a useful tool for primary care doctors or any other non-psychiatrist specialist. This could be very beneficial in order to reach a proper diagnosis and treatment in an earlier manner, improving the prognosis and avoiding economic expenses in healthcare.6,7,9,10

Additionally, the criteria for a major depressive disorder, with a moderate single episode, are met, clinically evident and verbally expressed by the patient.

Regarding anxiety symptoms, these were reported before the onset of the urinary symptom, with exacerbation in the last 6 months, causing significant discomfort. The non-specified personality disorder is justified by presenting evasive traits manifested in social inhibition, feelings of inability, hypersensitivity to negative evaluation and avoidance of activities which require significant interpersonal contact, causing clinically significant dysfunction and discomfort in social, work and interpersonal areas. We can also observe dependent personality traits with the patient's difficulty to make decisions and not assuming responsibility according to his age and stage in life.

Therapeutic planWhen SSDs coexist with a mood or anxiety disorder, the administration of psychiatric medications is indicated, along with a psychotherapeutic treatment. Therefore, we decided to follow a combined treatment.2,5,12–14

Pharmacological treatmentThe pharmacological treatment approach to SSDs has been complicated due to the lack of conceptual clarity and excessive emphasis on the psychosocial causation and efficacy of psychological treatments.15 Every type of psychiatric medication is used in clinical practice to treat SSDs, and there are systemic studies focused on five main medication groups: tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), inhibitors of serotonin reuptake (SRI), serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), atypical antipsychotics, and herbal-based medications.12,15 Evidence shows that these five groups are effective for a wide variety of disorders and that all types of antidepressants seem to have certain degree of effectiveness on SDDs and related disorders.12,13,15 TCAs and SRIs are the most utilized pharmacological agents in SSDs. Nevertheless, there are little data supporting its effectiveness as a stand-alone treatment.2,5,12,13

The research leaves many unanswered questions about dosage, treatment duration, improvement sustainability in the long run and variability in responses to different types of medications.15 According to Carlat (2012) the evidence of somatic treatment of depression in adults reports sertraline to be a first-choice antidepressant that is hard to top, given its combination of efficacy, tolerability and low cost.16

In the reported case, 50mg of sertraline/day is prescribed, along with long-acting benzodiazepine (clonazepam 0.5mg) at night due to the presence of comorbidity with depression and anxiety. The depression symptoms are resolved within 2 months; however, doctors decided to double the sertraline dosage (100mg) at 6 weeks and triple it (150mg) at 3 months due to the persistence of the anxiety symptom. The urinary symptom occurs with less frequency until it is fully resolved after 6 months of combined treatment. Clonazepam is suspended after 4 months due to a good response to the antidepressant and to avoid dependence on the medication. Because of the significant improvement in the urinary symptom as well as the depressive and anxiety symptoms, SRI is gradually reduced to 50mg/day until its full suspension 2 years later. The patient tolerates the medication adequately without any report of significant adverse side effects.

Psychotherapeutic treatmentFrom the non-pharmacologic treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) proved to be the most effective; however, these interventions have not been proven efficient in the long run.5,12,13 According to Kaplan and Sadock, in both the individual and group psychotherapy fields, the idea is to help patients face their somatic symptoms, express subjacent emotions and develop alternative strategies to express their feelings. Additionally, some results indicate that psychodynamic psychotherapy is beneficial to psychosomatic patients, where the therapeutic alliance plays an important role and is solidified through empathy with the patient's suffering.17

Doctors are not recommended to face patients who somatize with comments like “It's all in your head”. Instead, they must recognize the reality of the physical ailments, even if they understand that their origin is basically intrapsychic.2,4,5 An easy route of entry into the emotional aspects of physical suffering is the examination of its interpersonal ramifications in the patient's life.7,17

We decided to begin with individual, expressive psychodynamic psychotherapy, with a focus on object relations, twice a week, in 45–50-min sessions. During the first 6 months they included behavioral techniques focused on the urinary symptom. These techniques consisted of: emptying the bladder every 2h, going to the bathroom only to wash his hands and/or face and performing jaw exercises.

In parallel to the pharmacological treatment, the patient commits to psychotherapeutic treatment, with results which impacted his life in a positive way; he enrolls in university, takes responsibility for his school expenses and his treatment and gradually becomes involved in social and recreational activities. The patient continues with psychodynamic psychotherapy to keep working on his evasive and dependent personality traits, which contributed to the onset of the physical symptom and the subsequent personal and professional deterioration.

Therapeutic plan analysisThe combination of treatments (pharmacological/psychotherapeutic) can be necessary in patients with severe SSD of a long evolution as in the case presented, even more when there is a comorbidity with depression and/or anxiety. Consequently, despite the fact that there is no compelling evidence for the effectiveness of antidepressants in SSDs, the choice was based on tolerability, therapeutic efficiency in depression and anxiety and low cost, given the patient's economic problems.

Despite the psychotherapeutic treatment of choice of SSDs being CBT, above the pharmacological treatment by itself or any other type of psychotherapy, these types of interventions have not been proven to be effective in the long run, since most clinical trials only evaluate results in the short-term. In this case, the patient attends the psychiatric outpatient clinic with the idea and hope that his physical symptom may have a psychological cause; as well as a great motivation to improve his personality aspects which prevented him from relating to others. Therefore, it is decided in conjunction with the patient to begin a long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy process complemented with behavioral techniques. The success of the treatment obtained thus far seems favored by a good therapeutic alliance, self-reflective ability and commitment to the treatment.

ConclusionsThe common characteristic evolution of chronicity, social dysfunction, work difficulties and frequent use of medical services lead to a level of dissatisfaction and frustration on the patient as well as the doctor, as well as a high economic cost in healthcare services.2,4,5,18

One of the most valuable contributions in the re-conceptualization of the DSM-V for somatic disorders is that it obliges all non-psychiatric colleagues in the mental health area to place stress, not on the description of the symptom per se, but in exploring how the symptom affects the patient: (a) emotionally (i.e. makes him depressed, anguished, irritated, etc.); (b) cognitively (i.e. rumination on the symptom, catastrophic ideas, etc.); and (c) behaviorally (i.e. constant medical consultations, stop working, etc.).8

Even though the chief complaint was pollakiuria, by understanding how it affected the patient, not only physically, but also in other aspects of his life and his surroundings, it helped us situate the functioning of the symptom in his life, to have a more realistic idea of the patient's ailment and to have a more empathic treatment toward him. This more integral approach allowed the creation of a treatment plan which included not only the symptom, but other aspects of the patient's life which were subjacent to the physical symptom.

The DSM-V modifications in SSD diagnostic criteria lead all healthcare professionals toward a more integral evaluation and approach, which may help doctors to have a more realistic comprehension of the patient, thus avoiding improper or incomplete diagnosis and/or management, which only favors chronicity and worsens prognosis.6,7,9–11,18

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

FundingNo financial support was provided.