To identify the causes due to which potential blood donors do not make voluntary donations: lack of knowledge, attitude, and the perception of blood donations as unwholesome.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a transversal, observational, descriptive, prospective, and a survey-based study of 435 subjects in Monterrey, Mexico in November of 2011.

Results135 (31%) subjects were already donors, of which only 16 (3.6%) did it altruistically. Of the total amount of subjects, 161 (37%) were associated with some benefits from donating blood, 154 (35%) identified some kind of damage, the most mentioned was transmission of diseases with 77 (50%) mentions. The most common cause of refusal toward donation was “saving blood for a relative in need” with 137 (33%) mentions. Of the subjects surveyed, 55% (n=240) refer having very few thoughts for donating blood voluntarily. Also, 360 (86%) subjects will donate without expecting something in return. Finally, 348 (80%) subjects do not remember seeing or hearing any kind of promotional information about altruistic blood donation.

ConclusionsA great deal of people will donate blood altruistically without receiving any reward for doing so. 80% of the subjects do not remember seeing or hearing any kind of advertisement for blood donation which is proof of lack of adequate publicity. The analysis of perception of damages or benefits from blood donation will help in the development of more focused blood donation campaigns.

There are three blood donation modalities: altruistic volunteers, family reposition and paid donors. In Mexico, paid donation is illegal as cited in article 462 of the Health Law.1 Volunteer non-paid blood donors are vital to ensure safe blood supply and guarantee blood reserves. A well-established non-paid volunteer donation program significantly contributes in reducing the risk of transmission of infections like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B, hepatitis C and syphilis, which are all attributable to transfusion.2 In our country these aspects are regulated by the Official Mexican Standard (NOM by its Spanish acronym) NOM-253-SSA1-2012.3

In 1999 there were only 26 countries which obtained the totality of donated blood from non-paid volunteer donors, by 2002 this number increased to 39 and by 2005 the number had gone to 50, the following year, 4 more countries joined and the number keeps growing. There are currently 62 countries in the world where the blood supply is 100% or almost 100% (99.9%) by non-paid volunteer donors.4–6

This research paper is based on international strategies from the World Health Organization, which recommends the undertaking of the Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice studies (KAP) related to blood donation at a local level. With these studies, one can better know the sector of the population, know the donor, and the potential donor. They provide a solid base to the donation services approach, and are helpful in identifying similarities, finding adequate messages and selecting the most effective channels to reach said audiences.7

The World Health Organization's goal is to have the totality of their member countries that obtain the full 100% of their blood supply from altruistic donors by the year 2020. Under this premise, international collaboration groups have been created, as well as a series of strategies and guidelines for its implementation. At the same time, we have identified within our local environment the need to increase the number of altruistic or volunteer non-paid donations, thus it is necessary to identify the causes of why potential donors do not go through with their donations.8 Once the causes and the potential donors’ perception toward volunteer donations have been identified we will be able to create better strategies to reach the goal of 100% of volunteer, non-paid donations by the year 2020.

Materials and methodsA transversal, observational, descriptive, prospective study was conducted. A survey was administered to 435 subjects in a single period in Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico during the month of November 2011.

Subjects between the ages of 18 and 65 years were interviewed. Those under 18 years and older than 65 were excluded, as well as subjects who were linked to the health area, because they might be sensitized about blood donation and would probably have technical knowledge on the subject outside the usual among the general population. Other people excluded were those related to people currently admitted in a hospital. Incomplete questionnaires were eliminated.

A preliminary survey consisting of 12 questions was designed and evaluated by an expert panel based on their experience in the field of blood donation.

The instrument was redesigned according to the recommendations of the expert panel, increasing the survey to 14 questions. We trained a group of volunteer non-professional pollsters on the basic requirements of the survey and a preliminary sample of 120 surveys was performed in order to evaluate the instrument and the pollsters’ ability to apply it.

Once the preliminary data was collected and analyzed, as well as the people's response to the instrument, feedback, and the pollsters’ skill for its application, some questions were redesigned until reaching an instrument which was comprehensible to most people, easy to answer and apply, and flexible.

Having done this, and with the final draft, 600 surveys were conducted, divided into blocks of 50 units by pollster. 133 surveys were not conducted or were conducted improperly. Finally, 467 surveys were collected, of which 32 had incomplete data. The final sample consisted of 435 properly completed surveys.

Population characteristics were described using socioeconomic status based on percentages. Association measures were performed in order to establish causal inference with calculation of relative risk and impact measures with the calculation of attributable risk between the variables of refusal of donation and damages caused by donation. The statistical software SPSS V20 was used.

The anonymity of the respondents was maintained under the confidentiality principle: all obtained information on the present project was considered confidential. The Ethics Committee of the medical area of the Autonomous University of Nuevo León authorized the study to take place in the form of a survey.

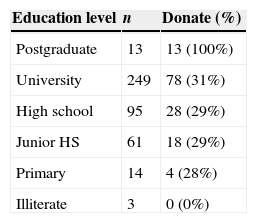

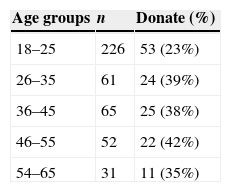

ResultsOut of the total of the respondents (n=435), 224 (51%) were female and 211 (49%) were male. The relation between the highest level of education and the percentage of blood donation for each studied group was evaluated (Table 1). They were divided into age groups, the group of 18–25 years was the group with the most respondents with 226 (52%) subjects. The percentage of donors for each age group was calculated (Table 2).

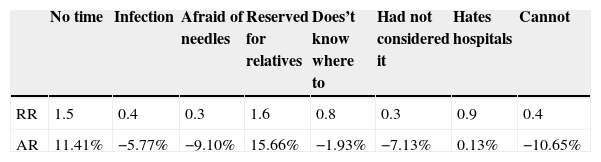

Out of the 435 completed surveys, 135 subjects had previously donated, but only 16 (3.6%) had done it altruistically. Out of all surveyed subjects, 161 (37%) linked benefits to donation, 154 (35%) identified some damage associated with the donation, the transmission of infections being the most frequent with 77 (50%) mentions. Relative risk (RR) calculated for not donating because of the fear of infection transmission was 1.11 (a positive association to not donating), with an attributable risk (AR) of 1.4%. RR and RA were calculated for every negative of donation mentioned by the respondents (Table 3)

Relative risk and attributable risk for refusal to donation.

| No time | Infection | Afraid of needles | Reserved for relatives | Does’t know where to | Had not considered it | Hates hospitals | Cannot | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| AR | 11.41% | −5.77% | −9.10% | 15.66% | −1.93% | −7.13% | 0.13% | −10.65% |

RR: relative risk; AR: attributable risk.

The number of people belonging to some civil charity or similar altruistic association was 45 (10%) respondents, from which 17 had already donated blood before and 4 (10%) did it altruistically. The percentage of people who did not belong to civil associations and donated blood voluntarily or altruistically were 2.7% (n=12).

The knowledge of the donation process showed that 227 (52%) respondents knew the process versus 208 (47%) who did not. Moreover, 55% (n=240) of respondents mentioned having considered donating blood a few times or not at all. Also, 360 (86%) subjects did not expect to receive anything in return for their donation; once that had been established, subjects were asked that in the case of receiving some compensation for their blood, what would urge them to donate voluntarily, 234 (53%) responded that they would do it out of personal satisfaction. Lastly, 348 (80%) of the subjects do not remember having received any type of promotional information to donate blood.

DiscussionSocio-demographic distribution of the respondents could not be demonstrated due to the fact that a third of the surveyed subjects did not know or refused to provide information about their estimated monthly family income. No important variables were found in donation habits among the educational level groups analyzed. Surveyed subjects who had donated voluntarily in the past show what the current state of the country is, with low rates of altruistic donations in every sector.

The damage associated with blood donation most frequently mentioned in the surveys has been the transmission of infections; it was evaluated as a negative factor for donating, thus placing it as a priority to eliminate; even though the attributable risk was low (1.11%) in the no-donor group, it also has an impact in the donor group which would place it as a member-losing factor within the group.

The analysis of refusal of donation through risk assessment determined that if we were to eliminate the two main causes (reserved for a family member and not having time to donate) blood donation would increase by up to 26%. Given the difficulty of modifying potential donors’ time frames, we must focus on reducing the perception of having to “reserve” oneself from donating only when a family member requires it. This could increase blood donation by up to 15.66%

Being a member of a voluntary group increases altruistic donation fourfold, even if the group is reduced to evaluate statistical significance; references on this matter in other studies suggest this as feasible.9

Approximately half the respondents ignored the process to donate blood, also about half of them mentioned having thought about voluntarily donating a few times or not at all, which shows that one cannot think about what one does not know.

Contrary to what could be suggested to attract a larger number of possible donors, the offer of prizes or handouts, including cash in exchange of the donation was not well-received, because 86% of the subjects mentioned not expecting anything in return for their contribution, out of these about half mentioned that they would donate just for the satisfaction itself. However, we must point out that 55 (13%) people said that there was nothing in the world that would make them feel drawn toward donating blood, which proves that there is always a percentage of the population which will remain reluctant to any scouting strategy.

About 80% of the surveyed people did not recall any type of promotional information that invited them to donate blood voluntarily; this shows the lack of diffusion of the programs and the need to increase the frequency, duration and penetration of said programs.

The idea of associated damages linked to donation, like transmission of infections, the lack of knowledge of the donating process, the low percentage of people who think about donating, and above all, the overwhelming amount of respondents that do not recall hearing or reading promotional information inviting them to donate blood voluntarily are unequivocal signs of the lack of promotion of altruistic (non-paid) donation. The perception of associated risks and the reasons for refusal are factors which can be improved; the subject's lack of time can be compensated by a preferential treatment of the altruistic donor in blood banks, making him wait as little as possible, thus reinforcing the idea of donating regularly; the fear of the damages associated with donation can be overcome with the diffusion of scientific knowledge on the matter and by increasing the will to help; a high percentage of subjects were willing to donate without receiving anything in return, which represents an important area of opportunity, since it indicates that the spirit of solidarity is present, it just need to be promoted and directed with proper planning and adequate strategies specific to our population.

Other proven strategies in different parts of the world are the formation of donor groups like the model “club 25” which consists of inviting students between 18 and 25 years of age to donate voluntarily 25 times before turning 26. These groups can be created within universities with the help of volunteers, inviting other students to donate blood just for the pleasure of helping others. These clubs maintain communication with local blood banks to be informed of blood needs and to continuously receive specialized information and counseling which allows them to donate blood in a safe manner.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

FundingNo financial support was provided.

- 1.

Write down the gender of the respondent

- 2.

How old is the respondent?

- 3.

What is your highest level of education?

- 4.

How much is your monthly income (estimate)?

- 5.

Do you belong to a civil association, Rotary, National System for Integral Family Development (DIF), Volunteer ladies, etc.?

- 6.

Have you ever donated blood?

- 7.

Do you know the steps involved in blood donation?

- 8.

Do you know the benefits obtained when donating blood?

- 9.

Do you know any damages which you may suffer when donating blood?

- 10.

Have you ever considered going to donate blood?

- 11.

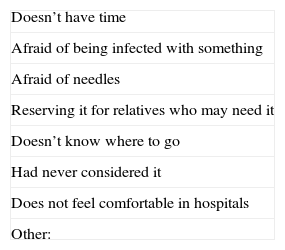

Refusal of donation. Why not to donate?

- 12.

Do you consider it necessary to receive something in return of donating blood?

- 13.

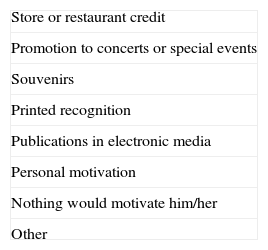

What would motivate you to donate blood?

- 14.

Do you recall ever seeing any type of information or ad to prompt you to voluntarily donate blood here in Nuevo Leon (excluding “blood needed for…” ads?