Co-infection by two or more pathogens is a common finding in infectology. However, the simultaneous infection by two viruses such as the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS CoV-2) has not been reported to date. In the context of a coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), any infectious clinical condition is suspected of COVID-19. The lockdown of the population sometimes makes us forget that other pathogens can also be transmitted and manifest themselves.

A 19-year-old French woman, with no relevant history, came to the emergency department with a two-day history of fever, bilateral eyelid oedema, and right hemifacial swelling. In addition to the skin manifestations, the physical examination showed bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy, non-suppurative pharyngotonsillitis, and splenomegaly.

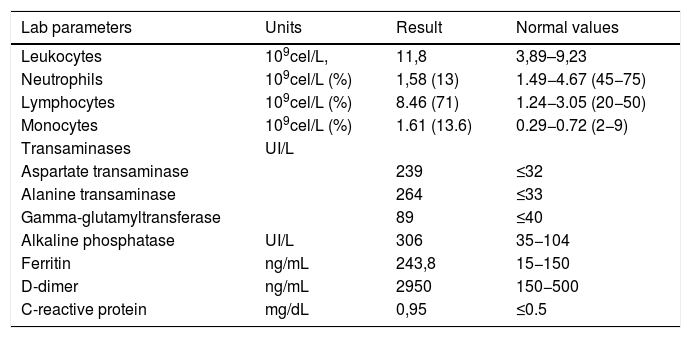

The results of the lab tests and the serological study are summarized in Table 1. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in the reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of the sample obtained by oronasopharyngeal swab. The presence of EBV was also detected by PCR in blood (4700 copies/mL) and plasma (9600 copies/mL). The mumps virus could not be detected in the saliva cell culture. An anteroposterior chest radiograph and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen showed splenomegaly (diameter greater than 16 cm) in the absence of pulmonary pathological findings. With a diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis (IM) mimicking mumps and asymptomatic Covid-19, in the absence of other complications, exclusively symptomatic and supportive treatment was recommended. The patient experienced a significant clinical improvement after two weeks of follow-up.

Lab and serological results.

| Lab parameters | Units | Result | Normal values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes | 109cel/L, | 11,8 | 3,89–9,23 |

| Neutrophils | 109cel/L (%) | 1,58 (13) | 1.49−4.67 (45−75) |

| Lymphocytes | 109cel/L (%) | 8.46 (71) | 1.24−3.05 (20−50) |

| Monocytes | 109cel/L (%) | 1.61 (13.6) | 0.29−0.72 (2−9) |

| Transaminases | UI/L | ||

| Aspartate transaminase | 239 | ≤32 | |

| Alanine transaminase | 264 | ≤33 | |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase | 89 | ≤40 | |

| Alkaline phosphatase | UI/L | 306 | 35−104 |

| Ferritin | ng/mL | 243,8 | 15−150 |

| D-dimer | ng/mL | 2950 | 150−500 |

| C-reactive protein | mg/dL | 0,95 | ≤0.5 |

| Serology | IgM (Index) | IgG (Index) |

|---|---|---|

| EBV (CLIA) | +, (6.1) | +, (1.6) |

| Mumps (CLIA) | +, (5,6) | +, (3.9) |

| Rubella (Elecsys Rube test) | – | +, 159 IU/mL |

| Measles (CLIA) | +, (1,2) | +, (2.9) |

| CMV (Enzyme Immunoassay) | – | – |

| Parvovirus B19 (CLIA) | – | +, (7.5) |

| HIV (ELISA) | – | – |

IM is a clinical syndrome characterized by fever, weakness, bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy, pharyngotonsillitis, and splenomegaly. The pathogen responsible for most cases is herpesvirus 4 or EBV and to a lesser extent, cytomegalovirus (CMV). Other pathogens that cause mononucleosis syndromes are hepatitis viruses, coxsackie A, parvovirus B-19, and HIV, but not coronaviruses. The patient had common laboratory abnormalities in IM, such as lymphocytosis or hypertransaminasemia, although abnormally high ferritin or D-dimer lab values were simultaneously observed, typical of COVID-19. Although fever is common in both COVID-19 and IM, splenomegaly and cervical lymphadenopathy are not common symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection.1

Mumps or parotitis is not common in Spain since the introduction of the MMR vaccine (measles, mumps and rubella) in the vaccination schedule in 1981, although outbreaks have been reported in recent years in universities and student residences in young people born between the years 1990 and 2000.2 We were able to verify that the patient was immunized in France with the MMR vaccine at 12 and 16 months in 2002. The different clinical manifestations of IM include bilateral eyelid oedema and facial swelling mimicking mumps. In this case, and in the absence of the virus in the saliva sample, we interpret the elevation of the anti-mumps IgM antibody titre as a false positive. This serological cross reaction has been previously reported and attributed to EBV.3 On the contrary, serological cross-reaction with measles is not so common in EBV, so we cannot rule out that SARS-CoV-2 was also involved in this case. SARS-CoV-2 shares morphostructural similarities with paramyxoviruses and they all express class I membrane fusion proteins.4 Our patient did not present pulmonary abnormalities in the CT scan performed, showing exclusively laboratory abnormalities attributable to COVID-19, despite the immunosuppression that IM can induce. Some authors suggest that the stimulation or training of the innate immune response induced by other infections and vaccines would favour the early synthesis of interferon and Toll-like receptors, which could explain the benign course of COVID-19 infection in children and young adults.5

In conclusion, we consider it important not to ignore other pathogens in febrile syndromes during this pandemic, not being tempted to attribute new, previously unreported clinical manifestations, to SARS-CoV-2.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We wish to thank Dr. Melania Iñigo from the Department of Microbiology of the Clínica Universidad de Navarra in Madrid, for her essential collaboration in the diagnosis of this patient.

Please cite this article as: García-Martínez FJ, Moreno-Artero E, Jahnke S. Coinfección por SARS-CoV-2 y virus Epstein-Barr. Med Clin (Barc). 2020;155:319–320.