Following the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection in December 2019, in Wuhan, China, the large amount of information generated, especially by the media, is having a great emotional impact around the world1.

In spite of this, mental health has become a secondary concern and is even underestimated. Some recent studies have found a higher prevalence of depressive2, post-traumatic and anxiety3 symptoms in patients with or suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Regarding the material and methods of the study reported here, the sample consists of 48 patients of legal age seen from the beginning of the epidemic with a diagnosis of coronavirus infection or suspected infection until the date on which the field study was initiated, 30 April 2020. It was decided to no longer include patients after this date, as the living conditions were qualitatively different (lockdown) and could lead to a bias between those interviewed and affected before and after this date.

A psychological symptomatology (BSI-18) screening questionnaire was conducted by telephone.

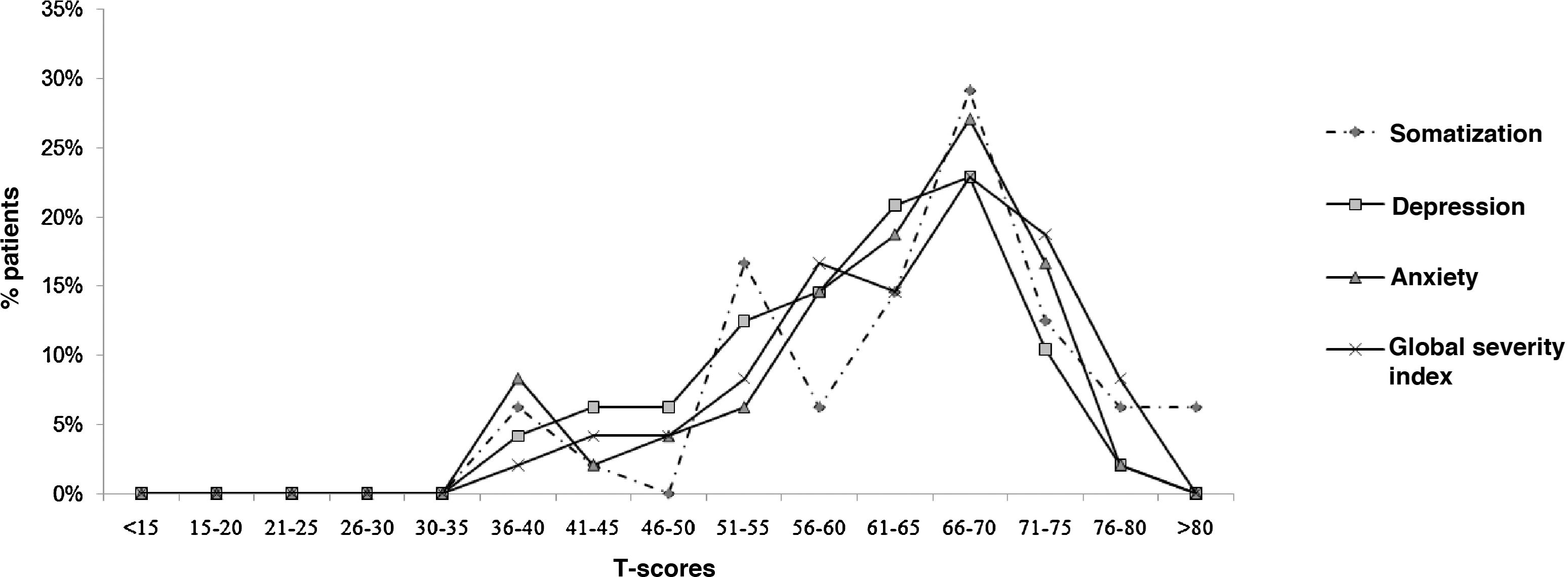

With respect to the results of the interviews, Fig. 1 shows the T-scores on the different scales of the BSI-18 of the sample analysed. T-scores are a standardised scale with a mean value of 50 (SD = 10). However, we found that the means of the patients in all the scales were close to T = 60 (corresponding to an 84th percentile), with the differences being statistically significant for all the scales (somatization: X = 63.68 (SD = 10.51) t = 9.022 p < 0.000; depression: X = 60.54 (SD = 9.90) t = 7.376 p < 0.000; anxiety: X = 62.10 (SD = 8.47) t = 8.471 p < 0.000; global severity index (GSI): X = 63.40 (SD = 9.74) t = 9.532 p < 0.000).

Observing the specific items answered, the most common symptoms were "feeling blue" (X = 2.18); "feeling fearful" (X = 1.97) and "feeling tense or keyed up" (X = 2.06). On the other hand, the least common were "thoughts of ending your life" (X = 0.10), "spells of terror or panic" (X = 0.52) and "suddenly scared for no reason" (X = 1.04). The most recurrent symptoms are those related to mild anxiety-depressive symptoms, that is, symptoms that are more to be expected shortly after a stressful situation such as the one they have experienced. In contrast, the more severe symptoms (suicidal ideation, panic attacks and post-traumatic symptoms) are less recurrent. This may indicate that, as a result of this situation, patients experience the expected symptoms following the events they have lived through (pandemic, lockdown, etc.) or that psychological symptoms are beginning to appear and, over time, may worsen and/or become chronic.

Finally, as the BSI-18 is a screening questionnaire, it offers a cut-off point to determine if the patient is a possible clinical case (T > 63 on the GSI or T > 63 on two of the scales). In this sample, 62.5% of the people are a possible clinical case (n = 30), which shows, once again, that these patients are experiencing psychological symptoms derived from this situation. As a complement to this information, it was observed that, during the interview, when offering them some type of free psychological support, 47.9% (n = 23) requested it.

We conclude that the symptoms of the patients were varied (anxiety, depression, and somatization) and significantly higher than the population average, which could be the subject of clinical attention. Although the symptoms were mild, it could be due to the proximity of the stressful event or merely as a coping mechanism. These results are consistent with previous studies conducted with both, patients with the SARS2–4 back in 2003, as well as those with COVID-191,5.

It is important to establish support mechanisms and resources for those who may require them. We can draw on similar situations in the past, such as the SARS epidemic of 20034. Future research should assess how this symptomatology evolves over time, whether it is maintained or resolved, and a second analysis in the following months would provide useful information for such a comparison.

FundingNo funding has been received for the preparation of this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors of this document declare the absence of any conflict of interest related to the publication of this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Peral Martín A, Cabezas García M, Martínez Sáez Ó. Estado y gestión emocional de los pacientes afectados por la COVID-19 en un centro de salud. Med Clin (Barc). 2021;156:248–249.