The objective was to describe the clinical characteristics and prognosis of patients with nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection.

MethodsAn observational and prospective study was performed in a referral hospital. We included all adult patients diagnosed with nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection in October 2020. Nosocomial infection was defined as a negative PCR for SARS-CoV-2 on admission and a positive PCR after 7 days of hospitalization.

ResultsWe included 66 cases of nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection: 39 (59%) men, median age at diagnosis was 74.5 years (IQR 56.8–83.1) and median Charlson comorbidity index was 3 points (IQR 1–5). Twenty-seven (41%) developed pneumonia and 13 (20%) died during admission. Mortality at 28 days was 33% (22 patients). Mortality at 28 days in the 242 patients with community-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection who were hospitalized during the same period was 10%.

ConclusionsPreventive measures and early detection of nosocomial outbreaks of COVID-19 should be prioritized to minimize the negative impact of this infection.

El objetivo fue describir las características clínicas y el pronóstico de los pacientes con infección nosocomial por SARS-CoV-2.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio observacional y prospectivo en un hospital de referencia. Se incluyeron todos los pacientes adultos diagnosticados de infección por SARS-CoV-2 nosocomial en octubre de 2020, definida como una PCR para SARS-CoV-2 negativa al ingreso y positiva a partir de los siete días de hospitalización.

ResultadosSe diagnosticaron 66 casos de infección por SARS-CoV-2 nosocomial: 39 (59%) hombres, edad mediana al diagnóstico de 74,5 años (RIC 56,8-83,1) y mediana del índice de comorbilidad de Charlson de 3 puntos (RIC 1−5). Veintisiete (41%) presentaron neumonía y 13 (20%) fallecieron durante el ingreso. La mortalidad a los 28 días fue del 33% (22 pacientes). La mortalidad a los 28 días en los 242 pacientes con infección por SARS-CoV-2 adquirida en la comunidad y hospitalizados durante el mismo periodo fue del 10%.

ConclusionesSe deben extremar las medidas de prevención y detección precoz de brotes nosocomiales de COVID-19 para minimizar el impacto negativo de esta infección.

The second wave of COVID-19 in Barcelona was characterised by a gradual increase in hospital admissions1, due, among others, to early diagnosis, improved contact tracing and various restrictive measures. Even in this situation, the hospitals maintained their usual activity. However, the close coexistence of inpatients with and without SARS-CoV-2 infection, as well as the circulation of the virus in the community and the absence of vaccination, led to the emergence of nosocomial cases. Another possible risk factor was visits by patients' relatives, which were generally suspended in mid-October due to an increase in nosocomial COVID-19 episodes.

A number of studies have analysed the clinical features and prognosis after hospital admission of patients with community-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection2 and outbreaks in healthcare workers3 have also been described, but few studies describing the progression of patients with nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection are available4–8.

The objective of this study was to describe the clinical features and prognosis of patients with nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection.

MethodsAn observational and prospective study was carried out at the Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron (Barcelona), a tertiary hospital with 1000 beds, with all medical and surgical departments.

As per protocol, real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs was performed on all adult patients requiring hospital admission as of August 20209. In case of close contact with a confirmed case of SARS-CoV-2 infection, in case of an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 in an inpatient unit and in case of clinical suspicion of infection, the test is repeated prior to any invasive test or transfer to another facility. The Preventive Medicine and Infectious Diseases Departments identify patients with a positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2 on a daily basis and carry out the corresponding epidemiological screening.

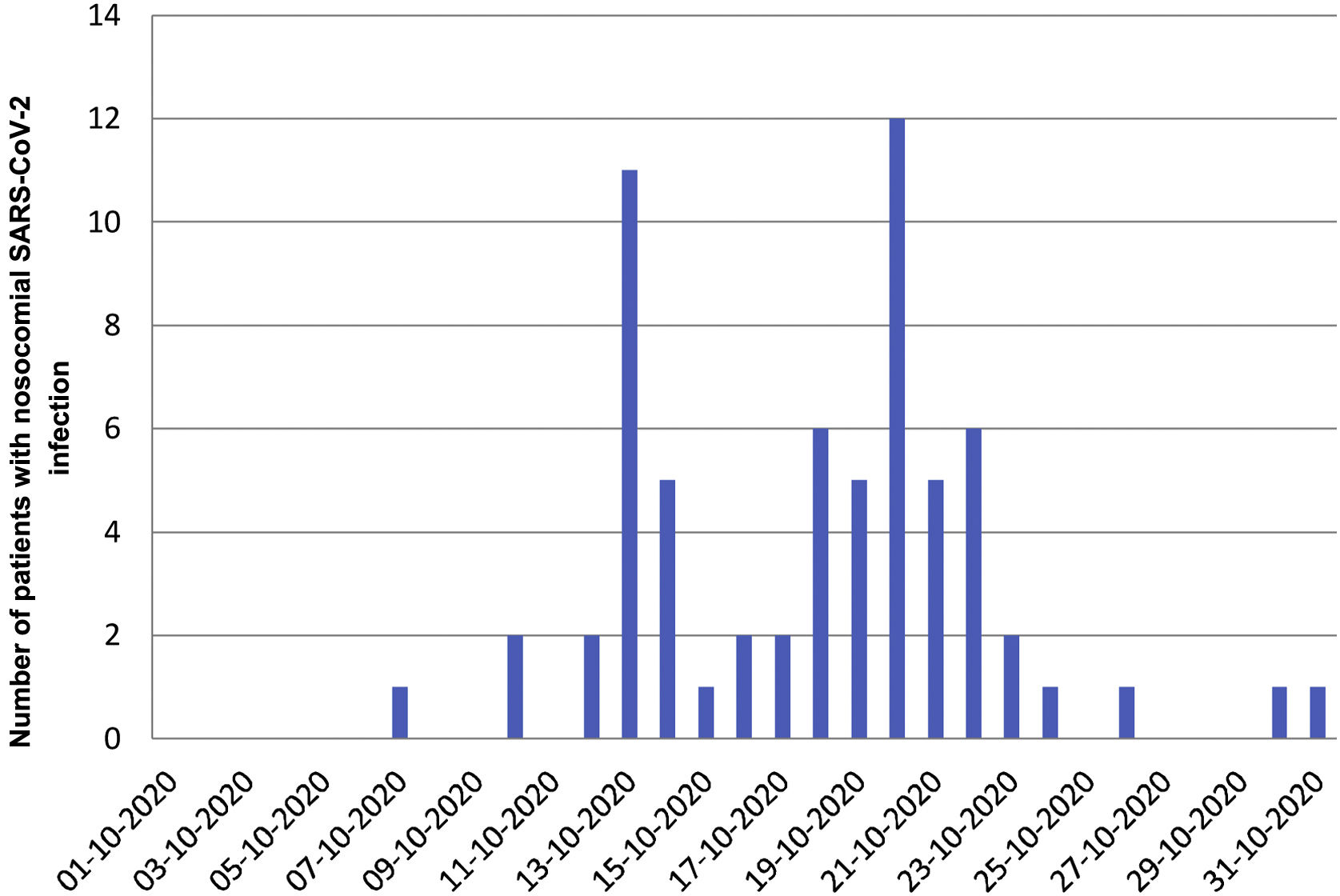

All adult patients diagnosed with nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection between 1 and 31 October 2020, the period in which a nosocomial outbreak occurred in our centre, were prospectively included (Fig. 1). Nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection was defined as a negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR on admission (or <48 h earlier, in case of planned admissions) and a positive PCR 7 days after admission. Patients with a positive PCR during the first seven days after admission or after discharge were excluded as it was not possible to differentiate between community-acquired and nosocomial infection. Patients were monitored for 28 days after diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The primary endpoint was overall mortality 28 days after diagnosis, and the secondary endpoints were hospital mortality, the presence of pneumonia, and respiratory failure. Clinical characteristics were also compared between patients with nosocomial COVID-19 who survived and those who died using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test (Mann-Whitney) for continuous variables.

ResultsWe identified 66 patients with nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection: 39 (59%) were men and the median age at diagnosis was 74.5 years (interquartile range [IQR] 56.8–83.1). The median Charlson comorbidity index was 3 points (IQR 1−5) and the most common comorbidities were hypertension (42, 64%), chronic kidney disease (23, 35%), diabetes (20, 30 %), neoplasm (17, 26%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (14, 21%), immunosuppressive treatment (10, 15%, including 4 kidney transplants), ischemic heart disease (9, 14%) and cerebrovascular disease (9, 14%). Fifty-three (80%) were diagnosed during admission to a medical area, 10 (15%) to a surgical area, and 3 (5%) to an intensive care unit (ICU).

The median number of days from admission to diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection was 12 (IQR 8–19). The reasons for performing the test were close contact with a confirmed case of SARS-CoV-2 infection in 18 (27%) cases, screening in asymptomatic patients in the context of an outbreak in the hospitalization unit in 18 (27%) cases, suspected clinical signs of SARS-CoV-2 infection in 17 (26%) cases, work-up prior to performing an invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedure in 8 (12%) cases and prior to transfer to another site in 5 (8%) cases.

Thirty-eight (58%) patients showed some symptoms (fever in 32, dyspnoea in 14, and cough in 6) and 28 (42%) remained asymptomatic during admission. Twenty-seven (41%) patients developed pneumonia a median of 1.5 (IQR 1–4.5) days after diagnosis, and of these, 25 (93%) developed respiratory failure after a median of 4 (IQR 2−5) days. Seven patients required oxygen therapy with high-flow nasal cannulas, two non-invasive mechanical ventilation and one invasive mechanical ventilation.

The median hospital stay was 21 (IQR 14–35) days. Hospital mortality was 20% (13 patients), a median of 10 (IQR 6–12) days after diagnosis and mortality at 28 days was 33% (22 patients). Table 1 compares the clinical characteristics of patients who survived to discharge with those who died.

Comorbidities and clinical features of patients with nosocomial COVID-19 who survived and died at discharge (N = 62a).

| Survivors | Deceased | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 49 | N = 13 | ||

| Arterial hypertension | 29 (59%) | 12 (92%) | 0.045 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14 (29%) | 6 (46%) | 0.318 |

| Neoplasm | 12 (24%) | 4 (31%) | 0.725 |

| COPD | 10 (20%) | 4 (31%) | 0.466 |

| Immunosuppression | 6 (12%) | 4 (31%) | 0.196 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (interquartile range) | 2 (1–5) | 3 (2–5) | 0.553 |

| Asymptomatic | 22 (45%) | 13 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 12 (24%) | 11 (85%) | <0.001 |

COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

During the same period, 242 patients with community-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection were admitted (PCR for SARS-CoV-2 positive at admission), with a median age at diagnosis of 55.4 (IQR 43.9–68.3) years and an overall hospital mortality and 28 days after diagnosis of 9% and 10%, respectively.

DiscussionSixty-six cases of nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection were diagnosed during the month of October 2020 in a referral hospital, most commonly in elderly males with comorbidities. Forty-one percent developed pneumonia very early after diagnosis, mostly associated with respiratory failure, and 20% died during admission, with a 28-day mortality of 33%.

The high mortality of patients with nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection in our study is consistent with that of a multicentre study in solid organ transplant patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in which nosocomial acquisition was a risk factor for mortality in the univariate analysis (OR: 3.0, 95% CI: 1.9–4.9)10. Another study conducted during the first wave of COVID-19 in London described a high mortality (36%) in cases of nosocomial COVID-19 after a minimum follow-up of three weeks6. In contrast, another multicenter study conducted in Scotland also during the first wave found no statistically significant differences in overall mortality at 30 days between patients with nosocomial and community infection (21.1% vs. 17.6%)4. However, no PCR was systematically performed on admission.

In our center, mortality was higher in the group of patients with nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection, despite the fact that the treatment protocol was the same for all patients. Although we do not have all the clinical variables to compare the two groups, as this was not the aim of the study, we believe that mortality was higher in the nosocomial infection group because the patients were older (and presumably had more comorbidities).

This study has several limitations: 1) the variability of the incubation period in this infection may have led to a selection bias of patients with nosocomial infection; 2) we did not compare all clinical characteristics and prognosis with community-acquired SARS-CoV-2 patients because we did not have all the variables involved (only mortality and age). However, a notable strength is that all patients with infection regarded as nosocomial had a negative PCR on admission.

Thanks to active contact and staff screening, isolation of close contacts and cohorting of patients with nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection, the outbreak was brought under control by the end of October (Fig. 1).

ConclusionsNosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection is, potentially, a very serious condition, which rapidly progresses with the onset of pneumonia and respiratory failure. Preventive measures and early detection of nosocomial COVID-19 outbreaks should be maximised so as to minimise the negative impact of this infection.

We would like to thank the associate investigators of this study: Magda Campins (Preventive Medicine Department, Vall d'Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain) and Benito Almirante (Infectious Diseases Department, Vall d'Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain).