Smoking can play a key role in SARS-CoV-2 infection and in the course of the disease. Previous studies have conflicting or inconclusive results on the prevalence of smoking and the severity of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19).

MethodsObservational, multicenter, retrospective cohort study of 14,260 patients admitted for COVID-19 in Spanish hospitals between February and September 2020. Their clinical characteristics were recorded and the patients were classified into a smoking group (active or former smokers) or a non-smoking group (never smokers). The patients were followed up to one month after discharge. Differences between groups were analysed. A multivariate logistic regression and Kapplan Meier curves analysed the relationship between smoking and in-hospital mortality.

ResultsThe median age was 68.6 (55.8−79.1) years, with 57.7% of males. Smoking patients were older (69.9 (59.6−78.0 years)), more frequently male (80.3%) and with higher Charlson index (4 (2−6)) than non-smoking patients. Smoking patients presented a worse evolution, with a higher rate of admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) (10.4 vs. 8.1%), higher in-hospital mortality (22.5 vs. 16.4%) and readmission at one month (5.8 vs. 4.0%) than in non-smoking patients. After multivariate analysis, smoking remained associated with these events.

ConclusionsActive or past smoking is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients with COVID-19. It is associated with higher ICU admissions and in-hospital mortality.

El tabaquismo puede tener un papel importante en la infección por SARS-CoV-2 y en el curso de la enfermedad. Los estudios previos muestran resultados contradictorios o no concluyentes sobre la prevalencia de fumar y la severidad en la enfermedad por coronavirus (COVID-19).

Material y métodosEstudio de cohortes observacional, multicéntrico y retrospectivo de 14.260 pacientes que ingresaron por COVID-19 en hospitales españoles desde febrero a septiembre de 2020. Se registraron sus características clínicas y se clasificaron en el grupo con tabaquismo si tabaquismo activo o previo o en el grupo sin tabaquismo si nunca habían fumado. Se realizó un seguimiento hasta un mes después del alta. Se analizaron las diferencias entre grupos. La relación entre tabaquismo y mortalidad intrahospitalaria se valoró mediante una regresión logística multivariante y curvas de Kapplan Meier.

ResultadosLa mediana de edad fue 68,6 (55,8–79,1) años, con un 57,7% de varones. El grupo con tabaquismo presentó mayor edad (69,9 (59,6–78,0 años)), predominio masculino (80,3%) y mayor índice de Charlson (4 (2−6)). La evolución fue peor en estos pacientes, con una mayor tasa de ingreso en UCI (10,4 vs 8,1%), mayor mortalidad intrahospitalaria (22,5 vs 16,4%) y reingreso al mes (5,8 vs 4,0%) que el grupo sin tabaquismo. Tras el análisis multivariante, el tabaquismo permanecía asociado a estos eventos.

ConclusionesEl tabaquismo de forma activa o pasada es un factor predictor independiente de mal pronóstico en los pacientes con COVID-19, estando asociada a mayor probabilidad de ingreso en UCI y a mayor mortalidad intrahospitalaria.

On 11th March 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared a coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), the aetiological agent of which was SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2). Previous studies have shown that the incidence of severe disease is higher in men, in people over 65 years of age and in those with chronic health conditions, mainly diabetes and obesity1, which leads to a longer average hospital stay and an increased risk of death2,3. Research into the factors that may influence the prognosis of the disease is essential to better understand the progression of patients and to establish strategies for their management, aiming to improve their survival.

One of the factors that has been studied is smoking. Smoking increases the risk of infections in general, both bacterial and viral4, and causes inflammation of the respiratory tract mucosa through the release of inflammatory mediators such as IL-8 or IL-1β5. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 penetrates through the mucous membranes and invades the respiratory tract, reaching the lung through receptors. One of these receptors is the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor, which is most frequently expressed in alveolar macrophages and type 2 pneumocytes in the alveoli of smokers6. There appears to be a direct correlation between smoking, time of exposure to tobacco smoke and ACE-2 receptor expression. This implies that the longer smokers are exposed to tobacco smoke, the greater the number of receptors in their membranes and, therefore, the greater the risk of coronavirus lung infection7,8. In addition, binding to these receptors will control the release of ACE, which seems to play a key role in the inflammatory response of COVID-199. Therefore, smoking may play a key role in SARS-CoV-2 infection and the course of the disease. However, previous studies have contradictory or inconclusive results in relation to the prevalence of smoking and COVID-19, they are not designed to understand the impact that tobacco causes on COVID-19, and the available data come from mainly Asian studies6,10.

The objective of this study was to analyse the possible association of smoking with higher in-hospital mortality from all causes in patients with COVID-19 in Spain.

The secondary objectives were: 1) study the progression of the disease, complications and admission to Intensive Care (ICU) during hospitalization and events at 30 days (mortality or readmission), 2) analyse the differences between active smokers and former smokers.

MethodsPatientsPatient data were collected from the SEMI-COVID-19 Registry, a national observational, multicentre, retrospective cohort study of 132 Spanish hospitals, presently recruiting. Inclusion criteria were age over 18, first hospital admission from February to September 2020 with a diagnosis of COVID-19, with microbiological confirmation by RT-PCR (reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction) of nasopharyngeal, sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage swab specimens. Patients were excluded if the variable "smoking" was not collected, if they were re-admitted or if they did not wish to participate after informed consent.

VariablesRegistry information was available in the study published by Casas-Rojo et al.12, which included the procedures and described the baseline characteristics of the patients in the registry. Some 300 variables were retrospectively collected, including epidemiological data, medical history (including smoking history), previous medications, symptoms and physical examination findings on admission, and laboratory and radiological imaging data on admission and 7 days after admission, or prior to ICU admission, as well as pharmacological treatment, ventilatory support and complications during hospitalization and progression during the first month after discharge.

Patients were classified by smoking history into two groups: "smoking group" with those active smokers or former smokers and as "non-smoking group" with those who had never smoked.

The qSOFA index (quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score) based on respiratory rate, systolic pressure and state of consciousness, and the Charlson index according to previous comorbidities. History of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation were grouped as cardiovascular disease.

Disease progression during hospitalization was considered to be the combined event of death, mechanical ventilation, and/or admission to the ICU. Regarding complications during admission, acute respiratory distress syndrome, bacterial pneumonia, sepsis/multiple organ failure/shock, heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, renal failure, stroke, and venous thromboembolism were considered.

Ethical aspectsThe study protocol was approved by the Provincial Research Ethics Committee of Malaga (Spain) following the recommendations of the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS). The STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) recommendations for the design of observational cohort studies were followed. All patients provided their informed consent. When written consent was not possible for biosafety reasons or if the patient had already been discharged, informed consent was given verbally and recorded in the medical record.

Statistical analysisThe results of the variables were expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) according to the normal distribution criteria evaluated with the Kolmogorov Smirnov test. Continuous variables were compared using the Student t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and were compared using the χ2 test. A multivariate logistic regression was used to evaluate the relationship between smoking and in-hospital mortality. The variables considered possible confounding or modifying factors were age, sex, Charlson index adjusted for age, degree of moderate-severe dependence, alcohol consumption, smoking, obesity, moderate-severe chronic renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS), cancer and cardiovascular disease. The analysis was carried out using backward stepwise regression. In-hospital mortality in the first 100 days was also analysed using Kaplan Meier curves (with log-rank). Similarly, for the analysis of the influence of smoking on the secondary objectives of disease progression, complications, admission to the ICU and mortality or readmission at one month, a multivariate analysis was performed with the same variables, changing the result variable.

For the analysis of active smokers vs. former smokers, a univariate comparison was made using the χ2 test.

A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The SPSS version 25.0 statistical software (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used.

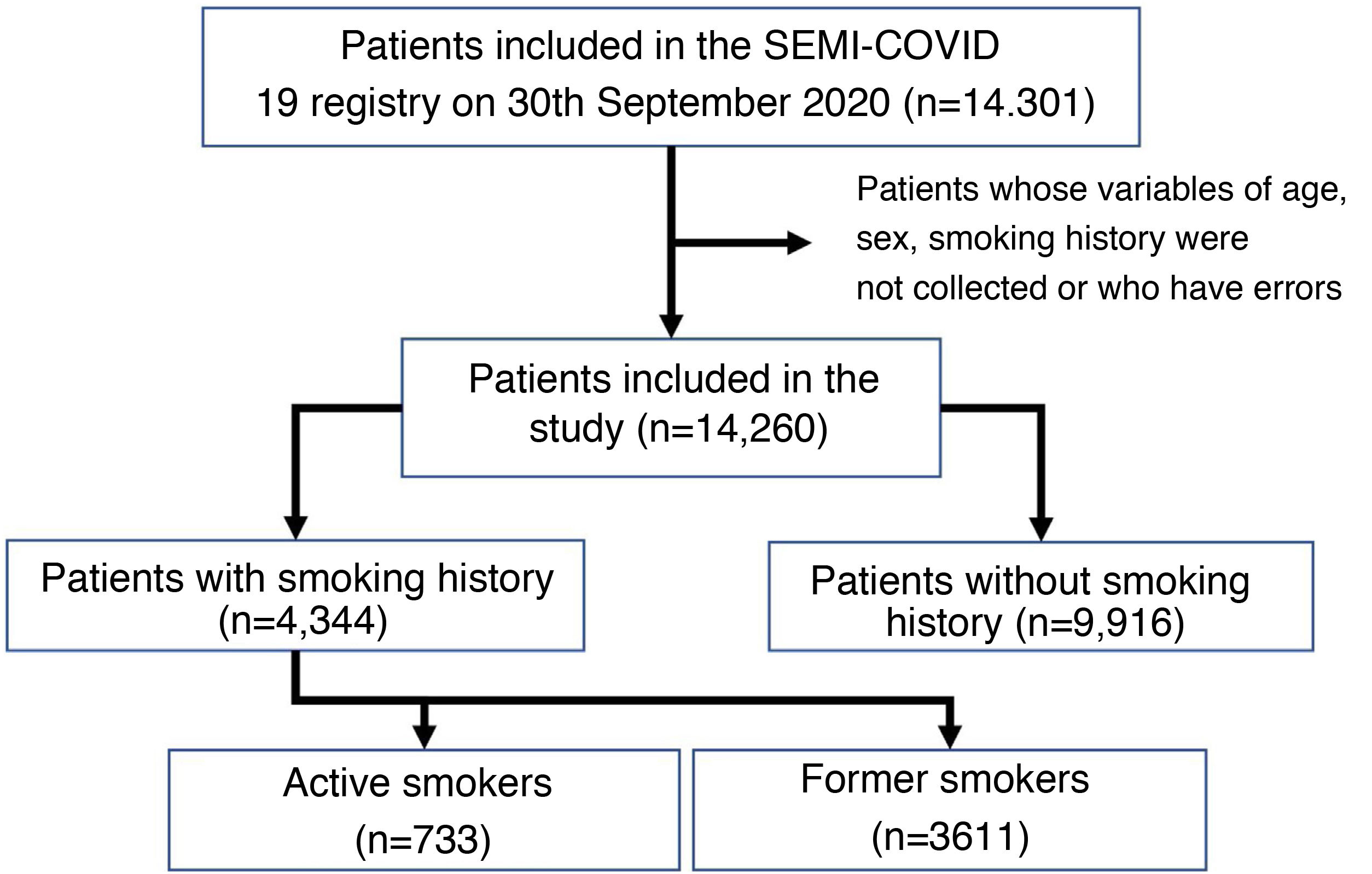

ResultsBaseline patient characteristicsAs of 30th September 2020, the SEMI-COVID-19 registry included 14,301 patients, of whom 14,260 met the inclusion criteria for our analysis (see Fig. 1). Characteristics are shown in Table 1, with a mean age of 68.6 (55.8−79.1), 57.7% male and a hospital stay of 9 days (5−14 days). The smoking group was significantly older, predominantly male, and had more cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities than the non-smoking group (Table 1).

Patient demographics and co-morbidities according to smoking history.

| Total (n = 14.260) | Non-smoking group(n = 9.916) | Smoking group(n = 4.344) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.6 (55.8−79.1) | 67.8 (53.8−79.6) | 69.9 (59.6−78.0) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 8.221 (57.7) | 4.732 (47.7) | 3.489 (80.3) | <0.001 |

| Days of hospitalization | 9 (5−14) | 8 (5−13) | 9 (6−15) | <0.001 |

| Age-Adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index | 3 (1−5) | 3 (1−5) | 4 (2−6) | <0.001 |

| Degree of dependency (moderate-severe) | 2.179 (15.4) | 1.585 (16.1) | 594 (13.8) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 652 (4.6) | 177 (1.8) | 475 (11.1) | <0.001 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 2.904 (21.9) | 1.864 (20.2) | 1.040 (25.6) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 7.180 (50.4) | 4.690 (47.3) | 2.490 (57.4) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 5.575 (39.1) | 3.514 (35.5) | 2.061 (47.5) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.764 (19.4) | 1.729 (17.5) | 1.035 (23.8) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety Depression | 1993 (14.0) | 1.443 (14.4) | 570 (13.2) | 0.053 |

| Malignant disease (solid tumour, leukaemia, lymphoma) | 1.459 (10.3) | 833 (8.4) | 626 (14.4) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, heart failure, atrial fibrillation) | 2.691 (18.9) | 1.529 (15.5) | 1.162 (26.8) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 93 (0.7) | 62 (0.6) | 31 (0.7) | 0.545 |

| COPD/chronic bronchitis | 1.314 (9.2) | 301 (3.0) | 1.013 (23.3) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 1.026 (7.2) | 735 (7.4) | 291 (6.7) | 0.134 |

| Obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnea syndrome | 862 (6.1) | 401 (4.1) | 461 (10.7) | <0.001 |

| Moderate-severe kidney disease | 851 (6.0) | 515 (5.2) | 336 (7.7) | <0.001 |

Data are expressed as median (25th percentile–75th percentile) for quantitative variables and as frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables.

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BMI: body mass index.

With regard to their symptoms (Table 2), dyspnoea was more common in patients with smoking and fever and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients without smoking. In addition, patients with smoking were admitted with an elevated qSOFA index (≥2) and oxygen saturation <90% in a higher percentage than patients without smoking (9.9 vs. 8.5% and 33.9 vs. 31.0%, p < 0.01, respectively), while in the latter radiological lung involvement was more common. Patients with smoking also had a higher percentage of poor prognostic laboratory parameters, with lymphopenia 42.6 vs. 37.7% and high levels of CRP (52.2 vs. 49.9%), ferritin (50.6 vs. 45.5%), D-dimer (33.9 vs. 31.3%) and LDH (33.0 vs. 29.7%), p < 0.01.

Patients' clinical presentation, examination, and laboratory and imaging findings according to smoking history.

| Total(n = 14.260) | Non-smoking group(n = 9.916) | Smoking group(n = 4.344) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical presentation | ||||

| Fever | 12.008 (84.4) | 8.398 (84.9) | 3.610 (83.2) | 0.009 |

| Cough | 1.0471 (73.5) | 7.262 (73.3) | 3.209 (73.9) | 0.423 |

| Odynophagia | 1.400 (9.9) | 981 (9.9) | 419 (9.7) | 0.667 |

| Dyspnoea | 8.223 (57.8) | 5.615 (56.7) | 2.608 (60.1) | <0.001 |

| Diarrhoea | 3.467 (24.4) | 2.482 (25.1) | 985 (22.7) | 0.003 |

| Nausea | 1.769 (12.5) | 1.324 (13.5) | 445 (10.3) | <0.001 |

| Vomiting | 1.134 (8.0) | 859 (8.7) | 275 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 950 (6.7) | 695 (7.0) | 255 (5.9) | 0.013 |

| Physical examination and laboratory and imaging findings | ||||

| qSOFA ≥ 2 | 1.218 (9.0) | 804 (8.5) | 414 (9.9) | 0.008 |

| Oxygen saturation (pulse oximetry) (<90%) or oxygen therapy | 4.403 (32.9) | 2.897 (31.0) | 1.506 (32.9) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary infiltrates | 12.348 (87.2) | 8.628 (87.6) | 3.720 (86.2) | 0.017 |

| Total lymphocytes (×106/L) | 940 (690−1.300) | 971 (700−1.300) | 975 (640−1270) | <0.001 |

| Total lymphocytes <800 × 106/L | 5.557 (39.2) | 3.717 (37.7) | 1.840 (42.6) | <0.001 |

| LDH (U/L) | 321 (247−433) | 320 (247−426) | 327 (246−447) | 0.011 |

| LDH > 400 U/L | 3.841 (30.7) | 2.573 (29.7) | 1.268 (33.0) | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 61 (20−128) | 59 (20−125) | 65 (21−137) | 0.001 |

| CRP > 60 mg/L | 6.824 (50.0) | 4.650 (49.0) | 2.174 (52.2) | 0.001 |

| Serum ferritin (mcg/L) | 612 (287−1.232) | 583 (279−1.193.5) | 671 (307−1.302) | <0.001 |

| Serum ferritin > 650mcg/L | 2.809 (47.1) | 1.869 (45.5) | 950 (50.6) | <0.001 |

| D-dimer (ng/mL) | 662 (371−1241) | 640 (363−1220) | 700 (400−1.290) | <0.001 |

| D-dimer > 1.000 ng/mL | 3.661 (32.1) | 2.497 (31.3) | 1.164 (33.9) | 0.007 |

Data are expressed as median (25th percentile–75th percentile) for continuous variables and as frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables.

CRP: C-reactive protein; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; qSOFA: quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score.

Overall, 8.8% required admission to the ICU, with a higher frequency in the smoking group (10.4% vs. 8.1%, p < 0.001). The need for non-invasive or invasive mechanical ventilation was also higher in the smoking group (6.5 vs. 4.5% and 8.0 vs. 6.6%, p < 0.001, respectively). In addition, these also received empirical antibiotic therapy (91.0 vs. 88.6, p < 0.001) and immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory treatments in higher percentages, such as corticosteroids in 41.0% of the smoking group vs. 33.8% of the non-smoking group, p < 0.001 (Table 3).

Disease progression and events 30 days after discharge according to smoking history.

| Total(n = 14.260) | Non-smoking group(n = 9.916) | Smoking group(n = 4.344) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | 1.251 (8.8) | 801 (8.1) | 450 (10.4) | <0.001 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 999 (7.0) | 650 (6.6) | 349 (8.0) | 0.001 |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 734 (5.1) | 450 (4.5) | 284 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| Immunomodulatory treatment | 5.433 (43.2) | 3.574 (41.0) | 1.859 (48.1) | <0.001 |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 5.117 (36.0) | 3.341 (33.8) | 1.776 (41.0) | <0.001 |

| Tocilizumab | 1.301 (9.1) | 871 (8.8) | 430 (9.9) | 0.032 |

| Antibiotic treatment | 12.721 (89.3) | 8.776 (88.6) | 3.945 (91.0) | <0.001 |

| Complications during admission | 6.620 (46.4) | 4.341 (43.8) | 2.279 (52.5) | <0.001 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | ||||

| No | 9.501 (66.8) | 6.827 (69.0) | 2.674 (61.7) | <0.001 |

| Mild | 1.289 (9.1) | 877 (8.9) | 412 (9.5) | |

| Moderate | 1.106 (7.8) | 718 (7.3) | 388 (9.0) | |

| Severe | 2.336 (16.4) | 1.477 (14.9) | 859 (19.8) | |

| Bacterial pneumonia | 1.558 (10.9) | 986 (9.9) | 572 (13.2) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 871 (6.1) | 550 (5.5) | 321 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 335 (2.4) | 211 (2.1) | 124 (2.9) | 0.008 |

| In-hospital mortality | 2.609 (18.3) | 1.631 (16.4) | 978 (22.5) | <0.001 |

| radiological worsening | 4.277 (38.4) | 2.788 (36.5) | 1.489 (42.6) | <0.001 |

| Disease progression | 3.595 (25.2) | 2.285 (23.0) | 1.310 (30.2) | <0.001 |

| Events 30 days after discharge | ||||

| Readmission at 30 days | 526 (4.5) | 332 (4.0) | 194 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Mortality at 30 days | 158 (1.4) | 106 (1.3) | 52 (1.5) | 0.262 |

Data are expressed as frequencies (percentages).

ICU: intensive care unit. Disease progression (ICU admission, non-invasive/invasive mechanical ventilation and/or in-hospital death).

The smoking group had more complications and mortality during admission than the non-smoking group (52.5% vs. 48.3% and 22.5% vs. 16.4%, respectively). Acute respiratory distress syndrome was the most common complication in both groups (with 28.8% moderate-severe distress in the smoking group vs. 22.2% in the non-smoking group).

Radiological worsening and disease progression also occurred more commonly in the smoking group than in the non-smoking group (42.6 vs. 36.5% and 30.2 vs. 23.0%, respectively).

At one-month post-discharge there were more readmissions in the smoking group, but the mortality rate was not higher.

In the subanalysis carried out to see the differences between smokers and former smokers, it was observed that the former smokers were older, with a higher percentage of men, Charlson comorbidity index and a moderate to severe degree of dependence. They also had more cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities (although there were no differences in respiratory diseases and renal failure). Clinical symptoms and laboratory parameters were similar, as were admissions to the ICU and the need for ventilation. However, former smokers required a higher percentage of immunomodulatory and antibiotic treatment and had more complications on admission such as in-hospital mortality (23.6 vs. 17.6%, p < 0.001), radiological worsening and disease progression, as well as readmissions (Appendix B Supplementary Tables 1–3).

A binary logistic regression was used to evaluate the factors that influenced in-hospital mortality, where the history of smoking (active or former) was an independent variable (OR 1.148 CI 95% 1.021−1.290, p = 0.021). In addition to smoking history, other independent variables for in-hospital mortality were age, male gender, age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index, moderate-severe degree of dependence, obesity, and cardiovascular disease (Table 4). Smoking was also an independent variable of ICU admission and readmissions at one month, but not of disease progression, complications during admission, or death at one month (Appendix B Supplementary Tables 4–8).

Binary logistic regression of in-hospital mortality from any cause.

| Independent variables | Coefficients | P | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.058 | 0.003 | 1.059 | 1.053−1.065 | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 0.532 | 0.059 | 1.702 | 1.516−1.911 | <0.001 |

| Age-Adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.137 | 0.013 | 1.147 | 1.117−1.177 | <0.001 |

| Degree of dependency (moderate-severe) | 0.497 | 0.066 | 1.644 | 1.446−1.869 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 0.138 | 0.059 | 1.148 | 1.021−1.290 | 0.021 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 0.267 | 0.061 | 1.305 | 1.157−1.472 | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, heart failure, atrial fibrillation) | 0.183 | 0.060 | 1.200 | 1.066−1.351 | 0.002 |

| Constant | −6.849 | 0.198 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

BMI: body mass index.

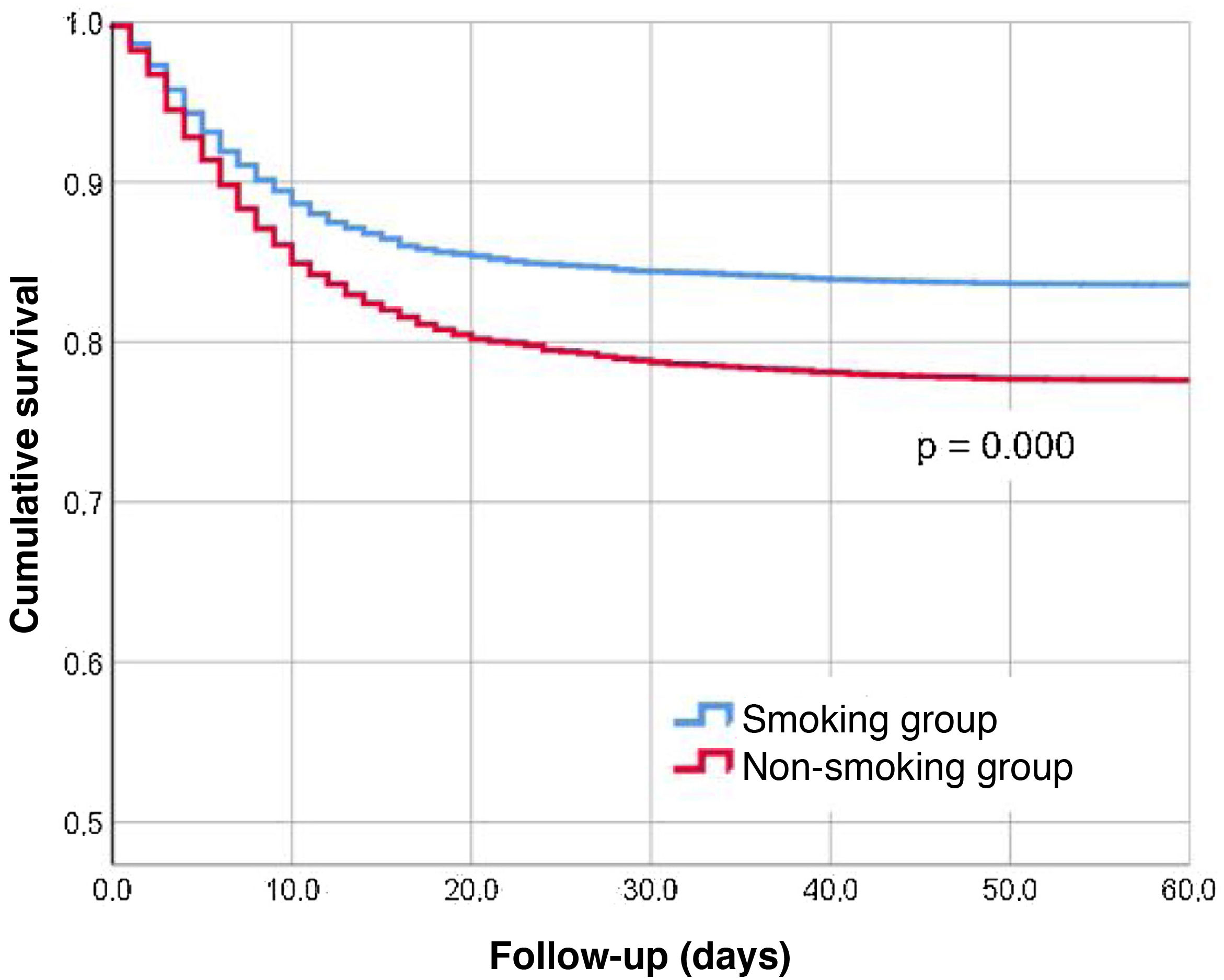

Fig. 2 shows the Kaplan Meier curves for in-hospital mortality in the first 100 days. It shows how patients in the smoking group died earlier than those in the non-smoking group.

DiscussionThis study analysed data from the SEMI-COVID-19 registry, currently the most extensive database available in Spain with patients admitted for COVID-19. The prevalence of smoking in Spain is high and the mortality attributed to its use in people over 35 years of age is also significant (12.9% of total mortality), mainly due to tumours, followed by cardiovascular and respiratory diseases11. In addition, COVID-19 also has both cardiovascular and pulmonary effects. This study assesses the association of smoking with mortality in patients with COVID-19. Smoking history was an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality. Thus, hospitalised COVID-19 patients with current or past smoking had a worse prognosis and higher mortality than those without.

In previous studies, the demographic characteristics of the patients overlapped ours, with advanced age, male prevalence, and presence of a greater number of comorbidities such as COPD or cardiovascular diseases6,9,13,14. Hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 has been found to be increased in precisely this type of patient (over 70 years of age, male and in relation to the number of associated diseases)1–3, so it is essential to study the effect that smoking may have. At present, the impact of smoking on the progression of COVID-19 remains controversial and studies so far are scarce.

Smoking is a risk factor for acquiring other bacterial and viral infections, including MERS-CoV-2 (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus), a situation we think could be extrapolated to COVID-196. Regardless of the effect of smoking on disease progression, the risk to which smokers are exposed for SARSCoV-2 infection is higher than in non-smokers6,15. However, this paper has not analysed whether smokers are at higher risk of acquiring the infection, only if the progression is different once they have been infected.

Pathophysiologically, cigarette smoke elicits an inflammatory response through activation of nuclear factor kappa, activated B-cell light chain enhancer, tumour necrosis factor-α, IL-1β and neutrophils5. It is known that patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection have elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines, so the sum of both would contribute to increased severity in COVID-1914. Previous meta-analyses have shown that being or having been a smoker increased the likelihood of severe disease progression6,9,16. The number of smokers has been found to be disproportionately higher among serious COVID-19 patients than among non-serious patients13,15–17. These results are similar to ours, where tobacco-exposed patients were admitted with a higher qSOFA and had acute respiratory distress syndrome more often and more severely, as well as a greater need for non-invasive mechanical ventilation or orotracheal intubation than non-exposed patients.

In disagreement with our findings, some investigators suggest a protective effect of smoking and nicotine on COVID-19, based on epidemiological studies where age and associated comorbidities have not been considered10. Even so, we must bear in mind that the cumulative risk of smoking to an individual's health outweighs the theoretical benefits14. Though data on the association between smoking and COVID-19 are confusing, the available scientific evidence suggests that smoking is associated with greater disease severity and mortality in these patients15,17.

In general, studies do not differentiate between current and former smokers. Smoking cessation improves lung function; however, this benefit is reduced among smokers who have been exposed for a long time due to accumulated lung injury over a prolonged period of time. Ex-smokers had a higher Charlson score and required more aggressive therapies than active smokers according to the sub-analysis. This could be due to a longer tobacco exposure, which has not been collected, which prevents a complete understanding of the impact of smoking on COVID-19 and has been identified as a limitation in most of the studies conducted13. Recently, two studies have assessed the cumulative effect of smoking, by pack-year and exposure time, suggesting cumulative exposure as an independent risk factor for hospital admission and death from SARS-CoV-2. The increase in cumulative smoking was associated with a higher number of admissions and deaths. This effect was greater in ex-smokers than in active smokers, in relation to older age and comorbidities18,19.

Just as the relationship between smoking and COVID-19 is unclear, so is the relationship between COPD and COVID-19. Zhao et al.13 conducted a meta-analysis showing that the risk of severity during COVID-19 is four times higher in COPD patients than in non-COPD patients. A two-fold increased risk was also found in patients with active smoking. It appears that COPD patients are not at increased risk of SARS-COV-2 infection but do have an increased mortality from COVID-19 compared to non-COPD patients (38.3% vs. 19.2%, p < 0.001). The prognosis during admission is even worse in COPD patients with associated comorbidities (hypertension, chronic kidney disease, cerebrovascular disease, etc.) than in COPD without comorbidities20.

Strengths of this study include the fact that the data come from a large registry with different hospital care levels, which makes their extrapolation to other populations easier. Previously, most of the published studies have been in Asian populations1,7,13,17. In addition, patients have been included at different chronological points in time and data have been obtained from medical records prepared by physicians.

In relation to limitations, this is a retrospective study in which we do not have an adequate smoking history: active/passive smoking, degree of exposure (packs/year), it does not discriminate between smoking devices (conventional cigarette, electronic cigarette, hookahs…) and neither the degree of exposure nor the time of smoking cessation was considered.

The inclusion of hospitalised patients makes it impossible to assess the risk of developing infection or requiring hospitalization. In addition, the design of the SEMI-COVID-19 registry generates the usual biases of observational studies (selection biases). The patients included have followed the hospital treatment and management protocol individualised to each health area, which may have been modified during the chronological development of the pandemic.

We are facing an unprecedented situation, with many areas of uncertainty, including the natural history of the disease. A prospective study with adequate data collection on smoking history would be useful in order to draw rigorous conclusions.

Given that our data suggest that patients exposed to tobacco have an unfavourable disease course with increased mortality and admission to the ICU, we believe smoking should be understood as a risk factor for poor outcome. Therefore, an adequate assessment of smoking history on admission could help us to design the management strategy for hospitalisedpatients.

ConclusionsSmoking, active or past, is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients with COVID-19, as it is associated with an increased likelihood of ICU admission and in-hospital mortality.

FundingThere is no research funding body and no grants have been received.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

AcknowledgementsWe wish to thank all the investigators participating in the SEMI-COVID-19 Registry.

APPENDIX. List of members of the SEMI-COVID-19 registrySEMI-COVID-19 Registry Coordinator: Jose Manuel Casas Rojo.

Members of the Scientific Committee of the SEMI-COVID-19 Registry: José Manuel Casas Rojo, José Manuel Ramos Rincón, Carlos Lumbreras Bermejo, Jesús Millán Núñez-Cortés, Juan Miguel Antón Santos, Ricardo Gómez Huelgas.

Members of the SEMI-COVID-19 Group

Bellvitge UH L'Hospitalet de Llobregat (Barcelona)

Xavier Corbella, Francesc Formiga Pérez, Narcís Homs, Abelardo Montero, Jose María Mora-Luján, Manuel Rubio-Rivas.

October UH Madrid

Paloma Agudo de Blas, Coral Arévalo Cañas, Blanca Ayuso, José Bascuñana Morejón, Samara Campos Escudero, María Carnevali Frías, Santiago Cossio Tejido, Borja de Miguel Campo, Carmen Díaz Pedroche, Raquel Diaz Simon, Ana García Reyne, Laura Ibarra Veganzones, Lucia Jorge Huerta, Antonio Lalueza Blanco, Jaime Laureiro Gonzalo, Jaime Lora-Tamayo, Carlos Lumbreras Bermejo, Guillermo Maestro de la Calle, Rodrigo Miranda Godoy, Barbara Otero Perpiña, Diana Paredes Ruiz, Marcos Sánchez Fernández, Javier Tejada Montes.

Costa del Sol H. Marbella (Malaga)

Victoria Augustín Bandera, Javier García Alegría, Nicolás Jiménez-García, Jairo Luque del Pino, María Dolores Martín Escalante, Francisco Navarro Romero, Victoria Nuñez Rodriguez, Julián Olalla Sierra.

Gregorio Marañon UH Madrid

Laura Abarca Casas, Álvaro Alejandre de Oña, Rubén Alonso Beato, Leyre Alonso Gonzalo, Jaime Alonso Muñoz, Christian Mario Amodeo Oblitas, Cristina Ausín García, Marta Bacete Cebrián, Jesús Baltasar Corral, Maria Barrientos Guerrero, Alejandro D. Bendala Estrada, María Calderón Moreno, Paula Carrascosa Fernández, Raquel Carrillo, Sabela Castañeda Pérez, Eva Cervilla Muñoz, Agustín Diego Chacón Moreno, Maria Carmen Cuenca Carvajal, Sergio de Santos, Andrés Enríquez Gómez, Eduardo Fernández Carracedo, María Mercedes Ferreiro-Mazón Jenaro, Francisco Galeano Valle, Alejandra Garcia, Irene Garcia Fernandez-Bravo, María Eugenia García Leoni, María Gómez Antúnez, Candela González San Narciso, Anthony Alexander Gurjian, Lorena Jiménez Ibáñez, Cristina Lavilla Olleros, Cristina Llamazares Mendo, Sara Luis García, Víctor Mato Jimeno, Clara Millán Nohales, Jesús Millán Núñez-Cortés, Sergio Moragón Ledesma, Antonio Muiño Míguez, Cecilia Muñoz Delgado, Lucía Ordieres Ortega, Susana Pardo Sánchez, Alejandro Parra Virto, María Teresa Pérez Sanz, Blanca Pinilla Llorente, Sandra Piqueras Ruiz, Guillermo Soria Fernández-Llamazares, María Toledano Macías, Neera Toledo Samaniego, Ana Torres do Rego, Maria Victoria Villalba Garcia, Gracia Villarreal, María Zurita Etayo.

Cabueñes H. Gijon (Asturias)

Ana María Álvarez Suárez, Carlos Delgado Vergés, Rosa Fernandez-Madera Martínez, Eva María Fonseca Aizpuru, Alejandro Gómez Carrasco, Cristina Helguera Amezua, Juan Francisco López Caleya, Diego López Martínez, María del Mar Martínez López, Aleida Martínez Zapico, Carmen Olabuenaga Iscar, Lucía Pérez Casado, María Luisa Taboada Martínez, Lara María Tamargo Chamorro.

Reg. Univ. H. of Malaga

María Mar Ayala-Gutiérrez, Rosa Bernal López, José Bueno Fonseca, Verónica Andrea Buonaiuto, Luis Francisco Caballero Martínez, Lidia Cobos Palacios, Clara Costo Muriel, Francis de Windt, Ana Teresa Fernandez-Truchaud Christophel, Paula García Ocaña, Ricardo Gómez Huelgas, Javier Gorospe García, José Antonio Hurtado Oliver, Sergio Jansen-Chaparro, Maria Dolores López-Carmona, Pablo López Quirantes, Almudena López Sampalo, Elizabeth Lorenzo-Hernández, Juan José Mancebo Sevilla, Jesica Martín Carmona, Luis Miguel Pérez-Belmonte, Iván Pérez de Pedro, Araceli Pineda-Cantero, Carlos Romero Gómez, Michele Ricci, Jaime Sanz Cánovas.

La Paz UH Madrid

Jorge Álvarez Troncoso, Francisco Arnalich Fernández, Francisco Blanco Quintana, Carmen Busca Arenzana, Sergio Carrasco Molina, Aranzazu Castellano Candalija, Germán Daroca Bengoa, Alejandro de Gea Grela, Alicia de Lorenzo Hernández, Alejandro Díez Vidal, Carmen Fernández Capitán, Maria Francisca García Iglesias, Borja González Muñoz, Carmen Rosario Herrero Gil, Juan María Herrero Martínez, Víctor Hontañón, Maria Jesús Jaras Hernández, Carlos Lahoz, Cristina Marcelo Calvo, Juan Carlos Martín Gutiérrez, Monica Martinez Prieto, Elena Martínez Robles, Araceli Menéndez Saldaña, Alberto Moreno Fernández, Jose Maria Mostaza Prieto, Ana Noblejas Mozo, Carlos Manuel Oñoro López, Esmeralda Palmier Peláez, Marina Palomar Pampyn, Maria Angustias Quesada Simón, Juan Carlos Ramos, Luis Ramos Ruperto, Aquilino Sánchez Purificación, Teresa Sancho Bueso, Raquel Sorriguieta Torre, Clara Itziar Soto Abanedes, Yeray Untoria Tabares, Marta Varas Mayoral, Julia Vásquez Manau.

Royo Villanova H. Zaragoza

Nicolás Alcalá Rivera, Anxela Crestelo Vieitez, Esther del Corral Beamonte, Jesús Díez Manglano, Isabel Fiteni Mera, Maria del Mar Garcia Andreu, Martin Gericó Aseguinolaza, Cristina Gallego Lezaun, Claudia Josa Laorden, Raul Martínez Murgui, Marta Teresa Matía Sanz.

Clinical Hospital of Santiago de Compostela (A Coruña)

Maria del Carmen Beceiro Abad, Maria Aurora Freire Romero, Sonia Molinos Castro, Emilio Manuel Paez Guillan, María Pazo Nuñez, Paula Maria Pesqueira Fontan.

San Carlos Clinic H. Madrid

Inés Armenteros Yeguas, Javier Azaña Gómez, Julia Barrado Cuchillo, Irene Burruezo López, Noemí Cabello Clotet, Alberto E. Calvo Elías, Elpidio Calvo Manuel, Carmen María Cano de Luque, Cynthia Chocron Benbunan, Laura Dans Vilan, Claudia Dorta Hernández, Ester Emilia Dubon Peralta, Vicente Estrada Pérez, Santiago Fernandez-Castelao, Marcos Oliver Fragiel Saavedra, José Luis García Klepzig, Maria del Rosario Iguarán Bermúdez, Esther Jaén Ferrer, Alejandro Maceín Rodríguez, Alejandro Marcelles de Pedro, Rubén Ángel Martín Sánchez, Manuel Méndez Bailón, Sara Miguel Álvarez, Maria José Nuñez Orantos, Carolina Olmos Mata, Eva Orviz García, David Oteo Mata, Cristina Outon González, Juncal Perez-Somarriba, Pablo Pérez Mateos, Maria Esther Ramos Muñoz, Xabier Rivas Regaira, Laura María Rodríguez Gallardo, Iñigo Sagastagoitia Fornie, Alejandro Salinas Botrán, Miguel Suárez Robles, Maddalena Elena Urbano, Andrea María Vellisca González, Miguel Villar Martínez.

Dr. Peset UH Valencia

Juan Alberto Aguilera Ayllón, Arturo Artero, María del Mar Carmona Martín, María José Fabiá Valls, Maria de Mar Fernández Garcés, Ana Belén Gómez Belda, Ian López Cruz, Manuel Madrazo López, Elisabeth Mateo Sanchis, Jaume Micó Gandia, Laura Piles Roger, Adela Maria Pina Belmonte, Alba Viana García.

Puerta de Hierro UH Madrid

María Álvarez Bello, Ane Andrés Eisenhofer, Ana Arias Milla, Isolina Baños Pérez, Laura Benítez Gutiérrez, Javier Bilbao Garay, Silvia Blanco Alonso, Jorge Calderón Parra, Alejandro Callejas Díaz, José María Camino Salvador, María Cruz Carreño Hernández, Valentín Cuervas-Mons Martínez, Sara de la Fuente Moral, Miguel del Pino Jimenez, Alberto Díaz de Santiago, Itziar Diego Yagüe, Ignacio Donate Velasco, Ana María Duca, Pedro Durán del Campo, Gabriela Escudero López, Esther Expósito Palomo, Ana Fernández Cruz, Esther Fiz Benito, Andrea Fraile López, Amy Galán Gómez, Sonia García Prieto, Claudia García Rodríguez-Maimón, Miguel Ángel García Viejo, Javier Gómez Irusta, Edith Vanessa Gutiérrez Abreu, Isabel Gutiérrez Martín, Ángela Gutiérrez Rojas, Andrea Gutiérrez Villanueva, Jesús Herráiz Jiménez, Pedro Laguna del Estal, María Carmen Máinez Sáiz, Cristina Martín, María Martínez Urbistondo, Fernando Martínez Vera, Susana Mellor Pita, Patricia Mills Sánchez, Esther Montero Hernández, Alberto Mora Vargas, Cristina Moreno López, Alfonso Ángel-Moreno Maroto, Victor Moreno-Torres, Concha, Ignacio Morrás De La Torre, Elena Múñez Rubio, Rosa Muñoz de Benito, Ana Muñoz Gómez, Alejandro Muñoz Serrano, Jose María Palau Fayós, Lina Marcela Parra Ramírez, Ilduara Pintos Pascual, Arturo José Ramos Martín-Vegue, Antonio Ramos Martínez, Isabel Redondo Cánovas del Castillo, Alberto Roldán Montaud, Lucía Romero Imaz, Yolanda Romero Pizarro, Enrique Sánchez Chica, David Sánchez Órtiz, Mónica Sánchez Santiuste, Patricia Serrano de la Fuente, Pablo Tutor de Ureta, Ángela Valencia Alijo, Mercedes Valentín-Pastrana Aguilar, Juan Antonio Vargas Núñez, Jose Manuel Vázquez Comendador, Gema Vázquez Contreras, Carmen Vizoso Gálvez.

Reina Sofía UH Cordoba

Antonio Pablo Arenas de Larriva, Pilar Calero Espinal, Javier Delgado Lista, Francisco Fuentes-Jiménez, María del Carmen Guerrero Martínez, María Jesús Gómez Vázquez, Jose Jiménez Torres, Laura Limia Pérez, José López-Miranda, Laura Martín Piedra, Marta Millán Orge, Javier Pascual Vinagre, Pablo Pérez-Martinez, María Elena Revelles Vílchez, Angela Rodrigo Martínez, Juan Luis Romero Cabrera, José David Torres-Peña.

Badajoz UH

Rafael Aragón Lara, Inmaculada Cimadevilla Fernandez, Juan Carlos Cira García, Gema Maria García, Julia Gonzalez Granados, Beatriz Guerrero Sánchez, Francisco Javier Monreal Periáñez, Maria Josefa Pascual Perez.

Moisès Broggi H. Sant Joan Despi (Barcelona)

Judit Aranda Lobo, Lucía Feria Casanovas, Jose Loureiro Amigo, Miguel Martín Fernández, Isabel Oriol Bermúdez, Melani Pestaña Fernández, Nicolas Rhyman, Nuria Vázquez Piqueras.

Rio Hortega UH Valladolid

Irene Arroyo Jiménez, Marina Cazorla González, Marta Cobos-Siles, Luis Corral-Gudino, Pablo Cubero-Morais, María González Fernández, José Pablo Miramontes González, Marina Prieto Dehesa, Pablo Sanz Espinosa.

San Juan UH of Alicante (Alicante)

Marisa Asensio Tomás, David Balaz, David Bonet Tur, Ruth Cañizares Navarro, Paloma Chazarra Pérez, Jesús Corbacho Redondo, Eliana Damonte White, María Escamilla Espínola, Leticia Espinosa Del Barrio, Pedro Jesús Esteve Atiénzar, Carles García Cervera, David Francisco García Núñez, Francisco Garrido Navarro, Vicente Giner Galvañ, Angie Gómez Uranga, Javier Guzmán Martínez, Isidro Hernández Isasi, Lourdes Lajara Villar, Verónica Martínez Sempere, Juan Manuel Núñez Cruz, Sergio Palacios Fernández, Juan Jorge Peris García, Rafael Piñol Pleguezuelos, Andrea Riaño Pérez, José Miguel Seguí Ripoll, Azucena Sempere Mira, Philip Wikman-Jorgensen.

Nuestra Señora del Prado H. Talavera de la Reina (Toledo)

Sonia Casallo Blanco, Jeffrey Oskar Magallanes Gamboa, Cristina Salazar Mosteiro, Andrea Silva Asiain.

Pozoblanco H. (Cordoba)

José Nicolás Alcalá Pedrajas, Antonia Márquez García, Inés Vargas.

UGH of Elda (Alicante)

Carmen Cortés Saavedra, Jennifer Fernández Gómez, Borja González López, María Soledad Hernández Garrido, Ana Isabel López Amorós, Santiago López Gil, Maria de los Reyes Pascual Pérez, Nuria Ramírez Perea, Andrea Torregrosa García.

Infanta Cristina UH Parla (Madrid)

Juan Miguel Antón Santos, Ana Belén Barbero Barrera, Blanca Beamonte Vela, Coralia Bueno Muiño, Charo Burón Fernández, Ruth Calderón Hernáiz, Irene Casado López, José Manuel Casas Rojo, Andrés Cortés Troncoso, Pilar Cubo Romano, Francesco Deodati, Alejandro Estrada Santiago, Gonzalo García Casasola Sánchez, Elena García Guijarro, Francisco Javier García Sánchez, Pilar García de la Torre, Mayte de Guzmán García-Monge, Davide Luordo, María Mateos González, José A. Melero Bermejo, Cruz Pastor Valverde, José Luis Pérez Quero, Fernando Roque Rojas, Lorea Roteta García, Elena Sierra Gonzalo, Francisco Javier Teigell Muñoz, Juan Vicente de la Sota, Javier Villanueva Martínez.

Santa Marina H. Bilbao

María Areses Manrique, Ainara Coduras Erdozain, Ane Labirua-Iturburu Ruiz.

San Pedro H. Logroño (La Rioja)

Diana Alegre González, Irene Ariño Pérez de Zabalza, Sergio Arnedo Hernández, Jorge Collado Sáenz, Beatriz Dendariena, Marta Gómez del Mazo, Iratxe Martínez de Narvajas Urra, Sara Martínez Hernández, Estela Menendez Fernández, Jose Luís Peña Somovilla, Elisa Rabadán Pejenaute.

Son Llàtzer UH Palma de Mallorca

Andrés de la Peña Fernández, Almudena Hernández Milián

Ourense UH

Raquel Fernández González, Amara Gonzalez Noya, Carlos Hernández Ceron, Isabel Izuzquiza Avanzini, Ana Latorre Diez, Pablo López Mato, Ana María Lorenzo Vizcaya, Daniel Peña Benítez, Milagros María Peña Zemsch, Lucía Pérez Expósito, Marta Pose Bar, Lara Rey González, Laura Rodrigo Lara.

La Fe UH Valencia

Dafne Cabañero, María Calabuig Ballester, Pascual Císcar Fernández, Ricardo Gil Sánchez, Marta Jiménez Escrig, Cristina Marín Amela, Laura Parra Gómez, Carlos Puig Navarro, José Antonio Todolí Parra.

Mataró H. Barcelona

Raquel Aranega González, Ramon Boixeda, Javier Fernández, Carlos Lopera Mármol, Marta Parra Navarro, Ainhoa Rex Guzmán, Aleix Serrallonga Fustier.

Sagunto H. (Valencia)

Enrique Rodilla Sala, Jose María Pascual Izuel, Zineb Karroud Zamrani.

Alto Guadalquivir H. Andujar (Jaen)

Begoña Cortés Rodríguez.

Ferrol UH (A Coruña)

Hortensia Alvarez Diaz, Tamara Dalama Lopez, Estefania Martul Pego, Carmen Mella Pérez, Ana Pazos Ferro, Sabela Sánchez Trigo, Dolores Suarez Sambade, Maria Trigas Ferrin, Maria del Carmen Vázquez Friol, Laura Vilariño Maneiro,

Infanta Margarita H. Cabra (Córdoba)

María Esther Guisado Espartero, Lorena Montero Rivas, Maria de la Sierra Navas Alcántara, Raimundo Tirado-Miranda.

Monforte de Lemos Public H. (Lugo)

José López Castro, Manuel Lorenzo López Reboiro, Cristina Sardiña González.

Virgen del Rocío UH Seville

Reyes Aparicio Santos, Máximo Bernabeu-Wittel, Santiago Rodríguez Suárez, María Nieto, Luis Giménez Miranda, Rosa María Gámez Mancera, Fátima Espinosa Torre, Carlos Hernandez Quiles, Concepción Conde Guzmán, Juan Delgado de la Cuesta, Jara Eloisa Ternero Vega, María del Carmen López Ríos, Pablo Díaz Jiménez, Bosco Baron Franco, Carlos Jiménez de Juan, Sonia Gutiérrez Rivero, Julia Lanseros Tenllado, Verónica Alfaro Lara, Aurora González Estrada

Marina Baixa H. Villajoyosa (Alicante)

Javier Ena, José Enrique Gómez Segado

Salamanca UH

Gloria María Alonso Claudio, Víctor Barreales Rodríguez, Cristina Carbonell Muñoz, Adela Carpio Pérez, María Victoria Coral Orbes, Daniel Encinas Sánchez, Sandra Inés Revuelta, Miguel Marcos Martín, José Ignacio Martín González, José Ángel Martín Oterino, Leticia Moralejo Alonso, Sonia Peña Balbuena, María Luisa Pérez García, Ana Ramon Prados, Beatriz Rodríguez-Alonso, Ángela Romero Alegría, Maria Sanchez Ledesma, Rosa Juana Tejera Pérez.

Defense General H. Zaragoza

Anyuli Gracia Gutiérrez, Leticia Esther Royo Trallero.

Palamós H. (Girona)

Ana Alberich Conesa, Mari Cruz Almendros Rivas, Miquel Hortos Alsina, José Marchena Romero, Anabel Martin-Urda Diez-Canseco.

Blanes County H. (Girona)

Oriol Alonso Gisbert, Mercé Blázquez Llistosella, Pere Comas Casanova, Angels Garcia Flores, Anna Garcia Hinojo, Ana Inés Méndez Martínez, Maria del Carmen Nogales Nieves, Agnés Rivera Austrui, Alberto Zamora Cervantes.

Salnes H. Vilagarcía de Arousa (Pontevedra)

Vanesa Alende Castro, Ana María Baz Lomba, Ruth Brea Aparicio, Marta Fernández Morales, Jesús Manuel Fernández Villar, María Teresa López Monteagudo, Cristina Pérez García, Lorena Rodríguez Ferreira, Diana Sande Llovo, Maria Begoña Valle Feijoo.

HM Montepríncipe UH

José F. Varona Arche.