The term artificial intelligence (AI) refers to the simulation of human intelligence processes, such as learning, reasoning, visual perception, natural (spoken) language recognition, decision making and problem solving, by programming algorithms (or sets of instructions) in computer systems.1–7 AI is already being applied to many areas of our daily lives (and will undoubtedly be applied to many more in the near future), but health and healthcare is one of the areas that has attracted the most interest.8–10 Initially, AI tools focused on very specific or repetitive tasks, but more flexible alternatives are now being developed that can adapt to different environments, such as helping clinicians make clinical decisions about an individual patient or supporting patients directly at home.3–7,10–15

The JANUS Group is an initiative under the auspices of the Barcelona College of Doctors (COMB) (https://www.comb.cat/es/serveis/salut-metge/janus), promoted by a group of health professionals who suffer or have suffered from a serious illness and who want to contribute to improving the patient's experience of the health system, based on their own experience as patients with health training, i.e. based on the doctor-sick duality (JANUS was the Roman mythological god of the two faces). Recently, the JANUS group published a document reflecting on various possible improvements in the outpatient setting (communication, new forms of consultation, empowerment of the patient and structural improvements),16 considering the outpatient visit as a central element of healthcare, whether in primary or specialised care, for medical or surgical conditions, and in public or private settings.

In this article, the JANUS group extends these considerations to the field of AI, with the aim of identifying concrete actions in which AI could help the patient in the outpatient setting. These reflections are not intended to be an exhaustive review of the subject but only to reflect the experience of JANUS members as health-trained patients regarding the expectations (and risks) that AI can offer in the outpatient setting.

MethodThis qualitative research study used a methodology based on deliberative dialogue in focus group (FG) meetings. The participants were members of the JANUS group, most of them with no prior knowledge of AI, who contributed their views based on their individual values and lived experiences as health-care providers and patients on the following initial question: How useful do you think AI could be in improving patient care in the outpatient setting? Two FG meetings were held in the last quarter of 2023. Sixteen JANUS members (Appendix A) participated in either of these two meetings (80% in both), together with two moderators and two computer engineers with expertise in AI to clarify any doubts that might arise during the discussion. Sixty percent were male and all had higher education.

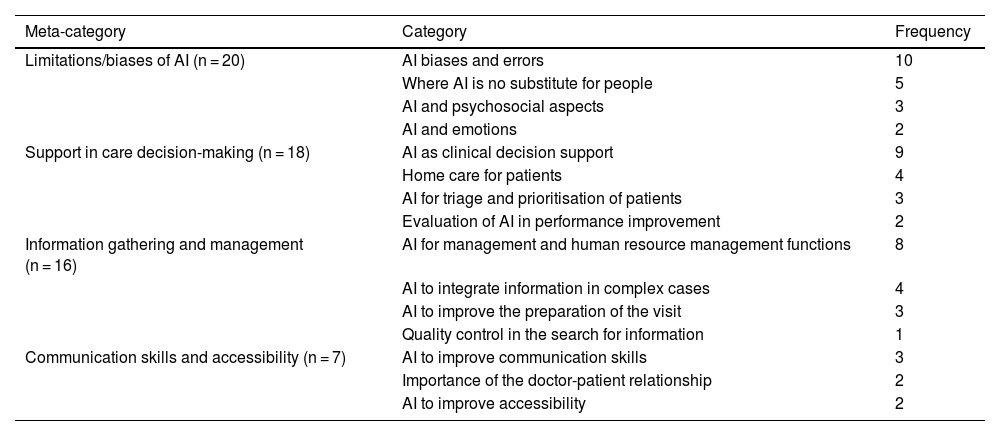

Data collection and analysis was carried out using MAXQDA software, which grouped the different concepts that emerged from the discussion into ‘categories’ (different ways of expressing the same concept) and ‘meta-categories’ (groupings of categories), allowing the identification of broad areas of interest (Table 1).17 The ‘frequency’ in Table 1 refers to the number of times the same category occurs. The dialogue was recorded and transcribed verbatim, and the mediators took additional notes and conducted a detailed analysis of the transcripts, field notes, interpretive notes and participants’ activities. It is important to note that the discussion focused on our public health system (CatSalut), which is different in other countries and settings.

MAXQDA analysis of the concepts (n), categories and meta-categories identified in the focus groups. Frequency refers to the number of times the same unit of meaning (category) is discussed.

| Meta-category | Category | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Limitations/biases of AI (n = 20) | AI biases and errors | 10 |

| Where AI is no substitute for people | 5 | |

| AI and psychosocial aspects | 3 | |

| AI and emotions | 2 | |

| Support in care decision-making (n = 18) | AI as clinical decision support | 9 |

| Home care for patients | 4 | |

| AI for triage and prioritisation of patients | 3 | |

| Evaluation of AI in performance improvement | 2 | |

| Information gathering and management (n = 16) | AI for management and human resource management functions | 8 |

| AI to integrate information in complex cases | 4 | |

| AI to improve the preparation of the visit | 3 | |

| Quality control in the search for information | 1 | |

| Communication skills and accessibility (n = 7) | AI to improve communication skills | 3 |

| Importance of the doctor-patient relationship | 2 | |

| AI to improve accessibility | 2 |

AI: artificial intelligence.

To provide some external reference, the reflections of these FGs were contrasted with: (1) those offered by the AI itself, in this case ChatGPT 3.5, one of the most widely used AI chatbots in use today. A chatbot is a computer programme that simulates human conversation with an end user; and (2) the recent proposal of 5 major objectives for improving patient safety and the quality of care provided (“The Quintuple Aim for Health Care Improvement” [QAHCI]), endorsed by the National Committee for Quality Assurance and the Joint Commission in the USA.18 These 5 objectives are: improving patients' health, improving patients' experience of care, reducing costs, addressing the working conditions of health professionals, and promoting health equity.

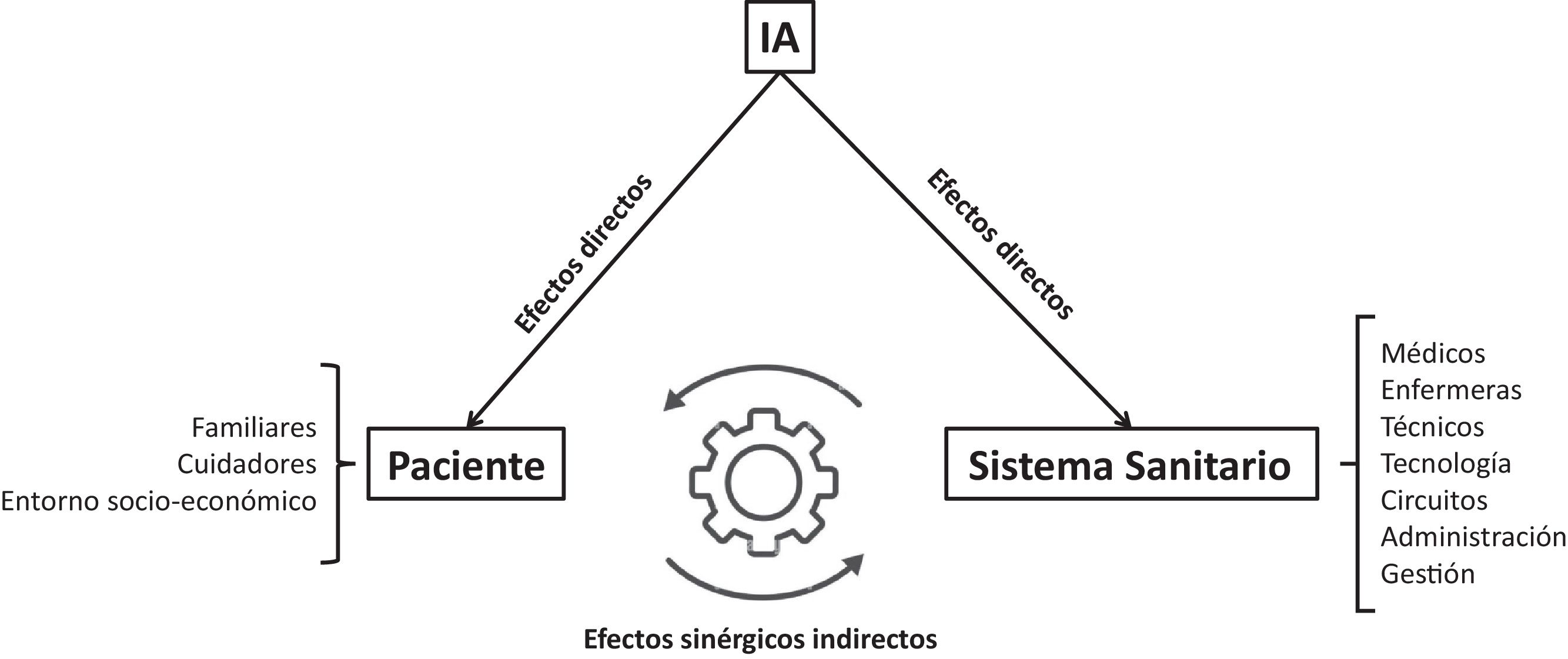

ResultsGeneral considerationsDirect, indirect and synergistic effects of artificial intelligenceAI could improve the patient experience in the outpatient setting through 3 different but complementary vectors (Fig. 1): (1) direct effects on the patient himself (and/or his family or social environment [e.g. caregivers]) which are listed in Table 2 and discussed in the following section (Specific proposals); (2) indirect effects, through the improvements that AI can induce in the healthcare system (professionals, technology, workflows, etc.). For example, better access to and functioning of the healthcare system, including relevant health information that patients can export from their personal domain to their own electronic health record (EHR). AI could also free the healthcare professional from administrative tasks, thereby “gaining time” for the human doctor-patient relationship, which would also improve the patient experience; and (3) synergistic effects, whereby the improvement of the patient experience thanks to certain AI actions could be passed on to the healthcare system itself, making it more efficient and/or safer.

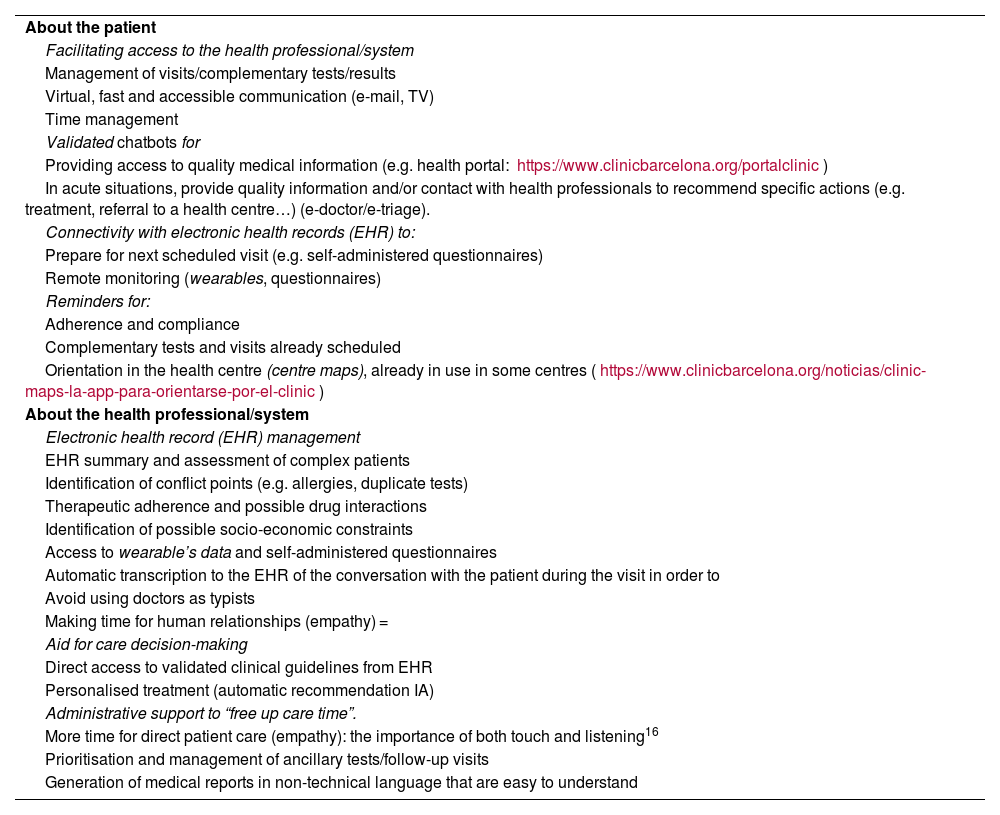

JANUS proposals on how artificial intelligence (AI) could improve the patient experience in the outpatient setting through its direct (on the patient) and indirect (on the healthcare professional/system [Fig. 1]) effects.

| About the patient |

| Facilitating access to the health professional/system |

| Management of visits/complementary tests/results |

| Virtual, fast and accessible communication (e-mail, TV) |

| Time management |

| Validated chatbots for |

| Providing access to quality medical information (e.g. health portal: https://www.clinicbarcelona.org/portalclinic) |

| In acute situations, provide quality information and/or contact with health professionals to recommend specific actions (e.g. treatment, referral to a health centre…) (e-doctor/e-triage). |

| Connectivity with electronic health records (EHR) to: |

| Prepare for next scheduled visit (e.g. self-administered questionnaires) |

| Remote monitoring (wearables, questionnaires) |

| Reminders for: |

| Adherence and compliance |

| Complementary tests and visits already scheduled |

| Orientation in the health centre (centre maps), already in use in some centres (https://www.clinicbarcelona.org/noticias/clinic-maps-la-app-para-orientarse-por-el-clinic) |

| About the health professional/system |

| Electronic health record (EHR) management |

| EHR summary and assessment of complex patients |

| Identification of conflict points (e.g. allergies, duplicate tests) |

| Therapeutic adherence and possible drug interactions |

| Identification of possible socio-economic constraints |

| Access to wearable’s data and self-administered questionnaires |

| Automatic transcription to the EHR of the conversation with the patient during the visit in order to |

| Avoid using doctors as typists |

| Making time for human relationships (empathy) = |

| Aid for care decision-making |

| Direct access to validated clinical guidelines from EHR |

| Personalised treatment (automatic recommendation IA) |

| Administrative support to “free up care time”. |

| More time for direct patient care (empathy): the importance of both touch and listening16 |

| Prioritisation and management of ancillary tests/follow-up visits |

| Generation of medical reports in non-technical language that are easy to understand |

This debate concerns both patients and professionals. In relation to patients, it is important to consider their psychological aspects so that their trust in the healthcare system is not diminished when it is linked to an AI, so it is important to consider the emotionality, empathy and emotional management of any AI system in an outpatient setting. With regard to professionals, the possible reluctance of older professionals to adopt AI tools is under discussion, due to their more classical and humanistic and less technological training, while the new generations (both professionals and patients) express greater confidence in AI In any case, it is believed that technology in general (including AI) should complement, but never replace, the clinician.11

Immediacy of response vs. quality of data and recommendationsThe quality of the data used by AI is a key aspect for its correct and safe functioning.1 If this is not the case, AI may suggest an incorrect diagnosis or actions different from those recommended by clinical guidelines, which could be inappropriate for the patient and even lead to possible criminal consequences for the professionals or the healthcare system itself. In this sense, the use by patients or professionals of AI tools of unproven quality may not provide the necessary quality of care under the guise of false accessibility to the health system. Initiatives on the quality of the information provided, such as the so-called “labelled AI” (https://keymakr.com/blog/data-labeling-in-healthcare-applications-and-impact) should therefore be considered.

Artificial intelligence as the third pillar of the healthcare system: towards personalised, predictive, preventive and participatory medicine (P4)The current healthcare system is based on two main pillars: primary care and specialised care. AI can facilitate the incorporation of a third pillar: the patient himself, both as a generator of relevant health information through “wearables” and refers to items such as watches, bracelets, headphones, glasses, shoes, key rings or other accessories that we “wear” that are capable of measuring and transmitting potentially relevant clinical information (such as physical activity, heart rate, body temperature or oxyhaemoglobin saturation, among others), or chatbots (perhaps from their own home). This may facilitate the transition from traditional medicine (reactive to a clinical situation that has already occurred) to personalised, predictive, preventive and participatory action (P4 medicine).19

Ethical principlesEthical principles are inescapable and should guide AI in healthcare by enhancing patient autonomy; promoting human rights, safety and the public interest; ensuring transparency and clarity, accountability and responsibility; and guaranteeing inclusivity and equity to promote a type of AI that is sustainable and responsible.11,20

Specific proposalsTable 2 shows a number of specific proposals. In relation to the possible direct effects of AI on the patient, the following stand out: (1) facilitating and prioritising their access to the specialised professional/health system/chatbot, in person or virtually (telemedicine21), depending on the results of the complementary tests requested, perhaps by generating a message (SMS, e-mail) automatically through AI; (2) optimising the patient's time management in their scheduled or urgent outpatient visits22–25; (3) connectivity with the patient's EHR to facilitate remote monitoring (biological variables, compliance) or to prepare for the next scheduled visit (e.g. self-administered questionnaires); and (4) orientation and guidance in the health centre (centre maps), already used in some hospitals.

In relation to the effects on the professional/healthcare system (thus with potential to indirectly affect the patient), the following stand out: (1) AI helps to improve EHR management, including the summary and assessment of complex patients, identification of conflict points (e.g. allergies, duplicate tests), therapeutic adherence and possible drug interactions, identification of possible socio-economic constraints, access to information from wearables and self-administered questionnaires; (2) automatic transcription into the EHR of the conversation with the patient during the visit, taking into account ethical and confidentiality issues, to avoid using doctors as typists and to free up time for human relationship (empathy); (3) Support healthcare decision making through direct access to validated clinical guidelines from the EHR and the resulting therapeutic recommendations presented by the AI; and (4) administrative support that “frees up care time” for direct patient care (empathy), e.g. by prioritising and managing complementary tests, scheduling consecutive visits, and/or producing medical reports in non-technical language that can be understood by patients without health care training.

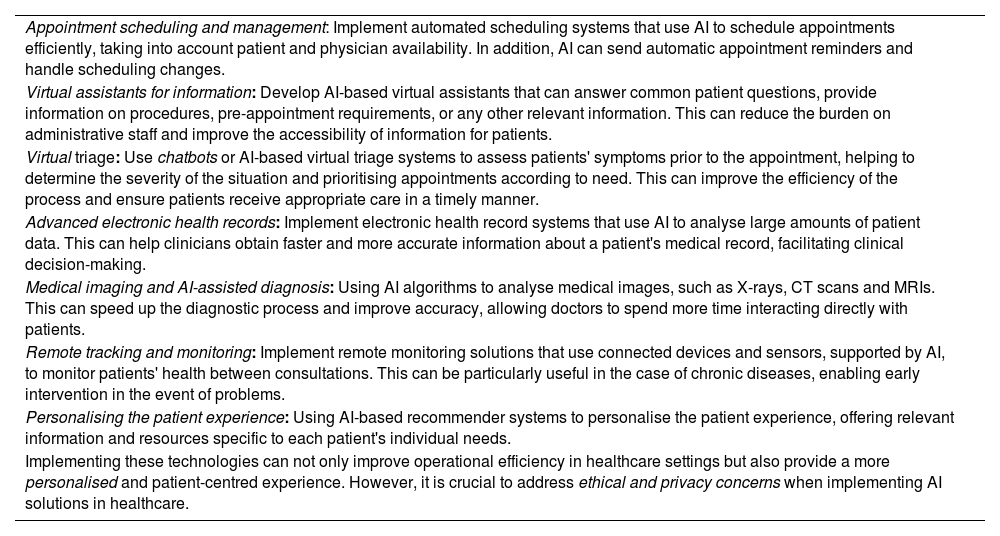

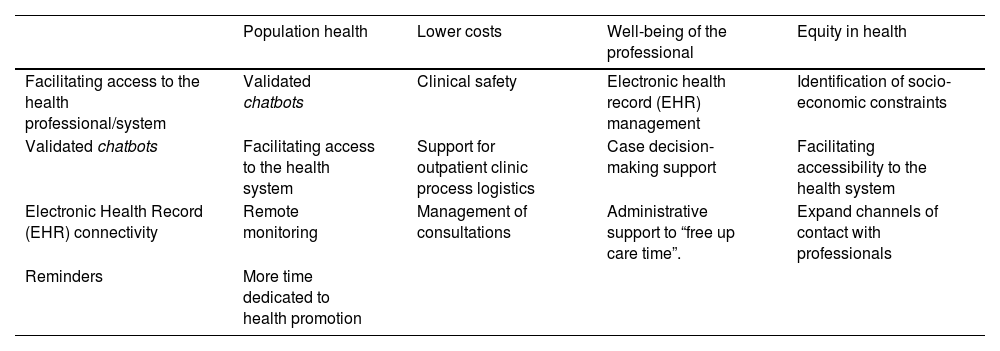

External substantiationTable 3 shows the answer given by ChatGPT 3.5 to the question “How can artificial intelligence be used to improve the patient experience in the outpatient clinic?”. It is worth noting the similarity of its answers to the results shown in Table 2. Finally, Table 4 shows that the JANUS proposals are well aligned with those proposed by the fivefold objective for assessing quality and health safety.18

ChatGPT proposals (December 2023) for improving the patient experience in the outpatient setting through artificial intelligence (AI).

| Appointment scheduling and management: Implement automated scheduling systems that use AI to schedule appointments efficiently, taking into account patient and physician availability. In addition, AI can send automatic appointment reminders and handle scheduling changes. |

| Virtual assistants for information: Develop AI-based virtual assistants that can answer common patient questions, provide information on procedures, pre-appointment requirements, or any other relevant information. This can reduce the burden on administrative staff and improve the accessibility of information for patients. |

| Virtual triage: Use chatbots or AI-based virtual triage systems to assess patients' symptoms prior to the appointment, helping to determine the severity of the situation and prioritising appointments according to need. This can improve the efficiency of the process and ensure patients receive appropriate care in a timely manner. |

| Advanced electronic health records: Implement electronic health record systems that use AI to analyse large amounts of patient data. This can help clinicians obtain faster and more accurate information about a patient's medical record, facilitating clinical decision-making. |

| Medical imaging and AI-assisted diagnosis: Using AI algorithms to analyse medical images, such as X-rays, CT scans and MRIs. This can speed up the diagnostic process and improve accuracy, allowing doctors to spend more time interacting directly with patients. |

| Remote tracking and monitoring: Implement remote monitoring solutions that use connected devices and sensors, supported by AI, to monitor patients' health between consultations. This can be particularly useful in the case of chronic diseases, enabling early intervention in the event of problems. |

| Personalising the patient experience: Using AI-based recommender systems to personalise the patient experience, offering relevant information and resources specific to each patient's individual needs. |

| Implementing these technologies can not only improve operational efficiency in healthcare settings but also provide a more personalised and patient-centred experience. However, it is crucial to address ethical and privacy concerns when implementing AI solutions in healthcare. |

Distribution of JANUS proposals on the potential impact of artificial intelligence on the outpatient experience in relation to the main 5 objectives for improving patient safety and quality of care (The Quintuple Aim for Health Care Improvement).18

| Population health | Lower costs | Well-being of the professional | Equity in health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitating access to the health professional/system | Validated chatbots | Clinical safety | Electronic health record (EHR) management | Identification of socio-economic constraints |

| Validated chatbots | Facilitating access to the health system | Support for outpatient clinic process logistics | Case decision-making support | Facilitating accessibility to the health system |

| Electronic Health Record (EHR) connectivity | Remote monitoring | Management of consultations | Administrative support to “free up care time”. | Expand channels of contact with professionals |

| Reminders | More time dedicated to health promotion |

These results show that: (1) AI offers several opportunities to improve patient experience in the outpatient setting (Table 2); (2) there is the potential for positive, bidirectional and complementary feedback between patient experience and healthcare system functioning (Fig. 1); and (3) AI applied to healthcare has the potential to redesign the healthcare system in a very significant way, by placing the patient truly at its centre through P4 medicine. Taken together, this information can be useful for planning and eventually improving healthcare in the outpatient setting.

Previous studiesNumerous previous studies have explored the potential (and limitations) of AI in healthcare.11,26 Publications on AI applications in the outpatient setting are less common and are mainly focused on primary care.3–5,12 None of them, however, combine the dual health professional-patient perspective provided by the JANUS group16 in this work, nor do they focus directly on the potential benefits (and limitations) of AI for patients.

JANUS proposalsGeneral recommendationsA number of potentially direct beneficial effects on both the patient and the health system were identified, but the possibility of synergies between the two was also highlighted (Fig. 1). In our view, this is an important aspect that has not been specifically highlighted in previous studies.

The importance of the potential lack of empathy that a patient may experience when being answered by a chatbot, rather than a human healthcare professional, has been discussed. However, it is interesting to note that a very recent study conducted in San Diego (California, USA) compared the quality and empathy of the answers provided by medical professionals to 195 questions posed by patients versus those provided by a well-known chatbot (ChatGPT), showing that the latter had a higher degree of quality and empathy than those provided by doctors.27 In any case, phrasing prompts appropriately is key to getting the right answer and avoiding what has become known as AI “hallucinations”.28

It was noted that the patient's positive perception of the immediacy of the AI's response can in no way override the essential quality of the data and recommendations. In this sense, the AI responses could recommend consulting existing “health websites” where the information can be complemented with verified medical quality content.

Specific recommendationsMany of the specific recommendations that have emerged from this analysis (Table 2) are similar to those published by previous studies3–7,12–14 which, in a way, validates them. However, their practical feasibility depends on the particular healthcare system in which they are intended to be implemented.

Another relevant aspect identified in this study is that AI can enable the availability of socio-health information on each patient to better personalise their clinical care, or enable the participation of healthy individuals (future patients) and current patients in the management of their own health, as they can collect, record and track health indicators through wearables or self-administered questionnaires, providing a rich source of information that empowers, enables and engages the patient in shared decision making. In this sense, it is considered that AI should evolve from its current, relatively “narrow” applications in healthcare (performing specific tasks repeatedly at the back of the medical consultation) to a broader and more flexible perspective that allows the current healthcare system (based on primary and specialised care) to be transformed into one that also includes the patient as a key player in the implementation of P4 medicine.19

Strengths and limitationsThe main strengths of this study are that: (1) it has focused on the patient's perspective and not on the healthcare system, as most previous studies had done; (2) the FGs have involved people in their dual capacity with healthcare training, contributing their dual previous experience as professionals and patients (JANUS group)16; and (3) it has focused on the outpatient setting, which may make some of its recommendations easier to implement. On the other hand, potential limitations include the relatively small size of the FGs and their geographical scope (limited to Barcelona), which may make it necessary to validate these proposals in other settings.

ConclusionsThe JANUS Group believes that AI offers numerous direct, indirect and synergistic opportunities to improve the patient experience in the outpatient setting, but at the same time its potential limitations and risks need to be carefully considered. It argues that AI can contribute to the redesign of the healthcare system, currently based on two pillars (primary and specialised care), by incorporating a third fundamental element: the patient (or the future patient) at the centre of the system, at home or through the export of their own clinical and biological data.

Ethical considerationsAll ethical requirements have been met.

FundingNone.

The authors would like to thank the Colegio Oficial de Médicos de Barcelona, and in particular Ms Nuria García Sánchez, for providing logistical support for the group's meetings. Due to editorial constraints, the members of the JANUS group who participated in the working meetings are listed in the Appendix A.

Discussion participants (in alphabetical order) in addition to the authors of this article:

- •

Aristoy, Elena

- •

Arteche, Natalia (and daughter)

- •

Aussó, Susana

- •

Babi, Pilar

- •

Bigorra, Joan

- •

Bruguera, Miquel

- •

Coca, Antonio

- •

De Peray, Josep Lluis

- •

Dominguez, Didier

- •

Escarrabill, Joan

- •

Fernández, Josi Luis

- •

García-Esparcia, Paula

- •

Hervás, Carles

- •

Mora, Yolanda

- •

Pallisa, Esther

- •

Querol, Dolors

- •

Sarroca, Miriam

- •

Tolchinsky, Gustavo

- •

Vilalta, Jordi

The names of the members of the JANUS group who participated in the working sessions are listed in the Appendix A.