Living donor kidney transplantation increases recipient and graft survival compared with cadaveric donor transplantation. Correct donor selection is essential to optimize transplant outcomes as well as post-donation safety. The aim of this study is to analyze the influence of baseline characteristics of living kidney donors on renal function, morbidity and mortality after nephrectomy.

Patients and methodsAn observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study was designed that included living kidney donors followed up at the Salamanca University Hospital between 2011 and January 2023. Statistical significance was considered if P≤.05.

ResultsNinety-one donors were included, 63% women, with a mean age of 52±10.8 years. 52.1% were overweight or obese, 9.9% had hypertension and 22% were dyslipidemic. Mortality was 0% and 84.3% had no complications. GFR (CKD-EPI) dropped from 92 to 57.1ml/min/1.73m2 at 1 month after nephrectomy. There was a significant increase in proteinuria at 1 month and 2 years. After nephrectomy, BMI, MAP, HbA1c, uric acid, total cholesterol, LDL and triglycerides increased (P≤.05).

ConclusionsThe mean GFR of donors as well as its compensation after nephrectomy was lower and slower than the figures reported in the literature, probably due to the higher mean age of our donors. The increased prevalence of obesity, dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia postdonation and worsening of HbA1c and MAP levels make strict monitoring of donors necessary. In our experience, kidney donation is a safe process with low morbidity and mortality.

El trasplante renal de donante vivo aumenta la supervivencia del receptor y del injerto frente al trasplante de donante cadáver. Es fundamental una correcta selección del donante para optimizar los resultados del trasplante, así como su seguridad post-donación. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar la influencia de las características basales de los donantes renales de vivo sobre la función renal, morbilidad y mortalidad tras la nefrectomía.

Pacientes y métodosSe diseñó un estudio observacional, descriptivo, trasversal en el que se incluyeron los donantes renales de vivo seguidos en el Hospital Universitario de Salamanca entre 2011 y enero del 2023. Se consideró significación estadística si P≤.05.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 91 donantes, 63% mujeres, con edad media de 52±10.8 años. El 52.1% tenían sobrepeso u obesidad, el 9.9% eran HTA y el 22% dislipémicos. La mortalidad fue 0% y el 84.3% no presentaron ninguna complicación. La TFG (CKD-EPI) cayó desde 92 hasta 57.1ml/min/1.73m2 al mes de la nefrectomía. Se produjo un incremento significativo en la proteinuria al primer mes, y al 2º año. Tras la nefrectomía aumentó el IMC, PAM, HbA1c, ácido úrico, colesterol total, LDL y triglicéridos (P≤.05).

ConclusionesLa media de FG de los donantes así como su compensación tras la nefrectomía fue inferior y más lenta a las cifras reflejadas en la literatura, probablemente por la edad media superior de nuestros donantes. El aumento de la prevalencia de obesidad, dislipemia e hiperuricemia posdonación y empeoramiento en las cifras de HbA1c y PAM hace necesario un control estricto de los donantes. En nuestra experiencia, la donación renal es un proceso seguro con escasa morbimortalidad.

The current prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Spain is 10%–15%, and the last decade has seen an increase in advanced chronic kidney disease (ACKD), with up to 30% of patients requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT). According to data from the National Transplant Organisation (NTO)/Sociedad Española de Nefrología registry, the number of people on RRT - haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis or transplantation - already reached 1363 per million population in 2020.1

Renal transplantation (RT) is the best treatment option for ACKD, as these patients have improved survival, quality of life, cost-effectiveness and fewer complications compared to dialysis.1 In haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, there is a chronic inflammatory state, oxidative stress and greater endothelial damage, which favours cardiovascular disease (CVD), leading to annual mortality rates of 15%–16% in Spain. Likewise, the survival of transplant patients is inversely proportional to the time spent on pre-transplant dialysis.2 For this reason, prophylactic transplantation (5%) is currently recommended, with recipients with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of less than 20ml/min/1.73m2.1,3

Improvements in health prevention and road safety have reduced the number of strokes and head injuries, thereby reducing the number of brain deaths. Advances in the care of critically ill patients have allowed the inclusion of donors in controlled asystole.4 Cadaveric donors are therefore increasingly older, with issues that force clinicians to make decisions about organ viability. These non-heart beating donors are not the “ideal donors” for transplantation in younger recipients or first transplants, who would benefit from living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT).3,5,6

LDKT is associated with longer survival than cadaveric kidney transplantation because of6–12: 1) the possibility of earlier transplantation; 2) a shorter delay in graft function; 3) a shorter cold ischaemia time; 4) greater HLA compatibility if there is a relationship between donor and recipient; 5) a lower acute rejection rate; and 6) the absence of haemodynamic instability usually associated with cadaveric donation.

Donor nephrectomy involves the loss of 50% of the renal mass, resulting in compensatory hypertrophy of the contralateral kidney with the sole aim of maintaining basal function by hyperfiltration, reaching 70% 12 months after nephrectomy.3,13–18 Follow-up shows that stabilisation or even positive compensation can last for years, but this process is limited by certain factors: age, male sex, obesity or kinship with the recipient. Donors aged 18–30 years recover GFR earlier and to a greater extent than other groups.18 According to the NTO, the mean glomerular filtration rate (GFR) would be 65.4ml/min 3 months after donation, and 71.7ml/min 8 years later.18–21 The likelihood of developing CKD after donation is directly related to the presence of several factors: genetic, immunological, smoking history, obesity, hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus (DM), black race and age.3,18,22,23 Recent studies report an incidence of 0.04%–0.7% of progression of CKD to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in donors, the risk of which is not linear but appears to increase from 10 years after donation, with albuminuria, HTN, cardiovascular or infectious episodes being favourable factors.3,15,22

The presence of proteinuria and albuminuria correlates with hyperfiltration. A 10%–12% increase in proteinuria has been reported in donors compared to controls, with a mean of 147mg/day at an average of 7 years post-nephrectomy.19,20 In addition, albuminuria is associated with progression to ESRD and increases the risk of HTN.3

Blood pressure (BP) increases in donors at a higher rate than in the rest of the population: an average elevation of 6mmHg in systolic pressure and 4mmHg in diastolic pressure, showing an increased risk of short and long term HTN.3 The NTO reports an increase in the incidence of HTN, which is 2.3% at 3 months post-nephrectomy and 10.9% 6 years later. Furthermore, its occurrence is associated with proteinuria, decreased GFR, CVD and death.20–22 Hypertensive pre-nephrectomy patients have an increase in BP in the first 2 months post-nephrectomy, with no significant change in the following 5 years.

After nephrectomy, donors should be periodically evaluated to detect changes in CVRF and renal changes and to take preventive measures. In Spain, there is a loss to follow-up of 18% and 13% at 4 and 6 years,3 respectively.

Renal donors have a higher risk of long-term HTN than a similarly healthy non-nephrectomised population,24 renal19,23 and cardiovascular disease, but there is no evidence of an increased risk of all-cause mortality or long-term cardiovascular events. Further studies with longer follow-up and larger sample sizes are needed to analyse the impact of donation. This is the aim of our study.

Patients and methodsAn observational, descriptive, cross-sectional, descriptive study was carried out at the University Hospital of Salamanca between January 2011 and December 2022, with follow-up until January 2023, to determine the baseline characteristics of donors, short- and long-term morbidity and mortality, to analyse changes in the main CVRFs after nephrectomy and determine the influence of nephrectomy on renal function and proteinuria.

Inclusion criteria were: over 18 years of age and meeting the donor selection criteria of the clinical guidelines for kidney transplantation. Patients with no follow-up at our centre after 3 months post-nephrectomy were excluded.

Baseline characteristics and donor history were analysed: age, sex, history of lithiasis, smoking habit and evolution of different clinical variables: body mass index (BMI), HT on treatment, systolic BP, diastolic BP, mean BP, dyslipidaemia on treatment and analytical variables: GFR by CKD-EPI, creatinine clearance (CrCl), baseline creatinine, carbohydrate intolerance (baseline glucose and glycosylated haemoglobin [HbA(1c)]), 24h proteinuria, 24h albuminuria, triglyceride, total cholesterol, LDL, HDL and uric acid levels at 1, 2, 5, 7 and 10 years after nephrectomy. Donor follow-up was conducted at the RT clinic of the Nephrology Department of the University Hospital of Salamanca at one month, three months and annually. Laboratory tests were performed at the Biochemistry Department of the hospital.

IBM® SPSS® Statistics v. 26 was used for statistical analysis. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate whether the variables followed a normal distribution, in which case they were presented by the mean±standard deviation, and by the median (interquartile range) for those that did not. Student's t-test, Wilcoxon and Mann-Whitney U-tests were used to analyse the variables for quantitative variables and chi-squared for qualitative variables. Statistical significance was considered when P<.05.

The study was evaluated and approved by the Ethics Committee for Research with Medicines of the Salamanca Health Area, with the code: PI2023 04 1260-TFG.

ResultsBaseline donor characteristics63% of living kidney donors were female, with a median age of 52±10.8 years.

The mean BMI was 25.7±3.6kg/m2. Pre-nephrectomy, 39.6% of donors were overweight and 12.5% had grade I obesity.

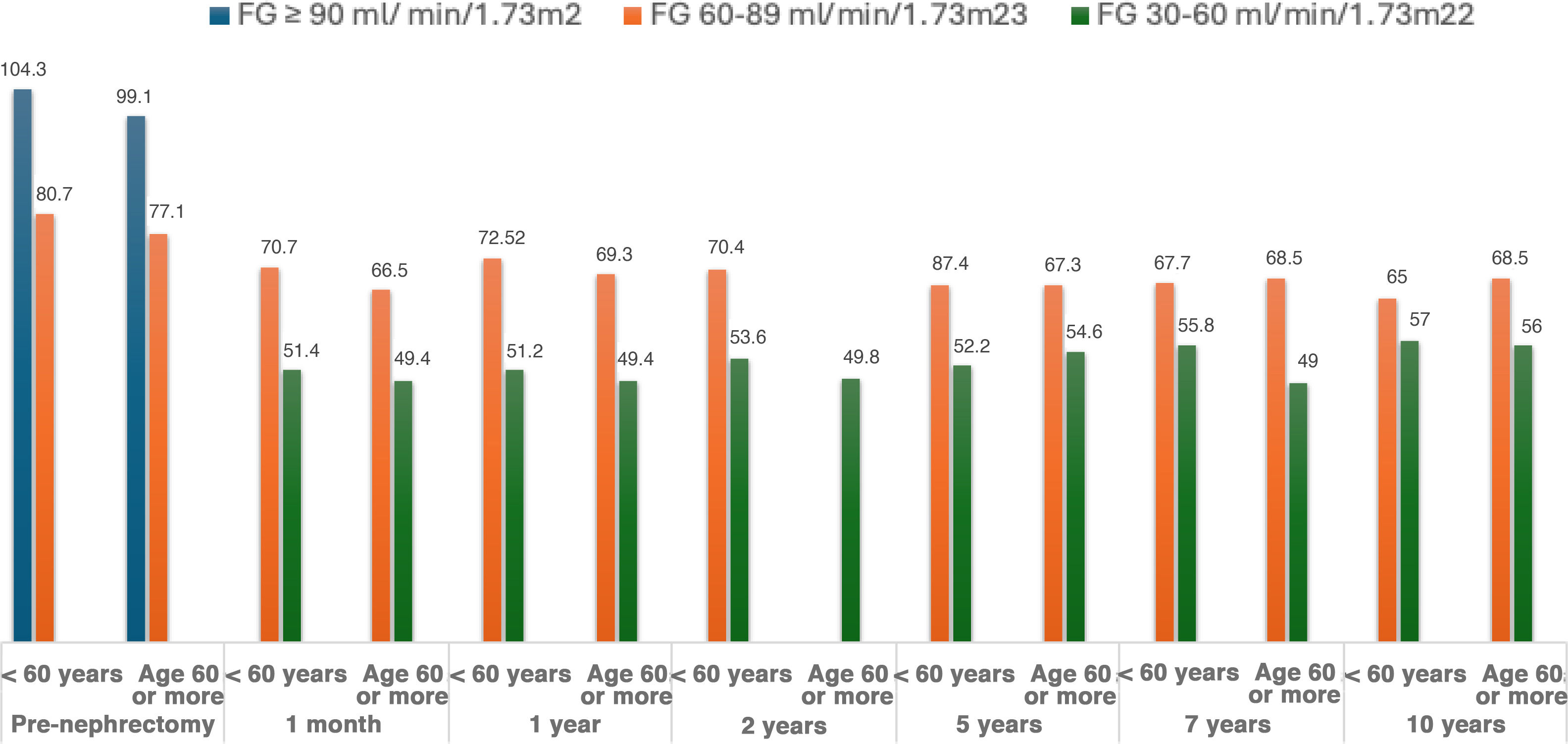

Median baseline creatinine was 0.8±0.2mg/dl, median GFR (CKD-EPI) was 92±14.6ml/min/1.73m2, and median CrCl was 114ml/min. When stratified by age group, higher GFR levels were observed in the young, which decreased according to the age group of the donors (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Median proteinuria was 112, and mean albuminuria was 8.00±7.60mg/day.

Medical history and substance abuse9.9% of renal donors had HTN, 7.7% with 1 drug and 2.2% with 2 drugs.

Only 2.2% had carbohydrate intolerance and the prevalence of dyslipidaemia was 22%.

3.4% of donors had hyperuricaemia and 13.2% had a history of lithiasis.

25.3% reported being active smokers at the time of kidney donation.

Donor follow-upMortality was 0% and 84.3% had no complications.

Changes in kidney function after nephrectomy in donorsMean creatinine levels decreased from the 1-month follow-up (1.2mg/dl) to the 10-year follow-up (1mg/dl). There were significant differences between the creatinine levels recorded before surgery and the different periods analysed up to year 7 (P<.05), with a significant decrease between the different periods analysed at follow-up.

A 38% decrease in GFR was observed in the first month of follow-up. This value increased progressively from 57.1ml/min/1.73m2 at the one-month follow-up, to 62ml/min/1.73m2 at the 10-year follow-up (Table 2).

Changes in GFR (CKD-EPI) during follow-up of living donors and percentage of GFR achieved with respect to baseline (>60ml/min/1.73m2 vs. ≤60ml/min/1.73m2).

| GFR (ml/min/1.73m2), average±SD (n) | Percentage compared to pre-nephrectomy | Interperiod significance | pre-nephrectomy P value | Percentage compared to pre-nephrectomy with GFR≥60ml/min/1.73m2 | Percentage compared to pre-nephrectomy with GFR<60ml/min/1.73m2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-nephrectomy | 92±14.6 (73) | 100 | 0 | |||

| 1 month | 57.1±11.6 (67) | 62.1 | 0 | 0 | 32.8 | 67,2 |

| 1 year | 59.5±13.1 (58) | 64.7 | 0 | 0 | 41.4 | 58,6 |

| 2 years | 60.2±11.4 (54) | 65.4 | 0 | 0 | 47.4 | 52,6 |

| 5 years | 62±8.9 (29) | 67.4 | 0.007 | .004 | 62.1 | 37,9 |

| 7 years | 61.8±8.1 (15) | 67.2 | 0.011 | .984 | 61.1 | 38,9 |

| 10 years | 62±6.06 (6) | 67.4 | 0.138 | 0 | 50 | 50 |

During follow-up, there was an increase in proteinuria, but this was only significant between the pre-nephrectomy period and the first month. Although it increased, when comparing the pre-nephrectomy values with the different periods, it only reached statistical significance up to the second year.

Changes in BP and BMI after nephrectomy in donorsRegarding the prevalence of living donors with HTN, less than 5% of living donors had HTN at follow-up in the first 2 years after donation, but this percentage increased to almost 18% at the 7-year follow-up. The incidence of HTN increased from 0% at the 1-year follow-up to 11.5% at the 5-year follow-up.

The mean BMI of living donors showed a progressive increase from 25.7kg/m2 before nephrectomy to 27.6kg/m2 at 10 years, with a prevalence of obesity of 33.3% at 10 years after kidney donation.

Changes in kidney function stratified by age, BMI, presence of HTN, smoking, dyslipidaemia, hyperuricaemia or history of pre-nephrectomy lithiasisSince GFR is affected by age, 2 groups were established: <60 vs. ≥60 years. Significant differences in GFR evolution were observed between these 2 age groups up to 2 years of follow-up with lower GFR in the ≥ 60 years, but donors aged≥60 years were observed to experience higher GFR recovery (from 51,2ml/min/1.73m2 at 1 month to 64.3ml/min/1.73m2 at 10 years) compared to those under 60 years, where GFR remained stable at 10 years compared to the first month (Table 3 and Fig. 2).

Changes in glomerular filtration rate (CKD-EPI) during the follow-up of living donors, by age ranges.

| GFR (ml/min/1,73m2)<60 years old, mean±SD (n) | Percentage compared to pre-nephrectomy | GFR (ml/min/1,73m2)≥60 years, mean±SD (n) | Percentage compared to pre-nephrectomy | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-nephrectomy | 93.4±14.7 (53) | 89.1±15.1 (24) | .076 | ||

| 1 month | 59.6±11.8 (47) | 63.8 | 51.2±8.8 (20) | 57.4 | .006 |

| 1 year | 61.9±13.1 (42) | 66.4 | 53.1±11.2 (16) | 59.6 | .022 |

| 2 years | 63.5±10.4 (41) | 67.9 | 49.8±7.4 (13) | 55.9 | 0 |

| 5 years | 62.9±9.3 (20) | 67.4 | 60.2±8 (9) | 67.6 | .47 |

| 7 years | 61.8±7.8 (12) | 66.1 | 62±11.3 (3) | 69.6 | .964 |

| 10 years | 59.7±4.6 (3) | 63.9 | 64.3±7.4 (3) | 72.2 | .405 |

No differences were found in GFR during follow-up between patients with BMI above and below 30kg/m2, between those with a history of HTN, history of dyslipidaemia, smoking, presence of hyperuricaemia or history of lithiasis versus patients without such a history (P>.05).

DiscussionCadaveric kidney donors are increasingly older, with greater vascular involvement and occasionally diabetic. In communities such as Castilla y León, their average age was 60.7 years in 2022, which limits the possibilities and prolongs the time in RRT of younger recipients.3 The average age of our living renal donors was between 31–59 years, which is a determining factor in making LDKT the best option for our youngest recipients.

The World Health Organisation lists obesity as a global pandemic, capable of reducing life expectancy by 5–20 years, and the cause of death of 2.8 million person-years. Obesity and overweight are related to the onset of type 2 DM, HTN, sleep apnoea, CKD, etc. In our study, up to 50% of donors were overweight or obese, a percentage that increased after nephrectomy. In parallel with the increase in BMI, we observed a worsening of the lipid profile and uric acid levels during follow-up. We need to ensure the long-term safety and survival of our donors by weighing the pros and cons in donors and recipients. If necessary, the donation process should be delayed until normal pre-nephrectomy weight is achieved, and post-nephrectomy lifestyle changes should be intensified to prevent the occurrence of CVRF, the development of CVD or CKD.4,14,19,21,22,23

The proportion of patients with carbohydrate intolerance was minimal due to prevention through screening,3 but we did find higher fasting glucose and HbA1c levels in patients≥60 years post-donation, which may be related to the loss of insulin reserve, or increased insulin resistance with age. In our study, age was also associated with a worsening lipid profile, which could be due to the sedentary lifestyle of older people and, in the case of women, the hormonal influence of the menopause.

The prevalence of HTN increased after nephrectomy. The following factors determined its occurrence: the worsening of the glycaemic profile, the increase in BMI, the fact that the patients became mono-renal and that they presented with CKD at some point after the donation. In addition, the prevalence of hypertension increased with age, as a consequence of the loss of elasticity of the arteries.

After nephrectomy, there was a decrease in GFR, which was gradually compensated by renal hyperfiltration. The same happened with CrCl, which decreased, with creatinine levels increasing after nephrectomy and then decreasing.

The NTO report18 shows an increase in the percentage of living kidney donors aged≥60 years, from 15% in 2010 to 25% as of 2018.18 In our case, 29% of the donors were≥60 years old, which may justify a lower GFR and CrCl immediately after nephrectomy, as a consequence of a lower and slower initial compensation, since although this starts from the first month, the improvement is evident in the long term, especially from the fifth year post-donation.

Questions have been raised in recent years as to whether criteria for defining CKD should be established by adjusting GFR for age, such that a GFR of less than 45ml/min/1.73m2 should be considered in patients older than 65 years and less than 75ml/min/1.73m2 in patients younger than 40 years. Although after nephrectomy the GFR decreased by about 30% compared to the pre-donation GFR, and although up to 30% of patients over 65 years of age had a GFR of less than 45ml/min/1.73m2 at some point in their progression, over time no patient over 65 years of age could be classified as having CKD, according to the decrease in GFR.

The presence of proteinuria≥500mg/day or albuminuria≥300mg/day is an absolute contraindication to donation; Although some patients in our study had proteinuria≥150mg/day at the time of pre-nephrectomy, this was not a contraindication to donation because they had albuminuria less than 30mg/day, which is considered a more sensitive marker of CKD than proteinuria.3

As a consequence of post-donation hyperfiltration, there was an increase in donor proteinuria at one month, probably overestimated by the existence of postoperative haematuria. Subsequently, there was only a significant increase compared to preoperative proteinuria in the second year, but it was less than 200mg/day and much lower than the results published by the NTO.18 Proteinuria was more prevalent in ≥60 years old and obese, circumstances in which there is already baseline glomerular hyperfiltration, which makes us reiterate that we must be stricter in the metabolic control of our donors both pre- and post-nephrectomy. However, we did not find more proteinuria in hypertensive patients, which we attribute to the low prevalence of hypertension, its strict control or the short follow-up period of the study.

Both decreased GFR and increased urine albumin/creatinine ratio are associated with increased adverse events: cardiovascular mortality, overall mortality, renal failure treated with RRT, acute renal failure and progression of CKD.19–22,23 The coexistence of both factors multiplies the risk. Contrary to what has been published, we have not demonstrated the influence of obesity, HTN, hyperuricaemia, smoking, history of lithiasis, dyslipidaemia or sex on the progression of GFR. We need to extend the follow-up period of our donors to confirm or not the impact of these CVRFs on GFR, proteinuria and, therefore, on future morbidity and mortality.

Conclusions- 1

After kidney donation, GFR decreased by approximately 30%, but renal hyperfiltration revealed that a very small percentage of our donors had CKD 3A.

- 2

In our study, the mean donor GFR achieved after nephrectomy was lower than reported because our donors were older with a previous lower mean GFR, which limited renal compensation, which was slower and persisted up to 10 years of follow-up.

- 3

Our study shows a worsening of CVRF (hypertension, obesity, lipid and glycaemic profile and uric acid) after donation, without affecting GFR. It is necessary to be stricter in their subsequent control to reduce the possible higher future morbidity and mortality of our donors, which could not be observed due to the short follow-up period.

- 1

Pilar Fraile Gómez: conception, design of the study, critical review of the article and final approval of the version submitted.

- 2

Nina Duarte Duarte: data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and drafting of the article.

- 3

Alejandro Martín Parada: conception, design of the study and critical review of the intellectual content.

- 4

Alexandra Lizarazo: data collection, analysis and interpretation.

- 5

Celia Rodriguez Tudero: data collection, analysis and interpretation.

- 6

Fernanda Lorenzo Gómez: critical review of the intellectual content and final approval of the version submitted.

This study has been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee for Research with Medicinal Products of the Salamanca Health Region, under code PI2023 04 1260-TFG, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients included in this original article gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

None.