This research answers the following question: How do the competencies and attitudes of university faculty toward artificial intelligence (AI) impact student learning? Using human capital theory and stakeholder theory, this research highlights the importance of university faculty. The research uses an adaptation of a digital competence framework specifically for AI competence. A total of 105 responses from professors in business studies (e.g., entrepreneurship, strategy, finance, and marketing) were collected from university faculty. Four hypotheses were proposed, two of which were confirmed. Professors' ability to leverage AI for feedback, assessment, and pedagogy is linked to their commitment to enhancing student learning. Professors' attitudes toward the use of AI, data governance, and ethical considerations are also associated with their focus on improving student learning. The study finds that faculty AI competence can enhance institutional effectiveness. Educators are a crucial resource for higher education institutions. Equipping them with the necessary skills for the effective use of AI can enhance both institutional capacity and pedagogical innovation.

Higher education institutions (HEIs) are navigating an era of profound transformation, driven by technological disruption, shifting demographics, and evolving global labor market demands (Gaebel & Zhang, 2024). Among these changes, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a key catalyst, reshaping core activities such as teaching, learning, and research (World Economic Forum, 2024). Integrating AI into HEIs has sparked great debate about its consequences, highlighting the need to understand how AI can be incorporated into educational processes (Hervás-Gómez et al., 2024). While some scholars remain optimistic (Escotet, 2023), many experts' voices emphasize the importance of achieving a strong balance between AI-mediated and human interaction in learning environments (Fengchun & Holmes, 2023), highlighting the relevance of educators' human agency function (Molina et al., 2024). Nevertheless, a critical dimension often overlooked in current debates is how university faculty perceive AI’s impact on student learning, especially considering their pivotal role in aligning educational strategies with societal and labor market transformations (George & Wooden, 2023). This study addresses the empirical gap by evaluating faculty AI competency, defined as the knowledge, skills, and values that educators must develop to use AI effectively and ethically in higher education settings (Fengchun & Cukurova, 2024; Laurillard, 2013).

The urgency of this research is underscored by international reports on the transformative economic impact of AI. The IMF emphasizes that advanced economies are facing rapid changes due to their reliance on cognitive-intensive roles, underscoring the importance of education and skill development (Cazzaniga et al., 2024). While concerns remain about inequality, evidence suggests that AI-driven productivity gains may foster income growth rather than displacement. Consistently, the Future of Jobs Report 2025 projects a net increase of 78 million jobs, with 92 million displaced and 170 million created, equal to 14 % of current global employment (World Economic Forum, 2025). McKinsey estimates that the transformation of higher education institutions (HEIs) could yield trillions in added value and result in $1.2 trillion in annual labor cost reductions, highlighting the importance of HEIs as primary suppliers of human capital (Chui et al., 2023). This requires institutional innovation, particularly through the development of educators’ AI competency as key stakeholders (Chandler, 2024).

However, there is limited empirical evidence regarding how faculty perceive the impact of AI on student learning and the factors that influence this critical process. This gap is particularly noticeable when considering the faculty’s role in aligning institutional strategies with the broader needs of society and labor market demands (George & Wooden, 2023). Educators' AI competency encompass the knowledge, skills, and values that teachers must master in the age of AI (Fengchun & Cukurova, 2024) at all levels, including universities, to effectively prepare the younger generation for employment and labor market demands. (Laurillard, 2013). This teaching gap is highlighted in the report "Shaping the Future of Learning: The Role of AI in Education" (World Economic Forum, 2024).

Based on seminal economic and management theories such as Human Capital and Stakeholder theory and leveraging digital competencyframeworks (Núñez-Canal et al., 2024), specifically the adaptation of the DigCompEdu tool to AI competency(Ng., 2023), this study evaluates faculty proficiency and student perception of learning.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows: Section 2 `Literature review' presents the literature review and development of hypotheses, Section 3 `Materials and methods' describes the research methodology and data collection procedures, Section 4 `Results' reports the results, Section 5 `Discussion' discusses the findings and outlines the study’s limitations, and Section 6 `Conclusions' concludes with implications and directions for future research.

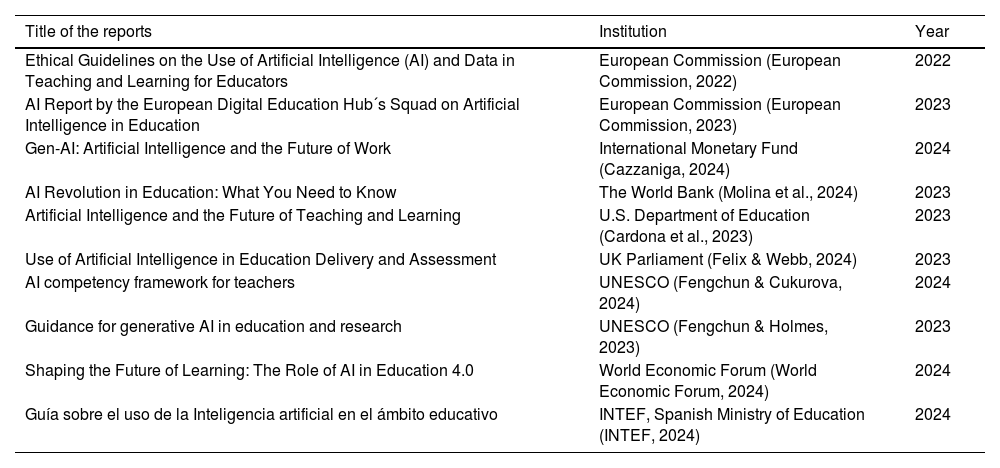

Literature reviewAI reshaping higher education contextAcademic interest in AI within higher education has grown rapidly, as reflected in numerous studies analyzing emerging trends and key themes (Guo et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024). A Google Scholar search for “Artificial Intelligence” and “Higher Education” in 2024 alone returns nearly 16,900 results, while >530 publications are indexed in the Web of Science between 2024 and 2025. This sharp increase, further substantiated by recent international institutional reports (see Table 1), underscores both the dynamism of the field and the growing challenge of synthesizing its current state of development.

Reports of AI in education.

| Title of the reports | Institution | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Ethical Guidelines on the Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Data in Teaching and Learning for Educators | European Commission (European Commission, 2022) | 2022 |

| AI Report by the European Digital Education Hub´s Squad on Artificial Intelligence in Education | European Commission (European Commission, 2023) | 2023 |

| Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work | International Monetary Fund (Cazzaniga, 2024) | 2024 |

| AI Revolution in Education: What You Need to Know | The World Bank (Molina et al., 2024) | 2023 |

| Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Teaching and Learning | U.S. Department of Education (Cardona et al., 2023) | 2023 |

| Use of Artificial Intelligence in Education Delivery and Assessment | UK Parliament (Felix & Webb, 2024) | 2023 |

| AI competency framework for teachers | UNESCO (Fengchun & Cukurova, 2024) | 2024 |

| Guidance for generative AI in education and research | UNESCO (Fengchun & Holmes, 2023) | 2023 |

| Shaping the Future of Learning: The Role of AI in Education 4.0 | World Economic Forum (World Economic Forum, 2024) | 2024 |

| Guía sobre el uso de la Inteligencia artificial en el ámbito educativo | INTEF, Spanish Ministry of Education (INTEF, 2024) | 2024 |

Source: Own elaboration.

Within this research context, distinct lines of inquiry are gaining prominence. A central focus of recent studies is the promotion of a human-centered approach to AI integration in higher education (Fengchun & Holmes, 2023; McCarthy et al., 2023; Molina et al., 2024), where educators are positioned as key agents in this transformation (Lee et al., 2024). One underexplored dimension involves faculty perceptions of the impact of generative AI on student learning (Santos Villalba et al., 2024). Faculty hold a pivotal role in guiding students toward informed and responsible AI use (Rahimi & Tafazoli, 2022). Their responsibility lies in integrating AI in ways that enrich learning, while simultaneously mitigating risks such as cognitive offloading, diminished critical thinking, and ethical concerns related to data privacy and algorithmic bias (Ciarra Tejada & Parra Sánchez, 2024).

International reports suggest that concerns over AI-induced job displacement may be exaggerated; instead, the rapid pace of adoption underscores an urgent need for widespread upskilling and reskilling (Cazzaniga et al., 2024; World Economic Forum, 2025). AI is transforming higher education in two principal ways (Gaebel & Zhang, 2024): first, by establishing education as a cornerstone for developing human capital suited to an AI-driven labor market (Brey & van der Marel, 2024; Jimeno & Lamo, 2024), and second, by reconfiguring internal academic processes, including pedagogical practices, assessment models, and institutional structures (Fengchun & Holmes, 2023; George & Wooden, 2023). Faculty are increasingly adopting AI tools for instructional design, feedback provision, and research activities (Molina et al., 2024). However, persistent concerns remain regarding academic integrity, ethical implementation, and the potential erosion of students’ cognitive engagement (Griesbeck et al., 2024; Gerlich, 2025). These challenges have prompted calls for institutional strategies centered on digital skills development, ethical integration, academic honesty, and faculty-driven innovation in instructional design (Msambwa et al., 2025).

Targeted investment in faculty training strengthens teaching competency, driving pedagogical innovation and organizational efficiency (Ren & Wu, 2025). Faculty acceptance and engagement are essential for legitimizing digital transformation (Shata & Hartley, 2025), while their role at both institutional and systemic levels reinforces the signaling capacity of universities and their broader social mission (Colther & Doussoulin, 2024; Tian & Zhang, 2025). This study addresses these challenges by examining faculty as key stakeholders in fulfilling the mission of higher education institutions. Enhancing educators’ AI competency and fostering positive attitudes toward adoption (Ehuletche et al., 2018; Núñez-Canal et al., 2022; Torrato et al., 2020) can reinforce institutional human capital, boost competitiveness, and support long-term sustainability (Brey & van der Marel, 2024).

By following this strategy, HEIs are better positioned to foster innovation, meet labor market demands, and increase their societal impact (World Economic Forum, 2024).

Educators’ attitudes and the improvement of digital competencyThe literature on technology in education consistently highlights that educators' attitudes serve as a crucial predictive factor for the successful implementation and use of technology in educational settings. (Ghomi & Redecker, 2019; Núñez-Canal et al., 2022; Rahimi & Tafazoli, 2022; Torrato et al., 2020).

In a similar vein, several scholars confirm the significant correlation between professors’ AI-related competencies and their attitudes toward technology, emphasizing its influence on students’ learning experiences and outcomes (Omar et al., 2024). Other authors (Abbasi et al., 2025) support and expand upon this relationship, linking it not only to curriculum development and the identification of students’ knowledge gaps, but also to the encouragement of educators to pursue enhanced professional development.

Moreover, several studies demonstrate that educators who possess the competency and dispositions necessary to integrate AI ethically and effectively can enhance teaching practices and tackle key challenges, such as fostering critical thinking, promoting fairness, and ensuring the responsible use of technology (Meirbekov et al., 2022). Therefore, faculty attitudes are pivotal in shaping the perception and implementation of AI within the academic community, directly influencing its potential to foster innovation and collaboration among stakeholders, including students, employers, and policymakers (Rahiman & Kodikal, 2024; Rahimi & Tafazoli, 2022). Empirical evidence also suggests that educators exhibit highly positive attitudes toward the integration of AI in both teaching and research, highlighting the relevance of targeted professional development initiatives (Omar et al., 2024; Villegas-José & Delgado-García, 2024).

AI competence frameworkThe DigComp framework for digital citizenship, developed by the European Commission (Ferrari et al., 2014), serves as a foundational instrument for assessing digital competency. Building on this initiative and acknowledging the central role of education in shaping a more technologically advanced society, the DigCompEdu model was introduced to strengthen educators’ digital capabilities (Redecker, 2017). This widely recognized European framework categorizes digital competence into six domains, encompassing 22 specific skills. It offers educators a structured approach to improving their proficiency in the use of digital technologies (Cabero-Almenara et al., 2022; Cabero-Almenara & Palacios-Rodríguez, 2020; De Obesso et al., 2023; Núñez-Canal et al., 2022).

The advancement of AI integration necessitates an update to existing digital competency frameworks in order to address emerging challenges. As a result, digital literacy has progressively evolved into AI literacy (Ng et al., 2021), now regarded as an essential skill for educators. AI literacy encompasses the ability to critically assess, collaborate with, and utilize AI technologies effectively across diverse personal and professional contexts (Long & Magerko, 2020). This study follows the work of Ng et al. (2023), who identified limitations in the original DigCompEdu framework and proposed a revised version, adapting its structure to reflect the specific challenges and opportunities presented by AI in educational contexts. This adaptation, grounded in a conceptualization of AI literacy derived from a systematic review (Ng et al., 2021), introduces four critical dimensions to Redecker’s original framework: knowledge and understanding, application and use, evaluation and creation, and ethical perspective. The AI-enhanced framework expands the six original DigCompEdu domains, providing a more adaptable tool that aligns with the demands of contemporary education. It recognizes the dynamic nature of digital technologies and underscores the importance of continuous professional development for faculty and academic leadership within HEIs. Other models of AI literacy are also worth noting due to their comprehensive treatment of the phenomenon, such as the framework proposed by Mills et al. (2024). In parallel, related concepts—such as algorithm literacy—have emerged in academic discussion, highlighting the need for increased awareness and education regarding AI use among both students and educators (De Obesso et al., 2024).

For this study, the revised model proposed by Ng (2023) was utilized, which, drawing on the literature on AI literacy, offers a reformulation of the six original domains, structured as follows:

Area 1. Professional engagement: This section emphasizes critical reflection on the foundations of AI and examines how its strengths and limitations may influence educational practices. It also highlights the potential of AI to foster collaboration and communication within institutions and between educators and learners. The area includes the following variables: 1–1. Participation in AI-enabled learning, 1–2. Perceived usefulness of AI tools, 1–3. Evaluation of AI impact, 1–4. Ethical and responsible use of AI and data, 1–5. Understanding AI systems and algorithmic functioning, 1–6. Interaction with and refinement of AI tools, 1–7. Generation of data for AI training, and 1–8. Alignment with EU ethical guidelines.

Area 2. Digital resources: This area encourages educators to adopt AI-based tools that enhance teaching and learning by enabling the creation of personalized and enriched learning materials, while also facilitating the efficient development and distribution of digital content. It includes the following variables: 2–1. Data security and privacy, 2–2. Compliance with data processing regulations, 2–3. Control over data access, 2–4. Identification of risks in personal data processing, 2–5. Transparency requirements in AI systems, 2–6. Strategies for integrating digital content, and 2–7. Data quality standards in AI applications.

Area 3. Teaching and learning: This area explores how the integration of AI into teaching practices can enhance lesson planning, enable rapid responses to student inquiries, improve collaborative learning strategies, and support flexible, personalized instructional approaches. It includes the following variables: 3–1. Application of AI in educational settings, 3–2. Implementation of educational innovation through AI, 3–3. Role of AI in the student learning experience, 3–4. Use of AI for personalized feedback, 3–5. Identification of biases in AI source data, 3–6. Risks associated with student use of AI, 3–7. Impact of AI on student data usage, 3–8. Ethical considerations in the technological use of AI, and 3–9. AI adoption among educators.

Area 4. Assessment: This domain focuses on the use of AI technologies to support educators in evaluating student achievement, monitoring and analyzing performance data, and delivering timely, targeted feedback to foster academic progress. It includes the following variables: 4–1. Use of AI to enhance assessment strategies, 4–2. Mitigation of bias in assessment algorithms, 4–3. AI-induced learning bias in student evaluation, and 4–4. Limitations of AI in assessing social and interpersonal skills.

Area 5. Empowering students' AI learning: This area centers on the use of AI tools to improve student outcomes and deepen their engagement with AI-supported learning environments. It includes the following variables: 5–1. Design of customized AI learning systems, 5–2. Pedagogical benefits of AI personalization, and 5–3. Monitoring learning outcomes associated with AI use.

Area 6. Developing students' AI literacy: This final area promotes the innovative and responsible use of AI by students, with emphasis on key dimensions such as data privacy, intellectual property, ethical information use, content creation, well-being, and problem-solving. It includes the following variables: 6–1. Enrichment of learning through AI, 6–2. Use of AI to strengthen AI-related competencies, 6–3. Application of AI to enhance ethical awareness, and 6–4. Addressing biases through critical AI use.

As a result, the updated version of the DigCompEdu framework, adapted to AI competency, offers a structured and actionable approach for assessing and enhancing faculty digital proficiency in integrating advanced technologies into their professional practice. By employing this framework, institutions can identify developmental needs and support faculty in embedding AI into teaching and research, while simultaneously addressing ethical and operational challenges. Heard et al. (2024) emphasize the necessity of adopting comprehensive frameworks that consider both human and non-human dynamics, underscoring the complexity of AI-driven transformations in education. Similarly, Omar et al. (2024) stress the importance of tackling faculty concerns about data privacy and algorithmic bias, which are essential for building trust and promoting the effective adoption of AI in higher education.

Theoretical frameworkGrounded in human capital theory (Becker, 1962) and stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984), this research emphasizes the importance of faculty as a critical resource whose competency in AI can enhance the effectiveness of HEIs.

AI integration in higher education through the lens of human capital theoryHuman Capital Theory argues that investments in education and skill development yield benefits for both individuals and society by boosting productivity and fostering economic growth (Becker, 1962, 1994). Within HEIs, this framework supports the prioritization of equipping educators and students with AI-related competency. Enhancing educators’ AI capabilities, given their central role in the educational process, directly contributes to the formation of human capital (Santos Villalba et al., 2024).

Universities are increasingly aware that technology, in the absence of skilled users, constitutes an ineffective investment, which has prompted the implementation of training programs aimed at developing AI-specific competency (Azevedo et al., 2024). These initiatives constitute intentional investments in human capital, aligning faculty skills with institutional objectives and broader socio-economic mandates (Cazzaniga et al., 2024). As hubs of research, teaching, and innovation, HEIs confront both pedagogical and structural challenges in their digital transformation (Aparisi-Torrijo et al., 2024). Faculty upskilling through AI integration (whether in pedagogy, ethics, or learning environment design) has become a strategic imperative for institutional competitiveness. However, the rapid evolution of technological tools heightens the risk of skill obsolescence, reinforcing the imperative for continuous professional development (De Obesso et al., 2023; Nascimbeni et al., 2019). By strengthening educators’ digital competency, HEIs can improve learning outcomes, especially in areas such as creativity, entrepreneurship, and technological fluency (Dias-Trindade et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2021).

At the same time, Human Capital Theory provides a rationale for the role of HEIs in preparing students for labor markets increasingly shaped by automation and AI. Initiatives that embed algorithmic and digital literacy across academic disciplines enhance students’ ability to succeed in an AI-driven economy (Fowler, 2023; Oeldorf-Hirsch & Neubaum, 2023). This dual investment, in both educators and students, embodies a systemic approach to human capital development, with faculty serving as agents of transformation and students as its long-term beneficiaries.

HEIs also play a critical role in shaping educational and ethical frameworks for AI adoption by aligning integration strategies with principles of sustainability, equity, and the public mission of higher education (Schwaeke et al., 2025). Educators, as key institutional actors (Chapleo & Simms, 2010), play a central role in the implementation of these strategies in pedagogical practice. Digitalization, therefore, entails not only technical adaptation but also a reconfiguration of teaching paradigms, requiring faculty who are both technologically proficient and pedagogically innovative. However, there is limited empirical research on how university educators’ AI competency development directly affects student learning outcomes, leaving a gap in understanding the broader human capital implications of AI integration.

Taken together, these observations support the following hypothesis: the development of faculty competency in AI functions as a foundational driver of institutional adaptation and student preparedness for AI-transformed economies. Anchored in Human Capital Theory, this hypothesis is substantiated by the dual effect of faculty upskilling: it not only increases educators’ productivity but also facilitates the formation of graduates equipped to contribute meaningfully to dynamic labor markets. Accordingly, the technological readiness of both faculty and students emerges as an intentional outcome of institutional human capital strategies.

Higher education institutions' strategic approach to faculty as main stakeholdersStakeholder Theory conceptualizes organizations as entities embedded within complex environments composed of multiple actors who possess distinct interests, varying degrees of influence, and legitimate claims on organizational outcomes (Freeman, 1984; Freeman & McVea, 2005). In contrast to shareholder-centric models, it advocates for inclusive governance that responds to the expectations of diverse stakeholders. Consequently, institutional effectiveness is contingent upon the ability to manage competing demands while preserving legitimacy, ensuring transparency, and fostering long-term value creation (Freeman et al., 2007; Porter & Kramer, 2011).

In the context of HEIs, the relevance of Stakeholder Theory is particularly pronounced, given the significant role played by students, faculty, employers, governments, and communities in shaping institutional strategy and identity (Langrafe et al., 2020; Chapleo & Simms, 2010). The ongoing digital transformation further intensifies the complexity of governance and decision-making processes (McCarthy et al., 2023). Within this evolving landscape, faculty emerge as pivotal stakeholders due to their active engagement in teaching, research, and institutional responsiveness to change (Langrafe et al., 2020; Mah & Groß, 2024).

Despite their strategic role, many HEIs lack comprehensive frameworks to prepare faculty for emerging technological challenges such as artificial intelligence. This gap undermines their ability to integrate AI into teaching, research, and service, thereby constraining institutional responsiveness to societal needs (Sued, 2022). Addressing this challenge requires specialized training in adaptive learning, automated assessment, and data-driven instructional design, as well as ethical frameworks that ensure alignment with institutional values and the public interest (Ciarra Tejada & Parra Sánchez, 2024).

In competitive academic environments, the strategic management of faculty development is critical to institutional resilience and strategic positioning (Bernardi et al., 2019; Forliano et al., 2021). Programs focused on technological and pedagogical innovation improve educational quality, graduate employability, and societal engagement (Langrafe et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2024). Without structured mechanisms for adaptation, HEIs are at risk of stagnation. Recent research highlights the value of strengthening faculty digital competency through open innovation strategies and the incorporation of external knowledge to enhance teaching and institutional development (Jekabsone & Anohina-Naumeca, 2024).

Applying Stakeholder Theory to the governance of HEIs requires acknowledging faculty as agents of transformation. Engagement models, such as those implemented at the University of Portsmouth, illustrate the benefits of collaborative decision-making for fostering innovation and enhancing institutional responsiveness (Chapleo & Simms, 2010). In the context of AI, this recognition must be translated into capacity-building initiatives and resource allocation that enable faculty to act effectively. Faculty development, when integrated as a governance strategy, strengthens institutional capacity to address external challenges and contributes to broader societal and economic goals (Syed et al., 2024).

Integrating Stakeholder Theory and Human Capital Theory provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the strategic role of faculty in HEIs. Stakeholder Theory highlights their legitimacy and influence in shaping institutional strategies, while Human Capital Theory emphasizes targeted investment in faculty competency as a driver of productivity, innovation, and institutional relevance. Although both frameworks stress the centrality of faculty in ongoing digital and pedagogical transformation, most studies examine these dimensions separately. This reveals a research gap regarding the combined analysis of faculty development as both a strategic investment and a stakeholder engagement imperative. Closing this gap is essential for aligning HEIs’ internal development strategies with governance demands and societal objectives in contexts of technological change.

Based on this integrative framework, this study examines the extent to which professors’ competency and attitudes toward AI enhance student learning. It aims to identify actionable strategies for aligning faculty development with institutional goals, ensuring that investments in human capital and stakeholder collaboration translate into long-term educational and societal impact. Accordingly, the research gap is articulated in the following question: How do professors’ competency and attitudes toward AI contribute to student learning in the context?

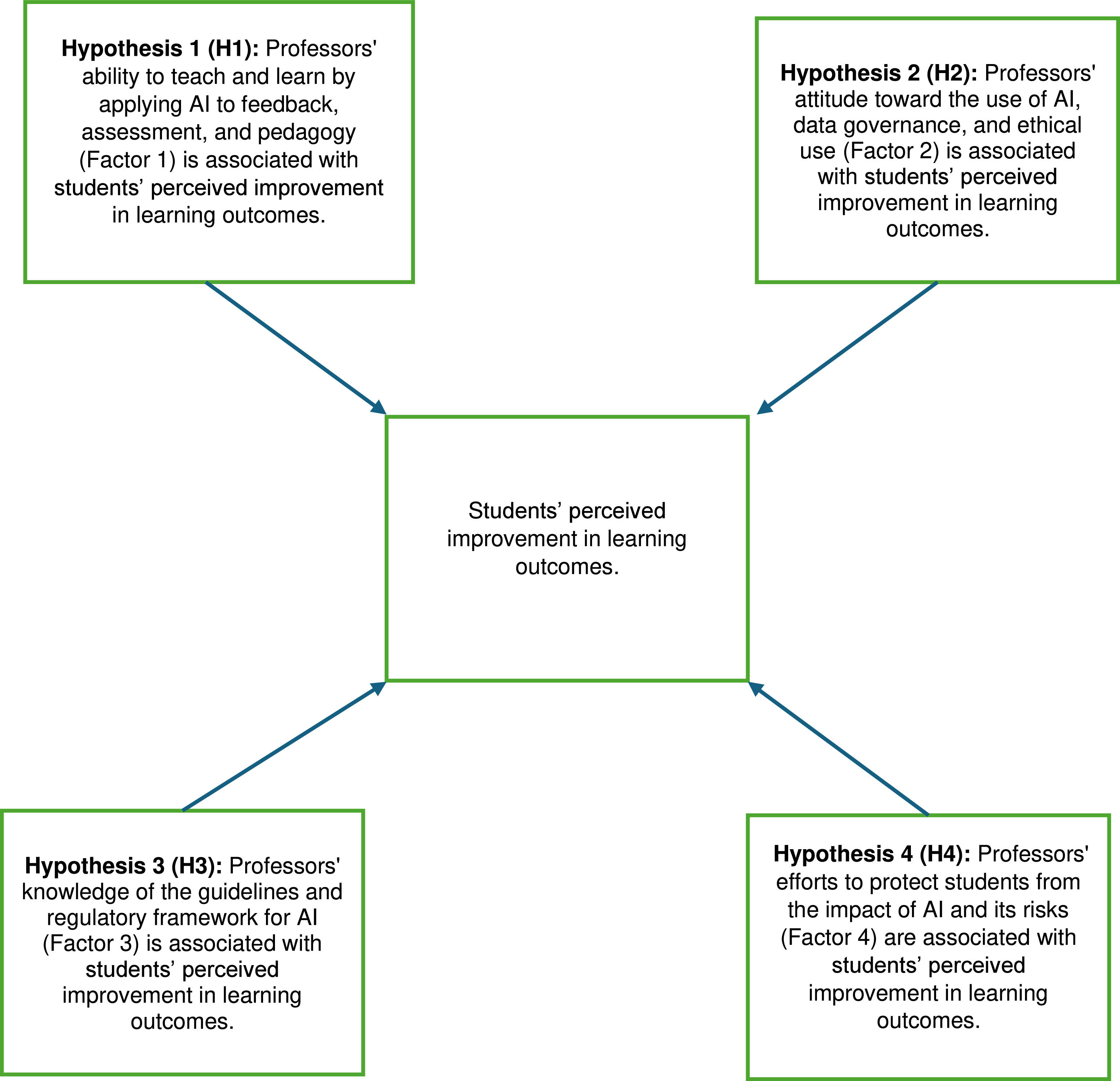

Building on these theoretical foundations, four hypotheses are proposed to examine the relationship between professors’ AI competency and students’ perceived learning improvement:

Hypothesis 1H1 Professors' ability to apply AI in feedback, assessment, and pedagogy is associated with students’ perceived improvement in learning outcomes.

Hypothesis 2H2 Professors' attitudes toward AI, data governance, and ethical use are associated with students’ perceived improvement in learning outcomes.

Hypothesis 3H3 Professors' knowledge of AI guidelines and regulatory frameworks is associated with students’ perceived improvement in learning outcomes.

Hypothesis 4H4 Professors' efforts to protect students from AI-related risks are associated with students’ perceived improvement in learning outcomes.

These hypotheses provide the basis for empirical testing through the adaptation of the DigCompEdu framework to AI-related digital competency (See Fig. 1).

Materials and methodsResearch designTo test the hypotheses of the model in this research, an adapted DigCompEdu questionnaire on AI-related digital competency, inspired by the well-recognized work of Ng et al. (2023), has been used (see Annex). A 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 6 is used to assess all items. The DigCompEdu questionnaire, adapted by Ng et al. (2023), is an instrument comprising 35 items organized into six areas of AI use in teaching. Four additional items have been added to analyze the variables of interest, and one dependent variable item (Q4) has also been incorporated.

Q1 Howwould you rateyour current use of artificial intelligence (AI)? Assign a proficiency level of 1 to 6, with 1 being the lowest and 6 being the highest.

Q2 How would you describe your attitude towards the use of AI tools in your teaching? [They may (1) distort your work as a teacher; (2) hinder and limit students' learning (3) boost your opportunities as a teacher](being 1 meaning “nothing” and 6 “a lot”)

Q3 To what extent do you think your institution is helping to prepare teachers in the use of AI tools? (being 1 meaning “nothing” and 6 “a lot”)

Q4 To what extent do you think the use of AI tools improves student learning? (being 1 meaning “nothing” and 6 “a lot”)

The dependent variable Q4 is a single item representing an educational outcome. In the economics of education literature, there is a long tradition of using single items to capture complex constructs, including learning outcomes (Kifle, 2025). To address the complexity of the factors, first applied factor analysis was first applied, followed by a causal analysis using a regression model.

The data were collected from 105 anonymous respondents and carefully analyzed. To obtain a large and heterogeneous pool of university business and economics professors in the absence of a comprehensive sampling frame, chain-referral (snowball) sampling was employed, a non-probability method in which initial respondents recruit others from their networks, thereby expanding coverage while maintaining some control over the sample’s composition by launching multiple seeds and monitoring referral growth (Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981). Data collection took place between November and December 2023. Invitations were distributed via email, LinkedIn, and WhatsApp, following this procedure. The questionnaire was administered in Spanish and subsequently translated into English to meet publication requirements.

The sample consists of 62.9 % men and 37.1 % women. Of these, 68.6 % have teaching as their main activity. In terms of qualifications, 37.1 % hold a bachelor’s degree or an equivalent professional qualification (architecture, engineering, or medicine), 21 % hold a doctorate, and 20.1 % hold a doctorate together with a teaching accreditation. In terms of classroom teaching experience, 18.1 % have between 1 and 5 years of experience, 14.3 % have between 6 and 10 years, 17.1 % have between 11 and 15 years, 18.1 % have between 16 and 20 years, 11.4 % have between 21 and 25 years, and 21 % have >25 years of teaching experience. Regarding online teaching experience, 67.6 % have between 1 and 5 years, 21.9 % between 6 and 10 years, 5.7 % between 11 and 15 years, 1.9 % between 16 and 20 years, and 2.9 % have >25 years of online teaching experience.

To ensure the integrity and confidentiality of the information, all relevant ethical considerations were addressed to guarantee the anonymity of the data and to comply with regulations on data use, approval procedures, transparency, and the compliance requirements of the participating universities. The information collected was then analyzed using statistical techniques to provide a detailed understanding of the research question and to highlight the importance of AI competency among educators.

ResultsThe analysis of educators’ self-assessments based on the DigCompEdu framework provides important insights into AI adoption in education. Professors rated their AI proficiency in Q1, with 61 % placing themselves at a low level (from novice to integrator, 1 to 3). This points to a substantial skills gap and underscores the need for targeted interventions to support effective AI integration. The urgency of this need is reinforced by earlier findings: prior to the introduction of ChatGPT, only 37.5 % of professors reported low digital competency in the same context (Núñez-Canal et al., 2022). This contrast suggests that, although general digital skills have improved, educators still struggle to adapt to AI tools, in part due to the accelerated digitalization triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic.

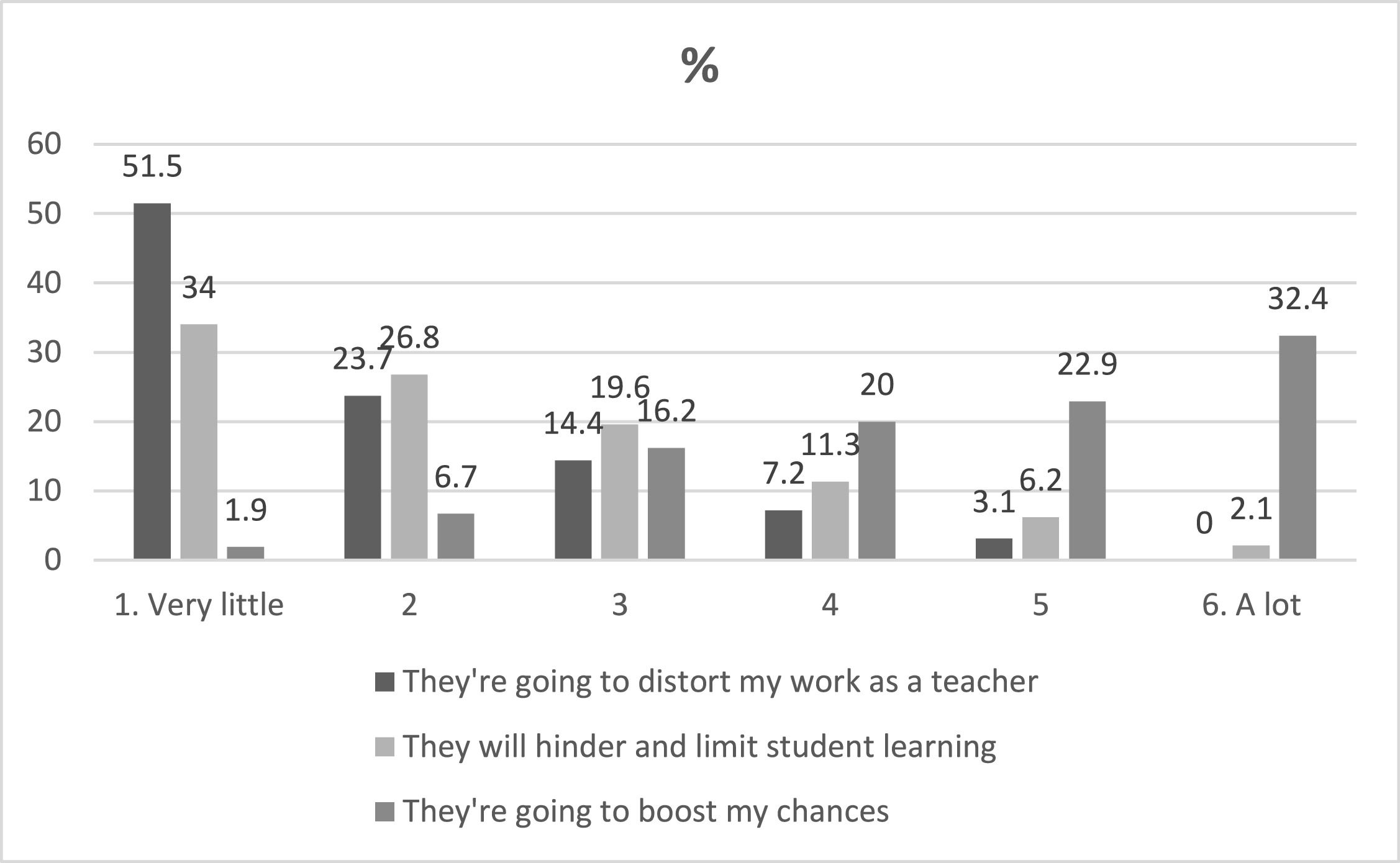

Educators were asked in Q2 about their attitudes toward using AI in teaching, and the results revealed a mixed but informative picture. Approximately 55.3 % believed that AI could enhance their pedagogical practice (see Fig. 2), reflecting optimism regarding its potential to improve teaching. Moreover, 51.5 % expressed confidence that AI could coexist with their teaching role without undermining their professional responsibilities.

However, 60.8 % were concerned that AI might negatively affect student learning. This ambivalence reflects both optimism about AI’s potential and caution regarding unintended consequences. These findings highlight the need to address educators’ concerns while at the same time strengthening their confidence in AI tools in order to support their meaningful integration into teaching.

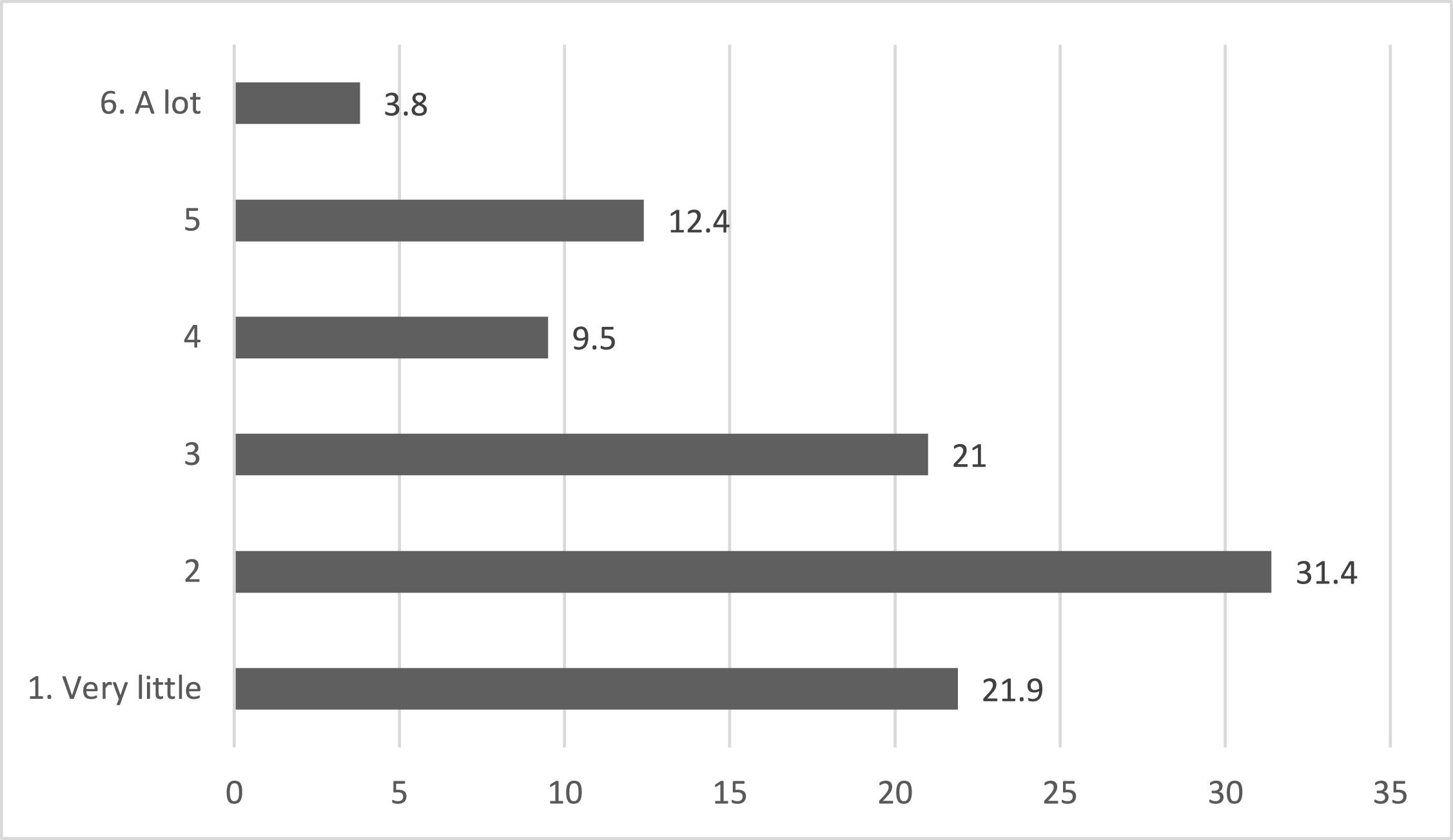

When asked in Q3, "To what extent do you think your institution is helping to prepare teachers for the use of AI tools?" educators reported a clear gap between expectations and the support received. A total of 74.3 % felt their institution provided only minimal or moderate support, while just 3.8 % felt fully supported (see Fig. 3). These findings reveal a significant shortfall in institutional strategies aimed at equipping educators with the competency required to remain competitive in the higher education landscape, fulfill their social mission, and effectively address the expectations of key stakeholders. The lack of robust support undermines educators' capacity to integrate AI meaningfully into their teaching and jeopardizes institutions’ ability to adapt to technological advancements, meet societal demands, and maintain their legitimacy in developing the human capital needed for an AI-driven economy.

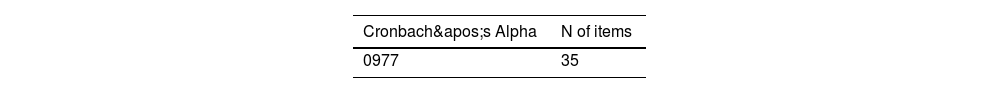

After an initial descriptive analysis, factor analysis and regression analysis were conducted on the 35 survey items to identify the main factors influencing educators’ performance in the use of AI across the areas defined by the DigCompEdu model. Subsequently, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated to assess the instrument's reliability (see Table 2). The resulting value (α = 0.977) indicates a very high level of reliability, clearly exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 0.80.

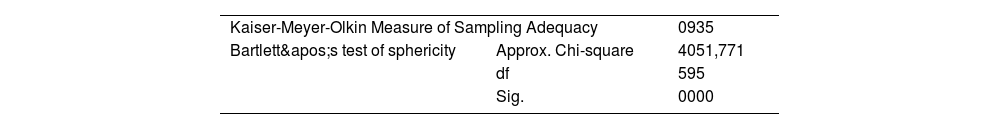

A factor analysis was conducted to evaluate the validity of the model and of the scales used to measure the six areas and 35 variables of the DigCompEdu instrument. A preliminary examination of the data indicated that they were suitable for this type of analysis, as the correlation matrix showed correlation coefficients above 0.30 for most item pairs. The data were processed using SPSS software. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy yielded a high value of 0.935 (see Table 3). In addition, Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant (p = 0.000), which is below the 0.05 threshold and therefore indicates that the null hypothesis of sphericity can be rejected and that the factor model provides an adequate fit to the data.

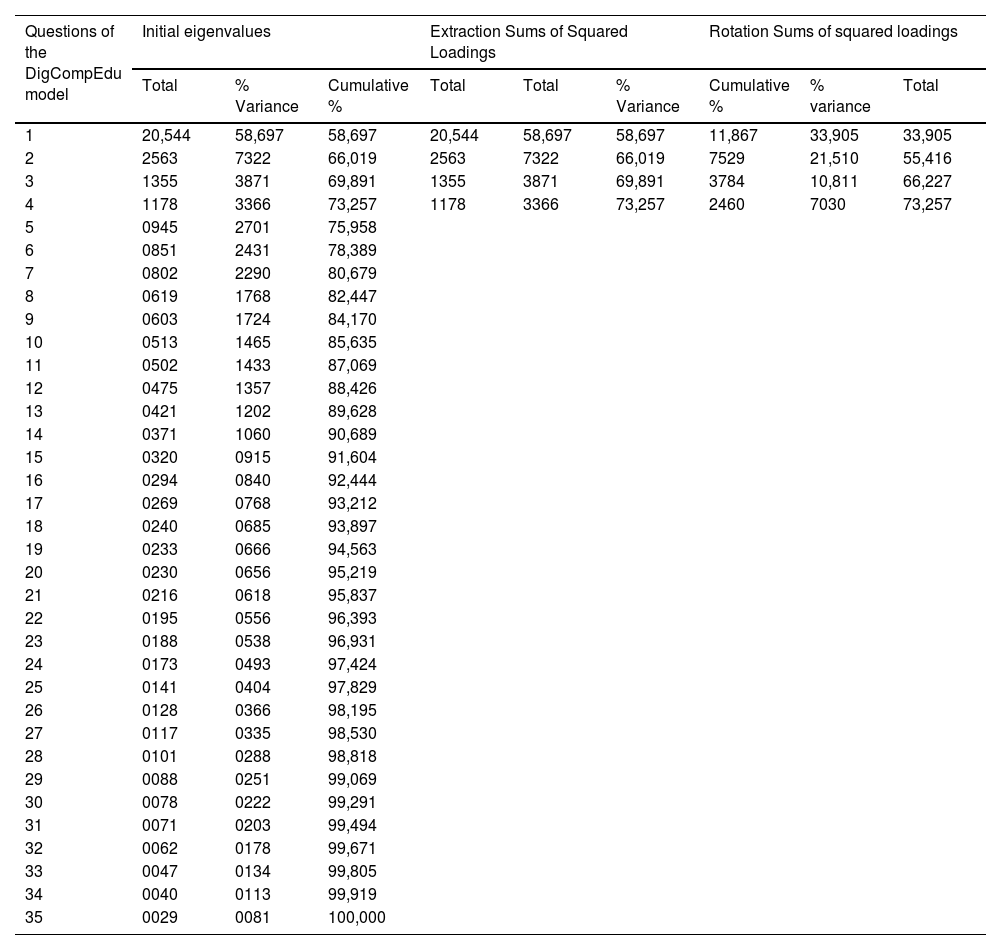

Based on the initial theoretical proposal, factor analysis was conducted using the principal components method, with varimax rotation and Kaiser normalization. For item selection, items whose values exceeded 0.535 were eliminated. The results indicated that the variables were grouped into four factors, which together explained 73.257 % of the variance in the model (see Table 4

Four sets of variables explain a high percentage of the model's variability.

Source: Prepared by the author.

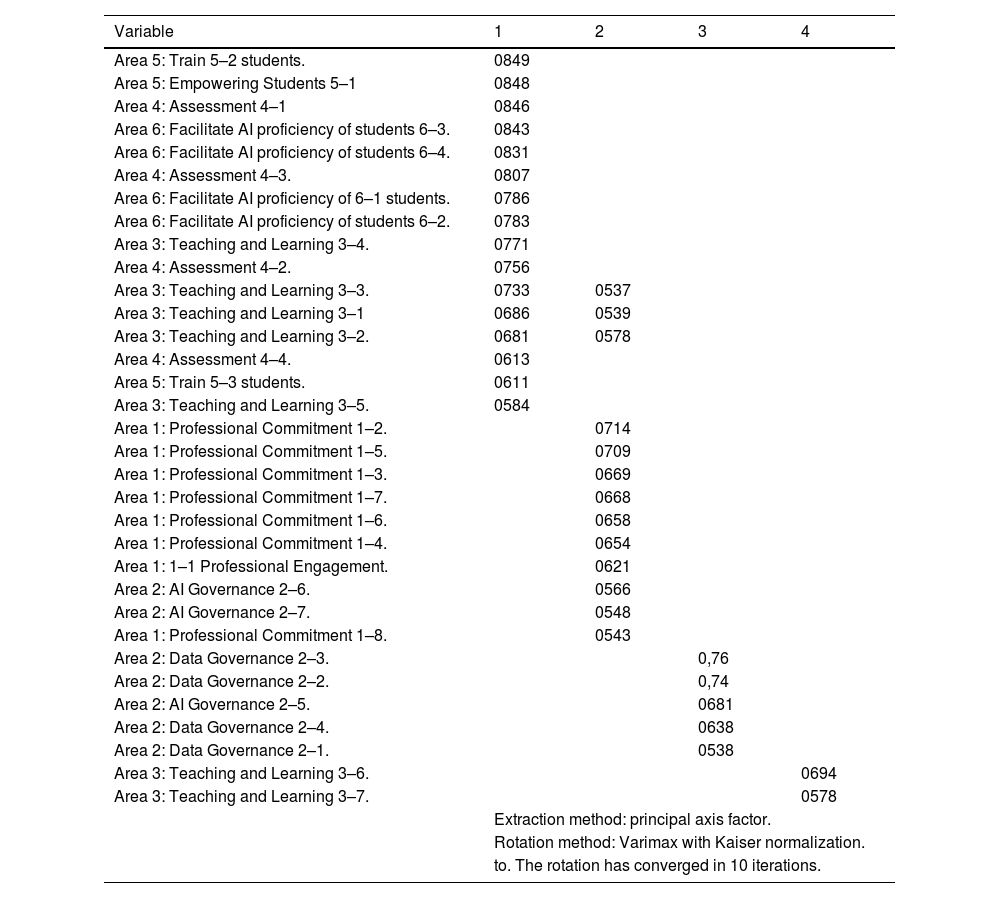

Table 5 below shows how the four factors influence the variables in the model through a Rotated Factor Matrix.

Influence of the variable of the model by Rotated Factor Matrix.

Source: Prepared by the author.

As a result, the 35 variables of the DigCompEdu instrument are grouped into four factors that are defined as follows:

Factor 1: Teaching and learning

Factor 2: Attitude toward the use of AI, data governance, and ethical use.

Factor 3: Knowledge of the guidelines and regulatory framework for AI

Factor 4: Protecting students from the impact of AI and its risks

These factor-analytic results offer a new perspective on the DigCompEdu theoretical framework, synthesizing the six dimensions of the original model into four factors, as outlined in the literature review: (1) the use of AI for pedagogy and feedback, (2) attitudes toward ethical use and data governance, (3) knowledge of regulatory frameworks, and (4) efforts to mitigate risks associated with AI adoption. This configuration represents a substantive contribution to the adaptation of the DigCompEdu model for use by HEIs and policymakers.

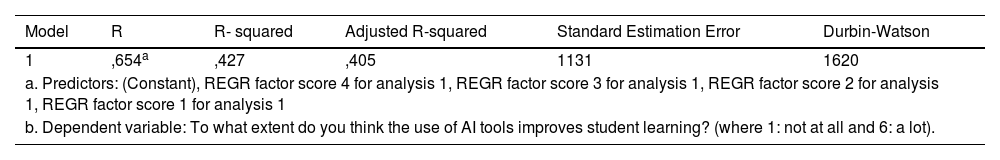

Hypothesis confirmation for model variablesThe validation of the hypotheses was carried out following the factor analysis, using linear regression models. Examination of the four standard assumptions implied that the models employed in this study satisfied the required conditions and that none of these assumptions appeared to be violated in isolation. In this context, the value of the Durbin–Watson statistic is 1.620 (see Table 6), which indicates that the linear regression model meets the criteria of independence, normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity.

Model Summary. The linear regression model meets the criteria of independence, normality, linearity and homoscedasticity.

Source: Prepared by the author.

The dependent variable in the model is: “To what extent do you think the use of AI tools improves student learning?” (where 1 = not at all and 6 = a lot). The validation of the hypotheses is performed jointly for the factors derived from the factor analysis.

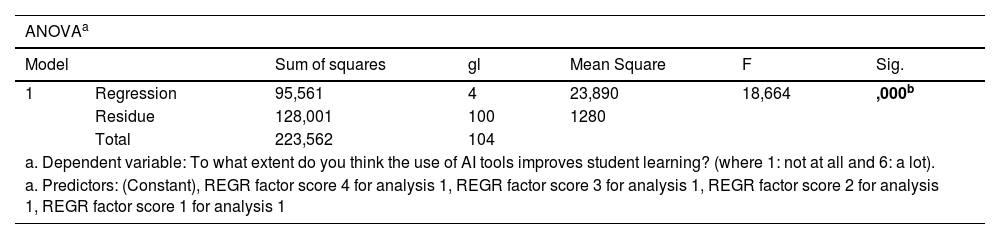

The F-statistic is used to test whether there is a significant linear relationship between the dependent variable and the independent variables in the model. Specifically, it tests the null hypothesis that the value of the multiple correlation coefficient (R) is zero in the population. With a critical level of Sig. = 0.000, there is a significant linear relationship in the four models studied. Accordingly, the regression equation can be considered to provide an adequate fit to the data. For more details, see Table 7, where the results of the ANOVA are presented.

ANOVA. There is a significant linear relationship between the four models studied.

Source: Prepared by the author.

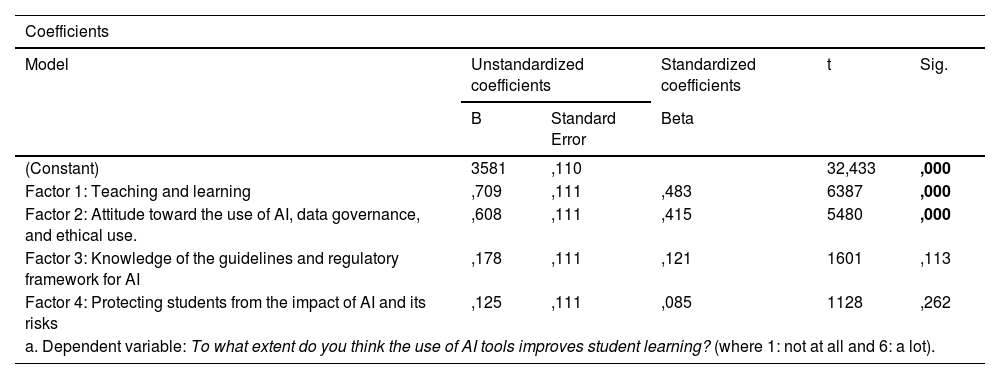

Finally, a regression model was conducted to confirm the model's results, as presented in Table 8.

Hypothesis confirmation table.

Source: Prepared by the author.

Based on the results of the regression model, not all variables show a statistically significant relationship with the dependent variable. Factors 1 and 2 present significance levels below 0.05, indicating that the null hypothesis is rejected for these factors and that there is a linear relationship between these independent variables and the dependent variable. Specifically, Factor 1, Teaching and learning, has the strongest influence (B = 0.709, Beta = 0.483, p < 0.001), followed by Factor 2, Attitude toward the use of AI, data governance, and ethical use (B = 0.608, Beta = 0.415, p < 0.001).

In contrast, Factor 3, Knowledge of the guidelines and regulatory framework for AI (p = 0.113), and Factor 4, Protecting students from the impact of AI and its risks (p = 0.262), do not reach statistical significance at the 0.05 level, suggesting that their coefficients are not statistically different from zero in this model.

Taken together, these findings indicate that teaching practices and attitudes toward AI positively influence the perception that AI tools enhance student learning, thereby confirming Hypotheses 1 and 2. However, knowledge of regulatory frameworks and measures to protect students from AI-related risks do not appear to affect perceived learning, which leads to the rejection of Hypotheses 3 and 4.

DiscussionThe results of this study provide significant insights into the relationship between educators' competency and attitudes toward AI, as well as the factors influencing their integration of AI tools in HEIs. These findings align with and expand upon the concepts outlined in the theoretical framework. From the perspective of Human Capital Theory, the results demonstrate that investment in faculty digital and AI competency is essential to enhance productivity, prepare students for AI-driven labor markets, and build a more democratic and inclusive society based on liberal values. This is not merely an assumption, but a conclusion that aligns with the major trends in AI system implementations in education, AI ethics, and studies on regulatory frameworks and AI literacy, such as Stracke et al. (2025). From the standpoint of Stakeholder Theory, the results highlight the centrality of educators as primary stakeholders, whose engagement is critical to legitimizing institutional strategies and fulfilling the broader mission of HEIs.

In response to the question on AI-related digital competency (Q1, see Methodology), 61 % of educators rated their AI proficiency between novice (1) and integrator (3). This significant skills gap reflects the urgent need for targeted training programs. It also corroborates previous studies showing deficiencies in digital competency (Núñez-Canal et al., 2022; Rahimi & Tafazoli, 2022) but suggests that the challenge is now more acute with AI-specific skills (Fengchun & Holmes, 2023). From a Human Capital perspective, such deficiencies hinder the ability of educators to act as drivers of knowledge and innovation (Brey & van der Marel, 2024; Jimeno & Lamo, 2024). Structured, accessible training tailored to AI competency is therefore critical (Celik et al., 2022).

Regarding attitudes (Q2), 55.3 % of educators believe that AI can enhance their pedagogical skills, while 51.5 % are confident that AI can coexist with their teaching roles. These findings resonate with prior research by Meirbekov et al. (2022) and Omar et al. (2024), which emphasize the importance of educators’ attitudes in shaping AI adoption and confirm Stakeholder Theory’s assertion that educator engagement directly influences institutional legitimacy and success (Ghomi & Redecker, 2019; Abbasi et al., 2025). However, the study also highlights considerable apprehension, with 60.8 % of participants expressing concerns that AI might negatively affect students’ learning experiences, which is consistent with recent studies on the impact of AI tools on students’ critical thinking (Gerlich, 2025) and ethics (Bond et al., 2024; Fowler, 2023; Mumtaz et al., 2024). This ambivalence reflects the ethical and practical challenges outlined by Bond et al. (2024), Mumtaz et al. (2024), including data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the potential erosion of critical thinking skills among students. These concerns point to the need for a human-centric approach (Cardona et al., 2023; Fengchun & Holmes, 2023; Molina et al., 2024) to technological integration and the safeguarding of educational values and the role of faculty as guardians of those values (Ciarra Tejada & Parra Sánchez, 2024).

The question on institutional support (Q3) revealed a mismatch between faculty expectations and institutional strategies, which makes this issue a key concern for the management transformation of HEIs (George & Wooden, 2023). While 74.3 % of respondents reported receiving minimal or moderate institutional support for AI training, only 3.8 % felt fully supported. Segbenya et al. (2024) emphasize that robust institutional policies and resource allocation are crucial for fostering faculty adoption of AI. The lack of comprehensive support risks not only undermining educators’ capacity to integrate AI effectively but also eroding the institution’s ability to maintain competitiveness (George & Wooden, 2023) and fulfill its educational and societal responsibilities (Msambwa et al., 2025). This can also affect the mission of universities as drivers for innovation and entrepreneurship in society (Jekabsone & Anohina-Naumeca, 2024). From a Stakeholder perspective, this weakens trust and legitimacy, while from a Human Capital perspective, this gap represents a missed opportunity for HEIs to invest in their most critical resource—their faculty—to drive both institutional resilience and societal advancement (Walter & Lee, 2022).

The regression analysis underscores the importance of specific factors in shaping educators’ perceptions of AI’s impact on student learning. Factor 1, related to teaching and learning, and Factor 2, capturing attitudes toward AI, data governance, and ethical use, both emerged as statistically significant predictors of perceived learning improvement. This finding is consistent with previous studies that identify educators’ attitudes as a key determinant of the success of technology integration (Ghomi & Redecker, 2019; Rahimi & Tafazoli, 2022; Torrato et al., 2020) and, more specifically, of AI adoption in higher education (Abbasi et al., 2025; Omar et al., 2024). Educators who combine the necessary competency with a positive disposition toward AI are more likely to adopt innovative methodologies, promote critical thinking, and uphold ethical practices, thereby enhancing student learning outcomes.

By contrast, Factors 3 and 4 (knowledge of regulatory frameworks and efforts to mitigate AI-related risks) did not reach statistical significance. A plausible interpretation is that these dimensions are more distal to day-to-day teaching practice. Although regulatory awareness and safeguarding competency are essential for responsible AI use, they do not necessarily translate into observable changes in instructional design or immediate learning gains in the classroom. From a Stakeholder Theory perspective (Freeman, 1984), this distinction is particularly relevant. Governance structures must ensure compliance and protection, responding to the expectations of policymakers, institutions, and families, without unduly constraining pedagogical innovation, which primarily benefits students and educators. Responsible governance should therefore balance the demands of multiple stakeholder groups: it must safeguard ethical use while creating enabling conditions for AI to support teaching and learning effectively. In this sense, even if these factors do not directly influence perceptions of AI’s impact on learning, they constitute crucial contextual conditions for institutional trust, accountability, and ethically grounded AI integration (Fengchun & Cukurova, 2024; Mah & Groß, 2024; Villegas-José & Delgado-García, 2024; Abbasi et al., 2025; Cardona et al., 2023; McCarthy et al., 2023; Mumtaz et al., 2024).

The analyses conducted confirm that both professors’ ability to mobilize AI in teaching and learning—through feedback, assessment, and pedagogy (H1)—and their attitudes toward AI use, data governance, and ethical considerations (H2) are significantly associated with perceived improvements in student learning. In contrast, no statistically significant relationship was found between educators’ knowledge of AI policies and regulatory frameworks (H3) or their efforts to protect students from AI-related risks (H4) and perceived learning enhancement. Taken together, these results suggest that technical-pedagogical competency and favorable attitudes toward AI are the primary drivers of successful integration, whereas broader regulatory knowledge and risk mitigation, although necessary for responsible governance, may require stronger institutional alignment and contextual support before their influence on learning becomes apparent.

These findings underscore the need for HEIs to adopt a dual, but integrated, approach to AI that simultaneously addresses its technical and ethical dimensions. Faculty training cannot be limited to operational mastery of AI tools; it must also incorporate AI literacy, data governance, and ethical reflection, as suggested by Ng et al. (2023). Only when educators understand not just how to use AI, but why, when, and under what conditions it is appropriate, can they make pedagogically sound and ethically robust choices. In this sense, comprehensive training programs do more than improve individual proficiency: they align institutional practices with the expectations of key stakeholders—students, employers, and policymakers—who increasingly demand both innovation and responsibility. By embedding these elements into faculty development, HEIs can position educators not as passive adopters of technology, but as informed leaders capable of shaping AI integration in line with educational values and societal needs.

The study also shows that Human Capital Theory and Stakeholder Theory, taken together, offer a particularly useful lens for understanding AI adoption in HEIs. Human Capital Theory explains why investments in faculty digital and AI competency are not a discretionary cost, but a strategic requirement for institutional competitiveness and student preparedness for AI-intensive labor markets. Stakeholder Theory, in turn, clarifies how faculty engagement and voice are essential for legitimizing AI-related strategies, ensuring that technological adoption is perceived as credible, fair, and aligned with the public mission of higher education. The combined framework advances the literature by explicitly linking investment in faculty competency (the human capital dimension) with the governance and relational dynamics that condition the acceptance and effectiveness of those investments (the stakeholder dimension)—an intersection rarely examined in depth in prior studies.

For universities, the implications are concrete. The design of structured faculty training programs in AI should integrate technical, pedagogical, and ethical components (Ng et al., 2023), rather than treating them as separate agendas. Aligning these programs with the guidelines of international organizations such as UNESCO (2023) and the World Economic Forum (2025) can help ensure that AI adoption contributes to equity, inclusion, and long-term sustainability, rather than merely to short-term efficiency gains. From a strategic management perspective, adopting an AI competency framework at the institutional level would allow HEIs to guide and prioritize investments in human capital, connect training to actual AI use in courses, and monitor progress through explicit measurement systems. Such measurement is essential for improving institutional effectiveness and for demonstrating accountability to external stakeholders. Policymakers, for their part, should support HEIs by funding these capacity-building efforts and by providing flexible, enabling regulatory frameworks that safeguard rights and ethical principles while leaving room for pedagogical innovation.

ConclusionsThis study advances the understanding of AI integration in higher education by providing empirical support for the joint explanatory value of Human Capital Theory and Stakeholder Theory in this context. The results indicate that educators’ competency and attitudes toward AI are significantly associated with perceived improvements in student learning, whereas institutional support is perceived as insufficient to enable systematic and meaningful adoption. Within the scope of this research, and by explicitly linking survey evidence (Q2–Q4) to these theoretical frameworks, the findings substantiate the dual role of faculty: they function both as strategic investments in human capital—whose skills and dispositions are critical for educational performance—and as central organizational stakeholders, whose engagement conditions institutional legitimacy, adaptability, and competitiveness in AI-intensive environments.

The originality of this research lies in the adaptation of the DigCompEdu framework to the domain of AI, resulting in an analytically grounded instrument for assessing faculty preparedness across pedagogical, ethical, and governance dimensions. This revised framework not only refines existing models of digital competency but also provides a systematic basis for evaluating educators’ readiness in AI-enhanced teaching and learning settings. Conceptually, the study contributes to the literature by integrating human capital and stakeholder perspectives into a single analytical lens, a combination rarely operationalized in empirical work on AI in higher education. Practically, the findings point to a clear course of action: universities and policymakers should design structured, evidence-based faculty development programs in AI that are aligned with international recommendations (UNESCO, 2023; World Economic Forum, 2025) and that deliberately promote both technical proficiency and ethical responsibility. By doing so, higher education institutions can position faculty as informed and empowered agents of responsible AI adoption, fostering innovation while preserving and reinforcing core educational values.

Limitations and further researchThis study is subject to several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, its focus on a specific population of business and economics faculty constrains the generalizability of the results to other disciplines, institutional types, and higher education systems. Second, the reliance on self-reported data may introduce social desirability and perception biases in the assessment of competency and attitudes toward AI, potentially leading to over- or underestimation of actual proficiency and dispositions. Third, although the adapted DigCompEdu framework offers a structured and analytically robust tool for examining AI-related skills, it may not fully capture all dimensions of faculty readiness in rapidly evolving technological and regulatory environments.

In addition, the analysis is restricted to educators’ perspectives and does not incorporate the views of other key stakeholders, such as students, institutional leaders, or employers, which are central to a stakeholder-based understanding of AI integration in HEIs. Future research should therefore adopt multi-stakeholder designs, compare results across regions, disciplines, and institutional profiles, and employ mixed methods or longitudinal approaches to examine the long-term effects of faculty AI training on student learning, organizational change, and institutional performance. Such work would deepen the evidence base on responsible AI integration in higher education and provide a more comprehensive account of its contribution to human capital development.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMargarita Núñez-Canal: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. María de las Mercedes de Obesso Arias: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Carlos Alberto Pérez-Rivero: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ignacio Álvarez-de-Mon: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Resources, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.