Internal innovation contests are the most frequently realized practical approach to capturing organization-wide creativity. Here, important business challenges are digitally broadcasted to a large group of potential volunteers within the firm regardless of their position. Innovation theory highlights that positive perceptions of individuals’ work environment positively influence their innovating behaviors, while negative perceptions suppress them. We surveyed employees of a specific subsidiary of a large German company in the telecommunications industry that is responsible for the management of the group's entire product portfolio. The results indicated that (1) not all elements of the work environment influence employees’ intrinsic motivation to participate and (2) power distance orientation matters when intrinsic motivation leads to willingness to participate in future internal idea contests.

In their efforts to come up with innovative product and service ideas, many firms have started not only to draw upon research and development, as well as marketing departments but also to include a wider variety of the organizational workforce in their innovation processes (Adamczyk, Bullinger, & Möslein, 2012; Whittington, Cailluet, & Yakis-Douglas, 2011; Zhu, Kock, Wentker, & Leker, 2019; Zuchowski, Posegga, Schlagwein, & Fischbach, 2015). In particular, core inside innovators, who were once solely responsible for idea generation in many companies, are now complemented by so-called peripheral inside innovators, whose primary job usually does not involve innovation-related activities (Neyer, Bullinger, & Moeslein, 2009). The underlying rationale of this strategy is quite simple: creativity and the resulting ideas of experts are bounded, and non-experts might bring in fresh perspectives, at least in the idea generation phase (Poetz & Schreier, 2012). To more structurally assess and capture ideas spread among the entire organization, many firms have started to use idea management software to support innovation activities (Piller & Walcher, 2006; Sandstrom & Bjork, 2010). Consequently, industry leaders in various sectors such as Deutsche Telekom (telecommunications), BASF (chemicals), and ThyssenKrupp (steel and components technology) have such idea management systems in place. The business press and academics alike regularly report on the success of these innovation initiatives. For example, according to a Wall Street Journal Blog entry, AT&T received approximately 28,000 ideas between 2009 and 2014 through their idea management system and has allocated $44 million to fund promising ideas (King, 2014). Typically, firms use idea management systems, in which they implement one or more idea contests that belong to the same innovation initiative (Elerud-Tryde & Hooge, 2014). These initiatives contain multiple individual idea contests and are designed to focus on a particular given problem. Thus, employees do not submit any idea that just came to their mind; all ideas have to be related to the initiative.

Most prior research on individual motivation for idea contests and crowdsourcing for ideas has focused on an outside-in perspective, that is, on factors that motivate people external to the firm to participate in such contests in an open innovation context (e.g., Fueller, Hutter, Hautz, & Matzler, 2017; Hofstetter, Zhang, & Herrmann, 2018; Hutter, Hautz, Fueller, Mueller, & Matzler, 2011; Rauter, Globocnik, Perl-Vorbach, & Baumgartner, 2018). Insights stemming from these types of research are important to design external innovation contests in ways that a sufficient number of (good) ideas emerge. In contrast, research on motivational drivers for internal idea contests is comparatively scarce. One of the few exceptions is provided by Wendelken, Danzinger, Rau, and Moeslein (2014), who found overlapping and distinguishing motivational structures for participants and non-participants in internal idea contests. For example, while career and reputation-related issues depict forms of external motivation for participants and non-participants alike, organizational atmosphere and arrangements are motivational factors for non-participants only. In a similar vein, in their recent review on internal crowdsourcing, a concept that goes beyond idea generation and includes concepts such as crowdsourced work, Zuchowski et al. (2015) identify several areas where future research is needed. This enumeration involves clarifying employees’ roles in idea contests, the role of IT as an enabler, and a more structured consideration of incentives and employee motivation (Boss, Kleer, & Vossen, 2017; Zuchowski et al., 2015). These open questions hold for internal idea contests in particular, which, in contrast to open community-based crowdsourcing approaches, are “open only to individuals and groups within the organization” (Leung, van Rooij, & van Deen, 2014, p. 44). Thus, more research is warranted on why and when peripheral internal innovators contribute to (IT-mediated) idea contests.

In addition, while intrinsic and extrinsic motivation have identified as potential drivers of creative behavior such as participating in innovation contests (e.g., Amabile & Pratt, 2016), still many initiatives struggle to turn employee motivation to actual behavior (Zuchowski et al., 2015). Therefore, research should start investigating potential moderating effects for the motivation-behavior link in firm-internal idea contests. One such potential moderator is power distance perceptions, a concept that is related but not identical to organizational hierarchy.

Against this background, this research contributes to the literature on employees’ motivation to participate in internal idea contests by (1) unraveling the role of creativity-related work environment perceptions and (2) investigating the role of power distance perceptions. We draw upon the componential theory of creativity and innovation in organizations (Amabile, 1988) to develop a work environment-related framework of motivations to participate in innovation contests. Furthermore, as participation in idea contests is voluntary and typically not part of the work contract, it may be viewed as a form of unrewarded organizational citizenship behavior (Schaarschmidt, 2016). A well-known driver of various forms of citizenship behavior is individual power distance orientation (e.g., Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen, & Lowe, 2009), that is, the extent to which an individual accepts the unequal distribution of power in institutions and organizations (Farh, Hackett, & Liang, 2007). As idea contests (as a form of internal crowdsourcing) differ from both external crowdsourcing initiatives and hierarchy-based innovation work (Zaggl, Schweisfurth, Schöttl, and Raasch, 2018; Zuchowski et al., 2015), studying power distance orientation, which incarnates the concept of informal hierarchy (Schwartz, 1992), helps in further disentangling open approaches to organizational innovation that involve the entire organizational workforce (i.e., peripheral inside innovators) from traditional hierarchy-based approaches (Ferreira & Teixeira, 2018).

This research is important to innovation and management theory as well as for daily research and development (R&D) practices. From a theoretical point of view, this research is among the first that combines employees’ creativity-related work environment perceptions with participation intention. In addition, it bridges a gap in organization theory by discussing the role of power distance orientation for the success of firm-internal idea contests. For management practice, the results lead to important implications as to how to design firm-internal idea contests in a way that increases continuous participation by internal peripheral innovators. To organize these contributions, this research is structured as follows. First, we introduce the underlying theoretical anchorage of creativity-related work environment perceptions, intrinsic motivation, and power distance. Then, we derive our hypotheses. After we present our results, we close with a delineation of managerial and theoretical implications.

Context and theoretical backgroundContext: Firm-internal idea contestsTypically, firms can rely on three types of innovators (Neyer et al., 2009). First, firms may maintain an explicit R&D department where experts work on new product and service ideas. This group is referred to as core inside innovators (Neyer et al., 2009). Second, in an effort to open the innovation process to external sources, firms can rely on the entire group of outside innovators, that is, the full range of external partners such as customers (Schaarschmidt, Walsh, & Evanschitzky, 2018), users (Schemmann, Chappin, & Herrmann, 2017), retailers, suppliers, and competitors (West & Bogers, 2014). Finally, an often neglected group is peripheral inside innovators. These innovators are employees across all business units and departments within the organization who, from the perspective of the core R&D activities, sit at the periphery (Neyer et al., 2009).

Idea contests as an open call are mechanisms to get access to knowledge of innovators who are not at the core of R&D activities. Typically, these contests are either directed toward outside innovators, for example, by including a community of product and service users (Fueller, Hutter, Hautz, & Matzler, 2014) or peripheral inside innovators. Considering employees of the organization, idea management systems that enable idea contests may be viewed as an extension of classical employee suggestion systems. When idea contests are managed by means of IT systems, employee suggestions become social; that is, people can share, rate, and discuss ideas such that ideas can develop (Von Krogh, 2012). This social aspect makes idea contests a powerful tool to access problem-related knowledge of the entire, often distributed, workforce. However, in contrast to idea contests that target outside innovators, research remains anemic regarding the motivational drivers of peripheral inside innovators to continuously contribute to idea contests (Moretti & Biancardi, 2018; Wendelken et al., 2014).

Componential theory of creativity and innovationContributing ideas to an open call in internal idea contests requires a certain level of creativity (Zhu, Djurjagina, & Leker, 2014). For answering our research questions, we therefore draw upon the Componential Theory of Creativity and Innovation in Organizations (CTCIO). At its core, CTCIO highlights perceptions of employees’ work environment as determinants of creativity and innovation within an organizational setting, while creativity is defined as “the production of novel and useful ideas” (Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby, & Herron, 1996, p. 1155). The theory has its foundation in the 1970s and 1980s and was elaborated over the last 25+ years (Amabile & Pillemer, 2012). Central assumptions state that various aspects of the work environment exist that commonly form and adjust different work environment perceptions of employees, which ultimately have a strong impact on the level and frequency of employees’ creative behavior and motivation to work on creative tasks (Amabile, 1997; Amabile & Kramer, 2007). At the organizational level (representing innovation), the theory postulates the following organizational components: “organizational motivation to innovate” (i.e., the basic orientation toward innovation), “resources in the task domain” (i.e., people, funds, material resources), and “management practices” (i.e., skills and styles to positively influence creative outcomes) (Amabile, 1997, 1988; Crossan & Apaydin, 2010). At the individual level (representing creativity), the theory postulates “expertise” (i.e., skills in the domain), “creative-thinking skills” (i.e., the way of searching for new ideas), and “task motivation” (i.e., motivation to perform an activity) as predictors of creativity. The highest profitability of individual creativity/organizational innovation is reached at the intersection where the components overlap (Amabile, 1988). According to the theory, all individual components influence the process steps of idea generation in several ways (Amabile & Pillemer, 2012). To make work environment perceptions more assessable, Amabile and her colleagues split the organizational components into various perceptions. These are the perceptions of “organizational encouragement” (positive) and “organizational impediments” (negative) for the component organizational motivation to innovate. For the component resources, the perceptions “sufficient resources” (positive) and “workload pressure” (negative) are prevalent. Finally, the perceptions “supervisory encouragement,” “work group support,” “challenging work,” and “freedom” (all positive) form the component management practice. The distinction between organizational-level and individual-level creativity will guide our research as well as the different forms of individual perceptions.

Power distance orientation and organizational innovationApart from motivational aspects that are tied to the individual, structural aspects could affect when and how employees participate in company-wide idea contests. One aspect that reflects informal organizational structures is power distance orientation. Power distance is among the most frequently studied cultural values in organizational research as it is fundamental to all relationships in hierarchical organizations (Daniels & Greguras, 2014). It also affects various processes and their outcomes. In the pertinent literature, power distance orientation in general is defined as “the extent to which a society accepts the fact that power in institutions and organizations is distributed unequally” (Hofstede, 1980, p. 45). While this definition targets societal aspects, it has also been applied in organizational contexts (e.g., Farh et al., 2007). The acceptance of inequalities shapes employees’ different views on organizational interactions. For example, Kirkman et al. (2009, p. 748) found that: “those with a high power distance orientation tend to behave submissively around managers, avoid disagreements, and believe that bypassing their bosses is insubordination.” Thus, employees high on power distance orientation have developed a sense of how authority figures should be treated and tend to respect management orders and decisions simply because of their origin (Daniels & Greguras, 2014). Research also highlights that employees low on power distance orientation are more comfortable working in environments where a culture of empowerment and support in the workplace is provided (Eylon & Au, 1999).

In previous studies, power distance orientations have mostly served as exogenous variables to explain certain outcomes, but have also been treated as moderators (e.g., Lee, Pillutla, & Law, 2000). For example, Vidyarthi, Anand, and Liden (2014) found that power distance moderates the link between leaders’ emotion perceptions and employees’ job performance. However, none of these studies relate the concept of power distance to workplace creativity or internal idea contests. Thus, studying power distance in relation to organizational innovation – and organization-wide idea contests in particular – may help to reveal the role of employees from lower levels of the organization, who often have no voice in settings where high power distance orientations dominate (Daniels & Greguras, 2014; Taras, Kirkman, & Steel, 2010).

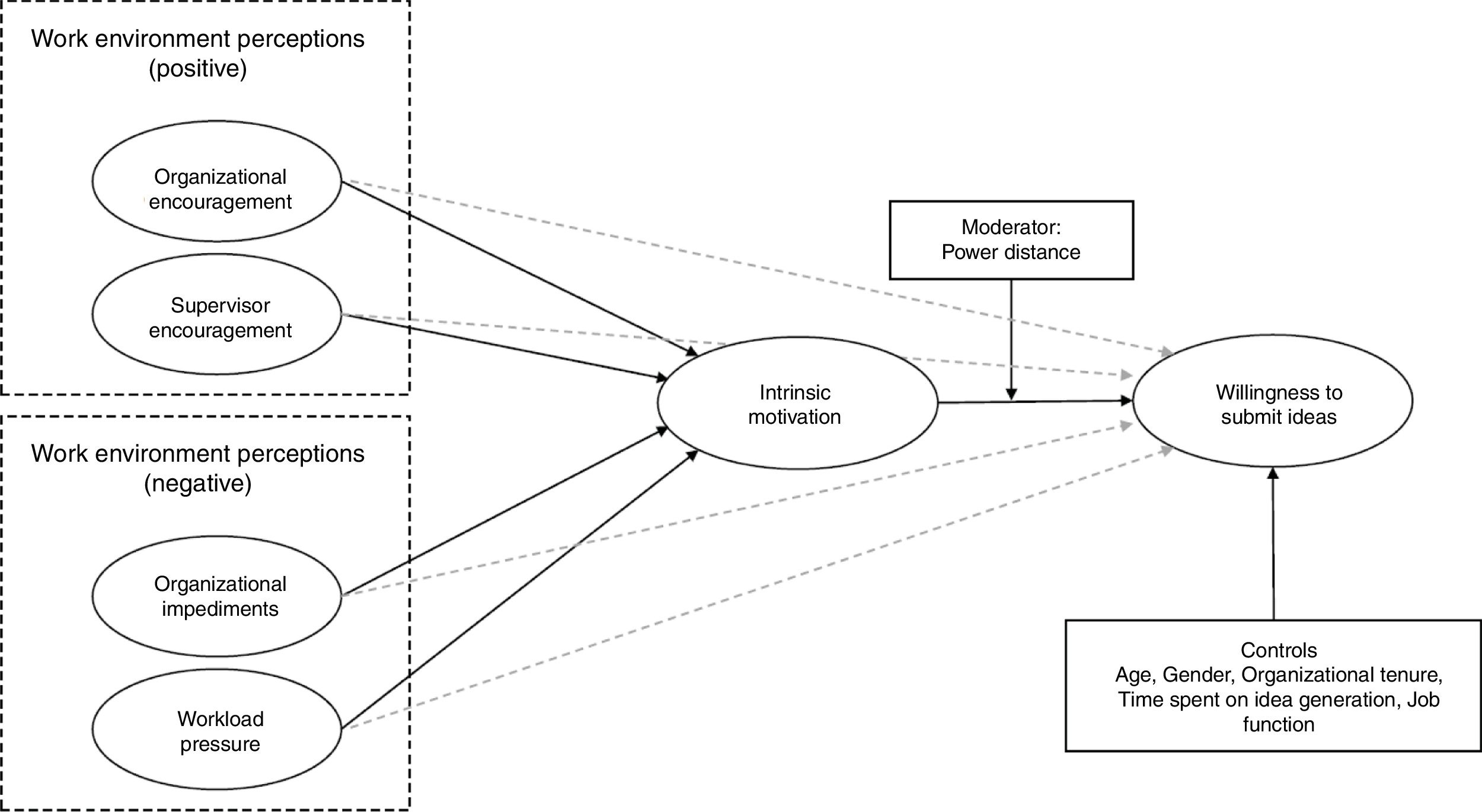

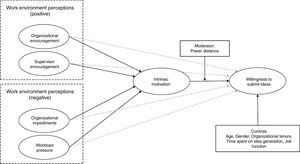

Conceptual model and hypotheses developmentThe proposed conceptual model of our research focuses on (i) both positive and negative work environment perceptions, (ii) individuals’ motivation to participate as important individual attitudes, and finally (iii) their willingness to submit ideas in future firm-internal innovation contests (see Fig. 1). In addition, power distance orientation will serve as a moderator for the path between motivation and willingness to submit ideas.

Regarding positive work environment perceptions, we include organizational encouragement, defined as “an organizational culture that encourages creativity through the fair, constructive judgement of ideas, reward and recognition for creative work, mechanisms for developing new ideas, an active flow of ideas, and a shared vision of what the organization is trying to do” (Amabile, 1997, p. 48) into the model. In addition, we treat supervisory encouragement, defined as “a supervisor who serves as a good work model, sets goals appropriately, supports the work group, values individual contributions, and shows confidence in the workgroup” (Amabile, 1997, p. 48) as a positive work environment perception. Regarding negative work environment perceptions, we first take into account organizational impediments that are defined as “an organizational culture that impedes creativity through internal political problems, harsh criticism of new ideas, destructive internal competition, an avoidance of risk, and an overemphasis on the status quo” (Amabile, 1997, p. 49). Second, workload pressure is defined as “extreme time pressures, unrealistic expectations for productivity, and distractions from creative work” (Amabile, 1997, p. 49) and is also introduced to the model. We chose these perceptions because they reflect the components of CTCIO and they are known to be related to creative behavior (Amabile, 1997). Together, they have the potential to explain why employees at the periphery form motivational cues toward submitting (or not submitting) their ideas to idea contests.

We further integrate (intrinsic) motivation as a potential mediator (e.g., Pellizzoni, Buganza, & Colombo, 2015) because motivations are highlighted as “energizing forces with implications for behavior” (Meyer, Becker, & Vandenberghe, 2004, p. 994). As our final outcome variable, employees’ willingness to submit ideas in the future as a reliable predictor of real participation (Kim, Ferrin, & Rao, 2008; Zhou, 2011) is taken into account as a concrete measure of participation in innovative tasks. We will now explain in detail how work environment perceptions affect motivation as well as the final downstream variable.

Work environment perceptions, employees’ intrinsic motivation, and participationRegarding positive work environment perceptions, organizational encouragement as well as supervisory encouragement are assumed to be important determinants of participation intention in firm-internal executed innovation contests. First, organizational encouragement as a kind of organizational culture encourages, among other things, mechanisms for developing novel ideas, active idea flows, and fair judgements of ideas. Consequently, Eisenberger et al. (1990) confirm that perceived organizational support is related to “innovation on behalf of the organization” (Eisenberger et al., 1990, p. 51) and that “perceived support might be associated with constructive innovation […] without the anticipation of direct reward or personal recognition” (Eisenberger et al., 1990, p. 54). Therefore, organizational encouragement is assumed to be a decisive factor for employees’ intrinsic motivation for participating in idea contests. In a similar vein, and consistent with CTCIO, supervisory support should enable work environment perceptions that are beneficial to employees’ motivation. Supervisory encouragement is interpreted as the support function of direct supervisors, i.e., facilitating open interactions, immediate support, and clarification of goals (Amabile et al., 1996). This support should induce employees to display more intrinsic motivation. Taken together, these suggestions may be captured in the following hypotheses.H1 Employees’ perceived organizational encouragement at their individual work environment is positively related to their motivation for future participation in firm-internal innovation contests. Employees’ perceived supervisory encouragement at their individual work environment is positively related to their motivation for future participation in firm-internal innovation contests.

Regarding negative work environment perceptions, organizational impediments (OI) and workload pressure (WP) are important dimensions, as identified by Amabile et al. (1996). These dimensions are important reasons why employees are limited in their participation in creative and innovative work and might explain hesitant participation in innovation contests. Organizational impediments aim at a culture that impedes innovative behavior through internal politics, criticism, destructive competition, and risk avoidance (cf. Amabile, 1997, p. 49). If these work environment perceptions prevail, employees’ intrinsic motivations are at risk. In addition, employees will reduce their level of organizational attachment. The same holds true for workload pressure. Workload pressure focuses on a negative effect of excessive workload perceived as a means of control of individuals (cf. Amabile et al., 1996, p. 1161). High workload pressure might exhaust employees and eat into their available resources. Therefore, people tend to concentrate on their primary tasks instead of focusing on noncore tasks, such as contributing to innovation contests (cf. Walsh, Yang, Dose, & Hille, 2015). We therefore assume that negative work environment perceptions have negative effects on motivation and propose:H3 Employees’ perceived organizational impediments at their individual work environment are negatively related to their motivation for future participation in firm-internal innovation contests. Employees’ perceived workload pressure at their individual work environment is negatively related to their motivation for future participation in firm-internal innovation contests.

The literature concerning innovative work behavior and idea contests has found intrinsic motivation to be a major ingredient influencing employees’ intention to participate in contests and submit ideas (Dewett, 2007; Zhu et al., 2014). We expect the same positive effect for internal idea contests. When employees are intrinsically motivated, they tend to spend more time on non-core tasks such as searching for ideas and solutions. Thus, the likelihood of finding a suitable solution/idea to submit to the idea contest should increase with high levels of intrinsic motivation. The availability of ideas and solutions, in turn, is a precondition to submitting ideas to the contest. We therefore submit that employees, and peripheral inside innovators in particular, who are high on intrinsic motivation are more likely to participate in idea contests mirrored by their more willing to submit ideas.H5 Employees’ intrinsic motivation for idea contests is positively related to their willingness to submit ideas.

As a peculiarity of this research, we investigate how power distance orientation affects the paths from employees’ intrinsic motivation to their willingness to submit ideas. Studying power distance is important for several reasons. First, power distance orientation is related to perceptions of organizational hierarchy (Schwartz, 1992). As employees’ organizational positions have scarcely been investigated in the context of internal idea contests, studying hierarchy-related issues might bring in fresh perspectives. Second, and even more importantly, the literature distinguishes internal crowdsourcing (and idea contests) for peripheral inside innovators, which take place among all employees, from external crowdsourcing (to an unknown workforce) and classical hierarchy-based innovation approaches. Thus, if power distance explains differences in how work environment perceptions and motivations transform into innovative behavior, further support is delivered for where exactly company-wide idea contests differ from classical hierarchical innovation approaches in R&D labs.

The concept of power distance is conceptualized as a moderator in several studies (e.g., Begley, Lee, Fang, & Li, 2002; Farh et al., 2007; Kirkman et al., 2009; Zagenczyk et al., 2015). For the relationship between the work environment and employees’ attitudes, researchers state that based on the relational model of authority, for less-personalized relationships (or higher power distance orientations), the social exchange theory explanations apply less when compared to smaller social distances (Farh et al., 2007). We assume a similar moderating effect in this study and argue that employees who do not work in R&D departments and have high power distance orientations tend to submissively follow the call for submitting ideas simply because they form feelings that “they have to.” Employees with low power distance orientation might deprioritize idea contests in relation to other tasks and are thus less likely to submit ideas.

In addition, someone high on power distance orientation might see idea contests as a chance to show authority figures – apart from classical hierarchical processes – what s/he is able to deliver. In contrast, given the same level of intrinsic motivation, employees with low power distance orientation who see themselves “at the same level” as supervisors might fear handing in ideas that potentially harm their standing. Hence, this group of employees may be reluctant to submit ideas despite their intrinsic motivation. Thus, we postulate that the relationships between motivation and willingness to submit ideas is affected by individuals’ power distance orientations in a way that the positive relationship is stronger for people high on their individual power distance orientation:H6 The link between employees’ intrinsic motivation and their willingness to submit ideas is moderated by their individual power distance orientation such that employees high on power distance orientation exhibit stronger relationships.

To answer the research questions raised in the introduction, we made use of a survey of employees in an innovation-producing environment. We used a quantitative study design and surveyed employees within a technology and innovation division of a large German DAX30 company in the telecommunications industry. The division is responsible for the group-wide management and development of the product and service portfolio. Thus, coming up with innovation of all kinds is at the core of the division's activity. The division is organized as a subsidiary with its own back office processes including finance, controlling, and human resources—in addition to the core R&D department. Employees on all levels are familiar with modern ideation and product development methods and approaches, and many of them actively use the idea management system in place.

In the questionnaire, we started by requesting answers concerning overall work environment perceptions, that is, organizational encouragement, supervisory encouragement, organizational impediments, and workload pressure. As we could not guarantee that all employees are familiar with idea management systems and idea contests, we further introduced an idea contest scenario to the participants. This scenario involved explaining the concept of software-supported idea generation – with which the majority respondents were already familiar – with screenshots from the system in place (including the company logo and design). In the following, we asked for the assessment of their motivation, and willingness to submit ideas in such firm-internal innovation contests. Finally, we collected the control and demographic variables and asked the participants for answers concerning their individual power distance orientation. We informed respondents that for each completed survey, one Euro was donated to UNICEF.

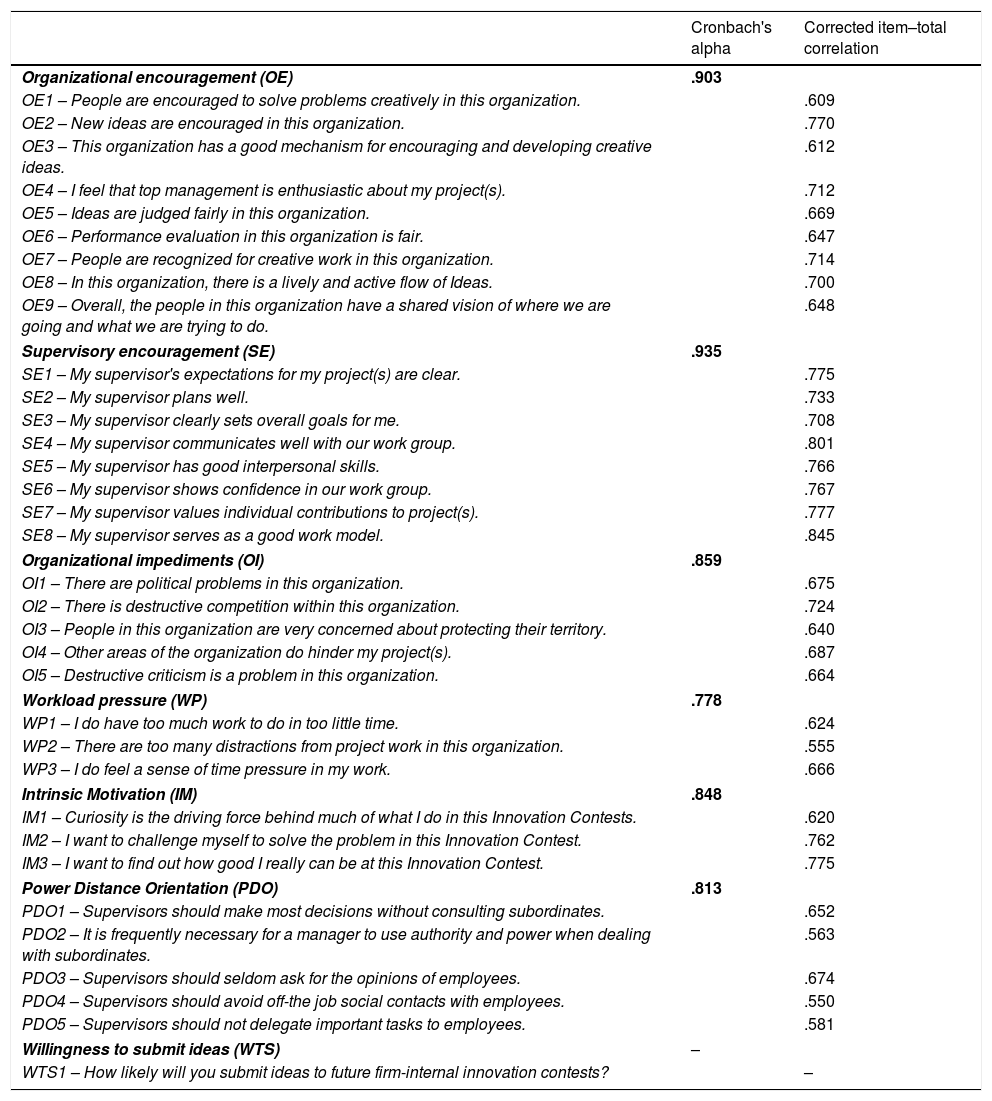

We adapted previously used scales to the context of our study as detailed in the following. The scales for work environment perceptions (Amabile et al., 1996; Amabile, 2010) contain a different number of items for each latent variable: organizational encouragement (9 items), supervisory encouragement (8 items), organizational impediments (5 items), and workload pressure (3 items). For example, regarding organizational encouragement, the respondents assessed diverse statements on how much their organization encourages an innovative work environment and individual creativity. The scale was anchored at 1=“never” and 4=“always or almost always”. While academics usually prefer odd Likert scales, having a four-point scale for these constructs was an explicit wish of the company we worked with. In addition, many of the original studies on CTCIO also made use of four-point scales (e.g., Amabile et al., 1996), which makes our results more comparable to previous work. For intrinsic motivation, we adapted a 7-point Likert scale from existing innovation contest literature (Zheng, Li, & Hou, 2011). One item was: “I want to find out how good I really can be at this Innovation Contest”. To measure employees’ willingness to submit ideas in firm-internal innovation contests, the adapted item reads, “How likely will you submit ideas to future firm-internal innovation contests?” Here, participants could answer on an 11-point, percentage-based Likert scale ranging from “almost no chance” to “as good as guaranteed”, as 11-point scales reflect actual behavior more correctly than other scales (Franke, Keinz, & Klausberger, 2013). Finally, for the measurement of employees’ individual power distance orientation, five items were adapted from Dorfman and Howell (1988) and transferred to the organizational context (also measured on a 7-point scale).

Sample and descriptive statisticsApproximately 750 division members were invited by email to participate in the online survey with one round of reminder emails. After data clearing (e.g., because of missing answers or because the time to complete the survey was very low compared to the average duration of 13.1min), 154 answers could be used for the subsequent steps (response rate: 20%); a number that is assessed as suitable sample size (Anderson & Gerbing, 1984) and that is a “convergent and proper solution” (Iacobucci, 2010, p. 92). Regarding demographics, 64.9% of the respondents were male, and the respondents’ age was 39.1 years on average. The descriptive statistics indicate a broad coverage of employees from the surveyed unit as indicated inter alia by their job function (Marketing & Sales: 15.6%, IT: 14.9%, Finance: 10.4%, Production: 9.1%, R&D: 6.5%, HR: 4.5%, Other: 39.0%). This structure reflects the presence of core internal and peripheral internal innovators. We compared the mean of willingness to submit ideas for those who work in the R&D department with all other departments. Although the mean is slightly higher for R&D people (MR&D=7.70, SD=2.00 vs. Mother=6.80, SD=2.62), this difference is not significant (p>0.10). In addition, we compared those who had prior participation with idea contests (N=46) with those who had no prior participation (N=108) and found that prior participation is related to higher willingness to submit (MPart=8.39, SD=2.07 vs. MNoPart=6.11, SD=2.51).

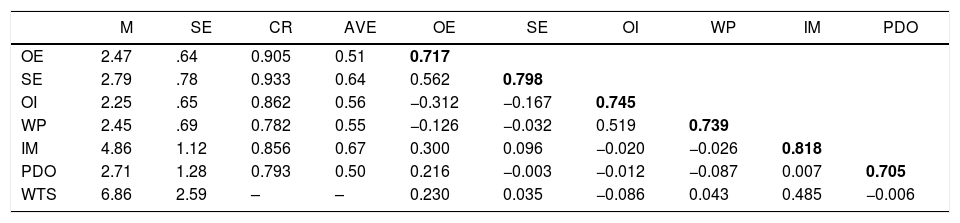

ResultsBefore testing the structural elements of the model, several tests of the measurement model were conducted. In a first step, we controlled for the operationalization quality on the construct level through the analysis of Cronbach's alpha and the corrected item–total correlation for all items. Cronbach's alpha was at least .778 (see Appendix A). Second, at the model level, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis with all latent variables in AMOS 25. All relationships between the latent variables and their associated indicators show significance. In addition, the values for the standardized factor loadings were checked. On the global level, the model fit indicators for the measurement model prove a good fit with the data (χ2/d.f.=1.543, CFI=0.91, RMSEA=0.060, SRMR=0.067). Next, a check for discriminant validity was executed (see Table 1). Here, all AVE values are above 0.5 and all correlations are smaller than the square root of AVE (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Correlations of multi-item scales.

| M | SE | CR | AVE | OE | SE | OI | WP | IM | PDO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OE | 2.47 | .64 | 0.905 | 0.51 | 0.717 | |||||

| SE | 2.79 | .78 | 0.933 | 0.64 | 0.562 | 0.798 | ||||

| OI | 2.25 | .65 | 0.862 | 0.56 | −0.312 | −0.167 | 0.745 | |||

| WP | 2.45 | .69 | 0.782 | 0.55 | −0.126 | −0.032 | 0.519 | 0.739 | ||

| IM | 4.86 | 1.12 | 0.856 | 0.67 | 0.300 | 0.096 | −0.020 | −0.026 | 0.818 | |

| PDO | 2.71 | 1.28 | 0.793 | 0.50 | 0.216 | −0.003 | −0.012 | −0.087 | 0.007 | 0.705 |

| WTS | 6.86 | 2.59 | – | – | 0.230 | 0.035 | −0.086 | 0.043 | 0.485 | −0.006 |

Notes: CR, composite reliability; AVE, average variance extracted; Diagonal: square root of AVE; OE, organizational encouragement; SE, supervisory encouragement; OI, organizational impediments; WP, workload pressure; IM, intrinsic motivation; PDO, power distance orientations; WTS, willingness to submit.

WTS measured on a 11-point scale.

IM and PDO measured on a 7-point scale.

OE, SE, OI, and WP measured on a 4-point scale.

With the remaining items, we also checked for common method bias (CMB). Although we tried to limit the threat of CMB by using different scale anchors for independent and dependent variables, CMB could still be present. Harman's single factor test (in SPSS) indicates that a single factor explains 26.5% of the variance and is less than the threshold of 50%. In addition, we applied the unmeasured common latent factor procedure. Here, no substantial differences in regression weights were observable. Therefore, CMB is not a major issue in this study.

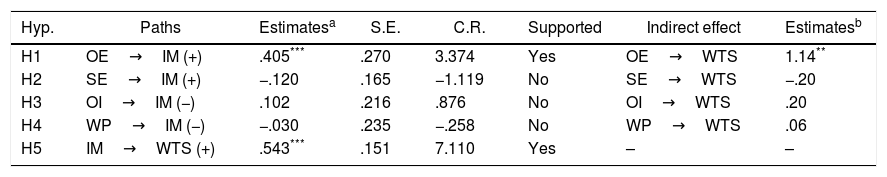

Regarding the relationships between the investigated latent variables, several significant effects could be proven, when structural equation modeling (SEM) with a maximum-likelihood estimator is applied (see Table 2 for all details).1 The model was calculated including four control variables for willingness to submit ideas. Again, the model fit indicators prove a good fit with the data (χ2/d.f.=1.649, CFI=0.91, RMSEA=0.065, SRMR=0.094). First, 11% of the variance in intrinsic motivation is explained by the four independent variables. In the model, the relationship between organizational encouragement and employees’ motivation (H1) could be verified (β=.405, p<0.001). Furthermore, employees’ motivation significantly influences individuals’ willingness to submit ideas (H5, β=.543, p<0.001, R2=.37). However, neither supervisor support (H2) nor organizational impediments (H3) or workload pressure (H4) had a significant effect. Thus, of the first five hypotheses, only H1 (Employees’ perceived organizational encouragement at their individual work environment is positively related to their motivation for future participation in firm-internal innovation contests) and H5(Employees’ intrinsic motivation for idea contests is positively related to their willingness to submit ideas) received support.

Results of SEM.

| Hyp. | Paths | Estimatesa | S.E. | C.R. | Supported | Indirect effect | Estimatesb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | OE→IM (+) | .405*** | .270 | 3.374 | Yes | OE→WTS | 1.14** |

| H2 | SE→IM (+) | −.120 | .165 | −1.119 | No | SE→WTS | −.20 |

| H3 | OI→IM (−) | .102 | .216 | .876 | No | OI→WTS | .20 |

| H4 | WP→IM (−) | −.030 | .235 | −.258 | No | WP→WTS | .06 |

| H5 | IM→WTS (+) | .543*** | .151 | 7.110 | Yes | – | – |

Notes: S.E., standard error; C.R., critical ratio; OE, organizational encouragement; SE, supervisory encouragement; OI, organizational impediments; WP, workload pressure; M, motivation; WTS, willingness to submit ideas.

*p<0.05.

In the same model, we controlled for age, gender and tenure (with an interval measure, 1=‘0 years’, 2=‘1–2 years’, 3=‘3–4 years’, 4=‘5–6 years’, 5=‘7–8’ years, 6=‘9–10’, and 7=‘>10 years’), time spend per week on idea generation (in hours). Of the controls, only time spend had a significant positive relation to willingness to submit ideas (β=.141, p<0.05). In addition, we conducted an ANOVA to test for job functions (with 10 dummy variables), which we did not include as a control. The results indicate that no job function is related to higher willingness to submit ideas.

To test the possibility that work environment perceptions have direct, non-mediated effects on the dependent variable, we calculated an alternative model that included direct as well as indirect paths (χ2/d.f.=1.656, CFI=0.90, RMSEA=0.067, SRMR=0.096). None of the direct paths had a significant effect on willingness to submit ideas. Of the indirect effects (through intrinsic motivation), only the indirect path from organizational encouragement to willingness to submit was significant (tested with 2000 bootstrap samples; b=1.14, p<0.01).

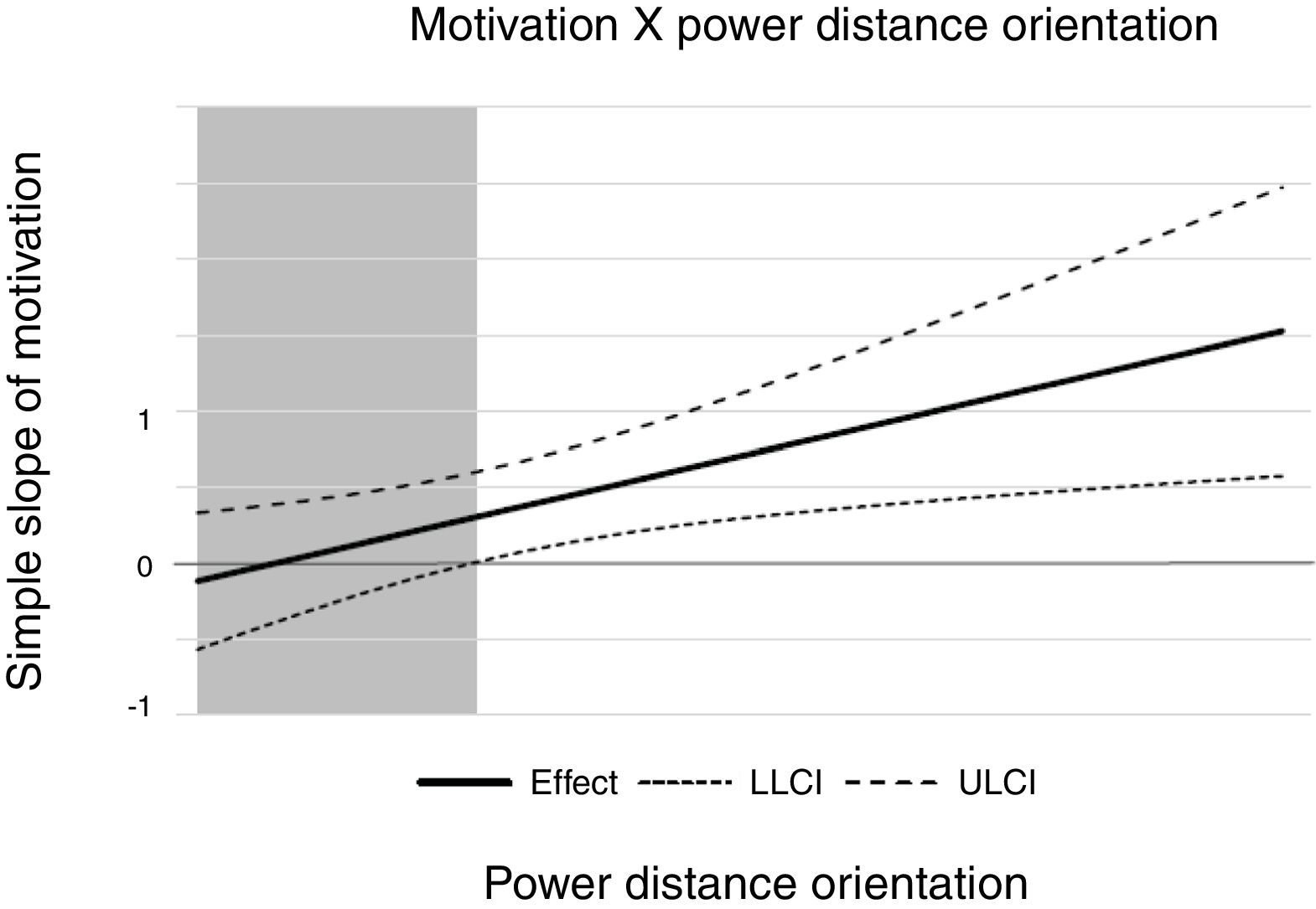

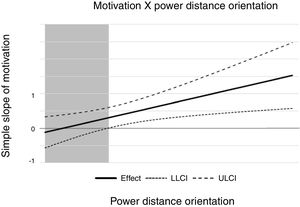

To test for the moderation effect (H6), we did not use SEM. Instead, we used the SPSS Macro PROCESS developed by Hayes (2013). PROCESS uses bootstrapping and delivers confidence intervals for indirect effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) and is able to employ the Johnson-Neyman technique for identifying conditional effects and regions of significance. The authors modeled willingness to submit as an outcome variable, intrinsic motivation as an independent variable, and power distance as a moderator variable (R2=12%). As hypothesized and shown in the structural equation modeling, intrinsic motivation is positively associated with willingness to submit (β=.32, p<0.01), whereas power distance orientation does not show a direct positive effect. As proposed, the interaction effect (intrinsic motivation×power distance orientation) shows a significant positive moderation effect on willingness to submit (β=.24, p<0.05). Thus, we can confirm H6 (The link between employees’ intrinsic motivation and their willingness to submit ideas is moderated by their individual power distance orientation such that employees high on power distance orientation exhibit stronger relationships.)

To further quantify the moderation effect, we visualized the simple slope of intrinsic motivation at levels of the moderator. As Fig. 2 shows, the higher power distance orientations are, the greater is the simple slope for intrinsic motivation on willingness to submit ideas. In addition, the figure shows that the link between intrinsic motivation and willingness to submit ideas is insignificant in the gray-shaded area, which indicates that a certain minimum of intrinsic motivation is necessary with regard to willingness to submit ideas.

Simple slopes.

Notes: The black solid line refers to the conditional effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable at different levels of the moderator (simple slope). The two dashed lines frame the 95% confidence interval of the estimate. Estimates of the simple slope are significant in the non-shaded area.

This study, which explores participation in the context of firm-internal software-based innovation contests, addresses the impact of work environment perceptions as important determinants for the success of such efforts. It also highlights the role of power distance orientation as an important moderator. The findings reveal that only one out of four work environment perceptions has the power to explain employees’ intrinsic motivation. In particular, only organizational encouragement is related to intrinsic motivation, while neither supervisor encouragement nor negative work environment perceptions are. The good news from this result is that negative work environment perceptions do not harm employees’ levels of intrinsic motivation. However, to really increase these levels, top management involvement (organizational encouragement) seems to be more important than supervisor encouragement. In addition, this study revealed that power distance orientations explain differences in how employees transform their intrinsic motivation in their willingness to submit ideas. The following section discusses implications for theory and management for the most important findings.

Implications for theoryThis research used the theoretical lens of the CTCIO to predict future intention to participate in firm-internal ideation. According to the theory, positive work environment perceptions in terms of an organizational and supervisory encouragement should have positive impact on employees’ motivation and on their desired behavior in the context of firm-internal innovation contests. In addition, negative work environment perceptions are predicted to have negative effects. However, while organizational encouragement seems to be a driver of intrinsic motivation, surprisingly, supervisory encouragement has no significant overall effect. This finding is notable, as the wider organizational environment seems to be more important than the more direct supervisor support. While this might come as a surprise from a CTCIO perspective, it resonates well with the goal on internal idea contests: To bypass hierarchical distances (Zaggl et al., 2018). Thus, the role of a direct supervisor is of less importance for the effectiveness of internal idea contests compared to the organizational encouragement.

Furthermore, the two forms of negative work environment perceptions, namely, organizational impediments and workload pressure, do not seem to affect motivation. This finding challenges the basic tenet of the CTCIO and may lend support for the fact that idea contests are mechanisms that bridge traditional constraints. For example, even people with high work load pressure may submit ideas in their spare time, thus, potentially reducing the negative effect inherent in workload pressure. Finally, as expected, intrinsic motivation has a positive effect on willingness to submit ideas.

In addition to the implications concerning the CTCIO, this research has implications for organization theory. In particular, power distance orientation explains why some employees transform their intrinsic motivation into behavior, while others do not. As discussed in the hypotheses development section, people high on power distance orientation might perceive idea contests as a chance to become more visible within the organization without following hierarchical processes (which again explains why perceptions of supervisor encouragement have no effect on motivation). Thus, given the moderating effect of power distance orientation, future research could more often include this concept while studying non-hierarchical work arrangements such as idea contests and internal crowdsourcing. Taken together, this article contributes to the limited body of literature on social-environmental influences within internal idea contests.

Implications for managementOur findings have also direct implications for managers interested in designing and encouraging idea contests. Our first implication pertains to the fact that different effects are prevalent for turning work environment perceptions into intrinsic motivation. First, managers should be aware of the fact that organizational encouragement and supervisory support have different effects. Organizational encouragement, a facet that usually involves top management commitment and presence, has a positive effect on intrinsic motivation. In addition, when supervisor support has no effect, supervisors are well advised to carefully consider when they offer their support—or if they support at all. In times where resources are scarce, direct supervisors might check whether it is possible to run idea contests without larger support. The findings also suggest then when low acceptance of idea contests prevails, it is not caused by negative work environment perceptions. In other words, negative work environment perceptions do not make the overall situation worse. Managers should therefore focus on participation-enhancing aspects rather than potential barriers when setting up idea contests.

All these implications will only live up to their promises, when managers are able to identify employees with high and low power distance orientation. Power distance is a proxy for hierarchy, but not identical to it (Farh et al., 2007). Thus, it may be not enough to separate different forms of encouragements according to organizational levels and departments. Moreover, managers should assess their employees’ power distance orientations, which may even be low for employees close to supervisors in a hierarchical sense, and high for employees on lower levels of the organizational structure. Thus, given the impact of power distance orientations in the context of idea contests, managers may include questions on power distance in future feedback sessions or employee surveys.

Limitations and future researchLike other studies, this work is not free of limitations. First, we focused on employees’ participation intention and willingness to submit contributions in general. In the future, research could differentiate among different behavioral actions within idea contests (e.g., posting, moderating, and reading) (cf. Bateman, Gray, & Butler, 2011). Second, we did not assess employees’ actual behavior. Although the scale we used for willingness to submit ideas is known to correlate highly with actual behavior (Franke et al., 2013), future research could take more objective outcome measures into account. This would also further limit the threat of CMB. Third, with this study, we are unable to predict the quality of ideas and how likely they are to be taken forward to the next steps in the innovation process (Zheng, Xie, Hou, & Li, 2014). Including idea quality in the study would be a necessary next step for future research such that managers may design internal idea contests accordingly (Zaggl et al., 2018). Fifth, concerning workload pressure, we might face a selection bias, as those who have very high levels of workload are likely to refrain from taking surveys. In our case, the mean level of workload pressure is close to the (theoretical) mean of 2.5,2 which indicates moderated levels of workload pressure. Finally, recent advancements in theory call for a combined examination of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations in the context of creativity (Amabile & Pratt, 2016). As we only assessed intrinsic motivation, future studies could replicate our findings including extrinsic motivation.

| Cronbach's alpha | Corrected item–total correlation | |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational encouragement (OE) | .903 | |

| OE1 – People are encouraged to solve problems creatively in this organization. | .609 | |

| OE2 – New ideas are encouraged in this organization. | .770 | |

| OE3 – This organization has a good mechanism for encouraging and developing creative ideas. | .612 | |

| OE4 – I feel that top management is enthusiastic about my project(s). | .712 | |

| OE5 – Ideas are judged fairly in this organization. | .669 | |

| OE6 – Performance evaluation in this organization is fair. | .647 | |

| OE7 – People are recognized for creative work in this organization. | .714 | |

| OE8 – In this organization, there is a lively and active flow of Ideas. | .700 | |

| OE9 – Overall, the people in this organization have a shared vision of where we are going and what we are trying to do. | .648 | |

| Supervisory encouragement (SE) | .935 | |

| SE1 – My supervisor's expectations for my project(s) are clear. | .775 | |

| SE2 – My supervisor plans well. | .733 | |

| SE3 – My supervisor clearly sets overall goals for me. | .708 | |

| SE4 – My supervisor communicates well with our work group. | .801 | |

| SE5 – My supervisor has good interpersonal skills. | .766 | |

| SE6 – My supervisor shows confidence in our work group. | .767 | |

| SE7 – My supervisor values individual contributions to project(s). | .777 | |

| SE8 – My supervisor serves as a good work model. | .845 | |

| Organizational impediments (OI) | .859 | |

| OI1 – There are political problems in this organization. | .675 | |

| OI2 – There is destructive competition within this organization. | .724 | |

| OI3 – People in this organization are very concerned about protecting their territory. | .640 | |

| OI4 – Other areas of the organization do hinder my project(s). | .687 | |

| OI5 – Destructive criticism is a problem in this organization. | .664 | |

| Workload pressure (WP) | .778 | |

| WP1 – I do have too much work to do in too little time. | .624 | |

| WP2 – There are too many distractions from project work in this organization. | .555 | |

| WP3 – I do feel a sense of time pressure in my work. | .666 | |

| Intrinsic Motivation (IM) | .848 | |

| IM1 – Curiosity is the driving force behind much of what I do in this Innovation Contests. | .620 | |

| IM2 – I want to challenge myself to solve the problem in this Innovation Contest. | .762 | |

| IM3 – I want to find out how good I really can be at this Innovation Contest. | .775 | |

| Power Distance Orientation (PDO) | .813 | |

| PDO1 – Supervisors should make most decisions without consulting subordinates. | .652 | |

| PDO2 – It is frequently necessary for a manager to use authority and power when dealing with subordinates. | .563 | |

| PDO3 – Supervisors should seldom ask for the opinions of employees. | .674 | |

| PDO4 – Supervisors should avoid off-the job social contacts with employees. | .550 | |

| PDO5 – Supervisors should not delegate important tasks to employees. | .581 | |

| Willingness to submit ideas (WTS) | – | |

| WTS1 – How likely will you submit ideas to future firm-internal innovation contests? | – | |

A typical concern in the application of structural equation modeling is the use of an inappropriate sample size. Although appropriate sample sizes are heavily discussed among methodologists (some recommend at least n=200, others n=50 [Bagozzi & Yi, 2012]), our sample size may be viewed as small compared to other research articles. As a rule of thumb, a ratio of sample size to estimated parameters should be above 5:1 (Bagozzi and Yi, 2012). Our ratio is only a little above 2:1 (a ratio that has produced well-fitted models in the past), which is why we also ran regressions with averaged parameters. The results remained stable.

Please recall that workload pressure was measured on a 4-point Likert scale. This implies that there is no natural mean in this case.